The Big Picture

Earlier this year, Regal Cinema Union Square in New York City announced it would be shutting down after its parent company declared bankruptcy the previous summer. With 17 screens and 2,000 available seats, the recently renovated three-story, neon-lit multiplex is a vestige of commercial cinema’s glory days.

Up until a few years ago, the theater’s interior design reflected its connection to the heyday of early aughts blockbuster films. Upon entry, visitors were greeted with a larger-than-life still from Spider-Man (2002) featuring the eponymous superhero scaling a skyscraper. As they moved up the escalator on their way to their showing, the hero’s muscular rear would reveal itself to patrons. These days, reports have surfaced that Regal’s own employees have turned to self-financing the theater’s daily operations, taking money out of their own pockets to make sure toilet paper is available on site. Perhaps that Spider–Man photograph was an omen, mirroring the theater’s ideatic cling to sturdier support structures as its faults revealed themselves.

“Our purpose is clear: Screen Slate must purchase and operate Regal Union Square,” wrote Jon Dieringer, founder and editor of the popular New York City film listings website, in response to the shutdown. While he was being facetious, his comment prompted a varied array of interesting responses positing solutions to the closure, as well as equally flippant talk of expropriation on Twitter. Among these, one responder suggested, “The first microcinema multiplex?”

The question embodied a shared feeling among filmgoers today: a fear their favorite medium was disappearing coupled with the idea that if its economic scale were reduced, it might just survive. Mom-and-pop independent theaters began disappearing across the US as increased attention was given to franchise filmmaking and they faced the costly transition to digital projectors around the 2010’s. A decade later, it now appears that large-scale multiplexes are also in danger.

The specter of streaming haunts these communal configurations of moviegoing. With the Covid-19 pandemic challenging conventions behind movie-releases and pushing studios to partner with streaming companies in order to recoup their investments, multiplexes are now in a waning state. Despite AMC’s attempts at reminding audiences of the “magic of the movies” by making a much-parodied Nicole Kidman promo where she proclaims, “Somehow, heartbreak feels good in a place like this,” modern audiences favor the ability to watch anything on one’s own time over congregating for a select viewing. As the multiplex empties, the microcinema remains dogged in its commitment to gathering film lovers for a communal experience.

What are Microcinemas?

Microcinemas are aberrations in the modern filmgoing landscape, best described by film scholar Donna de Ville as “small-scale, do-it-yourself (DIY) exhibition venues.” They ostensibly accommodate all audiences by keeping ticket-costs at a reduced price—anywhere between donation-based entry and $10—yet their proclivity for cinema off the beaten path tends to narrow its audience to die-hard cinephiles.

If your typical marquee promotes a superhero movie, a period drama and an independent film with name actors on any given weekend, the microcinema will most likely advertise an alternative selection of forgotten media, rare arthouse films and curated short-film showcases. This past April, Whammy! in Los Angeles hosted a screening of the director’s cut of Super Mario Bros. (1993), Spectacle Theater in New York committed themselves to showing Filipino auteur Lav Diaz’s 5-hour opus History of Ha (2021) on three separate occasions, and Shapeshifters Cinema in Oakland presented a showcase of Animated Shorts by two filmmakers with a fondness for puppets.

The microcinema exists somewhere between the established arthouse theater catering to outlier consumers and the lonely act of web-surfing for offbeat films. By sticking to a single-screen model and a reduced amount of seating, usually between 30 and 50 spots, these small spaces stay afloat by accommodating the long-tail of modern moviegoing. Theirs is a small, but meticulously designed cinema, usually converting unexpected locales into congregational sites of cinephilia.

Spectacle Theater, to name one example, has operated in the cadaver of a one-time bodega in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, since 2011; the Echo Park Film Center used to host 16mm screenings and eco-friendly film developing workshops in its eponymous LA neighborhood; Caochangdi Workstation has acted as a sanctuary for independent filmmakers in China over the last two decades; and Reg Hartt has been presenting films in his living room under the banner of CineForum since 1992. These microcinemas do not exist for profit’s sake; rather, their existence is bound by their community’s need for outré film and their owners’ willingness to keep putting on a show.

Historically speaking, these sites of alternative viewing in America have only one had thing in common: transience. Yet, since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, many venues were able to hold on to their leases, even investing in remodeling, since they were not held to the same financial standards as their commercial counterparts. “We [were] saved by our own precarity,” said Steve Macfarlane, Department Assistant of Film at The Museum of Modern Art and longtime volunteer at Spectacle Theater, in an interview with The Current.

A Brief History of Alternative Moviegoing

The history of viewing movies in unconventional places dates back to the origins of motion pictures. As part of a greater Vaudevillian tradition capitalizing on common attractions for common people, early cinema either chased spectators to sites of public gathering or rallied them into theaters that were shared with other performing arts. These sites of collective movie-watching engendered a new fanbase for the medium; in turn, giving way to the commonplace movie theater that only shows movies. Though these reign supreme in the public consciousness, as they relate to the microcinema they represent institutions that inspired their makers to replicate their design on a smaller scale. To this effect, many microcinemas today reflect a proto-cinematic willingness to share space and think of themselves less as movie-halls, than neighborhood arts spaces. “The microcinema space is a multi-purpose space,” said Alex Bliss, a member of Life World, an “ephemeral cannery-adjacent event space for performance, cinema, and more” in Gowanus, Brooklyn.

In 1920s Paris, a hungry film audience gave rise to cine-cafés that hosted film club meetings and debates. This tradition remains across Europe, as many bars host regular movie nights, considering the act of moviewatching less of an establishment ritual and more akin to a casual gathering among friends with a like-minded interest. In the wake of World War II, Paris’s stunted film culture returned to its old ways, organizing film societies that hosted even more intense debates on politics and aesthetics; in turn, informing the vanguard of the art-form in theory and practice.

It was around this time that legendary French film archivist Henri Langlois staged simultaneous screenings of Nosferatu (1922) and Sunrise (1927) on different floors of the same establishment while Diary of a Lost Girl (1929) played for spectators sitting in the stairwell. The culture of sharing films-of-merit with other interested parties spread across Europe. It inspired the creation of film societies throughout the continent and eventually America through both hearsay, and the active work of immigrant programmers like the Austrian-born Amos Vogel whose Cinema 16 rallied thousands of members for eclectic showings of rare films in Manhattan during the 1950’s.

Similarly, New American Cinema champion Jonas Mekas toured New York City in search of screens, showing avant-garde films anywhere from 1980s SoHo basements to community theaters. Eventually, these gatherings found homes, which in turn became institutions. As zealousness for movies gave rise to a devoted crowd at places like Anthology Film Archives and Film at Lincoln Center (previously the “Society of Film at Lincoln Center”), ever-stranger outlier spaces continued to form according to their own distinct logics. An alternative to the alternative history of independent arthouses came into being.

A Screen Stretched between Redwoods

On a recent trip to Oakland, I met with the artist known as “tooth” at Café Trieste, a longstanding Italian café in San Francisco’s North Beach. It was one of the few places tooth still liked in San Francisco since it hadn’t really changed since they moved into the city in ‘99. Like many anarcho-punks, tooth dressed in black from head to toe. Their left hand bore the word “LONG” tattooed across their fingers and their right hand was complemented by “WALK.” From their all-black outfit stood out a pin with the phrase “NO FILM” from Kurt Kren’s film of the same name. In 2009, they founded Black Hole Cinematheque and its adjacent film-development lab, citing experimental filmmaker Bruce Baillie as a major inspiration for their curatorial program.

The history of experimenting with cinema in the Bay Area dates back to the origins of the medium itself, when photographer Eadweard Muybridge began working with moving image technology. Though the business of filmmaking migrated to Southern California in the early 1900s, the experimental verve stuck with San Francisco, as figures like Frank Stauffacher, David Sherman, and now tooth, have kept the local film culture alive by staging screenings catering to those looking beyond the offerings of mainstream cinema.

In their resolute quest to keep showing independent films to Bay Area residents for free, tooth has met some of their forebears, like found-footage artist Craig Baldwin and the aforementioned Baillie. Given the smallness of their community, solidarity stretches across generations. Old-timers inspire initiatives carried out by newcomers, who in turn motivate their contemporaries to keep their small, idiosyncratic and local film community alive despite the Bay Area’s shift away from radical countercultural activities. Nowadays, the coastal region is more in tune with the needs of the tech business that has flourished in recent decades, often sidelining anti-corporate creatives despite their tenacious efforts to fight back.

Reminiscing on how they got started, tooth recalled an early encounter with Baillie. “The screening that I saw him at was one where the screen was stretched between two redwoods and we were all sitting out in the ground in the forest, it was really beautiful,” they said. ““His DIY mentality taught me how to put on a screening, how to break things down into particles, saying what do you need for a screening: you need chairs, you need a screen, if I don’t have the money to get a screen, what can I use this instead?”

In the Summer of 1961, Baillie organized a series of outdoor screenings in Canyon, California. Formerly known as Sequoya, the town of Canyon might be one of the last hippie havens in the U.S. Tucked behind Reinhardt Redwood Regional Park about half an hour from Oakland, the sylvan hamlet was founded by squatters in the ‘60s and maintains a proper balance of cabins, creeks and resident tree-huggers to this day. “Our theater began in the backyard of a beautiful lady in Canyon, California, summer, 1961,” reads an early program handout from 1963. “If there is to be new films there must be new theaters, this was the reason for beginning.”

Baillie and his partner-in-crime, fellow experimental filmmaker Chick Strand, were fed up with the fact nobody was showing their movies, and decided to take matters into their own hands by assembling outdoor screenings of films they liked. “The audience was all friends, artists, academics, crazies,” recounts Strand. “It was a party, but very quiet, very joyful.”

After Canyon Cinema reaffirmed the Bay Area still had an appetite for unconventional films, microcinemas began popping up throughout the area. The Co-Op emerged following a series of failed attempts at organizing experimental filmmaking and exhibition practices among local artists in the wake of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s “Art in Cinema Series,” and is considered by many as a catalyzing force behind the area’s sustained engagement with art-films at microcinemas.

An Appetite for Weird

Although people already referred to small movie theaters as microcinemas, the word was never attached to any particular establishment until 1993 when artists David Sherman and Rebecca Barten opened Total Mobile Home microCINEMA on McCoppin Street in San Francisco. The “underground” films they exhibited were actually shown in a basement. The cellar cinema consisted of a mix of wooden chairs and benches that could seat approximately 30 people, a 16mm projector propped up on a stand (usually on top of guests sitting in the last row), and a small screen on the far end of the room. And so, it was in the confines of Sherman and Barten’s short-lived screening room that the term microcinema became associated with similar theaters past, present and future.

The growing punk scene during the ‘90s became fed up with what they deemed an institutional legacy at Canyon Cinema and most places with a history, giving rise to new microcinemas like Sherman and Barten’s but also the more radical No Nothing Cinema! in 1992. As the venue’s name suggests, their showings were characterized by a pervasive performance of effrontery as the venue was not enclosed, but instead spilled over into a basketball courtyard. Their tickets were not priced and their programs catered toward provocation, as epitomized in their “Keep Film Dead” series.

Though tooth’s Black Hole Cinematheque did not start until 2009 when their free showings of avant-garde film in Oakland’s Ghost Ship Warehouse began collecting audience members from across the Bay Area, their commitment to showing rare films in an unusual environment can be seen as an offshoot from the robust microcinema scene of San Francisco in the ‘90s. It was around this time that film collectors like Oddball Film’s Stephen Parr and Craig Baldwin began investing in keeping the Bay Area’s history alive by amassing media that catered to their outlier sensibilities. Both filmmaker-programmers made it their mission to not only preserve legacy media, but also make sure it was seen by recruiting up-and-coming film buffs, having them project 16mm prints, and build short film programs around their collections.

Before Black Hole Cinematheque, tooth had been showing experimental films on patched-together sheets to an average audience of four in the sunroom of an old punk-complex they used to live in. Then, like many artists in the Bay Area during the 2000s, they took up residence in the Ghost Ship Warehouse, a makeshift artist commune that hosted concert venues, work studios, and screening spaces, on top of housing the artists that ran them. “It was a legal gray area that a lot of people in Oakland and the Bay Area have lived in for decades,” said tooth. “A landlord rents a space to you with a general implied idea that it’s maybe not super up-to–code, maybe it’s not legal, but you don’t talk about it.”

When a fire began on the night of December 2, 2016, as a rave was taking place on the same premises, 36 people died in what would become the deadliest fire in the U.S. since 2003’s Station nightclub fire in Rhode Island. “There was a chasm opened up by the loss of people, nobody had the time to grieve and everyone, kind of overnight, knew that the city would weaponize against their tragedy and quickly shut down all the spaces that were similar to mine — artist warehouses or punk-houses,” said tooth. After a years-long effort between local tenant’s rights organizations and warehouse residents to ward off redevelopment, everyone in the warehouse was ordered to be evicted in July 2019.

After an eighth–month stint in New York, tooth flew back to the Bay Area in March 2020 to set up a screening for Light Field, a collectively organized annual showcase of avant-garde film. As the Covid-19 pandemic worsened, they got stuck in Oakland. “I remember thinking, this is where I’m going to wait out the storm, and I don’t think the storm has passed,” said tooth.

This idle time forced tooth to reevaluate the importance of gathering while also working on finishing their own films ahead of a forthcoming retrospective at Rotterdam’s International Film Festival. In September of 2022, tooth set up a GoFundMe establishing a new plan to present film screenings on a seasonal basis while building out the cinematheque’s adjacent film lab so local artists could process their films with people they trusted at a lower cost than sending them out to the Photochem Lab in Los Angeles, the nearest film-processing facility to them.

As we’d chatted over coffee in Café Trieste’s extended hut of outdoor seating, a constant downpour fizzled into a drizzle. We took this as our cue to leave, setting off toward San Francisco’s Mission District, a bustling arts district that once hosted artists working alongside the Chicano Civil Rights Movement but was now home to the profiteers of the Dot-Com boom.

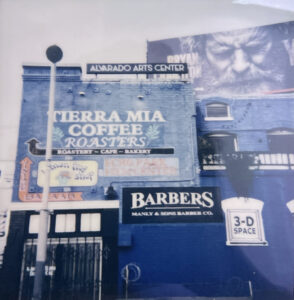

The Mission, as it is commonly called, hosts some of San Francisco’s most revered cinemas among local filmgoers. The Roxie stands out as the oldest continuously operating theater in San Francisco, and Alamo Drafthouse’s New Mission as a more honest account of the dining-experience cinema’s have had to accommodate to survive in more recent times. But it was the strange longstanding gallery space Artists’ Television Access (ATA) that took tooth and me to the neighborhood.

“If you wanna talk about Bay Area microcinemas, ATA is the center of the nerve system,” they said on our walk there. What began as an excuse to party and play around with new technologies during the 1980s had quickly become a landmark destination for a new generation of artists looking to create video-art, a then-maligned extension of filmmaking.

In Craig Baldwin’s Basement

on Valencia Street in San Francisco’s Mission District.

After a knock on the door and a brief wait, we were greeted by Craig Baldwin, 71, the longtime artist-in-residence at ATA whose weekly Saturday showings of experimental films have garnered a reputation for their exciting and haphazard arrangement. His sleeves were rolled up and his hands covered in tape. As he would soon tell us, he was in the midst of planning his program for the months ahead, and each piece of tape represented a jigsaw piece in a morphing puzzle that was more in tune with his inner-logic than any predetermined vision. As Jim Knipfel once described him in The Believer, “Craig Baldwin is the dialectical result of a collision between the Dadaists, the Situationists, the Beats, and the punks. He exists today as a kind of figurehead, a holdover anarchist beatnik from the Bay Area’s pre-tech boom days.”

ATA began in 1984 when San Francisco Art Institute students John Martin and Marshall Weber noticed a growing interest among their peers to work with video technologies coupled with a lack of video-art in galleries at the time. With money from their parents, the two artists formed the Martin/Weber Gallery, a live-in warehouse in the Soma District that acted as an editing bay and screening space for video-artists. The model in play purported artists looking to edit with video technologies would pay to use the facility and could then screen their test-footage before curious audiences as part of the gallery’s selection. On opening night, over six hundred people showed up and the fire department had to be called in. “It was a buoyant mix of drug den bachelor pad, socially conscious editing suite, and gutsy exhibition space that cut a unique swath into the alternative art scene,” recalls an early entry in the organization’s official website.

Now located in The Mission, ATA occupies a Queen Anne style house on the corner of Valencia and 21st St. The main room hosts several rows of black chairs in varying states of decomposition with a floor-to-ceiling white screen pitted before them. This time, the empty space between the first row and the screen was occupied by a table on which Baldwin had laid out miscellaneous documents in the hopes they’d congeal into a workable season program, but it has has been known to host live-bands or lecturers.

“Microcinemas always fail,” blurted out Baldwin as he sipped on stale beer. “It’s about supporting the local film community, microcinemas grow out of us trying to show films to our friends and then those friends invite more friends. Three people have met here and gotten married,” he continued.

Taking a pause from his programming duties, Baldwin proceeded to offer an impromptu tour. The two-story home hosted bedrooms on the top floor, the main viewing room on the ground floor and a basement replete with films in every format imaginable. “It’s a hybrid idea — a store, a lab, people live here!” Baldwin said enthusiastically. Peeking into that basement, one would get the impression Baldwin had kept every single film given to him since he moved in and stuffed it anywhere he could so it might fit into one of his programs when it wasn’t acting as a support beam for the house.

Baldwin pointed at a room stuffed with films and dirt floor, “I need to clean up, somebody’s supposed to move in there.” He then trudged toward the back of the basement, where a series of overlaid ladders acted as the support for a layer of wooden planks holding up hundreds of films stacked on top of each other. Baldwin had been digging niches in ATA’s basement so his underground films could perdure, as though a bunker ration of culture fastening its roots to the changing neighborhood. He then called us back, “Check this out!”

Beneath the stairwell leading into the basement were two projectors and Baldwin began stringing up a film on one. A pair of duct-taped chairs stood across from the small sideways screen; tooth and I took our seats for the spontaneous screening. The mechanical clicks announced the film had begun and a slanted frame of a New Mexico map confirmed Baldwin had managed to run the print titled Sante Fé (No Name) successfully. “A microcinema is a place where you can spill beer,” he cheered.

Beyond the Bay Area

For all its concentrated kookiness, the influence of ATA and the Bay Area scene spilled beyond its coastal premises. The newly inaugurated No Name Cinema, which also hosts a Chess & Jazz Club the first and third Thursday of every month, recently set up shop in a warehouse in Sante Fe, New Mexico.

With community at the forefront of its mission, No Name Cinema’s admission is based on a sliding-scale donation and popcorn is offered for free to all in attendance. The theater itself is made up of four black walls with a couple of in-house film posters hung up, and a hodgepodge of chairs of varying types and conditions that can seat approximately fifty guests. Behind the last row of seats sits an elevated stand complemented by a jumble of wires where projectors can be mounted, creating a sense of intimacy between the audience, the curators, and the machines running the whole show.

“Cinema with a capital C, like art with a capital A,” remarked co-founder Justin Rhody when asked what films No Name Cinema was looking to show in a conversation with New Mexico’s Arts and Culture magazine Pasatiempo. Him and his roommate, co-founder Abigail Smith, hail from Oakland, CA, where they were involved in the same microcinema circuit as Baldwin and tooth. From 2013 to 2018, Rhody organized a public slideshow series of 35mm photo slides titled Vernacular Visions across the Bay Area, always setting up at a different location and making unique soundtracks for each program that he’d share in the form of mixtapes to those in attendance.

This DIY mentality invigorates No Name Cinema, as Rhody, Smith, and collaborator Ben Kujalski design program notes, posters, zines and more for each screening despite the fact that each program is never repeated. The level of commitment carried out by the three collaborators — all of whom tend to the screening space when they’re not at their regular day-jobs — has paid off, as the trio was able to secure a Fulcrum Fund grant last year to stave off low attendance. What started off as an irregular streaming enterprise on Twitch during the pandemic has now found its home among Santa Fe’s art crowd and built a connection with Albuquerque’s Basement Films, a mainstay microcinema founded in 1991. Both cinemas are intent on countering the prevalence of Hollywood films in the state, which has become a growing concern since Netflix and NBCUniversal recently set up studios in New Mexico due to its cheap filming tariffs.

In the neighboring state of Arizona, David Sherman of Total Mobile Home microCINEMA fame has relocated to Bisbee. After his time in the Bay Area, where he also served as president of Canyon Cinema around the turn of the millennium, Sherman now acts as the President of Central School Project, an arts-coop aiding local artists in the creation and promotion of their work. Since old habits die hard, it is also worth noting Sherman and Barten established Tucson’s first microcinema in 2013, Exploded View (also their band’s name). The duo’s work in Arizona has been generative in bolstering new Southwest American artists and bringing unscreened films by trailblazing filmmakers like Shirley Clarke’s portrait of jazz trumpeter Ornette Coleman: Made in America to the area.

From Fringe to Oblivion

Although these newer microcinemas are experiencing success among newfound audiences, the history of microcinemas in America has been one of starts and stops. The “first generation of microcinemas” in the 1990’s, including the likes of Total Mobile Home microCINEMA and Basement Films bubbled out of punk circles responding to the widespread closure of art-house theaters and institutions across the United States and Canada, according to film historian Donna DeVille.

old location in Los Angeles’ Echo Park arts district.

Only a few of them were able to stretch their precarious existence into the new millennium, as commercial cinema reached new heights by building hype around immersive technologies like 3D and novel special effects as seen in high-grossing titles from the era like George Lucas’ critically maligned computer effects extravaganza Star Wars: Episode I — The Phantom Menace.

On top of that, the beginnings of an ongoing effort to commercialize independent cinema through clever marketing campaigns led by studios like Miramax hobbled interest in outlier experimental film. By positioning filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino, Kevin Smith and Paul Thomas Anderson at the forefront of a “new wave” of independent American cinema characterized by dialogue-heavy ruminations on the woes of the absurd American mundane, studios made independent cinema into the new mainstream. Films like Pulp Fiction (1994), Clerks (1994) and Boogie Nights (1997) eschewed formalist innovation; instead, it was their focus on transgressive pockets of Americana or laymen relatability, as told by white cis filmmakers, that captivated moviegoers.

“In the triumph of little films gaining wider acceptance […] the sense of adventure and discovery has been diluted as films of broader appeal attract audiences less interested in the art of film and more interested in the trendiness of art cinema,” argued filmmaker Rebecca Alvin in an essay titled A Night at the Movies: From Art House to “Microcinema” from a 2007 issue of Cineaste. Throughout the early aughts, experimentation in filmmaking and film-showing virtually disappeared across America. A few timeworn microcinemas like Houston’s Aurora Picture Show (housed in a retrofitted church) and Squeaky Wheel in Buffalo, NY, persisted with their regular programming of specialty fare, but the edge of truly independent film appeared to be in freefall throughout the decade.

A Night in Light Industry

On Oct. 18, 2022, I visited Ed Halter and Thomas Beard’s East Williamsburg cinematheque Light Industry as they prepared for a screening of James. N. Kientiz Wilkins’s Public Hearing, a comedic reinterpretation of a small town debate over whether the local Wal-Mart should expand into a Super Wal-Mart. “At the time [2004], the waning of spaces we liked became an impetus to imagine what film culture could be,” said Halter.

Halter programmed and oversaw the New York Underground Film Festival from 1995 to 2005, and met Beard in the lobby of Anthology Film Archives in 2004. A few years later, their joint programming venture kicked off with an inaugural screening of six 16mm short films about utopias titled “This Blazing World.” Light Industry has since occupied two different spaces in Industry City, one in Williamsburg, a period of nomadism archived as the “couchsurfing” screenings on their official website, and a decade in Greenpoint. They recently moved into a renovated loft-space in East Williamsburg after their landlord refused to renew their Greenpoint lease.

“We’ve perfected our cinema space,” said Halter. “There were a lot of mishaps in the early days in Industry City, but it’s informed our refined space now.” The curators’ new space hearkens to the artistic heyday of SoHo that catalyzed the neighborhood’s boutique-ification. With its high-ceilings and minimalist pairing of concrete slabs, blue paneling and hardwood flooring, this sleek iteration of Light Industry sticks to Halter and Beard’s belief that all you really need to show movies is a couple of chairs and a projector.

“Legally, to call yourself a cinema you need fixed seats and a fixed booth,” Halter explained. “We have neither.” Their present set-up is more robust than their previous one, which consisted of fold-out chairs, a cooler full of beers, a 16mm projector, a digital projector, and a screen. Now, their repurposed loft is host to a bar that doubles as an office, and rows of cushioned chairs lined up before a wide screen opposite “The Akerman,” a wooden box concealing an 16mm Elmo projector.

As one of their first screenings in the new space, Halter and Beard are still scrambling ahead of their impending showing of Public Hearing. Their ticket-taker hasn’t arrived, their SquareSpace platform is failing (meaning they’ll only be able to accept cash throughout the night), the film hasn’t been tested, and they’re in the midst of organizing their jumbled collection of film equipment and cables. At the time of my arrival, a large ladder stood before the bar, where a volunteer was being trained to sell beer for the night. Such scenes of scurrying are typical for microcinemas, as they’re often maintained by a small crop of individuals tending to all matters artistic and operational.

While Halter folded the ladder back into hiding and tested the file for the upcoming screening, Beard held back with Halter’s amiable Pit Bull and talked about what drove him to organize the weekly screenings. “On one level, microcinemas are about seeing things you wouldn’t see and the political, social and cultural ramifications that [they] had,” said Beard. “When it comes to creating a cultural common sense, any sense of film history is evolving, being negotiated, and I’m not speaking in a hyperbolic sense, but cinema remembers and we have to constantly re-remember as we interact with film history, which is renegotiated with each screening, series, and event here or anywhere.”

Since they moved to East Williamsburg, Light Industry has shown Bruce Pavlow’s Survival House, a film about a queer group home in 1970s San Francisco; John Abraham’s Report to Mother, a rare Indian film steeped in Marxist politics; and Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville, USA as part of a teach-in and fundraiser to stop the construction of Cop City in the Weelaunee Forest surrounding Atlanta, Georgia. As with most microcinemas, Light Industry’s roots are steeped in the radical politics of self-sufficiency, something they’ve highlighted in their programming when they’re not showing 1940s grindhouse films about women’s prisons or a midday shorts program intended for children collecting an assortment of artistically enlivening content intended for younger audiences. “We have a very open sensibility, featuring diverse outside perspectives,” said Beard.

Ten minutes ahead of the official screening start, the theater began filling up. Attendees moved between dropping their coats on a chair to save their seats and buying Modelos at the bar. A few minutes later Halter and Beard stood up to introduce the film and the cast and crew in attendance. The full house listened attentively and all sense of haphazardness dissipated when the lights went off and black-and-white images consumed the room.

At one point in Public Hearing, a townsperson asks “Why does everybody want to make everything big? Why does everyone want to make a city? We’re a small town — isn’t that the way we like it?” Although the questions in the film are framed around a debate about the construction of a Super WalMart in a suburban town, they could have been posited in relation to microcinemas. Why does everybody want big popcorn flicks? Why does everyone want multimillion dollar films? We’re a small community with a focused interest in film — shouldn’t our sites of gathering feel more communal?

Devotional Cinema

As microcinemas occupy the edge of taste and the economy, the crowd drawn to them is full of familiar faces with similar interests. Sitting up front during the screening of Public Hearing was Jeff Preiss, a member of Light Industry’s board who co-directed the Lower East Side film venue Films Charas and served as a board member for The Collective for Living Cinema during the 1980s. Created in 1973 by a group of film students from the Harpur College Cinema Department, The Collective for Living Cinema was an artist-run cooperative that pushed new voices to engage with forgotten films, while crafting their own contributions to the art-form. “There is a danger in letting one narrative rule a place or scene,” commented Beard. Though small, in size and influence, microcinemas can be considered safe spaces for alternative thinking, always invested in countering the monolithic statements peddled by monopoly-fueled moviemaking.

Located on South 3rd street near Bedford Avenue in Williamsburg, Spectacle Theater has been showing “lost and forgotten” films since its inception in 2011. The microcinema is commonly referred to as “the goth bodega” among its volunteers; the nickname refers to the cinema’s all-black screening room and reputation for showing punk-adjacent media, such as Sarah Minter’s docufiction about Mexico City’s 1980s punk subculture Nadie es Inocente and Matt McDowell’s Sheila and the Brainstem, a bizarro road movie about two newlyweds driving across the United States in search of a magic brainstem.

Despite their smallness, they’ve built a devoted fanbase over the years. With $5 tickets and a B.Y.O.B policy, they differ from nearby small theaters like Nitehawk Cinema and Williamsburg Cinema. In late October, they hosted a sold-out screening of Angela Christleib and Stephen Kijak’s Cinemania, a documentary about five film-obsessed New Yorkers trying to cram as many film showings into their days as possible, typically averaging three to five.

In a Q&A featuring two of the film’s main subjects — Jack Angstreich and Bill Heidbreder — an audience member asked them where they felt film culture was headed given their sustained engagement with moviegoing. Though Angstreich answered pessimistically, saying he felt modern audiences were being cheated out of direct experiences with film due to the transition to digital projection, Heidbreder thought that filmgoing had never felt as familial. “Spaces like this one are maintaining an interest in the art, like in Paris where people walk from cinema to cinema,” remarked Heidbreder.

More remarkable was the fact that the packed theater was full of young faces. Scanning the audience, one would get the impression the seventh art was still a young art and not dying, as so many headlines declared at the height of the pandemic. “It’s fascinating how young our audiences are,” Halter had remarked during my visit to Light Industry. Even at more established venues like the Roxy Cinema in Tribeca, programmer and projectionist Mitchell Glidden noted his audiences feel younger with each screening during a conversation we shared.

Near the Gowanus Canal, Alex Bliss is one of four coordinators involved in running Life World, an artist-run workspace lodged in a converted, two-story warehouse. Bliss is young, has brown curly hair and often snuggles himself in his black jacket like a turtle.

A filmmaker by day, Bliss is in charge of coordinating all of the venue’s cinema events: This involves the nitty-gritty of setting up chairs before screenings, but also ripping movies, testing whether they work, and on the rare occasion, bringing out a ladder to balance a 16mm projector. A relative newcomer to New York’s DIY-art-scene, Life World is still stabilizing its event schedule, hosting free showings of cult films, partnering with new artists to showcase their work, staging avant-garde theater performances, and irregularly broadcasting a public access comedy show.

Early in December last year, Life World presented a series of short films under the title “Films by Very Young People.” The program consisted of short works made by filmmakers working with modest budgets under the age of 25. Having arrived a bit early, I assisted Bliss with the set-up, moving mismatched sofas around the venue to accommodate the growing RSVP list. Tucked behind a table full of cables, Bliss was in charge of the projection. He clicked play and leaned back, as a room brimming with novice filmmakers applauded each other’s work. If the sentiment that movies were on the out among the younger generation was in vogue, being in that room said otherwise.

Against Hollywood

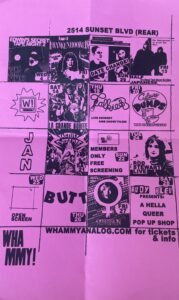

Hidden behind a parking lot in Los Angeles’ Echo Park district is Whammy!, a VHS shop that doubles as a microcinema. It is run by Erik Varho and Jessica Gonzalez, a couple of VHS collectors who decided to open a storefront after their online shop grew exponentially during the pandemic. Having inherited seats from the now-defunct Echo Park Film Center, Whammy! invites local film programmers to host screenings in the back of their shop. Though Los Angeles may be thought of as the capital of the commercial movie market, the proven success of these entrepreneurs seems to signal there also exists a counter economy in opposition to Hollywood.

Los Angeles has no shortage of great programming, as it houses the American Cinematheque alongside independent theaters like Quentin Tarantino’s New Beverly Cinema and Braindead, as well as smaller spaces such as Acropolis and 2220 Arts. Yet, given the city’s ties to big names and big talents, its repertory theaters seem to lean into canonical works; in turn, capitalizing on that which is known, or is nominally cool, to pack the house. Each theater is its own brand, fending to sustain itself in a saturated market.

“We’re looking to fill the gap of accessibility to screens in LA,” said Varho. “There’s still some gatekeeping around who is worthy of programming.” In the back end of the couple’s store, it’s hard to feel any distance from the people running the show. The polka-dot décor is fun and inviting. Accompanied by a popcorn stand and the smallness of the whole affair, the sense that anyone can mount a screen, pile some chairs, and present a movie feels plausible. “It’s accessibility, the fact that it’s a smaller room pressurizes a community-aspect to the screenings,” remarked Gonzales.

In the past, Whammy! has hosted everything from screenings of cheesy forgotten VHS flicks to works of expanded cinema, where people had to dodge projectors as they walked through the space, according to its owners. As a site that can suit the needs of avant-garde artists and idiosyncratic individuals who want to share their singular passions, Whammy! embodies the microcinema movement’s mission: that people can still be united by weird and interesting things. As Gonzales wistfully stated, “A lot of people running microcinemas think there should be one in every neighborhood.”

In an age of intense serialization at the movies, Whammy! and microcinemas across America offer a window into another world. In the crammed comfort of Whammy!’s timeworn chairs staring at a tiny screen, it’s a bit harder for you to lose yourself in a larger-than-life picture. But, the immediate surroundings, like neighborly popcorn crunches and background shuffling, feel more alive. The multiplex is emptying out and its patrons have turned to smaller, more intimate experiences.

Correction: This article previously misstated the relationship between Thomas Beard and Quinn the Pit Bull at Light Industry; Quinn is Ed Halter’s friendly companion.

Special thanks to Julia Mejia, Ted Conover and Robert Boynton at New York University, Steve Macfarlane, Troy Swain, Ed Halter and Thomas Beard at Light Industry, tooth, Craig Baldwin at Artists’ Television Access, Erik Varho and Jessica Gonzalez at Whammy! Analog, Courtney Muller, Catherine Benge, the constant support of my peers throughout these last two semesters, and my parents for ceding the little time we get to spend together during winter breaks so I could travel and report.