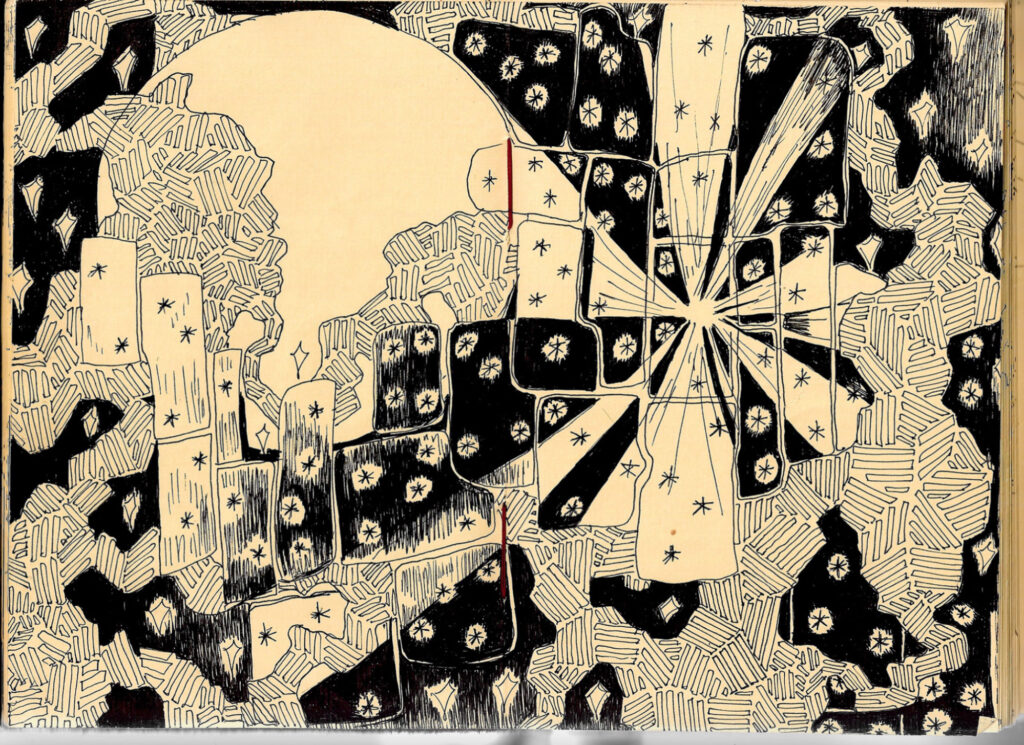

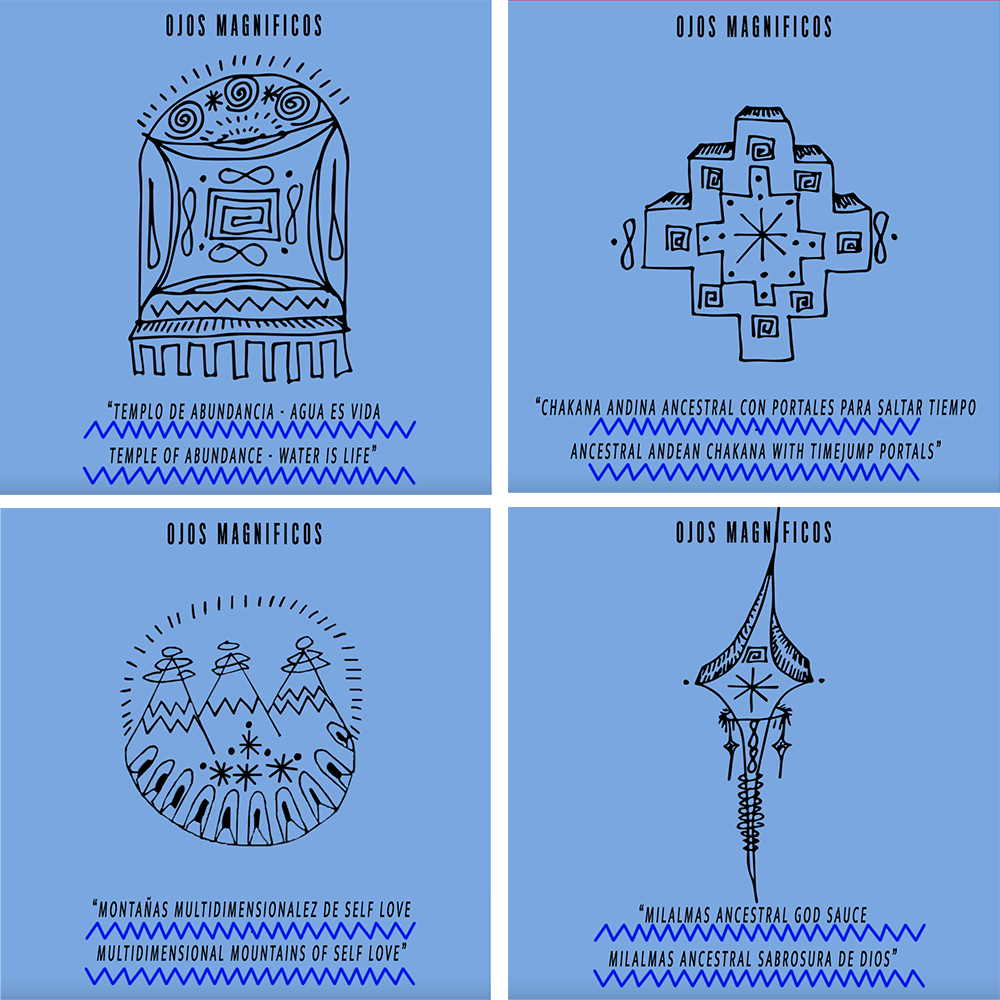

The pages of Pili Ojos Magnificos’ notebooks are filled with abstract shapes, jarring colors and jagged lines — daring depictions of another dimension. Sitting in their bedroom, gesturing toward their forehead and opening a metaphorical third eye with their fingers, Pili describes the process by which they channel their tattoo designs from the cosmos.

“I feel like I’m a funnel,” the Baltimore-based tattoo artist says, as their fingers trace a cone-like shape above their head, nearly touching near the crown and widening as they ascend. “Someone comes to me and they’re like, ‘I have this image, I want this,’ so I translate it into my style. I listen to their story — I listen for what medicine they need.”

Pili is a tattoo artist, but the label doesn’t begin to encompass the work they do. Alongside a number of other artistic endeavors, Pili has taken the traditional American tattoo experience and flipped it on its head. They see tattooing as a ritual, a return to the Indigenous or familial roots of their clients. They want their customers to walk away not just with new ink, but also with a new sense of self-confidence, rooted in their ancestry and background.

The self-taught artist’s creative process begins long before they actually tattoo, gaining momentum during a nearly hourlong, “therapy-based” consultation over Zoom. Pili referred to these exchanges as “vetting calls.”

During the calls, the artist and prospective client “exchange energy” and discuss their respective ancestral lineages. Pili wants to know what their clients are going through and how that’s informed by their background — something they said leads to clients sharing heavy, intimate facts about their lives.

This sentiment translates to the aesthetics of Pili’s tattoos, too. Non-personalized designs are not enough for the artist. During the tattoo ritual, they aim to open what they call a “blood portal,” a point of passage to past generations, and an opportunity to provide an offering to this distant, oft-forgotten family. Seeing into that portal allows Pili to create a design that speaks to the client’s wants, needs and ancestral trauma. They then explain the design’s meaning to the client and make any necessary adjustments.

“Where are you at? Who are your people? What do you remember?” Pili asks, chronicling the questions they ask their clients during the pre-tattoo exchange. “It’s so important to understand the emotional state. If I only focused on designs, I would start to forget my clients.”

Pili’s practice is multi-dimensional, informed by their Colombian ancestry, Miami upbringing and New York City schooling. The young, self-taught, fairly new tattoo artist is forging their own path in the industry — but not alone. Their tattoo ritual, which focuses on consensual and trauma-informed care, is part of a larger movement in the tattoo industry, one that centers the client’s and artist’s emotional wants and needs.

The tattoo experience is moving away from the kind of transactional exchange that one typically associates with modern tattooing — a quick, stenciled design, a gesture to the ATM in the corner and a swift push out the door. Pili, at the center of an innovative Baltimore circle, is leading the way in including the client in the process, from before the tattoo is designed to days after it is completed, often establishing long-term relationships along the way.

A growing group of artists have also come to terms with an often-unacknowledged emotional burden taken on by tattoo artists, and are equipping themselves with the tools they need to protect themselves, along with their clients. As a result, the level of care they offer goes far beyond an ink-to-skin exchange. Clients seek this new level of care, many having sought the service in the traditional space first before turning to the alternative.

But within an industry that’s steeped with history — from prohibitions to pin-up girls, over hundreds of years — many traditionally trained artists long for the heritage that, to some extent, is being left behind by new generations of tattooers. Others are grappling with the reality that new shops attract a new clientele, diversifying an already burgeoning industry into something they have trouble recognizing. Some of these artists question whether new artists teaching themselves how to tattoo might compromise a staunch connection to tattooing’s cultural background.

Many new tattooers like Pili, in part by choice and in part due to the impacts of COVID-19, forgo traditional tattooing apprenticeships and teach themselves instead.

“I’ve had a lot of backlash because I’m self-taught, and I think that it’s very colonial and gatekeeping,” Pili said. “We should not shame people who feel inclined to prick their skin with ink — like, that’s so human. It’s very natural for people to experiment with those things … Being self-taught is a grind that people really underestimate.”

A Trauma-Informed World

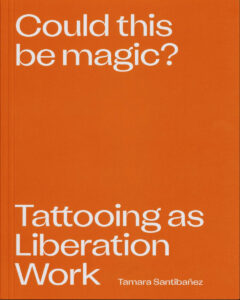

An artist based in Brooklyn, New York named Tamara Santibañez is at the forefront of the movement toward trauma-informed tattoo. A queer, transgender, multi-medium artist, Santibañez works out of a collective studio that they share with a handful of other tattooers. With a long career of tattooing behind them, and experience constructing oral histories of the industry, they know what the traditional tattoo world looks like — and they’re sympathetic to its faults.

“I think the big reason that tattoo artists were so notoriously bossy or authoritarian in their spaces was developed as a tactic to resist real danger,” they said. “Tattoo shops used to be places where people were at a higher risk of being robbed, or of violence, or of people behaving really badly.”

Several years ago, Santibañez worked closely with the Women’s Prison Association, which provides recovery services to women who have been impacted by the criminal justice system. It also offers a free, trauma-informed tattoo cover-up service to imprisoned women with unwanted tattoos. The organization’s website features the testimony of a woman who was branded with her abuser’s name. Over 85% of imprisoned women have been sexually assaulted, and this is just one example that serves as evidence of the impact that unwanted ink can have on one’s mental health. After tattooing women with the Women’s Prison Association, Santibañez knew something had to be done.

“In that instance, it was kind of an immediate need — people had been tattooed in a way that was violent,” Santibañez said. “How could we tattoo them again in a way that would empower them and remind them, every step of the way, that they were in control, and it was toward their own agency and empowerment?”

Santibañez’s work with the Women’s Prison Association inspired them to create a free, point-by-point guide for tattooers wanting to incorporate trauma-informed care into their own practice. Working with artist K. Lenore Siner, who was featured on the reality television show “Ink Master,” Santibañez developed their Client Bill of Rights. The downloadable resource covers everything from the importance of maintaining a sanitary tattoo environment, to promoting open communication between artist and client, to providing accommodations for people with disabilities.

Published in 2021, “Tattooing as Liberation Work” is perhaps Santibañez’s most impactful mark on the tattoo industry. Described on the artist’s website as “part manifesto, part love letter, part workbook,” their bright orange pamphlet covers straightforward concepts like consent and how the physical space of a tattoo shop is arranged. It goes further, though, delving into more complicated conversations about transformative justice and intergenerational trauma — all of which, Santibañez argues, present themselves in the tattoo space. And the artist has made trauma-informed care profitable too, offering online workshops for $45 and one-on-one consultations for $120, both services catered toward tattoo artists hoping to transform their practice.

Santibañez admits there are issues with using the term “trauma-informed,” though, noting that trauma and its treatment can mean many different things for different people. Because of this, they said they centered the book, and several of its chapters — which include “An Intersectional Theory of Client Care” and “Modeling Community Accountability in a Shop”

— on liberation and justice, rather than trauma. Their goal is to empower customers and artists to implement the practice, not bind them to a strict set of guidelines that may feel overwhelming.

To create a comprehensive guide to incorporating trauma awareness in the tattoo world, Santibañez thought about those who deal intimately with clients’ bodies across other industries — think sex workers, yoga teachers and acupuncturists — and interviewed them.

Their community outreach doesn’t end there, though. At the beginning of the pandemic, they also hosted a discussion group with other tattoo artists, aiming to create an avenue of support for those whose work was altered significantly by the advent of COVID-19.

“We spoke about tattoo ritual, magic, working to divest from capital, utopian visions of tattoo futures, long-distance tattoo science fiction fantasies — topics that felt miles away from what the mainstream tattoo industry was attuned to,” Santibañez wrote in their book’s introduction.

Santibañez represents a growing subsection of the tattoo industry that has adopted trauma-informed care, but the practice has spread across the personal services industry as a whole.

Trauma-informed or trauma-aware practitioners, from tattooers to social workers to — believe it or not — gardeners, acknowledge the near-constant presence of trauma in their clients’ daily lives. They recognize their ability to influence people’s responses to trauma, and the potential for their treatment to be both healing and re-traumatizing. Incorporating a trauma-informed approach looks different in every industry, but can be as simple as asking for consent before touching someone, or offering them a glass of water during a tense moment.

“We have to always be mindful that the person across from us might be impacted by trauma, and that there are many things that we can do unintentionally that can trigger and re-traumatize them,” said James Rodriguez, a longtime social worker who is the senior director of clinical initiatives at New York University’s McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research. “That could be anything — it could be the tone of my voice that reminds someone of an abusive parent, or the smell of my cologne that reminds them of an abuser.”

The idea of managing trauma isn’t a new phenomenon, and encompasses an area of research transformed by the 1995 Adverse Childhood Experiences study, Rodriguez said. Researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente studied the prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, which include abuse, neglect, domestic violence, economic stress and exposure to a family member who struggles with addiction.

In the research, which altered the field of psychology, they found that more than two-thirds of the population was affected by at least one ACE — and that these traumatic experiences led to toxic stress and, therefore, a host of negative physical and mental health outcomes. After the study illuminated the prevalence of trauma in the general population, principles of trauma-informed care gained popularity, though mostly within a clinical, psychological setting.

Just after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Rodriguez moved to New York City, and immediately got involved in administering trauma treatments for children who had been affected by the tragedy. He said that 9/11, as was the case for other mass tragedies, gave a boost to the newfound focus on trauma-informed treatment within health care, and made more people aware of the prevalence and impact of traumatic experiences.

Inching closer and closer to the mainstream, this wave of trauma-informed care doesn’t seem to be slowing down. Rodriguez said that widespread issues like COVID-19 and heightened political divisions in the United States have created an increased demand for therapeutic services, and an overall need for empathy and trauma-informed care.

“If you were to ask me what a trauma-informed world would look like, it would look a lot more compassionate,” Rodriguez said. “It would look like people are more concerned about each other’s safety.”

In his work with NYU’s McSilver Institute, Rodriguez offers training and technical assistance to both mental health clinicians and people working across a number of other industries who want to incorporate trauma-informed care in their workplace. Rodriguez said that, to him, incorporating trauma-informed care within the tattoo industry makes a lot of sense, and even has the potential to increase practitioners’ profits — whether that’s the artist’s intention or not.

“It involves being close to people, it involves injecting people, it involves pain for people, so there’s all these factors that are involved and can potentially be re-traumatizing to folks,” Rodriguez said. “For the tattoo industry, I can understand why being careful, being gentle, being mindful of how you’re talking to folks — but also your proximity to folks — all of those kinds of things can make a difference.”

Though fairly new, Santibañez’s book, which focuses on many of these considerations, has circulated within Brooklyn, and to artists across the country. Artists who are aware of trauma-informed tattooing know who Santibañez is, and often have a copy of their book sitting on a table in their studio space.

Preparing for a day of tattooing, Brooklyn artist Stephanie Tamez was sketching designs alongside her wife, tattooer Virginia Elwood. Tamez said Santibañez’s book has informed her practice considerably, calling it “groundbreaking.”

Elwood agreed, saying that her work, too, has shifted significantly over the last couple of decades — informed both by her own intuition about customers’ needs, and by Santibañez’s resources. She said that while 20 years ago she would have just rolled up a client’s sleeve herself when she needed access to the area, now she asks for consent — she ensures the client is comfortable by asking if they’d rather roll the sleeve up themselves.

Many clients appreciate the new level of care practitioners like Elwood provide too — whether they’re directly influenced by Santibañez or not — and many actively seek it out. One such client is Terra Marzano, a private practice social worker from Oregon. Marzano knew that whoever she paid to do her next tattoo had to express a level of inclusivity and sensitivity she rarely saw advertised by traditional shops.

Marzano had previously had positive experiences at traditional American tattoo shops. She has a small, impulsive tattoo on her foot, but wanted more for her next addition — a large piece which was to span her sternum and cross under each of her breasts. Marzano, 48, got the large tattoo two years ago, and said she was nervous about the vulnerability it would require, at least in part due to her age. Older than the models that most tattooers feature on their websites or social media accounts, she made a conscious effort to find an artist that showcased tattoos on different body types, and on people from marginalized communities. This indicated to Marzano that the artist was “sensitive to different human experiences.”

She said that when she arrived at Desert Sun Collective, a studio in Portland, she was greeted at the door by her tattooer, Mia Celeste, and welcomed in.

“Get stabbed with a needle — enjoyable??” the collective’s website reads. “YES! With a chill environment, mellow music, and artists who care about your well-being, you’re sure to walk out of the studio with a lovely piece of art and memories of a good time!”

The employees at Desert Sun made a conscious effort to make her feel comfortable, but not in a “rehearsed” or “sterile” way, she explained. Although there were male tattooers present — one of whom came over to look at the tattoo’s progress midway through — Marzano recalled that she did not feel self-conscious at all.

“I was on a table with my top exposed, and they were just really patient with me and patient with everybody in the space,” Marzano said. “In very subtle ways, part of what I experienced is real, genuine openness: ‘We have a lot of time, there is no reason to rush. If you want to take a break, let’s take a break. If you’re not sure, let’s take a break anyway.’”

Marzano’s preference for trauma-informed care does not just present itself in tattooing — she has developed an appreciation for the practice throughout her time as a therapist. She noted the financial burden and time commitment often required to implement trauma-informed care. Whether the shift requires longer appointment times or renovations to a clinical space, Marzano emphasized the importance of sacrificing these disruptions for an elevated level of care.

“There’s a wide range of artists available, and thinking about who I would support felt important to me,” Marzano said. “It matters who gets the bigger platforms, and whose work is elevated, so it felt for me like this was an opportunity to find somebody — it’s sort of like voting with your dollars.”

If Jay-Z Died Tomorrow

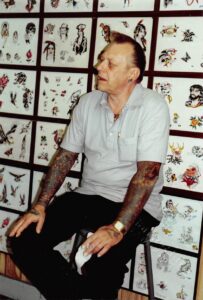

The appeal of the trauma-informed model isn’t immediately clear to some old-school tattoo artists. Many haven’t even heard of the phenomenon. Maintaining successful practices themselves, they have stuck to the ways in which they always tattooed, and have kept their seasoned clients while also gaining new, young, diverse customers. However, some take issue with the new wave of budding tattooers, lamenting the loss of traditional training, old-school values and the history of the art form.

Tucked away inside a red-doored apartment building on First Avenue, in the heart of New York City’s Lower East Side, lies Fine Line Tattoo — one of the city’s oldest tattoo shops. Now owned and operated by Mehai Bakaty, trained by his late father, Mike, Fine Line found its start in the younger Bakaty’s childhood home, at a time when tattooing was illegal in New York.

New York City’s tattoo ban was instituted in 1961 and lasted nearly 40 years. The city claimed the prohibition was due to an outbreak of hepatitis, but the true reason behind the ban is hotly contested. Shortly before it was finally lifted, Mike and Mehai signed a lease on a storefront for Fine Line, and Mehai now operates out of a studio apartment behind the original space

“For allowance money, I would clean the tattoo shop, stuff like that,” he said of the makeshift studio his father had built inside their Lower East Side loft. “I’d get home from school, he’d be working, and I’d take a nap to the sound of the tattoo machine. The first tattoo design I ever drew, I think I was about 10 years old. I just kind of plastered a couple of things together. He ended up putting that design on the wall, and I thought, ‘Oh man, that is fucking cool.’”

Because of his family ties to tattooing, Bakaty’s apprenticeship didn’t quite match the blueprint. He started informally at a much younger age than most, and didn’t have to seek out a shop — he had one built in. But he represents a generation of artists who had to learn much of the process manually, with exclusively word-of-mouth knowledge and limited equipment. Bakaty said that there were only about two tattoo supply houses in the entire country at the time — now, he said, there are hundreds. Because tattoo equipment was so hard to find, it was accepted that artists would make their own needles, ink and machinery.

“Dad would go and buy packs of bicycle spokes, and we’d sit there and bend the needle bars by the loose needles and tack them together with solder,” Bakaty said. “You know, buy the powder pigment for inks, and mix them all together. That’s a traditional apprenticeship.”

Though an apprenticeship traditionally lasts five to six years, give or take, Bakaty said he’s noticed that changing. Now, largely because information on how to tattoo is easily accessible online — TikTok, YouTube and other platforms host free, instructional videos and showcase people documenting their learning experiences — and people have the ability to order nearly anything you’d need to open a tattoo shop off of Amazon, anyone can learn to tattoo.

Though artists like Pili Ojos Magnificos find that to be liberating, a sign of inclusivity, Bakaty thinks some things can’t be taught online.

“Painters in the Renaissance used to have to know how to make their own brushes, they used to have to know how to mix their own pigments,” Bakaty said. “Now you can go to the art supply store and buy everything pre-made, pre-packaged. You don’t even have to know how to cook to survive anymore. You just get Blue Ribbon or whatever. You know, follow the instructions. And that’s it. We live in a very well-packaged society these days.”

Bakaty said he frequently comes across young artists who aren’t even aware that in the very recent past, the craft was banned in the city they’re working out of. Many artists also no longer have mentors to educate them on making their own needles and ink, and don’t learn about the figures who, as he said, “carried the craft through the years.”

“The heroes, the tattoo gods, are falling by the wayside, and that’s a shame,” Bakaty said. “It’s just sad. It’s sad to see, having grown up like that. It’s like if Jay-Z died tomorrow and nobody knew who he was in 10 years, or cared. Which is probably what’s gonna happen.”

Bakaty is in agreement with Pili and Santibañez on at least one front, though: the political power of tattooing. He takes issue with the sentiment that the craft’s power to liberate is new, though, tracing this capacity back thousands of years. He said that tattooing has always been tied to trauma and selfhood, and expressed reluctant gratitude that the art form’s politics have come back into conversation. He’s just less inclined to talk about trauma explicitly, unless the client goes there themselves.

“I think very much that tattooing is often desired by people going through severe trauma, or just coming out of some trauma, and they need that thing to anchor them back in their own body to take control,” he said. “I’m not trying to demean anybody’s work, but to me, it kind of goes without saying, and it’s almost a little gauche to go there. In my experience, a lot of the time people are getting cathartic tattooing, they don’t necessarily want to talk about it.”

Nearly every day, Bakaty experiences the same emotional burden discussed in Santibañez’s book. He said that, often, clients will “unload” their traumatic experiences onto him. His father used to describe being a tattoo artist as “somewhere between being a therapist, a prostitute and a shaman,” alluding to the many, sometimes-unnamed hats that a tattooer wears while a client is in the chair. But, as he says, taking on that load is “not necessarily what my job is.”

“I’m not a therapist. I am not a clinical technician. I’m an artist. I’m a tattooist,” he said. “There is a psychology to it. But to go out of the way to suggest that that’s the service you’re offering? You’re drawing on people. Let’s keep that clear.”

Bakaty still knows artists who don’t care to listen to their clients — artists who will put headphones in while they work, closing themselves off to the interaction altogether — but he admits that the industry has changed drastically, from “rough and tumble” to “elevated” and “artistically minded.” He said he sees some of this shift as a business strategy, an excuse to charge more for what he sees as largely the same service.

Though tattoo pricing varies significantly, often depending on an array of factors — including time spent drawing, the complexity and size of the tattoo, the colors used and the time spent on the table — old-school artists like Bakaty have taken issue with the fact that newer artists may be charging more for their tattoos, which are given in a boutique space, and offered alongside a host of additional services.

Prices aren’t typically disclosed until a client discusses the design and expectations with the artist, and generally don’t account for an added tip. Standard minimum rates fall around $100-120, but these can increase significantly if a therapy-like discussion or more ritualistic practice is included.

Although Bakaty takes issue with many younger artists who, because of their self-taught status, have sacrificed much of the traditional tattooing knowledge, there is a significant portion of the tattooing community that has experienced both sides of the industry — the old-school, traditional apprenticeship model, and one of their own making. They’ve learned within the intense, every-man-for-himself craft, but have actively decided not to impart that model to their protégés.

I Had to Fight

Newly in labor, soon to give birth to her first child, Kristel Oreto pulled out a pen, scrawled out a quick message, and stuck it to the door of the tattoo shop she was working in — a notice to her colleagues and clients that she was unavailable, on her way to the hospital. Oreto, then just 18 years old, was tattooing clients until that very day, and returned to the shop less than a week later. As a young woman trying to make her way in a notoriously unforgiving industry, she felt as if a day off could compromise her career.

Now in her late 30s, the artist said she “sold her soul to tattooing.”. When she was 15, she got her first tattoo and sat in on another friend’s appointment. During her friend’s session, the shop’s owner was out for the day, so the tattooer let her assist with the process. He then encouraged her to attend a convention taking place in Florida two weeks later, showcasing only the work of female tattoo artists. By the time she was 18, Oreto was tattooing full time.

“I didn’t know that women could tattoo,” she said. “At this point, there’s less than 500 lady tattooers in the world. I decide I’m gonna go. I go, and I’m locked in. I felt like I actually belonged somewhere, and I was like, ‘I’m gonna do this.’”

Despite Oreto’s resolve, her entry into the tattoo world was no easy feat. She set out to find an apprenticeship, but was turned down again and again, thrown out of countless shops because she was a woman.

“One guy actually told me the only reason a woman should be in a tattoo shop was either sucking dick or answering the phone,” she said.

When she finally found a mentor willing to teach her, another male tattooer working in the shop threatened to quit. Luckily for Oreto, her mentor resolved to teach her anyway, and the disgruntled colleague packed his things and left. Though she had finally found an apprenticeship, Oreto said she felt as if she had to work harder than her male colleagues to prove her worth. And she wasn’t the only one.

After hearing that many of her colleagues and friends had experienced much of the same treatment, including what she described as “the common things, a little bit of sexual harassment,” the artist eventually decided to open her own shop in Philadephia — one that would cater not just to women, but to anyone who felt excluded by the traditional tattoo space. With Now and Forever Tattoo, she wanted to transform the tattoo experience, facilitating for artists and clients a more welcoming space than the one she grew up with.

After wrestling her way through the trials and tribulations of old-school, traditional tattooing, she decided to take a stand against some of its flaws, instead creating a women-led, inclusive atmosphere and hiring young, self-taught artists. Physical services are important to Oreto, but so is a general atmosphere of inclusivity. The identities of her two children — a 21-year-old transgender son and a 20-year-old queer son — have helped fuel her desire to create a safe space. And for some, these efforts seem to resonate.

“Oreto is a magician,” wrote one reviewer, who said that they and their partner have been getting tattooed by the artist for over a decade. “As a trans person, tattoo shops can feel intimidating, but Kristel has always been professional, welcoming, caring and knowledgeable.”

Now and Forever Tattoo opened in 2022, funded by the money Oreto earned from her X-rated OnlyFans profile that helped sustain her and her family during the height of the pandemic, a time when many tattoo artists were put out of work completely. The shop is situated on Philadelphia’s bustling Front Street, marked by a larger-than-life black candy heart design plastered to the storefront’s floor-to-ceiling window. The interior is brimming with life and color.

Now and Forever differs drastically from the traditional tattoo shop, still reminiscent of the bikers and punks that once dominated the scene. Heavy metal music, pictures of nearly naked women and harsh language may come to mind when picturing the traditional tattoo experience — and for a long time, this was not an incorrect characterization.

At Oreto’s shop, though, vintage furniture upholstered with bright shades of velvet forms a living room-like huddle, and gilded gold mirrors line the walls. Ceramic animals — a leopard, a parrot and at least two tigers — are scattered throughout, and a taxidermy gazelle, deer and moose join the bunch. A vintage gumball machine filled with flowers, and ornate stained glass lamps radiating multicolored light add finishing touches to the already sense-shattering, yet somehow quite calming, space. The tattoo chairs almost feel like an afterthought, here and there throughout the multi-level studio.

But this is merely the backdrop for the new level of service offered by Oreto and the artists who rent her space. None of them are professionally trained in trauma-informed care, and they don’t advertise it. However, Oreto said that the principles are constantly front of mind and integral to her practice.

At Now and Forever, clients are offered pillows, privacy screens, and drinks and snacks from a full service kitchen. Oreto’s learned how to make herself feel comfortable when getting tattooed, with over 20 years of experience in doing so, but wants new clients to feel at ease during the painful process too. She recognizes that not everyone will know how to care for themselves during the process.

“I’m constantly checking on my person,” she said. “When I go get tattooed, no matter what shop I go to, I’m rolling with a goodie bag — I got snacks, I got a drink, I usually got a gummy, I got a joint rolled. I am ready to go. But somebody else coming in might not be as prepared as I am. It definitely makes the process easier on everybody — It’s an intimate process regardless.”

Like Bakaty, Oreto acknowledged that the traditional apprenticeship model is observed for a reason, but thinks it should be a lot quicker than the five-to-six-year model Bakaty referenced. She said that apprenticeships have gained a bad reputation, based at least partially on rumors and partially on lived experiences. Now, she said, the industry is in an “in-between world,” with some still enduring the status quo and others, perhaps impatiently, resolving to learn how to tattoo on their own.

She agrees that much of traditional tattoo knowledge is lost in this shift — from practical skills like how to respond when a client passes out in the chair, to the historical and cultural knowledge that old-school artists like Bakaty yearn for. She feels disrespected by young artists who don’t care to learn about artists like her and her predecessors, who painstakingly paved the way for today’s tattoo artists’ ability to work freely.

“I had to fight to get where I was, like literally fight,” she said. “Not knowing that history of it is terrible — you have no idea where any of this started, or where it came from … If you’re going to do this and dedicate your life to it, then you should have enough respect for the craft to find out how you were able to do this.”

Some younger artists, even those who have not undergone traditional apprenticeships, still understand and appreciate what the old-school model imparts. They aren’t necessarily dismissive of the tradition, as some old-school artists assume, but simply found that it does not work for them. For instance, Marcella Harvi, who works under the name “MothMommy,” taught herself how to tattoo. Starting in 2018, she was tattooing from home, but she met Oreto last spring and opted to join Now and Forever.

Harvi’s feelings about traditional apprenticeships are complicated. Because the pandemic coincided with her beginnings as a tattooer, she didn’t have the opportunity to complete a traditional apprenticeship at the start of her career — something she, to some extent, regrets. She said that even if COVID-19 hadn’t impacted the trajectory of her career, though, she may have been hesitant to start out in an old-school shop, referring to traditional space as “trad.”

“There’s sort of this ‘trad’ attitude of like, ‘Oh, you have to earn your spot, pay your dues. I went through this, you have to too, this is just the way it is,’” Harvi said. “It’s like, sure, learn, but you don’t have to be abused to do this job. You don’t have to go through all that.”

Harvi said that the industry has shifted a bit, allowing self-taught artists like her to enter the traditional scene to an extent, and for women and nonbinary folks to feel more comfortable. Although she’s proud of her self-taught status and feels lucky to work out of an inclusive shop like Oreto’s, she sometimes wishes she had a more old-school upbringing. She said that, at the beginning of her tattooing experience especially, she did some work she isn’t incredibly proud of. The permanency of the work she did while learning weighs on her to this day.

“I’ve come to respect the traditional way to do it so much more,” Harvi said. “Part of me is like, ‘Damn, I wish I was trained traditionally,’ because as there’s so much that I don’t know, and I have been just kind of like fucking around my entire career and just being like, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing, but I guess this is right.’”

Since starting at Now and Forever, Harvi said she has learned a wealth of information and wisdom from Oreto. She appreciates the safe space the more experienced artist has created, and leans into the resources the arrangement offers, including some of the trauma-informed practices.

Rachel Stover, another tattooer who started working at Now and Forever within a few months of Harvi, is also self-taught, and runs into the same conflict: Do the benefits of being self-taught outweigh the costs of losing out on a traditional apprenticeship?

Stover, who can be found online under the name “tuffbabytatts,” said they think traditional tattoo culture is still a “boys club,” recalling male tattooers their friends worked with that were, as they described, “fucking mean.” But Stover, too, sees the industry changing, opening up to more people like themself.

Before starting at Now and Forever, they exclusively did stick and poke tattoos, done without the electric tattoo gun found in most shops. They learned how to use the machine with Oreto’s help, and said they were grateful for the uniquely supportive environment they found at her studio.

“People want to share information more now, and part of it is from this healthy place of seeing that people are going to tattoo no matter what, and wanting them to have the knowledge of how to do that better or more safely,” they said. “It’s wanting to impart that information so that people can grow more quickly and do less damage to bodies, because you can screw people up really quickly if you’re tattooing with less precise techniques or the wrong equipment.”

Stover said that this change is a win-win, allowing younger artists to forge their own paths in the industry by offering a level of care, concern and safety they don’t find when visiting ‘trad’ shops themselves.

“If [Oreto] gives us the space to work more safely, and also the opportunity to learn how to do what we do even better, that’s a mutually beneficial situation,” Stover said. “Nobody loses.”

You Tell Them to Shut Up

Just a few miles south of Now and Forever sits one of the city’s oldest tattoo shops; Philadelphia Eddie’s Tattoo. The shop was established by Crazy Eddie Funk, whom the still-standing shop’s website describes as “a legendary tattooer and a fierce friend.”

“‘Crazy Philadelphia Eddie,’ born Edward Funk, sprang from the beer-and-blood soaked tattoo parlors of Coney Island, New York, circa 1952, to dominate the Philadelphia tattoo scene so completely that he took the city’s name as his own,” reads a 2004 Philadelphia Inquirer article written ahead of his retirement at age 67.

Eddie chose his career path at age 15, and never looked back. When the tattoo ban hit New York City, turning most of the market underground, Eddie moved to Philadelphia and set up his own shop. He sold supplies from his own company, United Tattoo Supply Co., and traveled the world to tattoo. At the time, tattooing was reserved for rebels, military men, gangsters and bikers — biker culture is still inextricably linked with the tattoo scene, with large groups of Harleys still flocking to tattoo conventions across the country.

Eddie, a biker himself, adopted a wild life as well. In a 2016 documentary, he said he’s been married four times — two of them were sisters, and one of them he married twice, something he described as “a real fuckin’ no-no.”

“Since I was a kid, people called me crazy,” Eddie said in the documentary. “I didn’t give a fuck.”

His influence went far beyond the stencil, too. “I only drink screwdrivers because Eddie drinks them,” one young artist said to the Philadelphia Inquirer at a toast for the legend’s retirement.

Though the industry longstay passed away in 2016, he sold his shops to tattooers that worked for him, and his legacy lives on in two shops — one in the city’s Chinatown neighborhood, and another on South Fourth Street. One member of the original crew, who goes by the name Eastcoast Charlie, still tattoos regularly from the Fourth Street location.

Though most of the crew has passed on and dispersed, some younger artists have joined and taken on the shop’s history. Clay William Willoughby, who works at the Chinatown shop, has been tattooing for nearly 20 years. In a conversation that took place on a scratched-up, wooden church pew pushed against the shop’s side wall, Willoughby shared some glimpses into the studio’s rich and rocky history, including a story about one tattooer who died in the shop’s lower level.

“He had a heart attack or stroke in the basement or something — he was actually living down there. It’s full circle,” Willoughby said. “It started out as one of those rough shops. Eddie was with the Pagans or the other motorcycle club that was around, I forgot their name. He was crazy Philadelphia Eddie, and this is his shop.”

Eddie’s shop atmosphere is much more traditional than Now and Forever. The space is awash in loud music and the faint smell of cigarette smoke, both blending with the sound of buzzing tattoo guns stationed throughout the fairly small space. The walls are lined with oversized flip books and frames of flash tattoos — pre-drawn designs that are typically framed to display artists’ work and spark inspiration for walk-in customers who aren’t sure what to get permanently impressed onto their bodies.

One wall features flash branded with “Sailor Jerry” stamps, a reminder of one of the tattoo industry’s most influential figures. Unknown to most outside of the tight-knit traditional tattooing sphere, Jerry is behind many of the traditional American tattoo designs, seen everywhere in shops, but less and less on people’s bodies.

Born Norman Keith Collins, Sailor Jerry enlisted in the U.S. Navy at 19 years old. While mostly tattooing men in the Navy, he traveled to Southeast Asia where he picked up inspiration for many of his signature designs. He was known for drawing nude pin-up girls, anchors, snakes, dice and bottles of alcohol, and many old-school artists adhere to his designs, or new iterations of them, almost religiously.

Eddie’s shop remains an old-school institution, but even the artists it employs have noticed a shift in the industry. The intimidation factor of traditional shops — ripe with the residue of biker culture and heavy metal music — has begun to fade, giving way to shops more like Now and Forever. The pillows, complimentary snacks and constant communication offered at Oreto’s shop don’t exist at Eddie’s — and it doesn’t seem as if they ever will.

“You give them a beer, give them a number, and, you know, make friends with them,” Eddie told the Philadelphia Inquirer, of his customers, in 2004. “And you tell them to shut up.”

Willoughby doesn’t have a problem with the new types of shops, though he described them as more “spa- or boutique- related,” with a sigh. He recalled being frightened by the typical tattoo shop when he was first starting out, describing the scene as “a bunch of bikers and burly burly-looking dudes” who were “always in a bad mood.” Information — like how to make equipment or where to buy supplies — was not accessible, and the industry was based on skill alone, not inclusivity or feeling.

“When I started, there was no information — you had to get everything through apprenticing at a shop, hoping the guys you’re working with are giving you real information, not disinformation,” Willoughby said. “Back then, the goal was they wanted you good enough to take little walk-ins but not good enough to be better than them. What took me a year to figure out, people can do in a month, because it’s all at your fingertips.

Willoughby said a market still exists for traditional shops and, though his clientele has shifted a bit, he’s been able to navigate the industry as it changes. Though he doesn’t want new artists to go through what he did, he said much of the tradition of old-school American tattoo is being lost with a new generation of tattooers and their ideas.

“Bottom line is, the traditional part of tattooing is to have fun and make a dollar,” he said. “You’re an artist, but you’re not restrained by the art world. You don’t care about whose gallery show is where, because you’re making art every single day. And people have to live with it. It’s the only canvas that talks back.”

Martin LaCasse, who’s been tattooing at Olde City Tattoo — a shop just a couple miles from Eddie’s — for 22 years, had a similar experience as an apprentice. He recalls being forced to trace flash designs that were hung where the walls met the ceiling, all the way around the shop. When he finished one row, the shop would pay him $10. Then, he would start again.

Though the multi-year apprenticeship was taxing mentally and physically, he stuck with it, in hopes of becoming a full-fledged tattooer. “I wanted to do it really, really bad,” he said.

Of trauma-informed or therapy-based tattooing, LaCasse wasn’t too sure.

“I did not know that people were trying to do this, and make it with this therapy thing,” he said. “Not my style — will never go along with that. But to each their own. I’m sure there’ll be a clientele for it.”

Although he does have clients who want to talk about their trauma — he said he’s done tattoos where a client will bring a deceased relative’s ashes and he’ll mix them with the ink — it isn’t his style to engage.

“I just kind of let them talk — sometimes it’s just them talking,” LaCasse said. “I’m not really listening. I’m like, I’ve got enough problems on my own here.”

The Re-Indigenization of Tattoo

Though much of the trauma-informed and new age tattoo trend caters to younger generations, in a sense it can also be seen as a return to the past of tattooing — one that began long before tattoos arrived in America. Tattooing has been practiced in nearly every culture, going back thousands of years, the first discovered tattoo dating back to at least 5,000 B.C.E. Lars Krutak, who identifies as a “tattoo anthropologist,” described the ritual nature of tattoo across Indigenous cultures, one which is reflected, at least in part, in some of the newest tattoo trends promulgated by artists like Pili and Santibañez.

“Across the Indigenous world, tattooing was almost universally ritualized because it reenacted ancestral practices and mythic traditions, binding each tattoo recipient to a deeply felt collective history,” Krutak said in an interview. “In turn, tattooing traced a pathway through the world that individuals navigated in the attempts to acquire new knowledge of themselves, their cultural past, and their position in the world.”

Much of this Indigenous tattoo practice continues today too, with artists around the world carrying on their cultures’ ink-based traditions. Holly Mititquq Nordlum, a traditional Inuit tattooist from Alaska, works out of her home, giving friends, family and community members traditional chin and knuckle tattoos, each of which is rooted in Iñupiaq folklore. A short, two-part documentary she co-produced in collaboration with the Anchorage Museum, titled “Tupik Mi,” explores her connection to the craft and the emotional charge behind these traditional tattoos.

“In Inuit culture, art isn’t a separate thing. It’s part of everyday life,” she said. “And it has a lot more to do with spirituality — honoring everything, and finding everything beautiful, and representing that in some way. And then the tattoos, of course, are a natural extension of that.”

In the documentary, an Inuit woman named Eva receives a tupik chin tattoo — a mix of several full and dotted lines emanating from just below the lips to the bottom of the chin — from Nordlum. She looks in the mirror and tears up, quietly contemplating the new addition. Nordlum, too, said that she was struck by the feeling she experienced just after getting her own.

Tattooing is about community and connection for Nordlum. Though the artist identifies as a “healer” and acknowledges the importance of emotional repair through tattoo, especially when tied up by so much ancestral history, she knows her limits.

“I can’t bear the burden of each story, right?” she said. “So, when they come in, I listen. I care. I love, I cry, I hug — it’s all wonderful. Then, they leave, and I don’t remember shit. Like, I just can’t take that on. I mean, I have to, I am a product of trauma as well, so I don’t need more of it.”

This connection to the tattoo world, which reaches back much earlier than the dawn of American tattooing, isn’t lost on some of the new-school artists creating a place for themselves in the industry. Pili, the artist working in Baltimore who aims to reconnect to this kind of practice, doesn’t see what they’re doing as new — their practice is merely a return to the work Nordlum and other Indigenous artists have been doing for centuries. They see their spiritual work and Santibañez’s trauma-informed work as a reminder of what tattooing has lost, and a celebration of what it can become again.

“All of this is part of a larger re-indigenization process of tattooing and a remembering, a revisiting, a revitalizing of the original intentions behind tattooing, which is not specific to any people,” Pili said, explaining the vast array of cultures that tattooing has presented itself in over time. “This is something that we all had a connection to, and that we all still feel really called to. I think it’s a really special portal.”

For Pili, the potential for the growth of this kind of tattooing is limitless. Nordlum, a native Alaskan who now lives in a largely Republican state and neighborhood, recognizes the backlash her traditional tattoos, often very visible on the chin and knuckles, can sometimes cause. “Every white dude and every white, old lady’s gonna give you a dirty look — that is a given,” she said.

Pili, who said that they used to be nervous that their tattoos would hold them back in society, recognizes a political power laden in this sentiment.

“Tattooing, for me, is a way of having these decolonial, radical discussions and creating a safe space for people to really remember who we were before fear separated us and made us betray one another, and betray ourselves,” they said.

The New Tattoo?

Whether a new phenomenon or simply a reconnection with tattoo traditions tracing back thousands of years, trauma-informed tattooing — and trauma-informed everything — doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. But even though it’s impacting artists and clients alike, it’s unlikely to disrupt the tradition of the old-school tattoo shop entirely.

“People aren’t just paying for tattoos, they’re paying for an experience,” said Dusty Kiskaddon, a sociologist and tattoo artist who works in Portland. “They’re paying for a chance to have a certain kind of interaction with someone, and to leave that interaction with something they’re inspired by.”

While completing his Ph.D., Kiskaddon became a tattoo artist. His dissertation, “Blood and Lightning: The Embodied Production of a Tattooer,” investigated the “embodied labor of tattooing,” or the ways in which tattooing impacts artists physically, mentally, emotionally and morally. The work, which Kiskaddon will elaborate on in a book set to be published next year by Stanford University Press next year, was largely informed by his experience as an apprentice and work as a tattooer. He tattooed over 400 people as part of his ethnographic research, and said that one of his favorite parts of the tattoo industry is its versatility.

“Even in the same neighborhood, you could have a biker shop, where no one in there is going to ever have discussed consent in the way that you would talk about it in the shop that’s like six blocks away,” Kiskaddon said. “It’s really awesome that there’s a sort of plethora, or rather an ecosystem, of tattooing that can kind of cater to some experiences in a way that it’s almost specialized.”

Kiskaddon said that, in his experience, trauma-informed tattooing has allowed people from previously excluded backgrounds to get tattooed and find a real place within not just a shop, but in the industry as a whole. “That discourse matters — it’s important that people are talking about bodies, about race, about trauma, about identity, about fatness,” Kiskaddon said.

But, as he added, tattooing doesn’t always have to be like this. Sometimes artists should stick to their roots.

“People like to go get tattoos too, it doesn’t have to be all meaningful and intense,” Kiskaddon said. “There’s room for everyone — some tattoos are done over beers while listening to loud music, because someone wanted to have, like, a really rad Saturday.”

Abby graduated from New York University with a degree in Journalism and English Literature in 2023. During her studies, she worked with New York City publications including NY1 and the New York Daily News, and served as the Managing Editor of the Washington Square News. Over the past year, she worked in lifestyle journalism with Better Homes & Gardens and Homes & Gardens, and she is now pursuing a master’s degree in Investigative Journalism at City, University of London.