Print Is(n’t) Dead

Is print’s new wave fool’s gold or another golden age?

by Stephanie Eckardt

NOBODY CARES ABOUT YOUR OH-SO-COOL KICKSTARTED TACTILE MINIMALIST UNORIGINAL MAGAZINE.

That was the bold, all-caps message emblazoned across the 12th and latest issue of the print magazine Gym Class, which prompted a flurry of responses before it even found its way into readers’ hands. As it turns out, people do care—Gym Class itself is one of the very titles the cover line was poking fun at, and before its editors could reveal more than the cover, the limited edition issue sold out. The message resonated throughout the world of independent publishing, where, believe it or not, most everyone believes that print magazines are deep into their “golden age.”

Forget the Recession-era doomsayers. The score of editors and industry experts I interviewed about the ways they are filling the chasm left by yesterday’s print brontosauruses are resolutely positive about the future of print on paper. They are passionate in their determination to create something in their own right—and they are not in short supply. So many new titles have emerged in the past few years that competition among them is becoming a problem. In apartments and communal studio spaces that stretch from Brooklyn to London, their efforts to turn a new page for print are promising and innovative, but still in search of stability.

“We’ve gone through this process where magazines have really had to fight,” said Rob Alderson, editor-in-chief of the design-centric Printed Pages. He was talking about the beating print took when the Internet started pounding news magazines around 2005, and only got more lethal with the economic crisis that began in 2007. In this “golden age,” Alderson said, there has been “a lot of attention lavished onto independent titles.” Unlike earlier efforts, these “post-Internet print products” are not “trying to compete, stupidly, with the Internet.”

One of the first to see gold in the new start-ups was Jeremy Leslie, who has followed the industry closely for more than 25 years. He considers the new boom “self-evident” from the kinds of innovation he covers almost daily on his popular industry blog, magCulture. “From a creative point of view, I think there’s better stuff around than there ever has been,” Leslie said over Skype from his office in London, stockpiled with publications. “There’s no loss of appetite to make your own magazine. We get sent them here, and they just arrive and arrive and arrive.”

Yet he is cognizant that many people, even some within the industry, still need to be convinced that print is not on its deathbed. It is a point he has been arguing since 2003, when the precursor of his website, his book magCulture, came out. “The tide is just beginning to turn,” he said. “It’s a much sexier headline to hear something is being killed off by something, it’s a much better story. But nothing’s ever as simple as that.”

Nor is it a new story. Magazines were the most accessible form of home entertainment at the dawn of the 20th century. And despite predictions to the contrary with the ascent of radio in the 1920s and then television in the 1950s, popular general interest titles of the times survived and even thrived. Cosmopolitan, for example, then a general interest monthly, circulated to more than a million subscribers each month. Magazines even experienced another heyday in the television-rich 1960s when LIFE, which had been featuring its striking photography since 1936, was selling up to 13.5 million copies a week.

The “print is dead” cries sounded again in the 21st century as digital began its aggressive takeover, and the economy upended. That combination certainly hit the industry hard. Media conglomerates and corporations cut out hundreds of titles, downsizing and sticking with what was safe. Publishers shuttered so many magazines between 2008 and 2009 that Gawker catalogued each new announcement with the tag “Great Magazine Die-Off” and held polls asking which Condé Nast glossy should survive. By no means was this an exaggeration given that the media company eliminated four titles in a single day later in 2009, including the beloved Gourmet, a foodie bible since 1941.

True, a whole swath of print was dying—especially newspapers, news magazines built around summary and analysis of the week’s breaking stories, and major mags that relied heavily on advertisers. Yet while more and more mainstream titles fell into that already bloodied arena, they made room for the indies to take off. The new crop, however, has no designs on becoming a Condé Nast. Many do not even plan to be lucrative. These are passion projects, the work of designers, writers, and journalists who are using their devotion to this tactile platform to create communities or be the go-to voice for niche topics. Instead of advertisers, they rely on sponsors, crowdfunding, and side brands to simply break even.

Ironically enough, print’s oft-cited nemeses—technology and the Internet—turn out to be “a key engine to the success of most the independent magazines,” Leslie explained. For some, like the popular Australian title Offscreen, it is even at the center of their subject matter. The new breed sources material from the Internet, collaborates via email and social media, and finds the design and printing resources they need online to make their ideas tangible. A novice can readily watch design tutorials on YouTube, make layouts on Adobe Creative Suite, and get funding on Kickstarter. The contrast in accessibility is stark from even just 10 years ago, when just to locate an image would mean a long slog through phone calls, mail orders, transparencies, and scanners. Not to mention the huge expense.

“It’s not a Luddite movement,” Max Schumann assured me. He is the acting director of Printed Matter, a store in Chelsea that offers a selection of more than 15,000 periodicals. “The new generation of publishers is very much exploiting and using the things that technology has to offer.”

The Internet has also fostered a virtual community for these indie publishers. Facebook groups serve as forums for editors to combine resources and overcome common hurdles, such as finding the best distributors. Just a few months ago, the British design agency Human After All created The Publishing Playbook, a free, shared folder of resources on Google Drive that instructs its users in how to make a magazine. It offers business models, yearly publishing schedules, subscriber matrixes, not to mention the titular Playbook itself—a 49-page guide that breaks down everything from finding a concept to committing to the long haul.

Andrew Losowsky is a magazine expert, magCulture contributor, and project lead of The Coral Project. Those who choose to create and invest in print today, he said, have to be committed and “have a sense of ‘why am I doing this in print, rather than anything else.’” Printing technology may have become cheaper, but that does not mean it is cheap. Shipping and paper costs can only get so low, and there is no denying the price difference between a blog or an active Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter or Instagram account and, say, a 150-page hardback of thick paper stock like the Parisian biannual Self Service. “And so when it becomes a conscious choice and not a default,” he added, “that forces the quality of print to get better.”

That is not to say the new social media platforms have no part. Social media blasts, dedicated websites and e-mailed newsletters have eased at least some of the difficulties that have always come with trying to promote a print magazine and sell it widely. “The reach is much more, the ability to get money from small groups is much easier, to collaborate, to hear different voices, to reach out,” Losowsky said. “All these things make it an incredibly exciting time.”

So when did this boom start? Although it’s been most apparent in the last five years, and Alderson dates it back two or three years, Leslie saw signs as early as a decade ago. Actually, Leslie said, interest in self-styled magazines really took off 15 years ago, but the economic recession caused a significant disruption. Several titles that served as examples for today’s crop, like Apartamento, a biannual on living spaces and interiors, launched around 2009. Yes, the same years as the mainstream “die-offs.” It is no coincidence that many editors cite these magazines as their initial sources of inspirations. They had the sophisticated, well-defined concepts required to weather the recession.

So when did this boom start? Although it’s been most apparent in the last five years, and Alderson dates it back two or three years, Leslie saw signs as early as a decade ago. Actually, Leslie said, interest in self-styled magazines really took off 15 years ago, but the economic recession caused a significant disruption. Several titles that served as examples for today’s crop, like Apartamento, a biannual on living spaces and interiors, launched around 2009. Yes, the same years as the mainstream “die-offs.” It is no coincidence that many editors cite these magazines as their initial sources of inspirations. They had the sophisticated, well-defined concepts required to weather the recession.

At the same time, especially in Europe, sleek reimagined magazine stores popped up. The art world took note in particular with the 2008 opening in Berlin of Do You Read Me?! The store combined the stock of New York’s storied newsstands with refined, European design. The trend was visible enough by 2012 for Klaus Biesenbach, cultural tastemaker and chief curator of the Museum of Modern Art, to encourage his staff to do something similar. The museum opened up ArtBook @ MoMA PS1 that same year with 200 independent and mainstream titles and New York Magazine quickly named it the city’s best magazine store. It is independent of the Long Island City museum but located inside its modernistic concrete entrance. ArtBook’s manager, Julie Ok, expects to stock 500 titles this year.

Carting a dolly stacked with her favorite magazines to share, Ok led me past the rows and tables of publications that greet visitors on their way to purchase entry tickets and into the museum’s courtyard. Every fall, this outdoor space hosts Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair, an ever-expanding zine and magazine festival that has been called the publishing world’s Coachella. Its most recent events in New York and LA each drew more than 30,000 guests.

Ok is not blindly optimistic about the the future of the print medium. She recognizes that newspapers and mainstream magazines “are shutting down all the time. But I think that’s part of why there is this resurgence of independent publishing,” she said. “People are finding that the magazines that they want to read don’t exist, and what better reason to start a magazine yourself than to make the magazine that you want to read?

“That’s what I see when artists and creative people in New York come together and bring me their first issue of their magazine. It’s because they’re either part of a community or seeking a community and they want to put out this thing that has their voice.” Indeed, editors regularly visit the store on foot, laden with dozens of copies of their own first issues. Ok will carry at least a few on consignment, seeing the store as “a jumping off point for a lot of local magazines.”

After the success of ArtBook’s launch, the shop added a hundred new titles the next year and a hundred more the year after that. Now the rotating inventory hovers around 400. The selection varies from niche titles for magazine enthusiasts, established independents like Cabinet and Aperture, to a few staples like Time and Harper’s for tourists who stop off at PS1 on their way to New York’s airports. The independents are her best sellers, she said, and account for about half the stock.

Ok purchases wholesale from independent publishers, paying them 50 percent of each title’s retail price. About half of them come from distributors who act as middlemen between publishers and retailers. The store has built relationships with those such as Idea Books and Motto Distribution, and Ok hopes to work with others that exclusively carry independent publishers, such as Antenne Books in the UK. Distributors make it easier for Ok to nab 20 or so titles at once and that consolidation eliminates the need to make individual contact with about half the magazines ArtBook stocks. It also helps keep track of titles that publish on such varying, often unreliable schedules. The other half of the inventory comes from titles that can’t afford distributors. Ok communicates directly with the staffs of those publications.

For the “passion projects,” Ok’s consignment system works for both the store and the small magazine owners. The publishers get prestige visibility for their magazines and Ok pays them only if they sell. Printed Matter, the Chelsea store with 15,000 publications, has a similar system for the zines that comprise most of its inventory, although it reduced the number of submissions it accepts by two-thirds after its open policy caused a deluge. Ok carries almost strictly magazines, which she defines as serial periodicals, rather than one-off artist books or pamphlets.

The number of copies Ok stocks depends on the magazine’s frequency of publication and its price, but she generally aims for four to six. That range that may sound low, but the store has space constraints and carries back issues, too. Some copies she can predict will sell well. For example, she ordered a larger quantity of the popular British magazine The Gentlewoman’s Björk spring/summer cover, as it coincided with the singer’s MoMA retrospective. The magazine’s Beyoncé cover sold 30 copies in the weekend of the New York Art Book Fair alone. She also always orders a carton, or about 35 issues, of contemporary artist Maurizio Cattelan’s Toilet Paper, the back issues of which can fetch up to 10 times the cover price. Toilet Paper is also distributed by ArtBook’s sister company, Distributed Art Publishers.

The store’s overall best sellers are mostly what the magazine guru Jeremy Leslie calls a new hybrid, “neither independent or mainstream.” These titles are still technically independent and maintain their editorial creativity, but they have become so successful in the public sphere that Whole Foods will stock them. They have even found a home in the “Collectible Magazines” section of Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop.

At their forefront are Kinfolk and Cereal, two titles with pared down editorial design that play up white space and a spare aesthetic, attracting the wealthier demographic that is interested in “slow living.” Their typological aesthetic has spawned a rash of “rampant conformism” from other new magazines. There is even a blog called The Kinspiracy that collects Instagrams of the magazine on thousands of coffee tables, posed next to lattes and halved citrus fruits. Ok said a store patron recently inspected a handful of Kinfolk-type publications and, sensing something deeper afoot, asked, “What are these?”

A sample grouping of Kinfolks from the blog The Kinspiracy.

Apartamento has been another independent mainstay in this vein since 2008, as has Fantastic Man, a men’s semi-annual publication since 2005 with a definitive cover aesthetic. It’s also connected to The Gentlewoman, a biannual launched in 2010 and a fellow bestseller. Along with these trendsetters are newer titles like Hello Mr., a small-scale biannual since 2013 that bills itself as a community for gay men. Ok said a customer recently came in expressly to buy it, saying the mag changed his life. Still others ride the wagon of the slow food movement. Among them are Lucky Peach, Momofuku chef David Chang’s quarterly since 2011; The Gourmand, a three-year-old British food and culture biannual, and Gather Journal, an American recipe-driven biannual, which also publishing in 2012.

While ArtBook is financially independent of MoMA, the museum’s foot traffic is key to its success. Yet Ok said more and more customers come to Long Island City just for the magazine store, something Ok knows from talking with patrons and from watching them as they come in straight from the street, make their purchases, and head back out the doors. The operation remains almost entirely brick and mortar with limited online sales from the store’s website.

To find new titles and stay on top of developments in the field, Ok relies on an arsenal of online resources. There is the weekly print-centric podcast by British magazine empire Monocle, a global affairs title started in 2007 that now even has international cafés; blogs like Leslie’s magCulture, and Instagram accounts for sites that are almost effective enough to act as design databases: Cover Junkie and Steve Watson’s Stack.

Stack was designed for people without access to stores like Artbook. Through its subscription service, it gives readers the chance to browse by sending out a new, surprise title each month. Subscribers pay a flat rate of about £60 a year, or £5 pounds for each mag. Since Stack started in December of 2008, Watson has not had to repeat a single title, nor does it appear he will have to any time soon.

“I’m literally drowning in magazines here,” he said over Skype from his flat in West London, Stack’s home base for the time being. He is planning to hire help for the first time next year. It may be Stack’s growing reputation that has brought so many new magazines via inbox or Royal Mail, “but it definitely feels like there are more things coming out,” he said. That is as good a thing as it is a worrisome one, he said. “It increases competition between these magazines.”

Like so many of the titles Stack distributes, his operation started as a dream that found footing through weekends and weeknights of after-hours dedication. As the magazine world moved faster and the project ate up more and more of Watson’s work week, it came time to sort out finances and logistics. He upped his prices and efficiencies so that in 2014 he could quit his day job as editorial director of Human After All, the creative agency that just put out The Publishing Playbook.

What started as a hobby almost seven years ago is now his full-time gig. He blogs weekly interviews, runs a video review series, organizes regular panels in London and across the globe, teaches publishing courses through The Guardian, posts weekly Instagram covers, and of course, assesses the dozens of publications he receives each month, selecting the worthiest to send out to his 3,100 subscribers.

When asked about the discourse on print going wayward, he shook his head no. After a gulp of Cup o’ Noodles—he was too busy to squeeze in a real lunch—he said, “Actually, I don’t think that many people are saying that anymore.” At least, there are fewer than there used to be. Still, “there’s no denying the fact that print as an industry is in decline—of course it is,” he conceded. But “when you look at the small independents, that’s where you see some really exciting creativity.”

Watson’s aim with Stack is to make these magazines easier to discover and cheaper to buy. The low monthly subscriber fee means that many publications get to readers for up 60 percent off the cover price. Although Watson often receives requests from subscribers for magazines that focus on specific topics, he said he prefers not to know his readers’ preferences. He chooses publications based on the quality of the design and the editorial content so that even a niche topic way outside a subscriber’s usual interests will be enjoyable.

Titles have included the crowd favorites already mentioned—Cereal, Offscreen, and Printed Pages—but also publications with less established followings. For example, Victory Journal is a sports magazine with enormous pages that showcase remarkable photography. Boat is a travel biannual whose editors move briefly to the location they cover in each issue.

Stack kicked off with Watson asking editors: What are the problems that you have as an independent publisher, and how could a different method of distribution help? Perhaps that is why Stack has been so successful for Watson. His mailing list keeps growing, with 500 new subscribers this year alone. It was built from the ground up around the problems print producers face, and came from years of experience writing for magazines that were “used to never having any budget.”

His editorial background also taught him not to rely on advertisers, which often requires massive amounts of traffic and dissemination to yield any real returns. “I’m much happier with the idea that every single subscriber I have, every single thing I send out, I make a couple of pounds from that subscriber,” Watson said. Given the interest from customers, “that’s a really stable business.”

Less than an hour tube ride from Watson’s flat are the North London offices of the prominent British design website It’s Nice That and its accompanying magazine, Printed Pages, which has grown into a major presence among the independents.

Less than an hour tube ride from Watson’s flat are the North London offices of the prominent British design website It’s Nice That and its accompanying magazine, Printed Pages, which has grown into a major presence among the independents.

In 2009, editor-in-chief Rob Alderson and his cofounders started putting out what amounted to little more than a print version of It’s Nice That, which they launched two years earlier. After two more years and eight issues, things seemed to be working out. But as a showcase for design, it was clear it could make a better use of the print medium. So they took the year of 2012 to regroup and think hard about what Alderson calls a series of vital questions for today’s publishers: “Why are you telling this story in print? How are you telling that story, and how are you harnessing the opportunities that print has and the advantages that print has over online?”

Print’s allure is hard to articulate beyond the joy that comes from holding a physical object in your hands, flipping through it; even smelling it. These reasons are cited often enough to have become a source of parody, most famously in a McSweeney’s piece in which the protagonist’s obsession with print escalates into a full-on page-sniffing addiction. But Alderson and his team were determined to figure out that “visceral, very human reaction” behind their passion for the medium, and nail down why print was still “worth doing” despite the time, risk and cost involved.

They found that beyond the olfactory experience, the act of flipping through pages allows readers to discover articles and images that otherwise would have escaped their attention, items they would have missed or ignored online, or that algorithms would have prevented them from seeing in the first place. As this serendipitous style of reading becomes increasingly rare, Alderson wanted to aim for “wrong-footing people, or surprising them.”

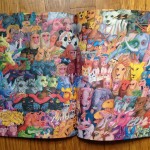

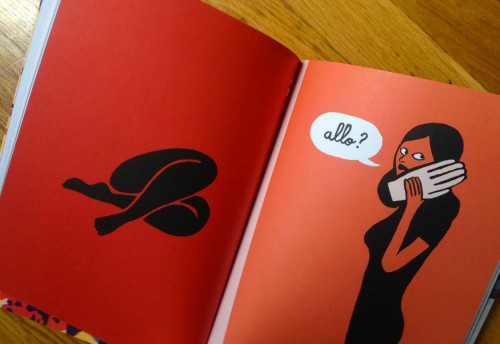

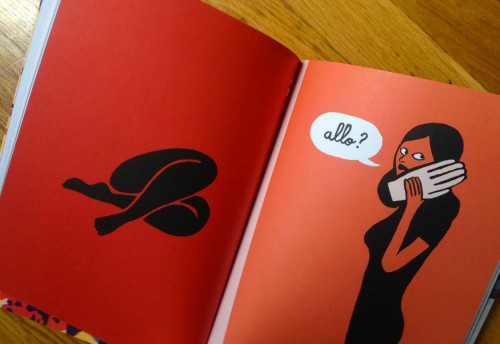

The It’s Nice That staff spent hours in magazine stores, poring endlessly over other publications, and came up with two other discoveries. First, most of the independent titles looked the same, following the minimalist design aesthetic of the decade-long leader, Fantastic Man. Its portraiture and simple fonts are precisely what the Gym Class cover text was mocking. So quite deliberately, the It’s Nice That team made bright, illustrated covers for the first four issues of Printed Pages in an effort to stand apart. The inside pages have their fair share of conventional white space and striking photographs, but there are also full-page spreads drenched in scarlet and highlighter yellow ink with only one or two illustrations at their center.

A spread from the Winter 2014 issue of Printed Pages, featuring graphics by Saul Bass (left) and Jean Jullien (right).

As the number of new titles has exploded, so has their price point. Many go for £10 to £20, far too much even for print devotees like Alderson and his team. As they reimagined Printed Pages, they built its economic model around a steady £4 per issue, although that jumped to £6 since when the magazine went biannual this year. The plan worked. The redesign, released initially with 6,000 copies, succeeded as a self-sustaining, expanding brand for their website. The online reach of It’s Nice That is now 300,000 visitors a month, but Alderson, who oversees the company’s editorial content, said that the it is the magazine that is generating the most useful publicity. Most of the requests he receives for interviews and speeches are about the magazine, not the design site.

Alderson still works online as well, keeping up with what is happening and what is quality in design as he and his team see up to 60 new projects a day. Online/print is not an either/or but an awareness that magazine makers must have to deepen their own content and differentiate themselves from competitors in the Internet’s endless “editorial river.”

“There’s a shift now in print to say, “Let’s slow this down, let’s do something more considered and encapsulate what print is good at,” Alderson said, “but let’s do it less frequently.” In the switch from four issues a year to two, Printed Pages joined other major magazines such as Dazed, which went from monthly to seasonal, and New York, which went from weekly biweekly, both in the last year. Even successful indies such as Port and Wilder have spaced out their issues.

Leslie, the magCulture writer, agreed. “There’s a move towards accepting that digital and print has to work together,” he said. Print still is at the center of most publishing brands, but instead of letting it commodify further and become cheaper and poorer quality, people are investing in quality. And so while editors might publish less often, he said, “they’ll make it more worthwhile when they do.”

Of course, there’s another reason for magazines to publish less frequently: producing fewer issues costs less. While Printed Pages and distribution systems like Stack and ArtBook are built on stable and even lucrative business models, the financial operations of most smaller titles can be shocking. Creating a magazine may be easier and cheaper than ever, but by no means does that mean cheap. “One-man magazines” and those with extremely small staffs were not built around the idea of being long-lasting or even profitable. The challenge is first to see if a passion project can actually make it to ink and paper. Figuring out finances and logistics too often come later.

So many magazines today would have died years ago if “left to the cruel commercial winds,” Steve Watson said, but they have survived thanks to sheer passion or rich relatives and connections. From what Watson has seen, “often when a magazine ceased publishing, it’s not just because they’ve run out of money,” but because “it stopped being exciting after spending two years of literally every waking moment either doing your 9-to-5 or doing this thing. It can grind you down.”

Although most magazine staffs are doing what they do out of love for the medium, their job often is grueling. Those I interviewed started out extremely positive with choruses of praise for the new “golden age,” but they almost inevitably darkened halfway through when the conversation turned to finance and distribution methods.

For many would-be publishers in this field, crowdfunding has been a godsend. It is de facto that most new titles launch with Kickstarter. In return, most editors send supporters a copy of the publication’s first issue, which also guarantees the makers a source of exposure and potential subscribers. Some campaigns return even more gains than the amount of the initial request. The quarterly Makeshift, for example, wound up with over $40,000 when its publishers asked for $15,000.

HRDCVR, a hardback magazine set to launch this summer, got $67,000 in response to its $30,000 appeal. The funding was actually a second attempt to find backing on Kickstarter. An earlier three-week campaign without the requisite great video looked as if it would fail, so the married co-founders Elliott Wilson and Danyel Smith shut it down and put up another within an hour that emphasized treating every backer as an individual.

Some 70 percent of HRDCVR’s funders were new to Kickstarter, meaning they had signed up specifically to support the project. As thanks, Wilson and Smith tweeted individual shoutouts with the hashtag “#NewBackerAlert.” They also printed every one of their 500-plus names in the print issue.

Obviously appealing to backers was the project’s intent. HRDCVR will seek to serve “the new everyone,” or minorities who make up most of America. Smith and Wilson know from decades of working in the industry, at titles such as Vibe and XXL, that the outlets that do exist are too often poorly funded to be quality products. “Frankly, I feel like there isn’t a lot of beauty out there for the underserved,” Smith said. Part of their move to create a hardback was for “people to have something that they can kind of treasure.”

The HRDCVR team is diverse itself, and definitely far-flung. Unpaid interns stretch from Austin to Seattle to Brooklyn, and contributors are international. Its core group includes a number of colleagues from Smith’s recent journalism fellowship at Stanford. Seven are based in New York with Smith and Wilson, but only a few can fit in the small glass-walled cubicle they rent in a communal studio near the Manhattan Bridge. They tend to work from Brooklyn Roasting Company, a lofty coffee shop around the corner that Smith affectionately calls the “satellite office.” Most often, they turn to “email, Basecamp, Facetime, Skype,” Smith listed. “Usually conference calls are tools of the trade,” but at HRDCVR, “it’s our main thing.”

With the crowd funds, they have been working on finishing the launch issue, the release of which keeps being postponed. Then will come getting it out there with as many free copies as they can afford to print. Rather than thinking of distribution, Smith and Wilson, who have spent decades at major titles such as Vibe and XXL, are savoring not having to cater to companies, newsstands, and subscribers. Smith has faith there will be enough interest from minorities, or at least from her hundreds of thousands of Tumblr followers, to finance the coming issues. Yet the lack of a solid financial plan for after the launch is worrisome for the publication’s longer term prospects.

Crowdfunding then, has two faces. It lets a big idea come to life, but also enables its publishers to put off planning for long-term financial stability. Stack’s Steve Watson prodded Alec Dudson to address that issue before he launched a Kickstarter campaign for Intern. When Watson pressed Dudson as to how many issues he foresaw printing, Dudson told him that honestly, he would be happy if he could get out even a single issue. Watson shot back, “Look, if you plan like that now, ‘if I get one out,’ you’ll only ever get one out.”

Intern‘s Kickstarter ended up bringing in almost two thousand more pounds than Dudson had asked for. Although the timing was coincidental, his magazine was seen as a “counter-culture response” to the game-changing court case for interns’ rights just the week before Dudson’s campaign. With some of his new funds, he sent his 347 backers a newspaper format “issue zero” as a prototype. Its goal was to feature the work of talented interns, shock readers with its quality, and continue the conversation about unpaid labor. Another magazine to use its crowdfunds for a newspaper prototype was the Australia-based Four & Sons. Its publishers aimed to prove their “dog-centric” biannual was not a joke. With stunning photos and contributors like Daniel Johnston and Bruce Weber, it is definitely no Catster.

-

Four & Sons

Yet the financial situations of both Intern and Four & Sons are precarious. Overhead is low with extremely small staffs, for the most part founders and their freelance contributors. But that also means less hands on deck to stay on a regular publication schedule. Personal sacrifice often stands in for a clear business plan. Dudson resorted to sleeping on his brother’s couch for months before a bequest from his late grandmother afforded him a rent-free home. And yet he still struggles to support himself, opting instead to ensure a fair freelance rate for his contributors. He went into the project knowing it was “never going to be a money spinner.”

With no inheritance as a fallback, the editor-in-chief of Four & Sons, Marta Roca, instead relies on handouts. Everyone involved with the publication pulls contacts and asks favors, too, “which I guess is maybe part of the indie publishing culture,” she said. “Everyone understands that this is how things are, that everyone’s doing this for love and no one ever has any money to put toward anything. So if you are very honest and you explain that to people from the start, people are really generous. That was actually quite a nice thing to realize.”

Granted, both of these titles are only two issues old. Dudson’s third issue has been delayed for months as he deals with various setbacks that would have been minor if he were not his only employee. On top of that, a faulty email account impeded efforts to contact sponsors, slowing progress further.

Roca has the help of a small team, and although they made their share of “rookie mistakes” in the crossover from digital to print, the third issue is still on schedule for this summer. It helped with stability that they decided to run the publication as a website for a year before moving to print. The crossover has proved to be a “reassuring exercise,” she said, and there has been “overwhelming support” from both Australia and the United States.

There are success stories. The most stable indie publishers plan ahead, forecast, and budget. But they also find alternative revenue streams in advertising and design agencies, advising corporate magazines, and running events.

There are success stories. The most stable indie publishers plan ahead, forecast, and budget. But they also find alternative revenue streams in advertising and design agencies, advising corporate magazines, and running events.

As a business, “a magazine is just not sustainable in its traditional format and approach,” said David Hershkovits, co-editor-in-chief of Paper magazine, now known for its recent covers with Kim Kardashian’s derrière but also an independent title since 1984. Like many experienced editors, Hershkovits firmly believes that a magazine today cannot just be a magazine—or at least, it would be very difficult. It needs instead to be a diverse platform. He likened his industry to couture, where brands are built on a myriad of money-making licenses for everything from perfumes to scarves to tiered lines of ready-to-wear. The highly skilled, extremely time-consuming work of couture itself may be a money-loser, but it is essential to the brand and therefore the strength of a company.

The work involved in producing a magazine is no less exacting. “It’s so expensive and requires so much detail,” Hershkovits said. “People work on it as if they were sewing these threads day and night, with editors reading the stories a million times finding misplaced commas. It’s really, really intensive work.”

Paper’s perseverance could be a useful history lesson for the new crop of editors, as its beginnings are almost eerily similar to those of many of today’s titles. Hershkovits and Kim Hastreiter decided to launch their own publication on the niche subject of the downtown New York scene after the one where they worked, the storied SoHo Weekly News, shuttered in an earlier economic downturn. With naïve optimism and practically no business experience, they launched on the largesse of friends, who wrote for them for free.

Yet they have weathered the past three-plus decades without having to close or sell out to a media conglomerate. From the start, Paper was known as much for its publication as for its downtown parties, which was great for name recognition with its target audience. Paper has been an early adopter since the start. It had a website as early as 1996, and a YouTube account when the site first started. Today, it runs an event series and a creative agency, Extra Extra, to help pay the bills.

In the past, Paper’s team has gotten over economic hurdles by laying low and cutting back circulation. But the latest recession helped them realize that much of what they were doing had applications outside of the magazine. The print product was, in effect, no longer the end product. The Kim Kardashian cover was part of an initiative called “Break the Internet,” and it drew over five million unique visitors to its website in just over a day. Hershkovits is now even thinking TV.

The best example of a 21st century success may be Kinfolk. In addition to its popularity, it has two stable sources of income: a partnership with the furniture brand West Elm, and an international monthly event series of dinners and workshops. For most magazines, investing in promotion can be a profit-killer, with the cost of prominent shelf space sometimes more than the realized profit from sales. But because of its multiple revenue streams, Kinfolk can afford to pay for prime placement in places like Barnes & Noble and still come out ahead.

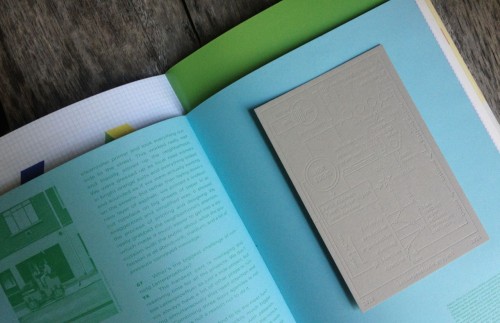

Kinfolk was even for sale in the coffee shop where I met with Elana Schlenker, near her design studio in a Greenpoint rental which she shares with a small clothing line. Both the studio and her magazine, Gratuitous Type, are spaces for her to work on graphic design, which has been her primary means of self-support since late 2013. Schlenker missed the joy of running a magazine that she started in college, so she took her savings and created what she calls “a pamphlet of typographic smut” in 2011 with no plan or idea if it had the legs to be a serialized project.

It took on a life of itself as an almost promotional portfolio of her skills. Unintentionally, she was working from a recently revived industry model: design studios publishing magazines. Some of the previously mentioned titles are also studio-run, advertising-allergic operations: Brooklyn creative agency Doubleday & Cartwright puts out Victory Journal, and Human After All puts out Weapons of Reason.

Gratuitous Type has pricey features, such as the fourth issue’s clear dust jacket silkscreened with gold polka dots and its removable insert of embossed cardstock. Schlenker has found them to be worthy investments, as they draw in clients. “It’s not lucrative,” she said, “but it brings in enough work that it feels like it totally makes sense for me.”

Schlenker was almost upset when the 1,000-copy run of her third issue sold out. Her plan had been to have copies available to show at the Publications and Multiples Fair in Baltimore. She doubled the run of the most recent issue, but within a couple of months, there was not enough stock left to warrant a table at PS1’s New York Art Book Fair. The next issue will have 4,000 copies and she thinks she is “poised” to do more than break even. It will also launch her new supplement, Further Reading, which is just what it sounds like.

Her design work provides steady enough income to make the wait for payment from from her European distributor, Antenne Books, less of a hardship. “It doesn’t bug me that much. It’s actually nice because it’s like, ‘Oh I forgot there was money,’” she admitted. Antenne allows her to price and choose where she is carried internationally, and she takes care of U.S. distribution on her own. “The business side is important in that it’s not a money pit, but it’s not something where I have staff I have to pay.” So Gratuitous Type can continue being ad-free, though Schlenker is interested in working with sponsors if she can ever find the time.

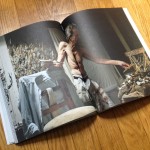

Alyse Archer-Coité is another Brooklyn-based woman who runs a title almost entirely on her own. She is editor-in-chief and the force behind MAKER, an ink-drenched tome of several hundred pages of personal, undisplayed artwork, such as watercolors by the director Gus Van Sant. To launch in 2012, she invested the $10,000 she inherited from her late grandmother, an amount that her mother matched. With a $40,000 salary at her day job, she lost money on the first issue, especially as she gave away many of the 1,000 copies.

The second issue lost money, too. She paid for that one entirely by herself. Part of the loss was thanks to a deal with The Standard, a chic hotel chain that agreed to put copies of MAKER in the rooms of its New York guests. It guaranteed exposure to the exact audience she wanted to reach, but it also meant that she was giving away about a quarter of the run of 2,000 copies, magazines that would have retailed for $25 apiece. With each copy weighing about two pounds, distribution was a sweaty one-woman nightmare. Archer-Coité would load up her bike with a 40-pound stack and ride from Brooklyn to stores all around Manhattan.

MAKER now has an international distributor and is printed just once a year. It has found its niche as essentially an art catalogue, and Archer-Coité aims to do only five issues in total, which she appropriately calls “volumes.” The cap is not a concession, but a realistic embrace of the magazine’s book-like quality, as it now pushes 400 pages. It also creates more time to devote to MAKER’s burgeoning creative consultancy, whose clients include Pepsi and Absolut.

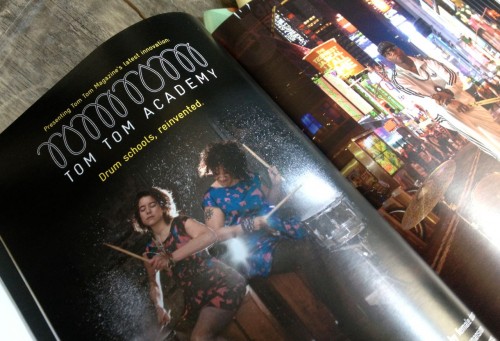

The same happened to Mindy Seegal Abovitz after she launched Tom Tom, her quarterly about female drummers in 2010. Her inspiration was a series of Google searches that yielded only sexist and degrading articles about women who play the drums. She has since created a variety of revenue streams, many of which double as community-builders. Her strategy has worked. At $6 a copy, Tom Tom has the most accessible price point of the newer indie mags I came across. She has worked with advertisers to stock it in Barnes & Noble and Guitar Center.

More importantly, from Tom Tom has come the drumming school Tom Tom Academy, which opened in Brooklyn last year. Tom Tom TV now has almost half a million views. Print is still dear to Abovitz, but more and more, these platforms are claiming her time. To build out even further, she is considering passing on her title of editor-in-chief.

Going multi-platform is also the goal of Carroll Bogert, Deputy Executive Editor of External Relations at Human Rights Watch. Last summer, she launched Human, the nonprofit’s print-only magazine. Her reasoning: “If I hand you a Human Rights Watch report it’ll be like, okay, now I have to eat my spinach. But if I hand you a magazine, you’d be like ooh, a magazine! Let’s see, what’s here? Pictures! People just feel differently about it.”

The nonprofit works with some of the best photojournalists around, and Bogert aims to showcase their work. Striking full-page spreads of armed child soldiers and a crowd gathered around a burning corpse have proved worth more than a thousand words. They have led individual donors to back upcoming issues when offered the opportunity to choose what photos will be featured next. When we met in her office on the the 35th floor of the Empire State Building, Bogert was still glowing from a meeting with a supporter only an hour earlier had interrupted their chat with an offhand aside: “You know I just love that magazine you’re doing, and I’d like to give you $25,000 to do another one.”

Below two proudly hung Peabody Awards and a famed war correspondent’s typewriter are Bogert’s filing cabinets, which contain notes starting in September 2013 from a series of meetings with magazine directors of other NGOs, including the ACLU, the National Resources Defense Council, the Human Rights Campaign, Oxfam, and Amnesty International. These groups are expanding and redesigning their print publications, convinced that four-color glossies remain an effective format to convey their accomplishments.

Take the Human Rights Campaign’s Equality, now the largest circulated LGBT-related magazine in the country. It reaches 300,000 people and adds more pages each quarter to accommodate advertiser interest. Big supporters such as Microsoft and American Airlines now cover Equality’s costs and are even obliged to meet HRC’s “yearly equality index” standard. Under this requirement, advertisers must adopt a long list of non-discrimination policies and support systems for the LGBT community. Alongside the ads are political analyses, profiles of those who have faced job discrimination, and even interviews with celebrities like Ava Duvernay.

Oxfam’s Closeup just rebranded and upped its output from three to four times a year after its consulting firm reversed an earlier recommendation to dump print altogether. The firm concluded that the magazine was the No. 1 factor in sustaining Oxfam member loyalty.

Like alumni mags, NGO titles are usually run by fundraising departments: “both their bane and their salvation,” Bogert said, as they have lackluster content but noteworthy funding and readerships. She sought to make Human an exception, pooling contributors from the group’s communications department. Her writers are field officers whose hard-hitting journalism creates a more oblique way to promote the organization and its achievements. The second issue features stories by such well-known writers as Evan Osnos, Nazila Fathi, and Jon Lee Anderson.

“Tragedy-based” subject matter makes advertising an unlikely source of revenue for Human. Print has yet to sway the nonprofit’s development office to send out Human to its mailing list. Bogert has had to turn to her own media contacts, many cultivated during her time as communication director and earlier during the more than 10 years she spent as a foreign correspondent for Newsweek. Though Human‘s quality is assured, it has yet to make it before the eyes of many readers.

Distribution, Steve Watson of Stack has said, is the next frontier for the golden agers. It is logical to think that online distribution would be the economical solution but no one has yet developed a model that works well. Yet the current standard of covers, price listings, and buy buttons does not seem to work, and iPad editions have largely failed to draw in buyers.

Distribution, Steve Watson of Stack has said, is the next frontier for the golden agers. It is logical to think that online distribution would be the economical solution but no one has yet developed a model that works well. Yet the current standard of covers, price listings, and buy buttons does not seem to work, and iPad editions have largely failed to draw in buyers.

It seems inconceivable that corporate-run monthlies like Parents still turn a profit with subscriptions at less than $10 a year per subscription. These titles create unrealistic expectations for how much a magazine should cost. As Hershkovits explained, this is because the structures that exist around magazines have barely changed for decades, when companies like Condé Nast buckled down on practices that would put their smaller competitors out of business. They started with subsidizing cover prices with advertising, reaching as many as they could in order to get more ad gains. But those artificial prices need to be adjusted now that print ad revenue is dwindling.

A print lover with a background in business, Celestine Maddy is a rare bird in the industry. She hated her job at an ad agency as a digital brand strategist before she left to start the gardening- and food-centered Wilder Quarterly in the fall of 2011, which has grown from 1,100 copies to 11,000. She was inspired by the bespoke quality of Apartamento, and the 31-year-old grit of Paper, where she used to be circulation director. While she agrees about the golden age, she finds most editors short-sighted of the fact that “magazines are an unsustainable business.”

Even if a magazine is vertically integrated, she said, “I would also say that you’re still going to fail.” As examples, she noted that Paper still struggles to make a sizeable profit, and Modern Farmer almost went out of business in late 2014 despite its steady readership and investments in the millions.

The big legacy corporations also work with a faulty distribution model. Only three distributors are left at the top of the game since Time Inc.’s Source Interlink closed last year, and they are “running a very, very, very old system,” she said. Key to all of their practices is destroying the very products they create. The covers of unsold copies are ripped off and mailed back to the publishers. Often the majority sit in warehouses and are eventually pulped.

The inefficiencies of the U.S. postal service also make Maddy skeptical that anyone will succeed at the magazine game, since everyone is reliant on this big black hole of costs: Bigwigs, indie-centric distributors like Antenne, and self-distributed titles alike have no choice.

Circulation is no longer even in Paper’s top priorities, which are now more digitally oriented. Paper cut out much of its worldwide stockage when the economy last cratered. Seeing themselves in places like Saudi Arabia was a “a lot of ego,” “but the cost was just unnecessary and didn’t really bring anything back,” Hershkovits said. “So we just cut that out.”

“You’re never going to get paid or make any money with distribution, unless you sell it yourself directly to the person,” Hershkovits said. Paper is carried by one of the major distributors, Curtis, and it was only in the last year that Hershkovits fully grasped the advantages of self-distribution. His team was well-prepared for the media hoopla from its Kim Kardashian covers, but did not anticipate the problems the cover would bring. Newsstands did not want to carry or display the cover, and it was too risqué to be shipped by U.S. mail. So Paper put it on its website and sold it directly through an online shop. Without cuts to the distributor, store placement, and even shipping and trucking to a certain extent, readers’ money went almost entirely to the company.

With major distributors, as Hershkovits pointed out, payment sometimes never comes at all. “You’re not big enough to audit and do all those legal things to make sure you do get paid, and they know that. And even if you do, by the time you get your five percent of the cover price or whatever, it’s so little that it doesn’t really add up to very much. So it’s a very terrible model that was built by the big magazines to keep the little people out. So they would lose.”

For Maddy, the only way the little guys can hope to survive is if someone completely reimagines the distribution system, or if they band together and form a coalition to streamline their costs. She herself was part of a Brooklyn-based attempt at the latter called the Little Magazines Coalition. Indie mag editors wanted to band together and sell ads across their titles, but their efforts eventually dwindled. All the editors were too focused on the daily logistics of their own publications, which were too different to really be of help to each other. But, she said, “it was a good thought.”

Schlenker of Gratuitous Type was skeptical, wondering if that would just recreate the Condé Nast-style conglomerate the indies want to avoid. Yet most editors were definitely interested when I raised the idea of a coalition to them. Many are part of Facebook groups that serve as forums for overcoming these hurdles.

Kai Brach started one of the strongest of such indie publisher groups, The Indie Publisher Club. He is also famously transparent with his operations of Offscreen, his three-year-old mag about people who use the Internet. He once ran an experiment that allowed readers to pay whatever they liked for the magazine for a week-long period, with a sliding scale that informed how much money he would lose if they only offered that price, and what they would need to pay for him to turn a profit. Most opted for the “break even” price. He appreciates breaking the taboo about sharing numbers, so he posted the results online. Another of his blog posts broke down his magazine earnings and profits even to pennies. Efforts like these help demystify why today’s titles are so expensive to those accustomed to subsidized price points.

Major companies are again creating print products, too. Leslie, the magCulture expert, divided the trend into two types of companies: those who want to give their online readers a more tangible form of their abundant, respected content, and those who seek a promotional tool to build out a human and trustworthy side of their all-digital brand.

Major companies are again creating print products, too. Leslie, the magCulture expert, divided the trend into two types of companies: those who want to give their online readers a more tangible form of their abundant, respected content, and those who seek a promotional tool to build out a human and trustworthy side of their all-digital brand.

Falling into the first category is Pitchfork, the website known for constant music news updates and advance album reviews. Its launch of The Pitchfork Review in December 2013 was somewhat ironic, as the site is largely credited with harming the traditional music print press. But its quarterly print magazine is a space for long-form writing for its super-fans—those who prefer, for example, 12-page interviews with Björk to short reviews of her latest albums.

With music journalist Jessica Hopper at its helm, the publication has developed a digital side apart from the main website. Like many of its contributors, Hopper has a significant Twitter presence, which she uses often to tease print content. When she tweeted that Issue No. 5 would feature a 23,000-word oral history of the influential punk band Jawbreaker’s album “24 Hour Revenge Therapy,” she got over 50 responses, one of which was: “Only 23,000? Why y’all slacking?”

Perhaps the most devoted of Hopper’s 20,000-plus followers stem from her contributions to Rookie, an online magazine started by teen icon Tavi Gevinson with an almost cult-like following. In 2012, Rookie also expanded into print with annual, 350-page “yearbooks” of the site’s best features from the last “school year,” or between September and May. “It is not, however, a lame website-to-paper copy-and-paste situation,” Gevinson said in an editor’s letter, ensuring that she would “take advantage of the print situation” and add exclusive content.

So Pitchfork, like Rookie, is producing a magazine because “it sees a value and a purpose in having something that’s branded, that readers can have that’s tangible, and offers something in addition to the web content,” Leslie said. Even with millions of online readers, it’s a “kind of natural extension of being a content provider online and moving into print.”

Then there are the large digital companies that have reached for print in the last few years, looking for a way to build out their brands, expand their communities, and do outreach on another platform. “[They] want a way to communicate directly with the people that engage with their brands,” Leslie said. And the digital world, now like air and water, is not so exciting anymore, he added.

As a website that connects travelers with locals who rent out places to stay through online listings, Airbnb is “a purely digital experience,” Leslie said. So it launched a magazine last November to “flesh out the brand and make it seem a little bit more human.”

Pineapple’s brand affiliation is deceptive: Airbnb’s name and logo are conspicuously absent from the cover. With 128 pages and sleekly designed features on bikes and even the renowned curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, it’s clearly aiming to resemble the Kinfolk-style successes. The indie disguise is working: it already sold out at ArtBook, the MoMA PS1 magazine store. It retails for $12, but it was free for Airbnb’s 18,000 hosts around the world, in an effort to build more trust in the brand and create a community.

Also looking to unite its isolated employees, app of the moment Uber rolled out Momentum for its 150,000 drivers this March. Headlines jeered that the company was “retro” and, with a hint of sarcasm, “eager to get into the lucrative business of print.” With features on cities like Austin and tips on how to stay healthy when you’re always at the wheel, it is hardly promotional. And at a mere 16 pages, it will not be mistaken for a glossy just yet.

But it does join the ranks of other brand publications that are almost extreme extensions of native advertising. High fashion e-retailer Net-a-Porter started Porter last February, and CNET went to print after 20 years of online last November. This year began with the launches of lifestyle website Refinery29’s Refinery29 Editions, Barney’s New York’s The Window, and Timberland’s Document, and United Airlines’ Rhapsody, a first-class-only literary journal. You could even say Uber was late to the game.

Titles like Momentum may not have exciting editorial content, but they are signals that what is happening in magazines is sizeable enough to garner corporate attention and even dollars. They also reflect how digital is like “air and water, just part of what we all do,” making other platforms more exciting, Leslie said.

Titles like Momentum may not have exciting editorial content, but they are signals that what is happening in magazines is sizeable enough to garner corporate attention and even dollars. They also reflect how digital is like “air and water, just part of what we all do,” making other platforms more exciting, Leslie said.

No golden age lasts forever. But this is “the most exciting time because nobody quite knows what’s going to happen,” Leslie said. Digital developments pose continuous challenges to anybody involved in content, making it “impossible to look to the future and predict.”

What distinguishes these young titles as much as their innovations is the youth of their creators. If anyone can figure out how to justify shelling out $20 for paper when one can find an endless amount of free content online, it will be those who have been rowing down the editorial river for most of their lives. But to survive, they will need to cement their concepts, audiences, distribution methods, and business models.

“But do they even have to? What is the lifetime of a magazine?” asked Hershkovits at the Paper offices. Whether these titles make it five years or 30, “what really matters is making an impact and having a voice, doing something memorable, moving people intellectually and emotionally in some way.”

NOBODY CARES ABOUT YOUR OH-SO-COOL KICKSTARTED TACTILE MINIMALIST UNORIGINAL MAGAZINE.

That was the bold, all-caps message emblazoned across the 12th and latest issue of the print magazine Gym Class, which prompted a flurry of responses before it even found its way into readers’ hands. As it turns out, people do care—Gym Class itself is one of the very titles the cover line was poking fun at, and before its editors could reveal more than the cover, the limited edition issue sold out. The message resonated throughout the world of independent publishing, where, believe it or not, most everyone believes that print magazines are deep into their “golden age.”

Forget the Recession-era doomsayers. The score of editors and industry experts I interviewed about the ways they are filling the chasm left by yesterday’s print brontosauruses are resolutely positive about the future of print on paper. They are passionate in their determination to create something in their own right—and they are not in short supply. So many new titles have emerged in the past few years that competition among them is becoming a problem. In apartments and communal studio spaces that stretch from Brooklyn to London, their efforts to turn a new page for print are promising and innovative, but still in search of stability.

“We’ve gone through this process where magazines have really had to fight,” said Rob Alderson, editor-in-chief of the design-centric Printed Pages. He was talking about the beating print took when the Internet started pounding news magazines around 2005, and only got more lethal with the economic crisis that began in 2007. In this “golden age,” Alderson said, there has been “a lot of attention lavished onto independent titles.” Unlike earlier efforts, these “post-Internet print products” are not “trying to compete, stupidly, with the Internet.”

One of the first to see gold in the new start-ups was Jeremy Leslie, who has followed the industry closely for more than 25 years. He considers the new boom “self-evident” from the kinds of innovation he covers almost daily on his popular industry blog, magCulture. “From a creative point of view, I think there’s better stuff around than there ever has been,” Leslie said over Skype from his office in London, stockpiled with publications. “There’s no loss of appetite to make your own magazine. We get sent them here, and they just arrive and arrive and arrive.”

Yet he is cognizant that many people, even some within the industry, still need to be convinced that print is not on its deathbed. It is a point he has been arguing since 2003, when the precursor of his website, his book magCulture, came out. “The tide is just beginning to turn,” he said. “It’s a much sexier headline to hear something is being killed off by something, it’s a much better story. But nothing’s ever as simple as that.”

Nor is it a new story. Magazines were the most accessible form of home entertainment at the dawn of the 20th century. And despite predictions to the contrary with the ascent of radio in the 1920s and then television in the 1950s, popular general interest titles of the times survived and even thrived. Cosmopolitan, for example, then a general interest monthly, circulated to more than a million subscribers each month. Magazines even experienced another heyday in the television-rich 1960s when LIFE, which had been featuring its striking photography since 1936, was selling up to 13.5 million copies a week.

The “print is dead” cries sounded again in the 21st century as digital began its aggressive takeover, and the economy upended. That combination certainly hit the industry hard. Media conglomerates and corporations cut out hundreds of titles, downsizing and sticking with what was safe. Publishers shuttered so many magazines between 2008 and 2009 that Gawker catalogued each new announcement with the tag “Great Magazine Die-Off” and held polls asking which Condé Nast glossy should survive. By no means was this an exaggeration given that the media company eliminated four titles in a single day later in 2009, including the beloved Gourmet, a foodie bible since 1941.

True, a whole swath of print was dying—especially newspapers, news magazines built around summary and analysis of the week’s breaking stories, and major mags that relied heavily on advertisers. Yet while more and more mainstream titles fell into that already bloodied arena, they made room for the indies to take off. The new crop, however, has no designs on becoming a Condé Nast. Many do not even plan to be lucrative. These are passion projects, the work of designers, writers, and journalists who are using their devotion to this tactile platform to create communities or be the go-to voice for niche topics. Instead of advertisers, they rely on sponsors, crowdfunding, and side brands to simply break even.

Ironically enough, print’s oft-cited nemeses—technology and the Internet—turn out to be “a key engine to the success of most the independent magazines,” Leslie explained. For some, like the popular Australian title Offscreen, it is even at the center of their subject matter. The new breed sources material from the Internet, collaborates via email and social media, and finds the design and printing resources they need online to make their ideas tangible. A novice can readily watch design tutorials on YouTube, make layouts on Adobe Creative Suite, and get funding on Kickstarter. The contrast in accessibility is stark from even just 10 years ago, when just to locate an image would mean a long slog through phone calls, mail orders, transparencies, and scanners. Not to mention the huge expense.

“It’s not a Luddite movement,” Max Schumann assured me. He is the acting director of Printed Matter, a store in Chelsea that offers a selection of more than 15,000 periodicals. “The new generation of publishers is very much exploiting and using the things that technology has to offer.”

The Internet has also fostered a virtual community for these indie publishers. Facebook groups serve as forums for editors to combine resources and overcome common hurdles, such as finding the best distributors. Just a few months ago, the British design agency Human After All created The Publishing Playbook, a free, shared folder of resources on Google Drive that instructs its users in how to make a magazine. It offers business models, yearly publishing schedules, subscriber matrixes, not to mention the titular Playbook itself—a 49-page guide that breaks down everything from finding a concept to committing to the long haul.

Andrew Losowsky is a magazine expert, magCulture contributor, and project lead of The Coral Project. Those who choose to create and invest in print today, he said, have to be committed and “have a sense of ‘why am I doing this in print, rather than anything else.’” Printing technology may have become cheaper, but that does not mean it is cheap. Shipping and paper costs can only get so low, and there is no denying the price difference between a blog or an active Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter or Instagram account and, say, a 150-page hardback of thick paper stock like the Parisian biannual Self Service. “And so when it becomes a conscious choice and not a default,” he added, “that forces the quality of print to get better.”

That is not to say the new social media platforms have no part. Social media blasts, dedicated websites and e-mailed newsletters have eased at least some of the difficulties that have always come with trying to promote a print magazine and sell it widely. “The reach is much more, the ability to get money from small groups is much easier, to collaborate, to hear different voices, to reach out,” Losowsky said. “All these things make it an incredibly exciting time.”

![]() So when did this boom start? Although it’s been most apparent in the last five years, and Alderson dates it back two or three years, Leslie saw signs as early as a decade ago. Actually, Leslie said, interest in self-styled magazines really took off 15 years ago, but the economic recession caused a significant disruption. Several titles that served as examples for today’s crop, like Apartamento, a biannual on living spaces and interiors, launched around 2009. Yes, the same years as the mainstream “die-offs.” It is no coincidence that many editors cite these magazines as their initial sources of inspirations. They had the sophisticated, well-defined concepts required to weather the recession.

So when did this boom start? Although it’s been most apparent in the last five years, and Alderson dates it back two or three years, Leslie saw signs as early as a decade ago. Actually, Leslie said, interest in self-styled magazines really took off 15 years ago, but the economic recession caused a significant disruption. Several titles that served as examples for today’s crop, like Apartamento, a biannual on living spaces and interiors, launched around 2009. Yes, the same years as the mainstream “die-offs.” It is no coincidence that many editors cite these magazines as their initial sources of inspirations. They had the sophisticated, well-defined concepts required to weather the recession.

At the same time, especially in Europe, sleek reimagined magazine stores popped up. The art world took note in particular with the 2008 opening in Berlin of Do You Read Me?! The store combined the stock of New York’s storied newsstands with refined, European design. The trend was visible enough by 2012 for Klaus Biesenbach, cultural tastemaker and chief curator of the Museum of Modern Art, to encourage his staff to do something similar. The museum opened up ArtBook @ MoMA PS1 that same year with 200 independent and mainstream titles and New York Magazine quickly named it the city’s best magazine store. It is independent of the Long Island City museum but located inside its modernistic concrete entrance. ArtBook’s manager, Julie Ok, expects to stock 500 titles this year.

Carting a dolly stacked with her favorite magazines to share, Ok led me past the rows and tables of publications that greet visitors on their way to purchase entry tickets and into the museum’s courtyard. Every fall, this outdoor space hosts Printed Matter’s New York Art Book Fair, an ever-expanding zine and magazine festival that has been called the publishing world’s Coachella. Its most recent events in New York and LA each drew more than 30,000 guests.

Ok is not blindly optimistic about the the future of the print medium. She recognizes that newspapers and mainstream magazines “are shutting down all the time. But I think that’s part of why there is this resurgence of independent publishing,” she said. “People are finding that the magazines that they want to read don’t exist, and what better reason to start a magazine yourself than to make the magazine that you want to read?

“That’s what I see when artists and creative people in New York come together and bring me their first issue of their magazine. It’s because they’re either part of a community or seeking a community and they want to put out this thing that has their voice.” Indeed, editors regularly visit the store on foot, laden with dozens of copies of their own first issues. Ok will carry at least a few on consignment, seeing the store as “a jumping off point for a lot of local magazines.”

After the success of ArtBook’s launch, the shop added a hundred new titles the next year and a hundred more the year after that. Now the rotating inventory hovers around 400. The selection varies from niche titles for magazine enthusiasts, established independents like Cabinet and Aperture, to a few staples like Time and Harper’s for tourists who stop off at PS1 on their way to New York’s airports. The independents are her best sellers, she said, and account for about half the stock.

Ok purchases wholesale from independent publishers, paying them 50 percent of each title’s retail price. About half of them come from distributors who act as middlemen between publishers and retailers. The store has built relationships with those such as Idea Books and Motto Distribution, and Ok hopes to work with others that exclusively carry independent publishers, such as Antenne Books in the UK. Distributors make it easier for Ok to nab 20 or so titles at once and that consolidation eliminates the need to make individual contact with about half the magazines ArtBook stocks. It also helps keep track of titles that publish on such varying, often unreliable schedules. The other half of the inventory comes from titles that can’t afford distributors. Ok communicates directly with the staffs of those publications.

For the “passion projects,” Ok’s consignment system works for both the store and the small magazine owners. The publishers get prestige visibility for their magazines and Ok pays them only if they sell. Printed Matter, the Chelsea store with 15,000 publications, has a similar system for the zines that comprise most of its inventory, although it reduced the number of submissions it accepts by two-thirds after its open policy caused a deluge. Ok carries almost strictly magazines, which she defines as serial periodicals, rather than one-off artist books or pamphlets.

The number of copies Ok stocks depends on the magazine’s frequency of publication and its price, but she generally aims for four to six. That range that may sound low, but the store has space constraints and carries back issues, too. Some copies she can predict will sell well. For example, she ordered a larger quantity of the popular British magazine The Gentlewoman’s Björk spring/summer cover, as it coincided with the singer’s MoMA retrospective. The magazine’s Beyoncé cover sold 30 copies in the weekend of the New York Art Book Fair alone. She also always orders a carton, or about 35 issues, of contemporary artist Maurizio Cattelan’s Toilet Paper, the back issues of which can fetch up to 10 times the cover price. Toilet Paper is also distributed by ArtBook’s sister company, Distributed Art Publishers.

The store’s overall best sellers are mostly what the magazine guru Jeremy Leslie calls a new hybrid, “neither independent or mainstream.” These titles are still technically independent and maintain their editorial creativity, but they have become so successful in the public sphere that Whole Foods will stock them. They have even found a home in the “Collectible Magazines” section of Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop.

At their forefront are Kinfolk and Cereal, two titles with pared down editorial design that play up white space and a spare aesthetic, attracting the wealthier demographic that is interested in “slow living.” Their typological aesthetic has spawned a rash of “rampant conformism” from other new magazines. There is even a blog called The Kinspiracy that collects Instagrams of the magazine on thousands of coffee tables, posed next to lattes and halved citrus fruits. Ok said a store patron recently inspected a handful of Kinfolk-type publications and, sensing something deeper afoot, asked, “What are these?”

A sample grouping of Kinfolks from the blog The Kinspiracy.

Apartamento has been another independent mainstay in this vein since 2008, as has Fantastic Man, a men’s semi-annual publication since 2005 with a definitive cover aesthetic. It’s also connected to The Gentlewoman, a biannual launched in 2010 and a fellow bestseller. Along with these trendsetters are newer titles like Hello Mr., a small-scale biannual since 2013 that bills itself as a community for gay men. Ok said a customer recently came in expressly to buy it, saying the mag changed his life. Still others ride the wagon of the slow food movement. Among them are Lucky Peach, Momofuku chef David Chang’s quarterly since 2011; The Gourmand, a three-year-old British food and culture biannual, and Gather Journal, an American recipe-driven biannual, which also publishing in 2012.

While ArtBook is financially independent of MoMA, the museum’s foot traffic is key to its success. Yet Ok said more and more customers come to Long Island City just for the magazine store, something Ok knows from talking with patrons and from watching them as they come in straight from the street, make their purchases, and head back out the doors. The operation remains almost entirely brick and mortar with limited online sales from the store’s website.

To find new titles and stay on top of developments in the field, Ok relies on an arsenal of online resources. There is the weekly print-centric podcast by British magazine empire Monocle, a global affairs title started in 2007 that now even has international cafés; blogs like Leslie’s magCulture, and Instagram accounts for sites that are almost effective enough to act as design databases: Cover Junkie and Steve Watson’s Stack.

Stack was designed for people without access to stores like Artbook. Through its subscription service, it gives readers the chance to browse by sending out a new, surprise title each month. Subscribers pay a flat rate of about £60 a year, or £5 pounds for each mag. Since Stack started in December of 2008, Watson has not had to repeat a single title, nor does it appear he will have to any time soon.

“I’m literally drowning in magazines here,” he said over Skype from his flat in West London, Stack’s home base for the time being. He is planning to hire help for the first time next year. It may be Stack’s growing reputation that has brought so many new magazines via inbox or Royal Mail, “but it definitely feels like there are more things coming out,” he said. That is as good a thing as it is a worrisome one, he said. “It increases competition between these magazines.”

Like so many of the titles Stack distributes, his operation started as a dream that found footing through weekends and weeknights of after-hours dedication. As the magazine world moved faster and the project ate up more and more of Watson’s work week, it came time to sort out finances and logistics. He upped his prices and efficiencies so that in 2014 he could quit his day job as editorial director of Human After All, the creative agency that just put out The Publishing Playbook.

What started as a hobby almost seven years ago is now his full-time gig. He blogs weekly interviews, runs a video review series, organizes regular panels in London and across the globe, teaches publishing courses through The Guardian, posts weekly Instagram covers, and of course, assesses the dozens of publications he receives each month, selecting the worthiest to send out to his 3,100 subscribers.

When asked about the discourse on print going wayward, he shook his head no. After a gulp of Cup o’ Noodles—he was too busy to squeeze in a real lunch—he said, “Actually, I don’t think that many people are saying that anymore.” At least, there are fewer than there used to be. Still, “there’s no denying the fact that print as an industry is in decline—of course it is,” he conceded. But “when you look at the small independents, that’s where you see some really exciting creativity.”

Watson’s aim with Stack is to make these magazines easier to discover and cheaper to buy. The low monthly subscriber fee means that many publications get to readers for up 60 percent off the cover price. Although Watson often receives requests from subscribers for magazines that focus on specific topics, he said he prefers not to know his readers’ preferences. He chooses publications based on the quality of the design and the editorial content so that even a niche topic way outside a subscriber’s usual interests will be enjoyable.

Titles have included the crowd favorites already mentioned—Cereal, Offscreen, and Printed Pages—but also publications with less established followings. For example, Victory Journal is a sports magazine with enormous pages that showcase remarkable photography. Boat is a travel biannual whose editors move briefly to the location they cover in each issue.

Stack kicked off with Watson asking editors: What are the problems that you have as an independent publisher, and how could a different method of distribution help? Perhaps that is why Stack has been so successful for Watson. His mailing list keeps growing, with 500 new subscribers this year alone. It was built from the ground up around the problems print producers face, and came from years of experience writing for magazines that were “used to never having any budget.”