The Satmar rEvolution

Hasidic Williamsburg’s insularity is being threatened by smartphones, education, and economic mobility

by Dani Bronstein

Page 1

I dropped my baby blue iPhone in a shallow puddle. All eyes in the packed changing room shifted to the shiny new technology at my feet. Luckily none of the Satmar Hasidim, brushing and twirling their damp sidelocks, called me out in Yiddish, which I do not speak. I finished getting dressed, dropped my towel in the bin, and left the mikvah, the Jewish ritual bathhouse, where I once followed a young Satmar as desperate for a spiritual cleansing as I was and climbed over the locked turnstile to gain entry.

Two rooms flank this men-only bathhouse in ultra-Orthodox South Williamsburg, which the Hasidic sect of Satmar dominates. Each morning the rooms attract a constant stream of prayer gatherings of the requisite 10 men. I often pray there and am never questioned for looking out of place. But the kids tend to stare in confusion at my white Nikes and my lack of side locks or the standard-issue frock coats, called rekels, that Satmars wear on weekdays.

This day, the sight of my dropped smartphone coincided with a young Satmar’s diatribe in Yiddish that shot from angry to funny. I had no trouble discerning the gist of his jokes—something about secular Internet usage—and the scared reaction of his listeners as he further warned against exposing their children to these diabolical devices. In perfect irony, two of the men took out their smartphones as he rattled on. Smartphones appear to be the latest incursion in a constant struggle to stave off the contemporary, the secular, and the hip in the still very insular universe that is Satmar Williamsburg.

In another basement, less than a 10-minute walk across the Satmar shopping thoroughfare of Lee Avenue, a different mood prevailed. Down six stairs was an off-the-radar shtiebel, an informal mini-synagogue that functions as a haven for a group of somewhat more progressive Satmars. It has since moved to a new dingy basement locale. Some of its congregants are Zionists; all of them want to study Kabbalah and the greater canon of Jewish thought. They wield their smartphones with the same familiarity they argue over passages of Talmud—without apology. Needing a place to meet without judgment, the not-quite-clandestine gathering started in a center for rebellious Hasidic youth. Every night, a group of married men would gather to study Jewish texts in this more intellectually open environment than is common in the community.

Since inception, the need for their synagogue has been hard to explain to other members of the Satmar community. For the Satmar faithful, to create a space for studying, praying, and exploring their Jewish Identity without a rabbi in charge, an agenda, or explicit goal, is just plain alien. Here was a group of men who elected to stay within the ideological confines of the community in the way they speak and look. They’re not like the Apikorsim, apostates who the modern world has led astray to secularism. But they choose to let in just enough of the 21st century without breaking any of the bonds the community imposes. They also ignore the warnings that if they use the Internet in an unrestricted way, their children will get pulled out of the Satmar private schools. The reality is that while the ultra-Orthodox primarily use their electronic devices for work-related matters, once the Internet is in their pockets, the world becomes vastly more accessible. And alluring.

The Satmars have been living in Williamsburg since they arrived from Holocaust-ravaged Hungary 70 years ago. The hipster invasion of Williamsburg since the 1990s has moved South, surrounding the largely Latino-populated public housing projects with bars toting “bearded mixologists.” Although dubbed by some Satmar as a “plague of artists,” gentrification has not yet managed to cross Broadway and infiltrate the enclave of this Hasidic sect. Interviews with dozens of Satmar men, both those within the community and those who have left, make clear that the Yiddish-speaking population of South Williamsburg—while exploding from 4,500 to 57,365 in 70 years, including a 41 percent Jewish increase in Williamsburg since 2002—is experiencing evolutionary challenges to its otherwise self-enforced insularity.

A fascination with Hasidism has led me to an intense, sometimes envious questioning of the steadfast rigor that is Satmar’s style and the way it defines the anti-secular, God-centered, lives of its adherents. Equally fascinating to me has been to see how the 21st century and its technology have begun to challenge community life in exceedingly serious waves. There is growing discontent with the level of secular education that children receive—it stops at the elementary level—and with the way that culture has stymied economic mobility for so many of the community’s members. The lures of the 21st century have made it harder to maintain the imaginary ghetto walls erected in the 1940s and ‘50s when the first Satmar immigrants first came to Brooklyn.

Page 2

One de facto leader of the basement synagogue is a soft spoken father of four, soon to be five, who in his spare time studies nutrition and gives classes on Jewish texts.The Internet introduced him to core concepts of Judaism and Hasidism that his Satmar upbringing omitted. Unlike most old-school Satmars, he hopes to move his family to Israel, to have his children learn English, and perhaps for them to even pursue secular professions. In his view, healthy use of the Internet makes more sense than creating an endless number of filters. All the same, he understands why the leadership has pushed filtering in its attempt not to “lose the grip on the youth, the people, the community.”

Filtered or not, he thinks Hasidim who surf the Web will open up to the ideas of foreign people, cultures, and even moral codes. “The problem is, a lot of the leaders in the community . . . just say, ‘Run away from the Internet—just close your eyes and run away.’ It’s not going to help you,” he said. “It’s going to run after you, and it’s going to run faster than you can. It’s going to catch up with you.” The leadership obliges any Satmars with an Internet connection to pay a monthly fee for a filter that reports their browsing histories to the leadership.

In a warren of tiny office suites not far from the largest Satmar supermarket, a reporter for Satmar’s daily Yiddish newspaper, who also freelances as a Yiddish translator, cleared a pile of discarded papers off the chair so I could sit down. He is about the same age as the nutritionist, but with a higher child count by two. Clearly, he is more entrenched in the conservative community’s groupthink while he explains the grand Rebbe’s position on Internet use. He mentioned Meshimer, “an Internet Filtering Solutions Company” that wards off the Internet’s power to “cause spiritual and practical destruction in your home and business,”

“an Internet Filtering Solutions Company” that wards off the Internet’s power to “cause spiritual and practical destruction in your home and business,”

according to the company website. Community members pay fees that help defray the cost, but the translator said the the Satmar leadership spends something like $50,000 a month to set up and maintain the service.

He showed me the hologram on his ancient smartphone, a sticker that declares to everyone in the community that he has installed the rabbinically approved filter. Clicking around on a desktop computer that is even older than his smartphone, he showed me how Meshimer blocks him from going to sites such as YouTube or Facebook. The Rebbe “requires everyone, that if you want to send your kids to our schools you need this filter.”

All the same, the translator admits that the neighborhood is much more open to technology than it once was. “I don’t say it in a good way, but that’s a fact.” He acknowledged that to control Internet usage is much more of a challenge than it was to enforce the first Satmar Grand Rebbe’s ban of television ownership in 1955.

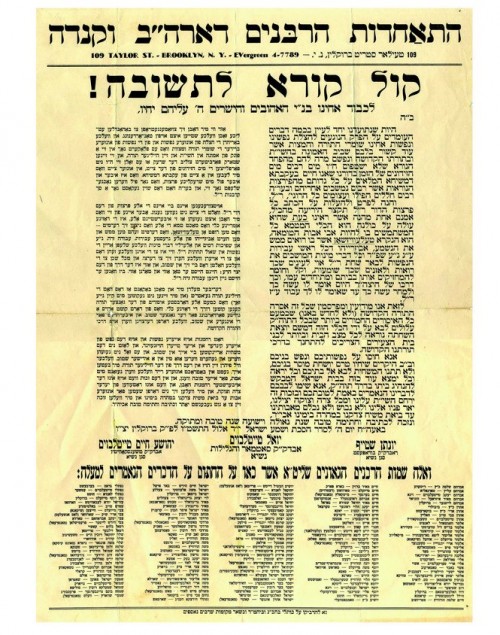

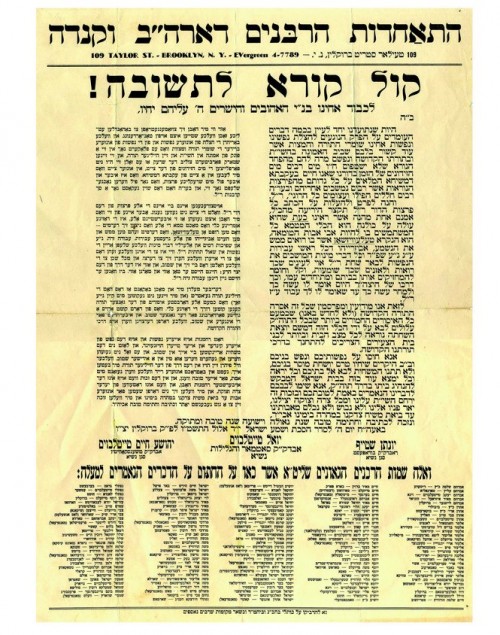

Ultra-Orthodox ban on Television ownership posted around Brooklyn from 1955. Signed by delegation of 150 rabbis, headed by Joel Teitelbaum, original Satmar grand rebbe.

Ysoscher Katz grew up in Satmar Williamsburg, across the street from my very same mikvah. The yeshiva he attended in the Satmar enclave of Kiryas Joel, NY, expelled him when friends found a Hasidic text with banned commentary under his dorm room bed. He is now the pulpit rabbi at Prospect Heights Shul and a recognized Talmudic scholar in the modern orthodox community. Katz is also the Director of Jewish Studies at Luria Academy of Brooklyn—where we met up to chat all things Satmar. He is mindful of the tension between the way technology has started to penetrate the community against the efforts of those who “are going to try very hard to maintain whatever semblance of insularity” they have left.

Among his activities is an organization he co-founded called Frum and Stuck. It focuses on counseling Hasidim on the fringe before they make a challenging move to leave the community for good. Most stunning of all has been the number of women who have reached out to the counseling center. Repeatedly their stories have been about the monotony of their insular lives as housewives and caregivers. “So they got a computer and it had Internet installed,” he said, “and that’s it—then it’s over.”

Shulem Deen first encountered the Internet in 1996 through a standard AOL CD-ROM sent to houses throughout the world. We met up for coffee in midtown the week before the release of his 2015 memoir, All Who Go Do Not Return. It tells the story of leaving his wife and five children in the upstate New York Hasidic enclave of New Square. Custody battles ensued and the leadership of this Skver community sided with Deen’s former wife to keep the children away from him as he moved into an irreligious secular life.

All Who Go Do Not Return by Shulem Deen

Deen recalled how in the 1990s the Internet was new and foreign enough to Hasidim that a member of the sect’s “modesty squad” asked one of Deen’s friends if his computer’s microphone was the Internet. For Deen, the Web became “a portal to interact with people . . . from all over the world.” It shocked him to learn that Jews who were not Orthodox studied Maimonides and Talmud. The Internet provided him with his first encounter with other streams of thought outside of Hasidism, beyond his Pakistani car mechanic or the Latino clerk at the bodega.

The nutritionist seemed to speak at arm’s length from his Satmar community when he described the prohibitions the Grand Rebbe has attempted to enforce. “Even if the Satmar Rebbe talks to his community—let’s say he is going to be successful—40 percent [of the community] is going to listen to him.” Even that segment of the population, “in five, 10 years down the road, they’re going to do it anyway, since the Internet is coming more and more into life.” He is confident that the speed of innovation on the tech side will always outweigh the barriers to entry for this closed-off society.

For the nutritionist, it is God who has opened up access to the technological world. “He wants us to make a conscious decision—wants a person to say, ‘I can go on whatever website I want to go, but I choose not to, because it’s not good for me’.” Even with all of the infighting about the Internet, “if you open any local publication, you still find all kinds of [advertisements with] mentions of Websites, Twitters, and Instagrams.”

“The whole community runs on the Internet,” he went on. “The Rebbe’s institutions also run on the Internet.” He thinks ultra-Orthodox constituents should be asking themselves, “Am I just a Jew because my father raised me this way?” Or are these choices individuals make on their own.

Page 3

Insularity, however, also has its benefits. Despite struggling with poverty, 90 percent of households give charity. Their donations mainly stay within the community, going to organizations including Bikur Cholim, which delivers homemade meals to Jewish hospital patients and their visitors, or Chevra Hatzalah, a Jewish volunteer ambulance corps started in the 1960s. I watched a Satmar woman check out at the local Satmar corner store with what I can only describe as Yiddish food stamps. One of the few elder Satmar in the basement synagogue had told me about this no-publicity kindness that could sometimes, at a big kosher Brooklyn supermarket, mean the transfer of more than $20,000 a month from the wealthier to the poorest customers.

Eizur l’mazone translates as “Help for Food.” At the corner store, I bought spicy herring and babaganoush for less than $10 and asked the young Satmar cashier to add another $5 to my bill. I said the two magic words—Eizur l’mazone—and they instantly connected me to the community’s inherent kindness via an entry of my contribution—entered on the little shop’s computer. My gesture would mean that someone in my neighborhood, a less fortunate Satmar, would have a little more to spend on weekly groceries.

Chesed translates as “loving-kindness” in the Coverdale Bible. In the Satmar community, it is a non-profit organization that offers non-emergency medical transportation and visits to the sick. There are more than 400 volunteer drivers in Williamsburg alone. It rivals Uber in efficiency but far surpasses it in compassion. Most importantly for a large number of Satmars, is the price. The service is absolutely free.

One Satmar volunteer is 32 and married with six children. He works as a kitchen cabinet salesman but makes time to drive every week. His passengers are often family members going to visit the sick, which is of high spiritual value. “We don’t want people to think twice about visiting sick family because of the expense of a car, or time commitment of a long subway ride,” he explained. In this way, he ventured, “Constant visitors help the mood of the sick and let the doctors know this is a priority patient.”

Although Chesed does no publicity or fundraising, it manages to run a volunteer dispatcher six days a week—only stopping for the 25 hours of the Sabbath from sundown Friday to three-stars-out on Saturday. Its drivers are able to handle 90 percent of trip requests. That means 50,000 trips per year, just shy of 160 trips every single day.

Volunteers do a training course, the cabinet salesman explained, and never take payment, even when it is offered. “I tell them that if they pay me, then I do not get the mitzvah,” a good deed from religious duty, he said. The drivers also work all hours because “a [Hasidic] mother leaving Columbia Presbyterian at one in the morning is not going to feel comfortable taking a yellow cab.”

“a [Hasidic] mother leaving Columbia Presbyterian at one in the morning is not going to feel comfortable taking a yellow cab.”

Although not a member of the community, I registered for Chesed to go to my weekly physical therapy appointments in midtown Manhattan. I had trouble discerning the enumerated options that the automated answering system offered in Yiddish, so I just pressed zero, hoping someone live who spoke English would pick up. A minute or so of Jewish music filled call-waiting before a woman said hello in a heavy Yiddish accent.

“This is Dani’el Da’veed Bronshteyn,” my Hebrew name, delivered in my best approximation of a Yiddish accent.

The woman on the other end of the line switched to an almost perfect English. She asked for my pickup location, drop-off medical center, and appointment time. Ten minutes before the given pickup time I got a call with a similarly automated Yiddish message—this time with some familiar terms, including Minivan.

The volunteer driver behind the wheel was cordial enough, especially after some back-and-forth confirmed that I was indeed Jewish. Crossing the Williamsburg bridge, the packed M train passed us, reminding me how good it was to be able to avoid the claustrophobic body-to-body rush hour and the back spasms those trips always seemed to induce. I was at my appointment in 30 minutes.

In a community where the average household has somewhere between seven and 11 children, what could be more important than school.

A 1961 survey counted 4,500 Satmar in Williamsburg. 50 years later 57,365 of Williamsburg’s 74,500 Jews identified as Hasidic in 2011. As the population grows, there are issues with finding space for Satmar girls to study. And ex-community members such as Naftuli Moster have been fighting for improvement in both the quality and quantity of secular education for Satmar boys.

I met Moster in a cafe in Forest Hills, and when he noticed my long beard and yarmulke—he sported neither—he immediately made sure to divulge that he was no longer what people consider Hasidic. Moster grew up in Borough Park as part of the Belz sect of Hasidim. He attended Belz schools until the age of 20. At 19, he found it impossible to enroll in secular college courses without a high school diploma or GED, neither of which Hasidic yeshivas award. On top of that, asked to submit an essay with his application, he didn’t even know what the word meant. These gaps in basic government-mandated education triggered his search into the legalities of what private schools, including Hasidic yeshivas, really should be providing. That led him to create an organization called Young Advocates For Fair Education, to bring lawsuits against ultra-Orthodox yeshivas that ignore state-mandated education requirements.

Katz, the Director of Jewish studies at Luria, a dual-curriculum, co-educational, Montessori school, thinks the English Satmar boys receive through grade seven is the public school equivalent of a third grade education. But still, he does not advocate for the dual-curriculum of modern Orthodox Jewish day schools, where he thinks the Jewish education offered is “significantly weaker and inferior” to that of the Satmar youth.

The solution that the nutritionist plans to apply when his oldest child gets to first grade is to augment yeshiva education with English tutoring at home. He quoted a Talmudic saying that Moster’s organization has plastered in Hebrew on a Williamsburg billboard: “A father has an obligation to teach his son a profession.”

Page 3

Page 4

Another Satmar father complained that even what is being taught within a strongly Jewish context can be problematic. A teacher called and threatened to expel his seven-year-old daughter if she kept asking questions about God. As disgruntled as he is, the family can’t afford to move her to one of the non-Satmar Jewish private schools because they only recently got off welfare. Public school, he said, would give his mother a heart attack.

He was so sensitive about imparting the information that we had to leave the Satmar cafe where we had met so that he could tell me the story in the privacy of his car. This father and many other Satmars I reached out to were only willing to speak to me on condition of anonymity—scared to become the next outcast member of the Satmar community like Sam Kellner, for tattle-taling on other members of the community to anyone outside.

Moster’s provocative billboards have triggered some backlash in the Satmar community but he is thrilled that their slogans are generating conversation about the issues. Yet it annoys him that the leadership does not see his efforts as chesed. The strategy of Young Advocates for Fair Education, he said, is not to apply pressure on the Rebbe himself, but to reach government officials at the top, and constituents at the bottom to push to improve secular education within the Satmar schools.

Just like Moster, Deen, who managed to complete only one semester of community college, believes that opportunities for college or pre-professional programs will open when and only if Satmar boys are given adequate English preparation in school. If the status quo does not change, an uneducated new husband and father “has to sit with his wife to teach him how to just read basic words . . . so the potential [to enroll in college] does not exist.”

“has to sit with his wife to teach him how to just read basic words . . . so the potential [to enroll in college] does not exist.”

These modest educational opportunities feed into economic disadvantage when men lack the English skills to succeed in most professions, but also the computer skills required for the new technological jobs that are popping up. Moster said that the Hasidic communities in Borough Park and Williamsburg “rely more heavily on government assistance than Brownsville and Bed Stuy.” Everyone interviewed, both within and now outside the boundaries of the community, noted how adept Satmars were at working the system. But those wedded to the establishment, like the reporter/translator, point to the success stories that undergird the community, such as the family that owns and employs Satmars at B&H.

Poverty is far from a new issue for Satmar Williamsburg, with at least 33 percent of families there receiving public assistance by 1997. Colliding factors, including real estate hikes, high birth rates, and a lack of secular education or computer skills are making the problem more acute. A special 2011 report on poverty in eight New York counties declared Williamsburg the poorest Jewish area among them, at 55 percent poor and 17 percent near-poor Jewish households. The United Jewish Appeal’s report on Brooklyn Jewry also emphasized the massive population increases, noting that 50 percent of Jewish Williamsburg residents are under 18 and only 3 percent are over 65.

Satmar boys looking up at a helicopter passing by, while filling the street for celebrations related to a prominent Rabbi visiting from Israel. Photo Credit: Mark Hanover

Moster himself spent years working a dead-end job in a warehouse, as many young married Satmar men do. He said the community’s insularity helps residents share the secrets of maximizing government benefits. “Of course, a lot of it has to do with the fact that they’re very resourceful,” he said. ”if one person knows about the benefits you can get or the schtick you can do to get a certain benefit, and that’s where WhatsApp comes into play of course. Everyone gets that.”

Still, no one wants to be on welfare. The nutritionist sees two groups emerging financially in the community, the haves and the have nots. Half of the successful group, he said, “will flush it down as soon as they made it, because they have no organizational or financial skills.” Most of the community just goes paycheck to paycheck though, only surviving on government handouts. Without government funding, he said, the community “would have expired a long time ago.” In fact, government assistance makes much of the Satmar lifestyle possible for the poor, given the cost of kosher food, private tuition, and rising Williamsburg rents.

Deen accepts it as “a matter of course—people get married and they rely on government benefits, at least in the early years.” Katz, on the other hand, sees that the community is “going through serious convulsions—huge seismic shifts.” He sees very few middle class people anymore and blames this on the transition from industry to technology. Under the old system, the under-educated could eke out a living but technology requires skills many community members lack. Katz also wonders how the situation will evolve since his “brother’s six children will probably end up having six children of their own. How are they going to feed each other?”

“What does middle class mean when you have 12 kids?” was Deen’s rhetorical question.

“What does middle class mean when you have 12 kids?”

Deen was especially curious about the comfort I feel praying in Williamsburg, and the acceptance I feel praying in the basement haven. ”Maybe I’ll come another shabbos,” he said. He had followed that very same search for piety, or religious authenticity. I couldn’t help but compare our journeys as I listened to his recorded yiddish-isms on the train back to Williamsburg.

Once back home, I left my baby blue smartphone on my nightstand and ran through the snow to the mikvah and then to the basement synagogue to welcome the Sabbath. My garb had changed. I wore the black and silver patterned bekishe, the frock-coat designated for Sabbath and holidays, I had bought as a costume the previous month for the Jewish halloween-esque holiday of Purim. By no means did I fit in. Mine was an $18 polyester knockoff, with the pattern of a different Hasidic sect. It bore little semblance to the Satmar’s all black gorgeous silk bekishes that cost many hundreds of dollars. But I felt like royalty in my new robe.

Satmar teens during celebrations for a prominent Rabbi visiting from Israel. Photo Credit: Mark Hanover

Walking from services to the nutritionist’s apartment for a family Sabbath dinner, snowflakes were falling onto the tall fur streimels on the heads of those in our group of walkers and the hoards of other Satmars heading home to dinner. The south side of Williamsburg felt a lot like Satmar shtetl life back in Hungary a century ago. Across the street from the nutritionist’s apartment building a new luxury high-rise was going up, accentuating the neighborhood’s cultural divide.

We walked into his apartment, where the nutritionist’s wife was still praying and their four children were dressed up for the Sabbath, napping or playing quietly. All eyes lit up when their father walked in. Collectively, they jumped up to tell him about their week in school in Yiddish and received their traditional Sabbath blessings in Hebrew for the boys to be like Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Menashe and girls to be like foremothers Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. I helped the youngest into his high-chair and his mother nudged her older children to introduce themselves in English. She started asking me about my bekishe and beard intentions once the children had all gotten into pajamas and been put to bed.

Page 1

I dropped my baby blue iPhone in a shallow puddle. All eyes in the packed changing room shifted to the shiny new technology at my feet. Luckily none of the Satmar Hasidim, brushing and twirling their damp sidelocks, called me out in Yiddish, which I do not speak. I finished getting dressed, dropped my towel in the bin, and left the mikvah, the Jewish ritual bathhouse, where I once followed a young Satmar as desperate for a spiritual cleansing as I was and climbed over the locked turnstile to gain entry.

Two rooms flank this men-only bathhouse in ultra-Orthodox South Williamsburg, which the Hasidic sect of Satmar dominates. Each morning the rooms attract a constant stream of prayer gatherings of the requisite 10 men. I often pray there and am never questioned for looking out of place. But the kids tend to stare in confusion at my white Nikes and my lack of side locks or the standard-issue frock coats, called rekels, that Satmars wear on weekdays.

This day, the sight of my dropped smartphone coincided with a young Satmar’s diatribe in Yiddish that shot from angry to funny. I had no trouble discerning the gist of his jokes—something about secular Internet usage—and the scared reaction of his listeners as he further warned against exposing their children to these diabolical devices. In perfect irony, two of the men took out their smartphones as he rattled on. Smartphones appear to be the latest incursion in a constant struggle to stave off the contemporary, the secular, and the hip in the still very insular universe that is Satmar Williamsburg.

In another basement, less than a 10-minute walk across the Satmar shopping thoroughfare of Lee Avenue, a different mood prevailed. Down six stairs was an off-the-radar shtiebel, an informal mini-synagogue that functions as a haven for a group of somewhat more progressive Satmars. It has since moved to a new dingy basement locale. Some of its congregants are Zionists; all of them want to study Kabbalah and the greater canon of Jewish thought. They wield their smartphones with the same familiarity they argue over passages of Talmud—without apology. Needing a place to meet without judgment, the not-quite-clandestine gathering started in a center for rebellious Hasidic youth. Every night, a group of married men would gather to study Jewish texts in this more intellectually open environment than is common in the community.

Since inception, the need for their synagogue has been hard to explain to other members of the Satmar community. For the Satmar faithful, to create a space for studying, praying, and exploring their Jewish Identity without a rabbi in charge, an agenda, or explicit goal, is just plain alien. Here was a group of men who elected to stay within the ideological confines of the community in the way they speak and look. They’re not like the Apikorsim, apostates who the modern world has led astray to secularism. But they choose to let in just enough of the 21st century without breaking any of the bonds the community imposes. They also ignore the warnings that if they use the Internet in an unrestricted way, their children will get pulled out of the Satmar private schools. The reality is that while the ultra-Orthodox primarily use their electronic devices for work-related matters, once the Internet is in their pockets, the world becomes vastly more accessible. And alluring.

The Satmars have been living in Williamsburg since they arrived from Holocaust-ravaged Hungary 70 years ago. The hipster invasion of Williamsburg since the 1990s has moved South, surrounding the largely Latino-populated public housing projects with bars toting “bearded mixologists.” Although dubbed by some Satmar as a “plague of artists,” gentrification has not yet managed to cross Broadway and infiltrate the enclave of this Hasidic sect. Interviews with dozens of Satmar men, both those within the community and those who have left, make clear that the Yiddish-speaking population of South Williamsburg—while exploding from 4,500 to 57,365 in 70 years, including a 41 percent Jewish increase in Williamsburg since 2002—is experiencing evolutionary challenges to its otherwise self-enforced insularity.

A fascination with Hasidism has led me to an intense, sometimes envious questioning of the steadfast rigor that is Satmar’s style and the way it defines the anti-secular, God-centered, lives of its adherents. Equally fascinating to me has been to see how the 21st century and its technology have begun to challenge community life in exceedingly serious waves. There is growing discontent with the level of secular education that children receive—it stops at the elementary level—and with the way that culture has stymied economic mobility for so many of the community’s members. The lures of the 21st century have made it harder to maintain the imaginary ghetto walls erected in the 1940s and ‘50s when the first Satmar immigrants first came to Brooklyn.

Page 2

One de facto leader of the basement synagogue is a soft spoken father of four, soon to be five, who in his spare time studies nutrition and gives classes on Jewish texts.The Internet introduced him to core concepts of Judaism and Hasidism that his Satmar upbringing omitted. Unlike most old-school Satmars, he hopes to move his family to Israel, to have his children learn English, and perhaps for them to even pursue secular professions. In his view, healthy use of the Internet makes more sense than creating an endless number of filters. All the same, he understands why the leadership has pushed filtering in its attempt not to “lose the grip on the youth, the people, the community.”Filtered or not, he thinks Hasidim who surf the Web will open up to the ideas of foreign people, cultures, and even moral codes. “The problem is, a lot of the leaders in the community . . . just say, ‘Run away from the Internet—just close your eyes and run away.’ It’s not going to help you,” he said. “It’s going to run after you, and it’s going to run faster than you can. It’s going to catch up with you.” The leadership obliges any Satmars with an Internet connection to pay a monthly fee for a filter that reports their browsing histories to the leadership.

In a warren of tiny office suites not far from the largest Satmar supermarket, a reporter for Satmar’s daily Yiddish newspaper, who also freelances as a Yiddish translator, cleared a pile of discarded papers off the chair so I could sit down. He is about the same age as the nutritionist, but with a higher child count by two. Clearly, he is more entrenched in the conservative community’s groupthink while he explains the grand Rebbe’s position on Internet use. He mentioned Meshimer, “an Internet Filtering Solutions Company” that wards off the Internet’s power to “cause spiritual and practical destruction in your home and business,”

“an Internet Filtering Solutions Company” that wards off the Internet’s power to “cause spiritual and practical destruction in your home and business,”

according to the company website. Community members pay fees that help defray the cost, but the translator said the the Satmar leadership spends something like $50,000 a month to set up and maintain the service.

He showed me the hologram on his ancient smartphone, a sticker that declares to everyone in the community that he has installed the rabbinically approved filter. Clicking around on a desktop computer that is even older than his smartphone, he showed me how Meshimer blocks him from going to sites such as YouTube or Facebook. The Rebbe “requires everyone, that if you want to send your kids to our schools you need this filter.”

All the same, the translator admits that the neighborhood is much more open to technology than it once was. “I don’t say it in a good way, but that’s a fact.” He acknowledged that to control Internet usage is much more of a challenge than it was to enforce the first Satmar Grand Rebbe’s ban of television ownership in 1955.

Ultra-Orthodox ban on Television ownership posted around Brooklyn from 1955. Signed by delegation of 150 rabbis, headed by Joel Teitelbaum, original Satmar grand rebbe.

Ysoscher Katz grew up in Satmar Williamsburg, across the street from my very same mikvah. The yeshiva he attended in the Satmar enclave of Kiryas Joel, NY, expelled him when friends found a Hasidic text with banned commentary under his dorm room bed. He is now the pulpit rabbi at Prospect Heights Shul and a recognized Talmudic scholar in the modern orthodox community. Katz is also the Director of Jewish Studies at Luria Academy of Brooklyn—where we met up to chat all things Satmar. He is mindful of the tension between the way technology has started to penetrate the community against the efforts of those who “are going to try very hard to maintain whatever semblance of insularity” they have left.

Among his activities is an organization he co-founded called Frum and Stuck. It focuses on counseling Hasidim on the fringe before they make a challenging move to leave the community for good. Most stunning of all has been the number of women who have reached out to the counseling center. Repeatedly their stories have been about the monotony of their insular lives as housewives and caregivers. “So they got a computer and it had Internet installed,” he said, “and that’s it—then it’s over.”

Shulem Deen first encountered the Internet in 1996 through a standard AOL CD-ROM sent to houses throughout the world. We met up for coffee in midtown the week before the release of his 2015 memoir, All Who Go Do Not Return. It tells the story of leaving his wife and five children in the upstate New York Hasidic enclave of New Square. Custody battles ensued and the leadership of this Skver community sided with Deen’s former wife to keep the children away from him as he moved into an irreligious secular life.

All Who Go Do Not Return by Shulem Deen

Deen recalled how in the 1990s the Internet was new and foreign enough to Hasidim that a member of the sect’s “modesty squad” asked one of Deen’s friends if his computer’s microphone was the Internet. For Deen, the Web became “a portal to interact with people . . . from all over the world.” It shocked him to learn that Jews who were not Orthodox studied Maimonides and Talmud. The Internet provided him with his first encounter with other streams of thought outside of Hasidism, beyond his Pakistani car mechanic or the Latino clerk at the bodega.

The nutritionist seemed to speak at arm’s length from his Satmar community when he described the prohibitions the Grand Rebbe has attempted to enforce. “Even if the Satmar Rebbe talks to his community—let’s say he is going to be successful—40 percent [of the community] is going to listen to him.” Even that segment of the population, “in five, 10 years down the road, they’re going to do it anyway, since the Internet is coming more and more into life.” He is confident that the speed of innovation on the tech side will always outweigh the barriers to entry for this closed-off society.

For the nutritionist, it is God who has opened up access to the technological world. “He wants us to make a conscious decision—wants a person to say, ‘I can go on whatever website I want to go, but I choose not to, because it’s not good for me’.” Even with all of the infighting about the Internet, “if you open any local publication, you still find all kinds of [advertisements with] mentions of Websites, Twitters, and Instagrams.”

“The whole community runs on the Internet,” he went on. “The Rebbe’s institutions also run on the Internet.” He thinks ultra-Orthodox constituents should be asking themselves, “Am I just a Jew because my father raised me this way?” Or are these choices individuals make on their own.

Page 3

Insularity, however, also has its benefits. Despite struggling with poverty, 90 percent of households give charity. Their donations mainly stay within the community, going to organizations including Bikur Cholim, which delivers homemade meals to Jewish hospital patients and their visitors, or Chevra Hatzalah, a Jewish volunteer ambulance corps started in the 1960s. I watched a Satmar woman check out at the local Satmar corner store with what I can only describe as Yiddish food stamps. One of the few elder Satmar in the basement synagogue had told me about this no-publicity kindness that could sometimes, at a big kosher Brooklyn supermarket, mean the transfer of more than $20,000 a month from the wealthier to the poorest customers.Eizur l’mazone translates as “Help for Food.” At the corner store, I bought spicy herring and babaganoush for less than $10 and asked the young Satmar cashier to add another $5 to my bill. I said the two magic words—Eizur l’mazone—and they instantly connected me to the community’s inherent kindness via an entry of my contribution—entered on the little shop’s computer. My gesture would mean that someone in my neighborhood, a less fortunate Satmar, would have a little more to spend on weekly groceries.

Chesed translates as “loving-kindness” in the Coverdale Bible. In the Satmar community, it is a non-profit organization that offers non-emergency medical transportation and visits to the sick. There are more than 400 volunteer drivers in Williamsburg alone. It rivals Uber in efficiency but far surpasses it in compassion. Most importantly for a large number of Satmars, is the price. The service is absolutely free.

One Satmar volunteer is 32 and married with six children. He works as a kitchen cabinet salesman but makes time to drive every week. His passengers are often family members going to visit the sick, which is of high spiritual value. “We don’t want people to think twice about visiting sick family because of the expense of a car, or time commitment of a long subway ride,” he explained. In this way, he ventured, “Constant visitors help the mood of the sick and let the doctors know this is a priority patient.”

Although Chesed does no publicity or fundraising, it manages to run a volunteer dispatcher six days a week—only stopping for the 25 hours of the Sabbath from sundown Friday to three-stars-out on Saturday. Its drivers are able to handle 90 percent of trip requests. That means 50,000 trips per year, just shy of 160 trips every single day.

Volunteers do a training course, the cabinet salesman explained, and never take payment, even when it is offered. “I tell them that if they pay me, then I do not get the mitzvah,” a good deed from religious duty, he said. The drivers also work all hours because “a [Hasidic] mother leaving Columbia Presbyterian at one in the morning is not going to feel comfortable taking a yellow cab.”

“a [Hasidic] mother leaving Columbia Presbyterian at one in the morning is not going to feel comfortable taking a yellow cab.”

Although not a member of the community, I registered for Chesed to go to my weekly physical therapy appointments in midtown Manhattan. I had trouble discerning the enumerated options that the automated answering system offered in Yiddish, so I just pressed zero, hoping someone live who spoke English would pick up. A minute or so of Jewish music filled call-waiting before a woman said hello in a heavy Yiddish accent.

“This is Dani’el Da’veed Bronshteyn,” my Hebrew name, delivered in my best approximation of a Yiddish accent.

The woman on the other end of the line switched to an almost perfect English. She asked for my pickup location, drop-off medical center, and appointment time. Ten minutes before the given pickup time I got a call with a similarly automated Yiddish message—this time with some familiar terms, including Minivan.

The volunteer driver behind the wheel was cordial enough, especially after some back-and-forth confirmed that I was indeed Jewish. Crossing the Williamsburg bridge, the packed M train passed us, reminding me how good it was to be able to avoid the claustrophobic body-to-body rush hour and the back spasms those trips always seemed to induce. I was at my appointment in 30 minutes.

In a community where the average household has somewhere between seven and 11 children, what could be more important than school.

A 1961 survey counted 4,500 Satmar in Williamsburg. 50 years later 57,365 of Williamsburg’s 74,500 Jews identified as Hasidic in 2011. As the population grows, there are issues with finding space for Satmar girls to study. And ex-community members such as Naftuli Moster have been fighting for improvement in both the quality and quantity of secular education for Satmar boys.

I met Moster in a cafe in Forest Hills, and when he noticed my long beard and yarmulke—he sported neither—he immediately made sure to divulge that he was no longer what people consider Hasidic. Moster grew up in Borough Park as part of the Belz sect of Hasidim. He attended Belz schools until the age of 20. At 19, he found it impossible to enroll in secular college courses without a high school diploma or GED, neither of which Hasidic yeshivas award. On top of that, asked to submit an essay with his application, he didn’t even know what the word meant. These gaps in basic government-mandated education triggered his search into the legalities of what private schools, including Hasidic yeshivas, really should be providing. That led him to create an organization called Young Advocates For Fair Education, to bring lawsuits against ultra-Orthodox yeshivas that ignore state-mandated education requirements.

Katz, the Director of Jewish studies at Luria, a dual-curriculum, co-educational, Montessori school, thinks the English Satmar boys receive through grade seven is the public school equivalent of a third grade education. But still, he does not advocate for the dual-curriculum of modern Orthodox Jewish day schools, where he thinks the Jewish education offered is “significantly weaker and inferior” to that of the Satmar youth.

The solution that the nutritionist plans to apply when his oldest child gets to first grade is to augment yeshiva education with English tutoring at home. He quoted a Talmudic saying that Moster’s organization has plastered in Hebrew on a Williamsburg billboard: “A father has an obligation to teach his son a profession.”

Page 3

Page 4

Another Satmar father complained that even what is being taught within a strongly Jewish context can be problematic. A teacher called and threatened to expel his seven-year-old daughter if she kept asking questions about God. As disgruntled as he is, the family can’t afford to move her to one of the non-Satmar Jewish private schools because they only recently got off welfare. Public school, he said, would give his mother a heart attack.He was so sensitive about imparting the information that we had to leave the Satmar cafe where we had met so that he could tell me the story in the privacy of his car. This father and many other Satmars I reached out to were only willing to speak to me on condition of anonymity—scared to become the next outcast member of the Satmar community like Sam Kellner, for tattle-taling on other members of the community to anyone outside.

Moster’s provocative billboards have triggered some backlash in the Satmar community but he is thrilled that their slogans are generating conversation about the issues. Yet it annoys him that the leadership does not see his efforts as chesed. The strategy of Young Advocates for Fair Education, he said, is not to apply pressure on the Rebbe himself, but to reach government officials at the top, and constituents at the bottom to push to improve secular education within the Satmar schools.

Just like Moster, Deen, who managed to complete only one semester of community college, believes that opportunities for college or pre-professional programs will open when and only if Satmar boys are given adequate English preparation in school. If the status quo does not change, an uneducated new husband and father “has to sit with his wife to teach him how to just read basic words . . . so the potential [to enroll in college] does not exist.”

“has to sit with his wife to teach him how to just read basic words . . . so the potential [to enroll in college] does not exist.”

These modest educational opportunities feed into economic disadvantage when men lack the English skills to succeed in most professions, but also the computer skills required for the new technological jobs that are popping up. Moster said that the Hasidic communities in Borough Park and Williamsburg “rely more heavily on government assistance than Brownsville and Bed Stuy.” Everyone interviewed, both within and now outside the boundaries of the community, noted how adept Satmars were at working the system. But those wedded to the establishment, like the reporter/translator, point to the success stories that undergird the community, such as the family that owns and employs Satmars at B&H.

Poverty is far from a new issue for Satmar Williamsburg, with at least 33 percent of families there receiving public assistance by 1997. Colliding factors, including real estate hikes, high birth rates, and a lack of secular education or computer skills are making the problem more acute. A special 2011 report on poverty in eight New York counties declared Williamsburg the poorest Jewish area among them, at 55 percent poor and 17 percent near-poor Jewish households. The United Jewish Appeal’s report on Brooklyn Jewry also emphasized the massive population increases, noting that 50 percent of Jewish Williamsburg residents are under 18 and only 3 percent are over 65.

Satmar boys looking up at a helicopter passing by, while filling the street for celebrations related to a prominent Rabbi visiting from Israel. Photo Credit: Mark Hanover

Moster himself spent years working a dead-end job in a warehouse, as many young married Satmar men do. He said the community’s insularity helps residents share the secrets of maximizing government benefits. “Of course, a lot of it has to do with the fact that they’re very resourceful,” he said. ”if one person knows about the benefits you can get or the schtick you can do to get a certain benefit, and that’s where WhatsApp comes into play of course. Everyone gets that.”

Still, no one wants to be on welfare. The nutritionist sees two groups emerging financially in the community, the haves and the have nots. Half of the successful group, he said, “will flush it down as soon as they made it, because they have no organizational or financial skills.” Most of the community just goes paycheck to paycheck though, only surviving on government handouts. Without government funding, he said, the community “would have expired a long time ago.” In fact, government assistance makes much of the Satmar lifestyle possible for the poor, given the cost of kosher food, private tuition, and rising Williamsburg rents.

Deen accepts it as “a matter of course—people get married and they rely on government benefits, at least in the early years.” Katz, on the other hand, sees that the community is “going through serious convulsions—huge seismic shifts.” He sees very few middle class people anymore and blames this on the transition from industry to technology. Under the old system, the under-educated could eke out a living but technology requires skills many community members lack. Katz also wonders how the situation will evolve since his “brother’s six children will probably end up having six children of their own. How are they going to feed each other?”

“What does middle class mean when you have 12 kids?” was Deen’s rhetorical question.

“What does middle class mean when you have 12 kids?”

Deen was especially curious about the comfort I feel praying in Williamsburg, and the acceptance I feel praying in the basement haven. ”Maybe I’ll come another shabbos,” he said. He had followed that very same search for piety, or religious authenticity. I couldn’t help but compare our journeys as I listened to his recorded yiddish-isms on the train back to Williamsburg.

Once back home, I left my baby blue smartphone on my nightstand and ran through the snow to the mikvah and then to the basement synagogue to welcome the Sabbath. My garb had changed. I wore the black and silver patterned bekishe, the frock-coat designated for Sabbath and holidays, I had bought as a costume the previous month for the Jewish halloween-esque holiday of Purim. By no means did I fit in. Mine was an $18 polyester knockoff, with the pattern of a different Hasidic sect. It bore little semblance to the Satmar’s all black gorgeous silk bekishes that cost many hundreds of dollars. But I felt like royalty in my new robe.

Satmar teens during celebrations for a prominent Rabbi visiting from Israel. Photo Credit: Mark Hanover

Walking from services to the nutritionist’s apartment for a family Sabbath dinner, snowflakes were falling onto the tall fur streimels on the heads of those in our group of walkers and the hoards of other Satmars heading home to dinner. The south side of Williamsburg felt a lot like Satmar shtetl life back in Hungary a century ago. Across the street from the nutritionist’s apartment building a new luxury high-rise was going up, accentuating the neighborhood’s cultural divide.

We walked into his apartment, where the nutritionist’s wife was still praying and their four children were dressed up for the Sabbath, napping or playing quietly. All eyes lit up when their father walked in. Collectively, they jumped up to tell him about their week in school in Yiddish and received their traditional Sabbath blessings in Hebrew for the boys to be like Joseph’s sons Ephraim and Menashe and girls to be like foremothers Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah. I helped the youngest into his high-chair and his mother nudged her older children to introduce themselves in English. She started asking me about my bekishe and beard intentions once the children had all gotten into pajamas and been put to bed. ![]()