Grave Dilemmas

A real estate shortage for New York City's dead calls for the evolution of its cemeteries.

by Claire Voon

Some call it “Death Alley” for driving conditions so precarious it earned a spot on New York State’s most dangerous roads in 2007. But the narrow and meandering lanes of Jackie Robinson Parkway, which links Brooklyn and Queens, also form another kind of Death Alley. Not only does the roadway cut a nearly five-mile swath through parkland and a sprawling golf course, but it also winds through New York City’s ever more crowded Cemetery Belt. Jagged stretches of ashen headstones from over a dozen graveyards flank the route, some facing the vehicles whizzing by. Others turn to their sides as though determined to ignore the blaring sounds and reckless pace of 21st-century New York.

“GRAVES, CRYPTS & NICHES AVAILABLE,” announces a large sign affixed to a fence that separates tombstones from traffic. The notice belongs to one of the largest cemeteries in the area, Cypress Hills, a nonsectarian necropolis that has straddled the border of the two boroughs for 167 years. But Anthony Desmond, its vice president of operations for nearly three years, estimates its 225 acres will run out of available plots in 75 to 100 years. In the business of life to death, that is shorter than it sounds.

The subway trundles over Washington Cemetery, one of New York City’s first public cemeteries to run out of space. Landlocked, the city’s burial grounds are unable to expand to accommodate its future dead.

Other cemeteries around the city give themselves even less time. Four-and-a-half miles away, in the Queens neighborhood of Kew Gardens, Maple Grove anticipates only another 30 to 40 years until it has no in-ground burial space to sell. The nonsectarian cemetery currently has over 83,000 interments across its 65 acres. At Flushing Cemetery, the timeline is shorter still. If the 75-acre establishment continues selling its graves at its current yearly average rate, its inventory of plots will be gone in six-and-a-half to seven years.

“It’s something I probably worry about almost every day, at this point,” Flushing’s general manager John Helly said with a hint of weariness. “Every decision that I make, I’ve got to make sure that I’m making the best use of every piece of land that I’m taking.”

By 2040, 15.6 percent of New Yorkers will be aged 65 or older. This leap from 12.2 percent in 2010 signals a spike in the death rate. Today, of the approximately 51,000 people who die annually in New York City, nearly two-thirds choose earthen burials. But as land supplies steadily deplete, many cemeteries within the five boroughs increasingly struggle to provide space for this traditional form of memorialization, rooted in the religious practices of New York’s early Dutch settlers.

“Cemeteries: The End is Near,” Gotham Gazette warned in 2005, noting that Green-Wood’s 478-acre grounds in Brooklyn, now home to 560,000 permanent residents, was then just five years shy of capacity. And yet, five years later, under the headline, “City Cemeteries Face Gridlock,” the New York Times extended Green-Wood’s sales life by another half-decade. Today, Green-Wood’s president of 29 years, Richard Moylan, believes the cemetery has enough space to last through 2020.

As Desmond remarked, “It’s no secret. It’s out there. There are many cemeteries that are dwindling, that don’t have much space left. What needs to be done is, you have to be creative, and you have to make the right decisions to maximize your inventory.”

“It’s no secret. It’s out there. There are many cemeteries that are dwindling, that don’t have much space left.” — Anthony Desmond, vice president of operations at Cypress Hills

Throughout the city, cemetery boards have been rethinking their operations, devising innovative solutions to maximize the full potential of the land they have left to sell. With grave sales as a cemetery’s primary source of income and available plots so few, strategies that keep revenue flowing are critical for survival. Cemeteries must consider the cost of maintenance for both their dead and those yet to die, whether or not sales continue.

In the past, insolvent boards have relinquished their duties, leaving grounds to fall into ruin. With the city’s land at a premium, some developers have bought graveyards, replacing them with more remunerative structures for the living. Fortunately, new consumer trends have emerged in the death industry that demand less real estate, most notably the rise of cremation over the past half-century.

This willingness to modify the customs of memorialization to match new public preferences has proven key to the cemetery business. In the May 2013 issue of American Cemetery, David Ward, the president of a cemetery landscaping firm, noted that there have been more changes in cemetery planning in the past 25 years than there were in the whole of the previous century.

Yet, as tensions between the metropolis and its necropolises mount, critics of the modern burial industry argue that to serve the city’s dead for generations to come will take more than new models of permanent memorialization. The real solution, they contend, requires the harnessing of new technologies and innovative architectural designs. Burial practices must be completely re-envisioned.

David Ison, the Director of Sales and Marketing at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, emphasized that his team must “strategically plan,” which means staying aware of clients’ current needs while remaining open to the possibility of major modifications. “Because one thing I can assure,” he said, “is that two generations, three generations down the road, it’s going to look like something we can’t even imagine.”

“One thing I can assure is that two generations, three generations down the road, [the cemetery is] going to look like something we can’t even imagine.” — David Ison, director of sales and marketing at Woodlawn

Across the world, cemeteries in other densely populated cities have already undergone facelifts, especially those that search skywards for space. In Santos, Brazil, the world’s tallest cemetery stretches 32 stories high with coffins fitted into wall recesses known as crypts.

The challenge of graveyard overcrowding and redesign is not unique to New York, and neither is it new. But past solutions, like transferring bodies to new locations, have proved contentious and are unlikely ones for the current era. One need only glance at the sites of New York’s cemeteries to realize that efforts to find land for the dead today in the world’s sixth most populous city have reached an impasse.

Many cemeteries sit beside subway tracks or busy streets, their serene settings in conflict with the urban environment. Around the Jackie Robinson Parkway, eternal rest comes with the rumble of passing traffic. The roadway actually curves as it does because the city aimed to build around the existing cemeteries; yet, in 1930, it still disinterred some 400 bodies to use that property. In Upper Manhattan, avenues and streets border Trinity Cemetery, established in 1842 as an extension of Trinity Parish’s downtown churchyard. Thirty years later, when Broadway extended north, it bisected the cemetery, creating a valley of traffic between the resting grounds of more than 20,000 souls.

Surrounded by the living on all sides, Trinity has no way to expand on site—a familiar limitation in cemetery circles. The city’s urbanization over the past 150-plus years has left its graveyards landlocked. There are no current plans for a new necropolis, and founding one would be nearly impossible. Not one large, open tract is available. A corporation would also face legal hurdles if it wanted to purchase any property for burials, including obtaining permission from the district Supreme Court. In a city of such frantic residential and commercial development, anyone choosing to market to the dead would make poor competition.

“If I were a physician, and one of those busy men of Wall Street, who complain of the wear and tear of an unresting brain which brings sleeplessness and prostration in its train, came to me for advice, I should prescribe a daily half-hour walk in the churchyard of old Trinity.” So wrote one New Yorker, John Flavel Mines, in his 1896 recollections of walking through Trinity’s burial grounds. That “garden of the dead,” he continued, “breathes peace and healing into the tired and overworked brain.”

Years ago, particularly before the emergence of public parks, those who sought escape from urban life found relief, like John Mines, in Manhattan churchyards and the private cemeteries that the early Dutch settlers established in Queens. Once there were countless burial grounds across New York, but the demands of the city’s burgeoning population eradicated most. Two centuries ago, Manhattan alone was home to dozens of active graveyards. At least 22 lay south of City Hall, as the historian Debby Applegate noted in the collection of essays Green-Wood at 175. Today, only three active Manhattan cemeteries remain: Trinity and the two Marble Cemeteries in the East Village. All are landmarked as historical sites.

The New York Marble Cemetery occupies a lot bounded by East 2nd and 3rd Streets, Second Avenue, and Bowery. Nearby, another Marble Cemetery lies on East 2nd Street between First and Second Avenues.

Initially, a cemetery’s biggest threat stemmed from health, not land, concerns. In 1806, a report by the New York City Board of Health proposed prohibiting additional grave sites in Manhattan, suggesting that parks replace those “receptacles of putrefying matter and hot beds of miasmata.” It took another 45 years, however, for the city to ban public, in-ground entombments—albeit just south of 86th Street—an interdict that remains in effect today.

By the 1830s, interments on the island had reached an annual rate of 10,000, and the population had nearly tripled over the previous decade. People located to new, emerging neighborhoods as the city stretched north; churches, following their congregations, sold their sacred properties downtown to developers whose priorities decidedly favored the living. In a scathing editorial for the daily New York Aurora published in 1842, Walt Whitman expressed outrage at a developer who dug up bodies from a Baptist cemetery at Delancey and Chrystie streets. The incident was only one of many in the 1830s and 1840s, when the city carved out and widened streets, destroying burial grounds and disinterring their residents.

Today, disinterment remains legal, although New York State’s Division of Cemeteries’ current legislation discourages it. The Division’s laws apply to the region’s public, not-for-profit cemeteries—about 30 within the five boroughs. Those intending to remove a body from a graveyard need written consent from the cemetery; the lot owners; and the decedent’s surviving spouse, children, and parents. Cemeteries will thumb through records, peruse death certificates and wills, post notices and newspaper ads, and send letters to any last known addresses. Once found, if any family member declines the disinterment request, obtaining a court order may overturn the decision.

But in the mid-19th century, ministers could simply sign off on their deeds, said Caroline DuBois, president of the New York Marble Cemetery, which led to frequent mass disinterments of churchyards. Workers loaded carts with unclaimed bodies bound for potter’s fields and reburied thousands of others in new, verdant cemeteries that found property in Queens and Brooklyn, still, then, mostly farmland. Green-Wood, New York’s first of these vast, park-like necropolises and today one of the country’s most renowned, witnessed its first burial in 1840—the remains of four people removed from one of the Marble Cemeteries.

Green-Wood, the first rural cemetery established in New York City, boasts 478 acres of greenery today.

Observing Manhattan’s burial grounds as “teeming with dead bodies” and surrounded by “compact masses of buildings,” Henry Pierrepont and other prominent Brooklynites had purchased almost 200 acres of land in their borough to establish Green-Wood. Their vision of providing New York’s population—then around 312,000—with proper resting places in a natural and quiet setting was inspired by Pierrepont’s trip to America’s first such “rural cemetery,” Boston’s Mount Auburn.

The state, too, addressed severe overcrowding in Manhattan’s churchyards, and passed the Rural Cemetery Act in 1847, which permitted nonprofit corporations to establish commercial burial grounds in rural regions. Shortly after, a number of public cemeteries, including Calvary, Cypress Hills, the Evergreens, and Woodlawn—all still active today—opened their gates. Although city dwellers initially balked at the notion of final rest so far from their churches and ancestors, attitudes quickly changed. In his book, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: New York’s Buried Treasure, Jeffrey Richman, the cemetery’s historian, wrote that Green-Wood received 100,000 interments in its first 25 years, and a greater number of New Yorkers purchased large family plots for future use.

The remains of thousands of people removed from crowded churchyards eventually filled many of these new spaces so Manhattanites no longer lived in close proximity to the dead. Woodlawn’s ninth annual report, written in 1872, places its total interments at the time at 11,536. Reinterments comprised over half that number.

On a cool March morning, as a light drizzle began to fall, John Helly stood near the edge of Flushing Cemetery and gestured toward a flat field. ”This is my last open area,” the 47-year-old manager said. “I have to be able to put in as many burials as I can. After this sells out, I’m technically out of land.”

He seemed to be exaggerating because at a glance, Flushing appears to have plenty of unused space open for multiple memorials in other sections of its property. Cemeteries, however, inevitably have more vacant plots than ones for sale since many people make advance purchases, or “pre-need” arrangements. And sometimes, for whatever reasons, the owners simply never fill them. Many plots accommodate two or three bodies, stacked on top of the other. To reopen these graves, most cemeteries must, therefore, also leave sufficient space between headstones for the digging crews and their machinery.

A cemetery’s landscape may not explicitly reflect its current space conditions, but its layout often does reveal how land pressures heightened as it aged. Maneuvering his car slowly through Flushing’s curving roads, Helly first passed the cemetery’s older sections, dominated by large family plots, where headstones dating to the mid-1800s huddle haphazardly in scattered clusters. As he drove through zones more recently filled, the large, sparsely distributed lots gave way to headstones in neat, compact rows. “The land is very economical,” Helly said. “There’s no waste of land over here. Everything’s tight as it could be.”

At Maple Grove, the grounds convey a similar shift in burial layout. The earliest sections follow the style of a rural cemetery, with upright tombstones engraved with old Dutch family names tucked up on the hills, resting in the shade of large maples and evergreens. Bonnie Dixon, the cemetery’s executive vice president and general manager, explained that changes in burial planning practices have reduced the distance between markers. As the cemetery matured and expanded, it began placing its interred nearly toe-to-toe. “The days of having family plots and planning for generations are moving by the wayside,” Dixon said, “replaced by people buying more for their parents.”

Those aging, large plots, as it happens, have proved a godsend. As cemeteries design tighter layouts, the search for available land has led them to eye the empty spaces. Maple Grove, for example, owns lots with space for as many as 18 family members, but these rarely fill. Those graves would remain empty forever if not for the law that authorizes cemeteries to reclaim them. For slightly over a decade, cemeteries have had the right to sell a grave older than 75 years that was never used or that had a lawfully removed body.

Maple Grove, which runs one of the most active reclamation programs in the city, even hired a part-time employee to research potential graves for recovery. Like a disinterment request, reclamation efforts require cemeteries to locate plot owners and ask if they wish to retain their burial rights. If a thorough search for descendants proves unsuccessful, the cemetery may then petition the state to request reclamation.

Since 2005, Maple Grove has successfully recovered 206 graves, all purchased under a statutory price, set as the original price of the grave with four percent interest on the number of years the grave was owned. Cypress Hills, too, began reclaiming graves early last year that yielded a boost in inventory of some 180 individual spaces. Desmond said his team anticipates finding more.

But not all cemeteries boards support this strategy. “We don’t believe in it,” said Anthony Salamone, who now sells plots at Evergreens. “It’s not going to happen on our watch.”

Instead, Salamone, formerly the cemetery’s assistant superintendent, checks the Evergreens’ records every day for unsold family lots as opposed to reclaiming empty graves in partially used ones. His efforts have freed up an additional 120 individual, sellable spaces.

Green-Wood, to ease its reclamation process, started “Green-ealogy,” a genealogical research program that has successfully connected some descendents to ancestral graves. But its program remains relatively small: subdividing those lots requires careful consideration to avoid affecting the appearance of the cemetery.

“And that’s prime,” Moylan stressed.

Behind Green-Wood’s towering Gothic Revival-style main archway, where a colony of green quaker parrots nests in the brownstone crevices, lie 478 acres of lush parkland. Pathways wrap around gentle hills, where grand mausoleums housing generations of New Yorkers wedge themselves, their columned facades enjoying vistas of copses and smooth ponds against the backdrop of the concrete city. Obelisks with lengthy, hand-chiseled inscriptions tower beside tombstones resting beneath old trees, naked in the winter and flaming in the fall. All around, angels and classical figures, arrested in stone, watch over the dead or pose in prayer.

Throughout Green-Wood’s development, architects meticulously shaped the site into its natural and majestic setting. This exquisite garden quickly became “the most fashionable place to spend eternity,” as Applegate described. For the living, it beckoned for contemplative walks among its graves, scenic rides in horse-drawn buggies, and even picnics on its tranquil grounds. So popular was its greenery in a swelling urban maelstrom that city planners got the message: construction began on Central Park in 1857 and Prospect Park in 1866. By then, Green-Wood’s annual number of visitors had jumped to half a million. It remains a popular tourist destination today, attracting people from across the globe.

So in Green-Wood’s plans for the future, to preserve its bucolic beauty ranks high on its board’s considerations. “I sort of feel our mission is two-fold,” Moylan said. “It’s to protect the beauty of what we have here but also to bury the dead as long as we can.”

“Our mission is two-fold. It’s to protect the beauty of what we have here but also to bury the dead as long as we can.” — Richard Moylan, president of Green-Wood Cemetery

Still, Green-Wood has had to transform some of this prized landscape to create saleable lots. Over the years, it has closed off charming roads and paths. It also filled one of its five ponds to use for a soil processing site before converting it for use as a burial zone. Completed last year, the redesign yielded three community mausoleums and hundreds of in-ground graves. But Moylan said changes this dramatic are unlikely to occur again, even if they do extend Green-Wood’s sales life.

Cemetery managers across New York have been forced to cut into spaces originally unintended for burials. Grappling with similar quandaries at Cypress Hills, Desmond reflected on the “very fine line between beautification of a cemetery and maximizing your inventory, because you could have a tree somewhere or you could have three graves there.” One method of space recovery his team frequently attempts is finding ways to create what he calls “border graves.” At Cypress Hills, many family lots lie as much as nine or 10 feet from the street, so that roadside space may yield individual plots.

Woodlawn is also surveying its land with a creative eye, searching for opportunity in unlikely areas. A number of its private mausoleums rest on circular lots, which at times connect to create empty pieces of property shaped like triangles. Ison believes that one day, those spaces—though insufficient for full-burials—may hold dozens of cremated remains, often called cremains.

Creative as these solutions may be, they are ultimately limited. Only so much property exists for a cemetery to continue offering attractive and respectful earthen burials. More and more, New York’s cemeteries are shifting from that custom, investing instead in above-ground memorialization. The resulting structures are nowhere near as tall as those in other countries, but they are changing the appearances of these historic landscapes in ways never before imagined.

Like stone tents pitched on a scenic campsite, Green-Wood’s many private mausoleums represent one of the largest outdoor gatherings of burial chambers in the world. In them rest some of the most celebrated New Yorkers—including the Steinway piano manufacturers—their names carved into looming, elaborately decorated facades. The thick walls of stone stand in stark contrast to the sleek, glass-fitted building integrated into the slope of a hillside by Green-Wood’s western border, the cemetery’s newest forever home for urbanites.

Standing five stories tall and complete with an indoor waterfall, Green-Wood’s newest mausoleum is a modern luxury home for the dead.

A vision of modern architecture, Hillside IV Mausoleum is more suited to the Williamsburg waterfront than to this pastoral setting. Stacked five stories high in this luxury home for the dead are over 3,000 granite and marble crypts. Indoors, a waterfall cascades from the top, collecting in a glassy pool on the first floor. Armchairs sit on Tibetan wool carpets and Indian slate floors, surrounded by seasonal flowers and plants. Through a skylight, the sun streaks down a center shaft, around which twists a stairway crafted of hardwood and steel. A ride in an elevator also takes visitors outdoors to the hill’s apex, where 19th- and 20th-century headstones wait.

With its modern architecture, Green-Wood’s Tranquility Gardens stand out against the rest of the cemetery’s pastoral setting.

Near Green-Wood’s entrance, another steel-and-glass complex overlooks aging tombstones and mausoleums. The contrast, though striking, is somehow not jarring. Dedicated entirely to cremation memorialization, Tranquility Gardens fits many more remains on its land in a mixture of outdoor repositories and columbariums housing shelves of niches. But with its shallow pond of colorful koi fish and tall bundles of bamboo, it feels far from a home for the dead. As with the Hillside IV Mausoleum, one could mistake the inside of each one-story building, fitted with floor-to-ceiling windows, for the lobby of an upscale hotel; the only giveaway is the walls of glass-fronted niches that hold urns of jade, porcelain, and marble. The number of cremations at Green-Wood, Moylan said, has increased in past years, while full casket burials are gradually declining. It’s a trend he and others in the business fully expect to continue.

This year, the national cremation rate will surpass that of burials for the first time, reaching 48.2 percent, as the National Funeral Directors Association reports. By 2030, it will reach 70.6 percent. Industry experts attribute the burgeoning popularity of cremation to its affordability compared to in-ground burial: in its 2014 study, the Cremation Association of North America found that the national median cost of cremation with limited memorialization services is about one-fourth of that of a funeral with burial. Changing cultural perceptions, too, have fueled the trend. The Catholic Church, for example, lifted its ban on cremation in 1963. The method is also practical in our more transient society, allowing relatives to easily transport ashes to any desired spot for memorialization; on the other hand, transferring a body, especially across state lines or across the sea, requires careful preparation and navigation of local and national legislation. When Anthony Salamone first joined the Evergreens in 1970, the cemetery acquired only one or two cremains a month. Today, it receives two or three a day, sometimes even by mail from relatives who have moved.

When cremation first emerged as an option, David Ward said that many in the death industry viewed it as “a nemesis to cemeteries because it was a cheap alternative.” It was also the choice of the curious and better informed in those days, as funeral directors did not propose this alternative to the families they served. The national cremation rate remained just under five percent in the early 1970s, but as perceptions of the practice changed over the next decade, it quickly reached double digits.

Behind Trinity’s old headstones, modern mausoleums offer hundreds of spaces for above-ground memorialization of cremains.

Today, the attitudes of most industry professionals are poles apart from those of their predecessors. Last October, American Cemetery relaunched as American Cemetery & Cremation, increasing its coverage of the burial alternative. Cemetery directors, especially those facing urban pressures, now value—and depend on—the public’s growing acceptance of the practice.

Ward said many welcome the shift because “it gives you a lot more possibilities to work with than they used to have.” From his landscaping experience, cremains consume as little as a quarter or even a fifth of the land needed for full-body caskets. And that yield increases further once a cemetery begins building above-ground structures.

Woodlawn, which owns about 20 to 30 acres of undeveloped land, is going through what Ison called “a phase of growth.” Its team is currently working closely with architects and developers on designing the open space, and accommodating cremation options is now paramount. While Woodlawn once hosted, on average, a couple of thousand in-ground burials and a thousand cremations each year, those numbers have now flipped. From Ison’s estimates, the cemetery’s open regions could hold thousands of burials for ashes.

At Woodlawn’s office, those making final life plans may flip through a brochure dedicated entirely to the cemetery’s slew of cremation options, which go far beyond those of the typical columbarium. Ison and his team have carefully developed an inventory that both caters to the various needs of clients and blends in with Woodlawn’s natural settings.

“We will never compromise what Woodlawn is,” Ison said firmly. “So everything that we will put into place will have to conform to the Woodlawn expectation. It has to have the look, it has to have the feel of Woodlawn because it’s just too important to lose that.”

Ashes may be placed in cored rocks, commemorated with a plaque, at Woodlawn’s Brookside Cremation Garden. (screenshot via Woodlawn’s cremation brochure)

At the cemetery’s highest perch is Hillcrest Mausoleum, where parkland vistas change with the seasons. Woodlawn recently finished constructing the first phase of the large domed complex, which yielded 1,000 spaces for cremains and another 1,000 for caskets. Nature lovers will find solace at Woodlawn’s Brookside Cremation Garden, where niches overlook a brook that flows into the Bronx River and spaces seamlessly tuck into the walls of bridges. For $10,000, Woodlawn will nestle ashes into specially cored rocks by the water. For those who would like to spend less, $500 buys the right to scatter ashes in a communal ossuary. Subtle bronze plaques rather than conspicuous inscriptions commemorate each individual.

Ison said such individually tailored memorialization options have become more and more popular. These new designs bear little semblance to the centuries-old offerings of uniform, underground graves. But buyers seem to like them, which has encouraged cemeteries to keep investing in these modern alternatives. Spaces at Hillcrest went on sale about a year ago, and they have been selling well. At the Evergreens, two community mausoleums are near completion. But as early as March, Salamone had already accumulated a list of about 30 people who reserved places. Similarly, before Canarsie opened its first outdoor mausoleum, Gate of Heaven, in January, it had a list of 185 interested buyers for its 203 crypts. The cemetery has since laid the foundations for its next phase of mausoleums as part of a master plan to develop four back acres over the next 20 to 25 years.

Transitioning is tougher for some cemeteries, especially those with clientele who either place a higher value on full-body burials or whose traditions simply forbid cremation. With its largely European community, St. Michael’s Cemetery in Queens has built nine mausoleums since 1986—and its niches and crypts are nearly sold out, according to its general manager Dennis Werner. But as immigration changes the identity of the city, some cemeteries increasingly have to consider cultural preferences as they plan their futures, especially those of some Jews and East Asians.

“That’s a very big chunk of New York right there,” said Lewis Polishook, the Director of the New York State Division of Cemeteries.

Although Jewish tradition does not favor above-ground burials, Mount Lebanon Cemetery has offered options in community mausoleums since the 1980s. In part because of that early adoption, the 80-acre cemetery still has plenty of available space. Its first two mausoleums are almost sold out, and the third recently underwent expansion. “We have land to sell for many, many generations to come,” Matt Ivler, Mount Lebanon’s manager, said. “At the rate we’re going, we’ll probably have more land than we’ll ever fill up.”

Flushing, too, now has plans to build its first mausoleum behind its office, even though its largely Asian clientele had not expressed interest in the past in above-ground memorialization. The small community space will house 2,200 cremation niches and 200 crypts. “If it does well, we know it’s time to put our money on bigger buildings,” Helly said. He prefers leaving a large field near the cemetery’s gates open for aesthetic purposes but has to consider that land for future mausoleums.

“If I don’t, I’ll be cutting the life of the cemetery short,” he said. “I have to find ways to extend the life of the cemetery.”

The sea of stones emerges beneath the rumbling F train as it pulls into its Bay Parkway stop. Four streets, including the major thoroughfare that is McDonald Avenue, cut neatly through Washington Cemetery and its 100,000 burial plots packed across 110 acres in the heart of Brooklyn. The borough’s largest Jewish cemetery opened its gates in 1861; today, it effectively has no space left to sell. Within its five sections anchored in the always-evolving quilt of the city, aging tombstones and obelisks dot every portion and corner of the land, clustered to resemble a miniature model of midtown Manhattan when seen from the subway platform. The cemetery has reached capacity long before its peers, largely because it adheres closely to Jewish law and offers limited, in-ground options for cremation.

One cloudy morning in March, four men armed with shovels and machinery stood within that gray maze, looking down a deep hole in the ground. The funeral was scheduled for the following day. Even though Washington does not generate income from new sales, it receives revenue from past reservations that “little by little, are unfortunately getting used,” as its manager Marisa Tarantino said. Cemeteries charge a fee for each grave opening to cover the cost of the digging crew; at Washington, that amount is $1,700. But once each of its graves is occupied, profits will halt, and how Washington plans to sustain itself after remains uncertain. All Tarantino had to say on the matter was: “It’s being maintained as long as funding allows.”

Under law, cemeteries must establish two funds. The permanent maintenance fund, which receives 10 percent of gross proceeds and $35 of every sale, is reserved for tending the cemetery grounds—in theory, in perpetuity. The current maintenance fund, receiving 15 percent of any sale, is used for any necessary expenses. Cemeteries also often set up a perpetual care fund, a generally voluntary endowment that plot owners pay to care for individual graves. All of those funds, in principle, earn annual interest.

New York’s graveyards are exempt from paying property taxes, which relieves budgetary pressures somewhat; still, all managers can only hope that their endowments have grown enough through the years to provide for a future beyond sales. The only cemeteries with fewer financial burdens are those run by religious organizations. Trinity, for example, receives the majority of its funding from its parish. Similarly, Catholic Cemeteries of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn handles the operations of 10 Catholic cemeteries.

Managing death is an expensive business, especially when beautification is a high priority. The Evergreens runs on an annual budget of $5 million, according to Salamone. Green-Wood’s is a whopping $14 million, half of which is spent on labor alone to groom its innumerable hills and steep banks. But neither cemetery is too concerned about its funding, thanks in part to savvy investment of their perpetual care funds, significantly shored up by historical revenues.

Green-Wood has an annual budget of $14 million, half of which is spent on labor alone.

Still, selling graves strategically is key to retaining financial comfort. At Maple Grove, Bonnie Dixon described balancing transactions as “an economic threading of the needle.

“We now don’t necessarily want to sell graves just to sell graves because every time you do, it’s a future obligation to bury in those graves,” Dixon said. “But you want to sell some graves every year so you have some income to pay your people.” By spreading its sales, the cemetery buys itself time to devise new solutions and reclaim unused graves. Operating costs will also decrease overtime as stockpiles shrink and workers are no longer needed for digging. In recent years, new machinery such as tractors and power mowers have also replaced manpower and lowered costs.

New York City’s history is filled with tragic tales of cemeteries, mostly small, private properties, whose owners proved unsuccessful in strengthening or investing their funds and in vigilantly maintaining their grounds. Until two decades ago, wild plants enveloped the New York Marble Cemetery, forgotten over time and run by a lone trustee. A nonsectarian burying ground—Manhattan’s oldest—the Second Street property survived the construction spree of the 19th century because land-hungry individuals needed all independent vault owners to sign off on its sale. None who attempted, including reformer Jacob Riis who envisioned a playground there, succeeded. It remained a cemetery, albeit a hardly respectable one in those days, as its owners largely neglected it. In 1997, a woman named Anne Brown discovered the overgrown lot, its walls vandalized and collapsing, while hunting for information about her ancestors. Outraged, she used an endowment from early fundraising efforts to set the property on a difficult path to recovery.

The New York Marble Cemetery is now a green oasis in the heart of the East Village.

Today, the half-acre lot, bordered by apartments and the Bowery Hotel, has a proper board of trustees that keeps its grounds trimmed and attractive. Descendents of the original 19th-century purchasers are among the very few who may still be interred below 86th Street as long as they provide an affidavit proving their burial rights. As DuBois—herself a descendant—noted, the cemetery still has space in each of its 156 subterranean vaults “for countless generations to come.”

The Marble Cemetery’s recovery is a triumph, but occupants of other grounds lie beneath garbage and toppled headstones. By the 1980s, there were so many abandoned cemeteries across New York that Pearse O’Callaghan, the then-Director of the Division of Cemeteries founded an organization to restore them. Now known as Friends of Abandoned Cemeteries of Staten Island—only because the bulk of its work has occurred in that borough—the group currently manages 11 burial grounds, raising money and gathering volunteers for cleanups.

Many tombstones in abandoned cemeteries, such as this one on Staten Island, have collapsed over time.

“How cemeteries get abandoned is they get full,” Lynn Rogers, the organization’s current executive director, explained. “So they can’t sell new graves, so they can’t make any money, so they can’t hire the landscaper, [pay for] the upkeep, and eventually they can’t function.”

“How cemeteries get abandoned is they get full. So they can’t sell new graves, so they can’t make any money . . . and eventually they can’t function.” — Lynn Rogers, executive director of Friends of Abandoned Cemeteries of Staten Island

Defenseless, some do not survive, such as the homestead burial ground that once occupied property where Staten Island Mall now stands. When its presence was made known to the mall’s developer after he purchased the land in the 1980s, a judge advised him to leave it untouched. “He did it anyway, plowing it over and removing everything to the dump,” Rogers said.

There is no legal process for handling these abandoned urban cemeteries, according to Polishook. In towns, state law dictates that the town must take charge of the land and perform minimal but regular maintenance. In the city, at times, the Parks Department obtains inactive, private burial sites through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure; other transfers of ownership occur through the Department of Citywide Administrative Services. But the city, as Rogers said, “always took the position that they’re not in the cemetery business.”

Volunteers upright a tombstone at the Staten Island Cemetery, abandoned in 1954.

In early April, she and about 40 volunteers from Richmond County Kiwanis Club cleaned up the Staten Island and Fountain Cemeteries, two adjacent burial grounds abandoned in 1954. While under government management, the sites had collected debris, headstones vanished under savage thickets, and drug addicts paid their dubious respects.

Well aware of the tremendous effort needed to oversee abandoned cemeteries, the city prefers to find alternate and capable corporations to shoulder the duty, but the search is challenging. “In practice, what we’ve tried to do is get another cemetery to come in and either run it as a manager or merge with it and take it over,” Polishook said.

From the parking lot on top of a hill, visitors may see almost all 13, well-kept acres of Canarsie Cemetery, situated near the L train’s last stop in Brooklyn. Now owned by Cypress Hills, Canarsie looks completely different than it did just five years ago, when it was managed by the city. When the Cypress Hills team arrived, various sections of Canarsie were covered in wilderness, and sidewalks begged for repair. The cemetery had spent years passing through various city departments, burdening budgets. Plans to find it a new owner began in 1975, but 35 years of complications passed before Cypress Hills sealed the deal at last.

Even though Canarsie’s landscape initially needed severe restoration, it provided Cypress Hills with an invaluable endowment: more acreage for burial. On top of the four acres reserved for later development, another overgrown area yielded 700 graves once cleared. With a $5,000 price tag, each one brings more security for the future.

That market-driven cost of graves is one thing cemetery boards cannot change about their businesses. Like that of any other parcel of New York City’s real estate, it escalates every year. Securing a plot in Manhattan is now a privilege: few may afford the $20,000 former mayor Ed Koch paid in 2008 for his spot at Trinity Cemetery. The 22-acre grounds currently has burial space “available under extraordinary, case-by-case circumstances,” according to its director Daniel Levatino. Although its mausoleums remain active, a crypt costs about $12,000 and a niche, $2,500.

“Everything is so expensive,” said Josephine Dimiceli, who runs midtown funeral home Dimiceli & Sons. “Most people are looking for the most economical way out.”

Cemeteries set their own prices, and no limits exist. Some of the most expensive graves are at Green-Wood; buying burial rights on its terrain is tantamount in the cemetery business to purchasing a luxury apartment in SoHo. There, a single grave, which may fit up to three burials, begins at $15,000, not including fees. A single grave for two at Flushing and Cypress Hills begins at $7,425 and $7,500, respectively. At Calvary Cemetery in Queens and Canarsie in Brooklyn, the lowest price for a two-person grave is about $4,600. And on top of that charge, people have to pay the grave-opening fee. “Which for some people,” Dimiceli said, “means they can’t afford to be buried in their ancestral plot.”

The prices of crypts and niches, such as these at Cypress Hills, depend on how high the space is within a section.

In general, the cost of a crypt is similar to that of a grave, although there are now more available and their price range is broader. Like on shelves in a supermarket, placement in a community mausoleum determines cost: crypts at eye-level are the most expensive, while the highest are more affordable. At Cypress Hills and Canarsie, they go for around $6,000. But in Green-Wood, they are actually even more expensive, with single crypts starting at $20,000. The most expensive crypt at the Evergreens is $23,000.

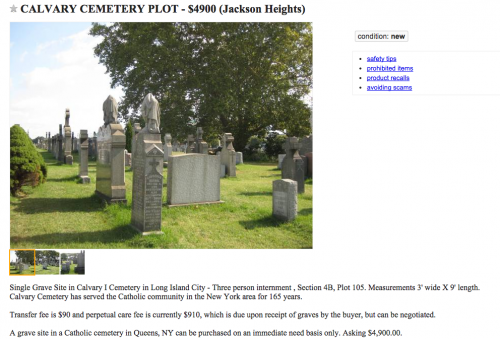

The price of graves is so high that some owners have turned to selling their pre-purchased spaces—often online, since a cemetery’s buyback offer, set by the statutory fee, is usually very low. Websites, from Final Arrangements Network to Grave Solutions, have emerged to facilitate these transactions. People are even selling their graves on Craigslist, like Judy Kaszas, a 86-year-old Queens native who has listed her completely unused plot for nearly a year. Her three-person space, purchased for $250 in the 1980s, rests in a desirable section of Calvary, a 167-year-old Catholic cemetery in Queens that is also reaching capacity. But realizing the cost of today’s graves, she has listed it at $4,900—in part, to fund the niche and urn she has decided will cradle her ashes.

Cremation is one way people cut costs, but for those who don’t want to—or can’t—be cremated, the only option may be to leave the city. Upstate, space is plentiful, and prices are cheaper. An at-need grave with an upright headstone at Rosedale Cemetery in New Jersey, for example, starts at just $1,900.

At Greensprings Cemetery, in Newfield, New York, an individual grave costs only $1,000. But Greensprings was established in 2006 in response to another desire strengthening among those considering their burial options. Boasting 125 acres of sprawling meadow with not a headstone in sight, the cemetery offers only “green burials”—completely natural ones that use fully biodegradable receptacles. Nothing enters the ground that cannot disintegrate and be absorbed. Only the flat markers lodged in the grass, inscribed with names, indicate that this park is a cemetery.

While people grow more cost-conscious, they are also becoming more aware of caring for the environment. “I’ve actually talked to people who have expressed concern about New York City cemeteries,” Greensprings’ director Joel Rabinowitz said. Many urbanites, he explained, choose to rest there because they would rather return to nature than lie in stone-filled, polluted grounds.

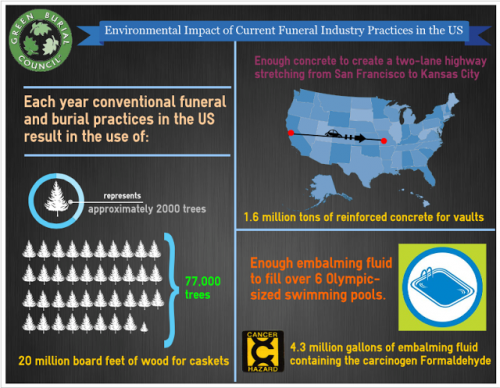

As a whole, the burial industry is extremely wasteful and funnels chemicals and inorganic resources directly into the earth. According to Mary Woodsen, who works with the Green Burial Council, caskets now consume tens of thousands of tons in steel each year, and vaults, 1.6 million tons of concrete—enough to create a two-lane highway from San Francisco to Kansas City. The country also uses enough embalming fluid annually to fill over six Olympic-sized swimming pools; all this fluid eventually dissipates into the ground. The mixture also contains formaldehyde, a carcinogen that is hazardous, particularly to embalmers. No law requires embalming, but it remains a common request among families.

“This is all extra stuff that we’re sticking into the ground . . . and for what purpose?” Rabinowitz asked. “The way that bodies are typically buried in this country leaves a lot to be desired from an environmental, ecological point of view.”

“The way that bodies are typically buried in this country leaves a lot to be desired from an environmental, ecological point of view.” — Joel Rabinowitz, director of Greensprings Cemetery

But Newfield is still 230 miles from New York City and requires a journey some may find tiresome. Those conscious of their ecological footprints also have to consider the environmental costs of transportation on top of the energy consumed to refrigerate a body for its trip.

New Yorkers may one day see the Manhattan Bridge suspended above an immense cluster of small, bright lights, glowing like a swarm of fireflies. Neither a festive decoration nor a work of public art, this is instead a vision of a new type of cemetery for the modern, crowded city. Pods that serve as coffins would hang from the bridge’s metal skeleton; affixed to each one’s shell, a light—powered naturally by energy converted from the human remains tucked inside.

The scene could belong in a futuristic, science-fiction movie, but Constellation Park is just one of many developing ideas to emerge from DeathLab, a nine-person think tank that unflinchingly embraces the intentions of its name. Run by architect Karla Rothstein, DeathLab is currently designing and prototyping “new models of mortuary infrastructure” for New York City in particular. Urban cemeteries, Rothstein realized, are limited in terms of space and logistics, and no local, environmentally sensible alternative exists.

“People go out of their way to make New York City and other global cities their home,” Rothstein said. “So to find ourselves in a predicament where we’ve worked during our lives to live here, but we can no longer die here, seems unnecessary.”

“People go out of their way to make New York City and other global cities their home. So to find ourselves in a predicament where we’ve worked during our lives to live here, but we can no longer die here, seems unnecessary.” — Karla Rothstein, director of DeathLab

Earnest and steadfast in her convictions, Rothstein is a slight “creative thinker,” as a colleague described. She divides her time between directing the architecture firm Latent Productions and teaching design studios at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation, out of which DeathLab emerged a few years ago. The team now includes an art historian, the University’s head of religion, an environmental engineer, and some of Rothstein’s students.

Their designs rely on advanced technology that engages with and accelerates the body’s natural chemical composition. What remains after is wholly organic, and each disposition method requires a fraction of the energy cremation consumes. Such alternatives are currently not widely used, however, as research in them is still underway. In promission, a process developed in Sweden, a body is essentially freeze-dried before a minute’s worth of ultrasonic vibrations breaks it into organic dust. Resomation, better known as alkaline hydrolysis, uses heat and pressure to reduce a body to calcium ash and a DNA-free liquid in less than three hours. The Mayo Clinic has adopted this method since 2006 to dispose of donated research cadavers, and it is actually a legal alternative to cremation in some states. A third method, microbial methanogenesis, is the one Constellation Park would incorporate. In each of its suspended pods, tiny organisms would accelerate the body’s natural decomposition to transform matter into methane—already a natural part of decay. The methane may then produce energy to illuminate the attached light, which would dim over the course of the process.

Rothstein describes Constellation Park as “a collective urban cenotaph” that also functions as a public park “shimmering with imprints of intimate individual memory.” (courtesy DeathLAB in collaboration with LATENT Productions)

Unlike a traditional cemetery, which sells space for perpetual ownership, Constellation Park would “rent” out spaces to alleviate land pressures. Each vessel is reusable after about a year, and Rothstein envisions relatives scattering the organic remains or using them as fertilizer in a public garden specially designated for that purpose. Ideally, she envisions 10 similar structures around the five boroughs, which would approximately cover the city’s deaths each year.

Tinkering with time, DeathLab’s designs thus rely on upending the conviction that everyone should own a fixed space for permanent remembrance—the very appeal of the traditional cemetery model. “Most families still want some type of a place to go visit,” Ison explained. “Some type of memorialization, some place with the plaque and the name that they can go out and remember their loved one.”

But Rothstein argues that people may still form an affiliation with the site they may choose to rest remains. More importantly, she believes that ecologically friendly burials have more value to society and future generations than the purchase of an individual spot for eternity. “In this case,” Rothstein said, “what endures is the collective constellation of our respect for and honoring of the dead in order to instigate a more responsible relationship to the future.”

Suspending the dead on a functioning overpass is no minor shift from burying them deep underground, but DeathLab believes society is diminishing its commemoration of the dead by confining death practices to the city’s periphery. But far from existing as spaces for just the deceased, DeathLab’s designs reflect the early view of cemeteries as public spaces for recreation: many of them envision bike paths weaving along pedestrian platforms and past spaces that could host events.

Constellation Park would have vessels that function as “short-time shrines” hanging from a structure such as the Manhattan Bridge (courtesy DeathLAB in collaboration with LATENT Productions)

“I believe this very sincerely—that having reminders of our own mortality in our midst offers us perspective,” Rothstein said. “I think, as a society, that perspective is really essential in helping us measure the consequence of the actions that we’re taking while we’re alive.”

DeathLab may begin prototyping Constellation Park, which has received eager and positive feedback, as early as within the next year or two. Rothstein recognizes the challenge of overcoming cultural norms, but she sees the success of cremation as proof of how much attitudes may change in just 50 years. “We, in general, are an open-minded society,” Rothstein said, “and I think that the logical side of having the reduced environmental impact and a dignified, celebratory demeanor with respect to death is pretty convincing.”

It happens that Americans are thinking about death and memorialization in new ways that imply a need for visionary mortuary practices. As last year’s National Funeral Directors Association’s report found, people increasingly prefer “simple, less ritualized funeral practices.” The number of Americans who do not identify with any religion has also surged, and these unaffiliated adults are more likely to choose cremation for loved ones. Projects like Constellation Park, which would be a nonsectarian establishment, meet such shifting inclinations.

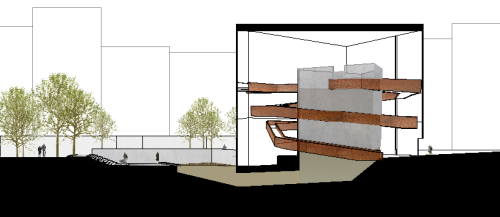

That failure to find meaning in current burial methods is why Seattle-based architect Katrina Spade launched her campaign that also seeks a posthumous connection with nature—“the closest thing I have to a spirituality,” she said. Like Constellation Park, her Urban Death Project engages with accelerated decomposition methods to offer memorialization options in the city, though in a less conspicuous manner. Her design, initially based on an actual empty lot in lower Manhattan, consists of a building integrated into the heart of the city. Inside rests a carefully engineered, “compost-based renewal system”—one that turns bodies into soil. Rather than remaining trapped and destined to rot in caskets, our bodies, Spade imagines, may return to the ground to nurture pine trees, honeysuckle bushes, or even fields of lavender. “For me, the idea of being folded back into the city after I’ve died is really appealing,” she said. “Like actually being transformed into the different material that then is going to grow new life in the city.”

Rather than cemeteries, Katrina Spade proposes facilities that turn bodies into compost. (courtesy the Urban Death Project)

Spade imagines multiple facilities in every city, like on a “library branch scale,” although she has to examine and possibly amend local legislations. In New York, according to Polishook, the city would consider removing the soil a disinterment, which is problematic. City council would also have to approve the facility if Spade intends to place one below 86th Street. But laws may be repealed and definitions broadened. More challenging may be appealing to those who find human composting repulsive or unsettling. But like Rothstein, Spade remains optimistic about society’s evolving attitudes. Her Kickstarter, which launched at the end of March, reached its fundraising goal in just one month. Urban Death Project is still in its design phases, and the money will support the second phase of engineering that is part of a “toolkit” to help communities plan their own neighborhood facilities. Emails have also streamed in from people around the world interested in bringing Urban Death Project to their cities.

Standing three stories tall, each building would function as a site for simple ritual. Mourners would carry the deceased, wrapped in a shroud, up a ramp that winds around the composting core. At the highest point, they would lay the body in the core and say their farewells. In the following weeks, the body travels through the system until fully composted through aerobic decomposition and microbial activity.

Spade has been conducting research with Western Carolina University’s human decomposition facility in North Carolina to “most effectively make a really beautiful compost mix,” as she put it. There, she and scientists test cadavers, nestling them in various combinations of carbon material to better understand the logistics and timeline of creating human compost. The process would emit no odor, as woodchips and sawdust would serve as bio-filtering mechanisms. At its end, loved ones could collect the compost, which Spade estimates would fill a three-foot cube, and use it to grow new life. The entire process would cost about $2,500, comparable to the price of direct cremation.

Spade has not yet set a definite timeline for the project’s completion, but one thing she remains certain of is that the city’s cemeteries are on their way out as realtors for the dead. “I think cemeteries are going to be a thing of the past pretty soon,” she said. “At least urban cemeteries. They’ll still exist as historic places.”

“I think cemeteries are going to be a thing of the past pretty soon. At least urban cemeteries.” — Katrina Spade, founder of the Urban Death Project

More than ever, cemeteries need to recognize that they are “marketable products” to remain economically stable, Ward wrote in his article. As Moylan stressed, Green-Wood will always be a cemetery in service of its lot owners. “But how will we survive in the future when we’re not generating millions of dollars in sales?” he asked. “How can we keep this place looking as it does now, a hundred years from now?”

Today, public support comprises a small fraction of the cemetery’s revenue. For about a decade, Green-Wood’s grounds have hosted trolley tours, bird-watching excursions, book readings, theatrical productions, and other cultural events. As visitors stream in, so do donations. But the cemetery is developing bigger plans still as it focuses efforts on existing beyond a business in death. For the past seven or so years, Moylan has been collecting artworks by artists buried at Green-Wood; paintings, sculptures, and art magazines crowd his office, already overrun by foot-tall stacks of files. In 2012, the cemetery purchased the landmarked Weir Greenhouse across the street, receiving a $500,000 state grant to restore it. If construction remains on track, the building will open in two years as an exhibition hall and visitor center to promote Green-Wood’s vault of history.

Green-Wood is far from the only cemetery forging an identity as a center for the living as much as one as a home for the dead. Ison envisions Woodlawn growing as a museum that recounts New York’s history through its past residents. The Marble Cemetery, which receives no steady income from sales, has for many years explored other profit-making methods.

Last November on a brisk, overcast Sunday afternoon, a stylish crowd gathered on its 185-year-old grounds. Few were wearing all black; there was no casket in sight, no hearse waiting near the back-alley gate on Second Avenue above Second Street. Instead, surrounded by the stone walls bearing marble plaques that name the 2,100 or so deceased buried 10 feet below them, people played pétanque and chatted over cocktails and brunch bites.

A local design company was the host, only one of many firms and individuals to rent the cemetery’s half-acre lot. Since 2000, others have organized poetry readings, dance recitals, family picnics, and a Stella McCartney fashion event. The last time the grounds served their original purpose was in 1937, for the burial of one Charles Janeway Van Zandt. Renting the site, DuBois said, is “the key to this place’s future.

“We are thriving more than we were 10 years ago,” she continued. “Each year we’ve increased the amount of lawn, which makes it nicer so we can then have bigger parties and rent to more people. Every year, we’ve doubled our income.” Last year, the cemetery made about $30,000 from rentals alone. It pocketed $5,000 from that lawn party, with remaining profits coming from several fundraisers, a wedding brunch, and four weddings—each at least earning $2,500. It also receives donations from visitors when it opens its iron gates to the public on certain dates of the year.

“It doesn’t feel like we’re in New York,” exclaimed one curious visitor to her friend as they strolled across the lawn on one of the first days of spring. Still, the city marches on beyond the cemetery walls. The demands of the living, at times, plague the lot and its permanent residents, especially any local digging and drilling that may shift foundations and shake the subterranean vaults. But DuBois can only do so much to prevent damage. For now, she plans for the coming year, when corporate events, a Hollywood film, a fraternity cookout, and many more weddings will once again transform the cemetery’s no longer forgotten grounds.

Some call it “Death Alley” for driving conditions so precarious it earned a spot on New York State’s most dangerous roads in 2007. But the narrow and meandering lanes of Jackie Robinson Parkway, which links Brooklyn and Queens, also form another kind of Death Alley. Not only does the roadway cut a nearly five-mile swath through parkland and a sprawling golf course, but it also winds through New York City’s ever more crowded Cemetery Belt. Jagged stretches of ashen headstones from over a dozen graveyards flank the route, some facing the vehicles whizzing by. Others turn to their sides as though determined to ignore the blaring sounds and reckless pace of 21st-century New York.

“GRAVES, CRYPTS & NICHES AVAILABLE,” announces a large sign affixed to a fence that separates tombstones from traffic. The notice belongs to one of the largest cemeteries in the area, Cypress Hills, a nonsectarian necropolis that has straddled the border of the two boroughs for 167 years. But Anthony Desmond, its vice president of operations for nearly three years, estimates its 225 acres will run out of available plots in 75 to 100 years. In the business of life to death, that is shorter than it sounds.

The subway trundles over Washington Cemetery, one of New York City’s first public cemeteries to run out of space. Landlocked, the city’s burial grounds are unable to expand to accommodate its future dead.

Other cemeteries around the city give themselves even less time. Four-and-a-half miles away, in the Queens neighborhood of Kew Gardens, Maple Grove anticipates only another 30 to 40 years until it has no in-ground burial space to sell. The nonsectarian cemetery currently has over 83,000 interments across its 65 acres. At Flushing Cemetery, the timeline is shorter still. If the 75-acre establishment continues selling its graves at its current yearly average rate, its inventory of plots will be gone in six-and-a-half to seven years.

“It’s something I probably worry about almost every day, at this point,” Flushing’s general manager John Helly said with a hint of weariness. “Every decision that I make, I’ve got to make sure that I’m making the best use of every piece of land that I’m taking.”

By 2040, 15.6 percent of New Yorkers will be aged 65 or older. This leap from 12.2 percent in 2010 signals a spike in the death rate. Today, of the approximately 51,000 people who die annually in New York City, nearly two-thirds choose earthen burials. But as land supplies steadily deplete, many cemeteries within the five boroughs increasingly struggle to provide space for this traditional form of memorialization, rooted in the religious practices of New York’s early Dutch settlers.

“Cemeteries: The End is Near,” Gotham Gazette warned in 2005, noting that Green-Wood’s 478-acre grounds in Brooklyn, now home to 560,000 permanent residents, was then just five years shy of capacity. And yet, five years later, under the headline, “City Cemeteries Face Gridlock,” the New York Times extended Green-Wood’s sales life by another half-decade. Today, Green-Wood’s president of 29 years, Richard Moylan, believes the cemetery has enough space to last through 2020.

As Desmond remarked, “It’s no secret. It’s out there. There are many cemeteries that are dwindling, that don’t have much space left. What needs to be done is, you have to be creative, and you have to make the right decisions to maximize your inventory.”

“It’s no secret. It’s out there. There are many cemeteries that are dwindling, that don’t have much space left.” — Anthony Desmond, vice president of operations at Cypress Hills

Throughout the city, cemetery boards have been rethinking their operations, devising innovative solutions to maximize the full potential of the land they have left to sell. With grave sales as a cemetery’s primary source of income and available plots so few, strategies that keep revenue flowing are critical for survival. Cemeteries must consider the cost of maintenance for both their dead and those yet to die, whether or not sales continue.

In the past, insolvent boards have relinquished their duties, leaving grounds to fall into ruin. With the city’s land at a premium, some developers have bought graveyards, replacing them with more remunerative structures for the living. Fortunately, new consumer trends have emerged in the death industry that demand less real estate, most notably the rise of cremation over the past half-century.

This willingness to modify the customs of memorialization to match new public preferences has proven key to the cemetery business. In the May 2013 issue of American Cemetery, David Ward, the president of a cemetery landscaping firm, noted that there have been more changes in cemetery planning in the past 25 years than there were in the whole of the previous century.

Yet, as tensions between the metropolis and its necropolises mount, critics of the modern burial industry argue that to serve the city’s dead for generations to come will take more than new models of permanent memorialization. The real solution, they contend, requires the harnessing of new technologies and innovative architectural designs. Burial practices must be completely re-envisioned.

David Ison, the Director of Sales and Marketing at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, emphasized that his team must “strategically plan,” which means staying aware of clients’ current needs while remaining open to the possibility of major modifications. “Because one thing I can assure,” he said, “is that two generations, three generations down the road, it’s going to look like something we can’t even imagine.”

“One thing I can assure is that two generations, three generations down the road, [the cemetery is] going to look like something we can’t even imagine.” — David Ison, director of sales and marketing at Woodlawn

Across the world, cemeteries in other densely populated cities have already undergone facelifts, especially those that search skywards for space. In Santos, Brazil, the world’s tallest cemetery stretches 32 stories high with coffins fitted into wall recesses known as crypts.

The challenge of graveyard overcrowding and redesign is not unique to New York, and neither is it new. But past solutions, like transferring bodies to new locations, have proved contentious and are unlikely ones for the current era. One need only glance at the sites of New York’s cemeteries to realize that efforts to find land for the dead today in the world’s sixth most populous city have reached an impasse.

Many cemeteries sit beside subway tracks or busy streets, their serene settings in conflict with the urban environment. Around the Jackie Robinson Parkway, eternal rest comes with the rumble of passing traffic. The roadway actually curves as it does because the city aimed to build around the existing cemeteries; yet, in 1930, it still disinterred some 400 bodies to use that property. In Upper Manhattan, avenues and streets border Trinity Cemetery, established in 1842 as an extension of Trinity Parish’s downtown churchyard. Thirty years later, when Broadway extended north, it bisected the cemetery, creating a valley of traffic between the resting grounds of more than 20,000 souls.

Surrounded by the living on all sides, Trinity has no way to expand on site—a familiar limitation in cemetery circles. The city’s urbanization over the past 150-plus years has left its graveyards landlocked. There are no current plans for a new necropolis, and founding one would be nearly impossible. Not one large, open tract is available. A corporation would also face legal hurdles if it wanted to purchase any property for burials, including obtaining permission from the district Supreme Court. In a city of such frantic residential and commercial development, anyone choosing to market to the dead would make poor competition.

“If I were a physician, and one of those busy men of Wall Street, who complain of the wear and tear of an unresting brain which brings sleeplessness and prostration in its train, came to me for advice, I should prescribe a daily half-hour walk in the churchyard of old Trinity.” So wrote one New Yorker, John Flavel Mines, in his 1896 recollections of walking through Trinity’s burial grounds. That “garden of the dead,” he continued, “breathes peace and healing into the tired and overworked brain.”

Years ago, particularly before the emergence of public parks, those who sought escape from urban life found relief, like John Mines, in Manhattan churchyards and the private cemeteries that the early Dutch settlers established in Queens. Once there were countless burial grounds across New York, but the demands of the city’s burgeoning population eradicated most. Two centuries ago, Manhattan alone was home to dozens of active graveyards. At least 22 lay south of City Hall, as the historian Debby Applegate noted in the collection of essays Green-Wood at 175. Today, only three active Manhattan cemeteries remain: Trinity and the two Marble Cemeteries in the East Village. All are landmarked as historical sites.

The New York Marble Cemetery occupies a lot bounded by East 2nd and 3rd Streets, Second Avenue, and Bowery. Nearby, another Marble Cemetery lies on East 2nd Street between First and Second Avenues.

Initially, a cemetery’s biggest threat stemmed from health, not land, concerns. In 1806, a report by the New York City Board of Health proposed prohibiting additional grave sites in Manhattan, suggesting that parks replace those “receptacles of putrefying matter and hot beds of miasmata.” It took another 45 years, however, for the city to ban public, in-ground entombments—albeit just south of 86th Street—an interdict that remains in effect today.

By the 1830s, interments on the island had reached an annual rate of 10,000, and the population had nearly tripled over the previous decade. People located to new, emerging neighborhoods as the city stretched north; churches, following their congregations, sold their sacred properties downtown to developers whose priorities decidedly favored the living. In a scathing editorial for the daily New York Aurora published in 1842, Walt Whitman expressed outrage at a developer who dug up bodies from a Baptist cemetery at Delancey and Chrystie streets. The incident was only one of many in the 1830s and 1840s, when the city carved out and widened streets, destroying burial grounds and disinterring their residents.

Today, disinterment remains legal, although New York State’s Division of Cemeteries’ current legislation discourages it. The Division’s laws apply to the region’s public, not-for-profit cemeteries—about 30 within the five boroughs. Those intending to remove a body from a graveyard need written consent from the cemetery; the lot owners; and the decedent’s surviving spouse, children, and parents. Cemeteries will thumb through records, peruse death certificates and wills, post notices and newspaper ads, and send letters to any last known addresses. Once found, if any family member declines the disinterment request, obtaining a court order may overturn the decision.

But in the mid-19th century, ministers could simply sign off on their deeds, said Caroline DuBois, president of the New York Marble Cemetery, which led to frequent mass disinterments of churchyards. Workers loaded carts with unclaimed bodies bound for potter’s fields and reburied thousands of others in new, verdant cemeteries that found property in Queens and Brooklyn, still, then, mostly farmland. Green-Wood, New York’s first of these vast, park-like necropolises and today one of the country’s most renowned, witnessed its first burial in 1840—the remains of four people removed from one of the Marble Cemeteries.

Green-Wood, the first rural cemetery established in New York City, boasts 478 acres of greenery today.

Observing Manhattan’s burial grounds as “teeming with dead bodies” and surrounded by “compact masses of buildings,” Henry Pierrepont and other prominent Brooklynites had purchased almost 200 acres of land in their borough to establish Green-Wood. Their vision of providing New York’s population—then around 312,000—with proper resting places in a natural and quiet setting was inspired by Pierrepont’s trip to America’s first such “rural cemetery,” Boston’s Mount Auburn.

The state, too, addressed severe overcrowding in Manhattan’s churchyards, and passed the Rural Cemetery Act in 1847, which permitted nonprofit corporations to establish commercial burial grounds in rural regions. Shortly after, a number of public cemeteries, including Calvary, Cypress Hills, the Evergreens, and Woodlawn—all still active today—opened their gates. Although city dwellers initially balked at the notion of final rest so far from their churches and ancestors, attitudes quickly changed. In his book, Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery: New York’s Buried Treasure, Jeffrey Richman, the cemetery’s historian, wrote that Green-Wood received 100,000 interments in its first 25 years, and a greater number of New Yorkers purchased large family plots for future use.

The remains of thousands of people removed from crowded churchyards eventually filled many of these new spaces so Manhattanites no longer lived in close proximity to the dead. Woodlawn’s ninth annual report, written in 1872, places its total interments at the time at 11,536. Reinterments comprised over half that number.

On a cool March morning, as a light drizzle began to fall, John Helly stood near the edge of Flushing Cemetery and gestured toward a flat field. ”This is my last open area,” the 47-year-old manager said. “I have to be able to put in as many burials as I can. After this sells out, I’m technically out of land.”

He seemed to be exaggerating because at a glance, Flushing appears to have plenty of unused space open for multiple memorials in other sections of its property. Cemeteries, however, inevitably have more vacant plots than ones for sale since many people make advance purchases, or “pre-need” arrangements. And sometimes, for whatever reasons, the owners simply never fill them. Many plots accommodate two or three bodies, stacked on top of the other. To reopen these graves, most cemeteries must, therefore, also leave sufficient space between headstones for the digging crews and their machinery.

A cemetery’s landscape may not explicitly reflect its current space conditions, but its layout often does reveal how land pressures heightened as it aged. Maneuvering his car slowly through Flushing’s curving roads, Helly first passed the cemetery’s older sections, dominated by large family plots, where headstones dating to the mid-1800s huddle haphazardly in scattered clusters. As he drove through zones more recently filled, the large, sparsely distributed lots gave way to headstones in neat, compact rows. “The land is very economical,” Helly said. “There’s no waste of land over here. Everything’s tight as it could be.”

At Maple Grove, the grounds convey a similar shift in burial layout. The earliest sections follow the style of a rural cemetery, with upright tombstones engraved with old Dutch family names tucked up on the hills, resting in the shade of large maples and evergreens. Bonnie Dixon, the cemetery’s executive vice president and general manager, explained that changes in burial planning practices have reduced the distance between markers. As the cemetery matured and expanded, it began placing its interred nearly toe-to-toe. “The days of having family plots and planning for generations are moving by the wayside,” Dixon said, “replaced by people buying more for their parents.”

Those aging, large plots, as it happens, have proved a godsend. As cemeteries design tighter layouts, the search for available land has led them to eye the empty spaces. Maple Grove, for example, owns lots with space for as many as 18 family members, but these rarely fill. Those graves would remain empty forever if not for the law that authorizes cemeteries to reclaim them. For slightly over a decade, cemeteries have had the right to sell a grave older than 75 years that was never used or that had a lawfully removed body.

Maple Grove, which runs one of the most active reclamation programs in the city, even hired a part-time employee to research potential graves for recovery. Like a disinterment request, reclamation efforts require cemeteries to locate plot owners and ask if they wish to retain their burial rights. If a thorough search for descendants proves unsuccessful, the cemetery may then petition the state to request reclamation.

Since 2005, Maple Grove has successfully recovered 206 graves, all purchased under a statutory price, set as the original price of the grave with four percent interest on the number of years the grave was owned. Cypress Hills, too, began reclaiming graves early last year that yielded a boost in inventory of some 180 individual spaces. Desmond said his team anticipates finding more.

But not all cemeteries boards support this strategy. “We don’t believe in it,” said Anthony Salamone, who now sells plots at Evergreens. “It’s not going to happen on our watch.”

Instead, Salamone, formerly the cemetery’s assistant superintendent, checks the Evergreens’ records every day for unsold family lots as opposed to reclaiming empty graves in partially used ones. His efforts have freed up an additional 120 individual, sellable spaces.

Green-Wood, to ease its reclamation process, started “Green-ealogy,” a genealogical research program that has successfully connected some descendents to ancestral graves. But its program remains relatively small: subdividing those lots requires careful consideration to avoid affecting the appearance of the cemetery.

“And that’s prime,” Moylan stressed.

Behind Green-Wood’s towering Gothic Revival-style main archway, where a colony of green quaker parrots nests in the brownstone crevices, lie 478 acres of lush parkland. Pathways wrap around gentle hills, where grand mausoleums housing generations of New Yorkers wedge themselves, their columned facades enjoying vistas of copses and smooth ponds against the backdrop of the concrete city. Obelisks with lengthy, hand-chiseled inscriptions tower beside tombstones resting beneath old trees, naked in the winter and flaming in the fall. All around, angels and classical figures, arrested in stone, watch over the dead or pose in prayer.