The hooks are bigger in person.

Four millimeters thick by three centimeters wide. I try to picture one passing through the flesh just above my knee, disappearing under my skin and emerging three centimeters away, and find I can’t.

One hook lays on my left knee, point facing inward. Johnny Pearce, piercer and suspension facilitator, compares its width with the two blue dots he’s marked. He mumbles to himself as he works, hovering around my knees. As I’m trying to sit still, I realize I’m calmer than I should be about the prospect of hanging from hooks in my skin. Maybe it’s because I haven’t actually thought about how it will feel. Each time I try to think through the experience, I stop at the piercing. I just can’t imagine the pain. Even after thirteen piercings, the memory doesn’t stick. There is an impression of it, but it’s dulled a hundred times over, a pitiful placeholder that does nothing to reassure me I can handle the next piercing (there’s always a next piercing).

Pearce erases his work more than once. His fiancée, Tamara, is co-facilitating, and hands him alcohol wipes to remove the blue ink left by the sterile surgical marker. She’s also on camera duty: While Pearce works, she shows me a photo of the marks he’s drawn on my back, one pair of x’s on each shoulder blade, just above the neckline of the shirt I’m wearing backwards. Tamara tells me they’ll make for cool scars. I agree.

After a few more minutes — I count time by the changing songs on the speaker — Pearce is done marking. He asks if I’m ready for the next step, what I think of as the first real step: piercing. I don’t know how being ready would feel, but I say yes, anyway. I don’t want to give myself time to dwell, time to shatter the unexpected calm with all-too-familiar anxiousness. I don’t feel un-ready, exactly, but there is the lingering thought that I am making a mistake, fed by the disgust and shock of almost everyone I’ve told about this.

I lay down on the pink paper covering the procedure table, the tip of my nose pressing against it. Behind me, I hear Pearce prepare his materials, tearing open the sterile packaging housing hooks and needles. Again, he asks if I’m ready. Again, I say yes, and hope I am.

Pearce tells me to take a deep breath in. Then out. Mid-exhale, the needle pushes into my skin.

I’m almost comforted by the feeling of sharp metal through flesh, the memory of a familiar waltz rushing back to me. For a few seconds, I know what pain feels like. I feel the needle pass through my skin, then tissue, then again through skin, stretching it for a moment before bursting through. I’ve pierced myself before and remember feeling the same three-step pattern in the skin’s resistance, the visceral reminder of my physicality.

My exhale turns into a sigh of relief, even as the pain spreads, diffuses into a dull burn. I know my knee piercings will hurt more, and the actual suspension will be even more painful. But the first rush of pain reminds me the anticipation is worse than the feeling. In short: I can handle this.

Body suspension is rare — but not that rare. In almost every major city, there are groups, formal or informal, who string people like me up on hooks. They are often piercers, and almost always sport more than a few body modifications.

The process is simple. You are pierced, and in lieu of jewelry a hook is placed under your skin. How many hooks, and where they’re placed, depends on preference — most first-timers start with two or four hooks in the upper back, a position referred to as a suicide suspension. Once the hooks are in, they’re attached to ropes connected to a rigging point above the ground. Slowly, slack is taken off of the rope, and then, all at once, you’re off the ground.

Yes, it hurts. But very few suspendees are drawn to pain itself — there are easier, and more effective, ways to hurt, if that’s all you’re after. Pain is unavoidable in suspension, but only one part of a larger experience.

“When you’re up, there’s a moment where the skin stretches to its maximum to hold weight,” said Beto Rea, who has been suspending and facilitating since 2003. “And it stops hurting — that’s the interesting part of suspension.”

Rea isn’t the only one to describe a paradoxical absence of pain, one that appears at what looks like the most extreme part of a suspension. Everyone who described how their suspension felt experienced a sense of euphoria or calm after getting up that overshadowed any remaining pain. That feeling, not the pain, is what remains strongest in memories, and it’s what brings first-time suspendees back for more.

For many, the feeling isn’t unfamiliar. Suspension’s pattern of painful intensity followed by a euphoric or calming release has a far more-common analogue: runner’s high, a phenomenon where a hard workout — typically cardio-based — triggers a rush of endorphins, stress hormones which block perception of pain and can cause a sense of euphoria.

“These are two sides of the same coin of intense sensation,” said Lynn Loheide, a piercer and facilitator with more than a decade of experience. “People talk all the time about pleasure so intense it becomes painful, but also pain so intense that it becomes pleasurable.”

Suspensions sometimes cause Loheide to pass out. It’s a known possibility, and analogous to someone fainting after a blood draw. Though not dangerous, losing consciousness is usually grounds to end a suspension. Loheide, though, asks to stay up.

“Passing out during a suspension feels great, and anytime I’ve had an out-of-body experience with suspension, it’s been coupled with passing out,” Loheide said. “Many different cultures write about suspension inducing a trance state, and people having communion with gods and spirits… and I fully believe that that’s occurring when people are passing out.”

Spirituality frequently bleeds into suspension. That hasn’t always been the case — during its rise in the 2000s, Rea said, practitioners focused more on process than suspendees’ personal goals for the experience. He likened it to a factory approach, one that lended itself well to events where Rea might run a hundred suspensions in a weekend.

But for Rea, suspension has always been more than the physical. At the workshops and talks he leads, the ritual and spiritual aspects of suspension are a major focus, something he hopes has contributed to the rising interest in ritual suspensions.

“Often, the spiritual part is misinterpreted as something religious, but I separate the religious aspect from the spiritual, which is more aligning your spirit and body,” Rea said. “It’s not like you suspend or do a ritual and your life is changed — it gives you information. Now you have to process, and then see how that information can help you day-to-day.”

There is no single origin to suspension. Piercing dates back to at least 11,000 BCE, and two related practices help bridge the jump from ‘regular’ piercings with standard jewelry to temporary hooks that support weight.

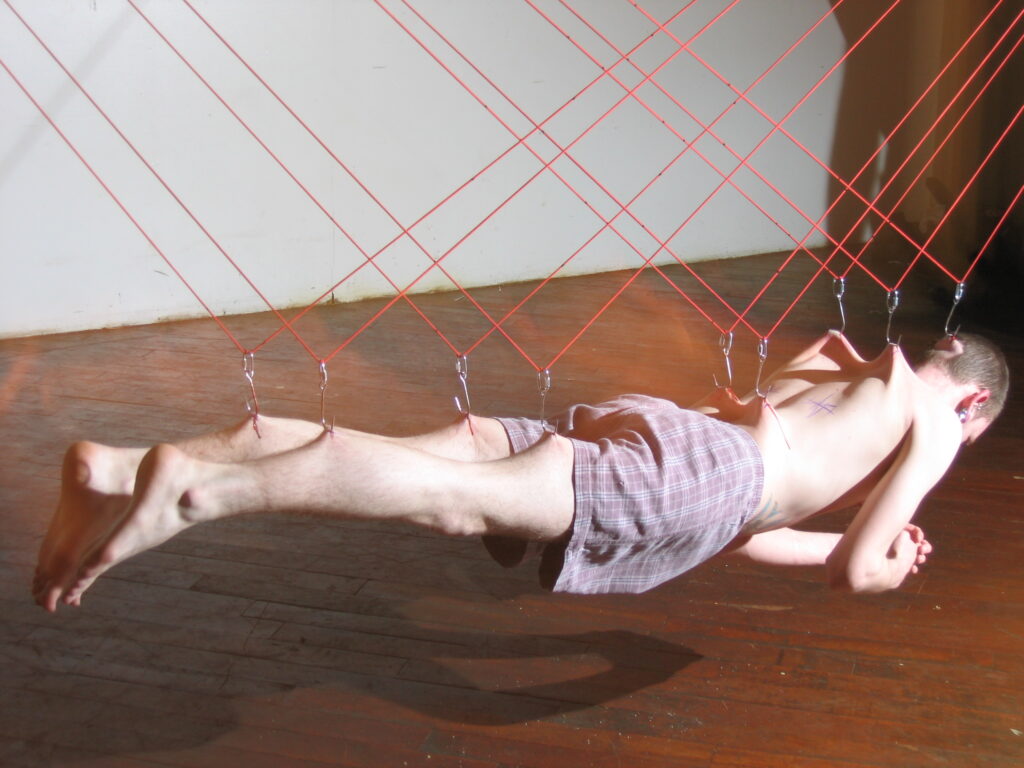

The first is play or temporary piercing, where a needle or jewelry is left in the skin for only a short period before removal. There may be a ritual purpose, but temporary piercings can also function as art. Piercers can create elaborate, decorative needle patterns, or temporary sculptures. In the kink or BDSM communities, play piercing is focused on the experience, typically in an erotic context. Historically, temporary piercing has existed worldwide, with Mesoamerican cultures like the Maya practicing forms of religious bloodletting that involved piercing their lips or cheeks. In Maya cosmology, Gods created humans by mixing their own blood with maize. Human bloodletting served as a cosmological renewal or ritual gratitude to gods.

The second practice is flesh pulling, where hooks are inserted under the skin but do not support someone’s full weight. The hooks can attach to a wall or other person — or persons — to pull against. Alternatively, weights or trinkets can be attached to the hook to create a pulling sensation.

Evidence of suspension is less wide-spread than these other practices. Some Tamil Hindus in countries including India, Sri Lanka, and Malaysia celebrate Thaipusam, a festival honoring the war deity Lord Murugan. Revelers often engage in pain penance through piercing, or by carrying heavy ceremonial burdens called kavadi. Sometimes, these combine in celebrants dragging their kavadi from pierced hooks, a form of flesh pulling. Less often, revelers suspend during the festival.

In North America, Plains tribes incorporate suspension into ritual. Among Plains tribes such as the Mandan and Sioux, a ceremony called the Sun Dance involves young men undergoing cleansing practices such as fasting before suspending or flesh pulling for multiple days as an offering for prosperity of their people. Tribes from across the plains region gather in mid-summer to practice the ceremony, the most sacred in their ritual calendar, as one.

While the Sun Dance is a living practice, its history is intertwined with attempts to kill it. The Sun Dance and other Indigenous religious practices deemed “heathenish” or “evil” were banned by the 1883 Code of Indian Offences. The Code also sought to end traditional medicine, social organization, and property practices, deeming all “injurious to the Indians and so contrary to the civilization that they earnestly desire.” Violations could be met by withdrawal of rations, or incarceration for up to 30 days.

Criminalization wounded, but could not kill, the Sun Dance. In addition to witness accounts and oral tradition testifying to the resilience of these ceremonies, there are rare photographs depicting them, including a c. 1909 photograph of a Cheyenne Sun Dance in Oklahoma.

It took until 1934 for the Code to be reversed by a new Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Religious liberty for Indigenous Americans wasn’t affirmatively protected until 1978, with the passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.

But in 1967, before that protection, another Sun Dance took place, one that would become pivotal to today’s suspension movement. Its sole dancer had little to fear from the Indian Affairs Bureau — for 37-year-old South Dakotan, Roland Loomis, the ritual was not a communal ceremony, but an early experiment in what would become a revered body modification legacy.

Loomis would first use the name Fakir Musafar in 1977, for a performance at the first international tattoo convention. Its organizer, wealthy patron of modification Doug Malloy, thought Loomis’ given name was too unremarkable. His stage name, Fakir Musafar, honored a 12th-century Sufi Loomis had learned about in a Ripley’s Believe it or Not newspaper comic, who purportedly said one should pierce oneself to become closer to god. The name stuck.

If one person is to be associated with today’s suspension movement, it’s Fakir Musafar. He is so well known that many refer to him only as Fakir — in this world, he has the same one-name status as Beyoncé.

It was Musafar who coined the term Modern Primitive, describing a movement seeking to create body-mind connection through rituals involving “body play,” such as suspension or play piercing.

It was Musafar who began training others in suspension, a mentor-apprentice-client relationship common in body modification and which creates a lineage tying almost everyone involved in suspension back to Fakir. Musafar’s 1985 film, Dances Sacred and Profane, marked the first time many would see suspension. His death in 2018 was a blow to many in the community, one marked by some with their own Fakir-inspired rituals.

But despite the reverence with which his name is often spoken, Musafar is not an uncontroversial figure.

“That man is untouchable — but if you, with actual perspective, look at the process, it is literally the definition of cultural appropriation,” said Julie Landry, founder of the First Nations Hook Collective (FNHK). “When you see the old pictures when he did the Sun Dance-thing, there’s almost no mention [of origin]. It’s a complete erasure of where it comes from.”

Landry, a member of the Wabanaki Nation, is one of multiple suspension practitioners working to integrate Indigenous perspectives into the contemporary suspension scene. With more widespread conversations about cultural appropriation, today’s suspension practitioners tend to frown on explicit attempts to use Indigenous suspension rituals in the way Musafar did. The goal of the FNHK is to bring together Indigenous suspension practitioners and lead community conversations about the historical and ongoing Indigenous influences on suspension.

“We need to have something where all the different Indigenous perspectives on the practice can merge and re-appropriate the narrative,” Landry said, “so it’s not settlers talking about us and our practice, but it’s us talking about us, because we’re able to do it. We’re able to speak for ourselves.”

Landry doesn’t believe that the practice of suspension belongs to a single group — it’s just another tool for ritual, she says, which itself is present in every culture worldwide. The goal is not to freeze suspension in some imagined historical state, but to include Indigenous voices in building the future.

“This is not modern this or that, this is a new in-between,” Landry said. “That’s where the conversation seems to be: Indigenous people wanting to reappropriate the narrative and talk for ourselves, and really create this circle between the hook suspension scene and the modern primitive thing.”

Throughout the 1980s and `90s, Musafar mingled with people who were, or would become, modification royalty. He worked with Jim Ward, founder of The Gauntlet, the United States’ first professional piercing studio, which opened in 1978. Musafar met and taught suspension to Alan Falkner, a now-renowned piercer who would create the first suspension group, Traumatic Stress Discipline, in 1992, and in 2001 organized the first suspension convention. Separately, the performance artist Stelarc suspended more than 20 times throughout the `70s and `80s across the United States, Germany, Australia, and Japan. In 1984, he drew a small crowd by suspending over New York City’s E. 11th St.

It was the early 90s, and suspension was beginning to gain steam. It was about to gain more. In 1994, the first online publication dedicated to body modification appeared: Body Modification E-Zine, which expanded its scope to become a social media platform of sorts and ran until 2022, when owner Rachel Laratt passed away — Shannon Laratt, her ex-husband and BME creator, had died nine years before. The site remains offline. But BME lives on — and not just in the hearts of those who found community on its message boards or at now-legendary BME meetups. In 2024, the inactive @bmezine Instagram account posted for the first time in years. The account began posting fan-submitted modification photos, like the old site’s submission page. Months later, it announced a 30th anniversary event in New York City, the first in years. The accompanying illustration features a lizard crawling out of a grave with a marker reading “BME 1994-2024.” A speech bubble floats next to the lizard, making a single promise — “not yet!”

My second back piercing goes quickly. Pearce is skilled at using the needle to transfer the hook under my skin, so quickly I hardly feel it. The worst is yet ahead, but I’m feeling better with each hook.

When I sit up, the Gilson hooks attached to me tug on my skin, unexpectedly heavy. Pearce asks me if I want to keep going. I could hang by back hooks alone, like most first-timers do, but it always looked uncomfortable. I imagined my arms would feel restrained, that I would find it hard to breathe, and I would panic. I had asked everyone I could for suspension advice, and many told me the same thing. As Landry put it: “If you look inside, what resonates? … Follow that fiercely.”

So I take the knee hooks. I look away while Pearce pierces me — I don’t like to see pain coming. I look everywhere else. The clock on the stovetop marks 4:41. On the kitchen wall, a chalkboard decorated with Gilson hooks reads “hooked on a feelin’.” Piercing goes quickly, and suddenly it’s done, and I’m still calm.

Pearce and Tamara congratulate me, tell me I was tough and took the hooks well. I’m emboldened by how easy it all felt, but acutely aware there’s little standing between me and actually suspending. Pearce asks if I’m ready to step outside and get connected to his backyard rig, a lighting truss he’d prepared with the hardware to support the position I would suspend in. He suggests I do it as soon as I’m ready — the longer I wait, the more opportunity there is for adrenaline and endorphins to wear off before the real pain even starts.

It takes me a moment to register that I’m being asked to walk. I look at the obscene hooks in my knees. I don’t want to move them. I don’t think I should. I feel the hooks with every twitch, the alien, unfeeling metal holding rigid against soft tissue. Slowly, I straighten one knee, just a little. The hook moves with me. Uncomfortable. But not unbearably so. Gingerly, I slide off of the procedure table. I take small steps to the back door and walk stiff-legged down the few steps to the back yard. I sit in a foldable white chair Pearce has set up under the truss — he had measured and cut ropes to length before piercing me, so all that’s left is connecting my hooks, me, to the rigging. I cringe at the feeling of my knee hooks sliding as I sit down.

I keep my eyes closed as Pearce works. It’s cold, and I regret wearing only one pair of leggings. Occasionally, I hear Pearce warn me something will be uncomfortable, like turning my hooks to the right angle. Every few minutes, Tamara presses clean gauze to my wounds to stanch the bleeding. My right inner shoulder wound bleeds prodigiously. When blood begins to drip down my back, it feels cold against my skin in the chilly sunset.

My music stops. It flickers in and out for a moment before turning off completely — the speaker is out of range. Tamara offers to bring it closer, but the sudden silence feels right.

I’m connected. Each of my hooks is attached by rope to a metal rig plate above my head. The plate is attached to the truss with a pulley. Pearce asks me if I’m ready to get started, and I say yes almost immediately.

Tensioning starts by taking all the slack off of the ropes, enough for the hooks to stand upright without stretching the skin. Using the pulley, the rig plate is slowly lifted in small increments. It’s normal to need adjustments: at first one hook’s rope might be too loose, or the angle might be off. Eventually, though, each hook should feel about equally (un)comfortable.

Now, there’s no prep left. I rock slightly against my back hooks: a dull burn sharpens the harder I pull. Like Tamara warned, my knees are worse. The pain starts at a vibrant intensity that climbs quickly with more pressure. I ease off. It’s my call when to start and stop adding tension. Rocking against the hooks helps me acclimate faster, reach the point where pain plateaus. The cold drives me forward: I don’t want to spend more time outside than I have to.

It is deeply, viscerally unpleasant. The skin around my wounds burns. Not like heat, but like the flood that follows the instant of stubbing your toe, or slicing your finger open on a kitchen knife. It lingers, seems to trickle in after the white-hot flash of injury. I am still in the chair. Every increase in tension pulls my skin further from my body. Eventually, my skin will have no stretch left and I will hang from it, but between me and suspending is an intimidating amount of pain. Adding tension irritates my wounds, sometimes freeing another icy drop of blood to flow down my back.

The position I’m suspending in, a chair, is one of Tamara’s favorites. She teaches me how to transfer weight from my knee hooks to my back. I’m immediately more comfortable. I slowly allow my knee hooks to bear more weight, and the gradual increase is easier to bear. Time for more tension.

I don’t know how much time or how many tiny, stepwise tension increases it takes, but eventually, Pearce tells me I’m almost up. I can feel he’s right: my knees are high enough that only my toes brush the ground.

Because of the position I’m in, I don’t get the luxury of a smooth transition: if I were standing, I could choose when to pick up my feet. I could stand on one leg, on tiptoe, until I felt ready, though I’m not sure I’d prefer that. In the chair position, no matter how minutely Pearce adjusts the tension, a larger jump in pain is unavoidable. It can only be portioned out, spread thin enough to go down easier. I tell Pearce I want the next pull to be the last.

It feels too easy. I’m still not celebrating, still apprehensive, waiting for the other shoe to drop, for the pain I have been fearing for so long to consume me.

I don’t feel myself leaving the chair. The final pull is a wall of pain that shrinks my consciousness down to my hooks. It’s more than I expected, longer than I expected. There is no better way to describe it: my skin is being pulled away from me by an open, bloody wound. I want to call it unbearable, except that I’m bearing it, and without the panic, the tightness in my chest, the sheer anxiety I expect from myself. The pain reaches a plateau and stays there. I breathe and focus on feeling.

A core tenet of Buddhism is that all suffering stems from desire — you suffer not from the injury itself, but from the desire to flee pain, itself just sensory input. I have been practicing: for weeks, whenever I’ve knocked my elbow or stubbed a toe, I have tried to feel. To feel the moment after impact, the raw hurt. To feel the seconds after that, as the ache builds and diffuses like a ripple in a pond. Just another sensation, like cool water running over my hand or my cat’s fur brushing against my leg. I don’t know how, or if, my preparation helped. But as I feel, and breathe, and feel, and breathe, the pain mellows, undoubtedly present, but receded enough to allow me to think. It has been just a few seconds.

I open my eyes. The ground is further away. Tamara is to my right, her head at my chest level. I’m up. I realize I’m grinning, and let out an excited half-shriek. The pain is still there — how could it not be? — but I am experiencing the furthest thing from suffering. Someone asks me how I feel, and I say amazing. Intermittently, Tamara is wiping blood from my back. With only hooks and skin supporting me, it feels like I could be floating. It’s strange, and I say so more than once, but I don’t dislike it at all.

Tamara is discussing something with Pearce. I close my eyes and lean my forehead against the ropes in front of me, the ones connecting to my knees.

I’m happy. Not euphoric, like some people describe, but deeply, unflinchingly content. Serene. I’m sure there is pain, but it doesn’t register. Tamara checks on me, makes sure I haven’t passed out, but is happy to give me the space to experience this. Pearce ties off the main rope securely, and he and Tamara take shifts keeping an eye on me.

Thoughts flit through my head. None of them linger. It’s quiet, for Brooklyn, and the occasional sounds of a door closing or a barely-audible conversation feel good, as if they are connecting me with the world. A car drives by playing a song from my childhood I remember but can’t recognize. An occasional breeze makes me remember that I don’t like the cold, but it’s hard to be bothered.

Eventually, a growing awareness of discomfort stirs me from the utter calm. My right knee hurts. Not the skin, but the joint, stiffness from a strange position. I try bending it, but again, it feels wrong. I argue with myself about whether I want to come down.

Finally, I open my eyes. It’s darker than I remembered, solidly past sunset. When I ask, Tamara tells me I’ve been up for an hour.

The first suspension convention took place in 2001, in Dallas, the hometown of Musafar protegee Alan Falkner. Its existence was a mark of suspension’s growing popularity. In the years that followed, more annual events sprang up, like Midwest SusCon in 2003, as well as one-offs. On BME’s events page, suspension events were listed alongside tattoo festivals and more casual get-togethers as early as 2002.

It wasn’t easy to suspend in the early 2000s. There were far fewer groups scattered around the globe, meaning aspiring suspendees had to travel for the experience. For suspension veteran Jason Shaw, who first suspended in 2001, that meant a nine-hour drive from Ohio to Toronto, first for a flesh pull, and again two months later to suspend with iWasCured, a local team.

“It was the only opportunity I had,” Shaw said. “And then that became a pattern of every three or four months, coming up to Toronto to do suspensions.”

Shaw discovered suspension, like so many others, on BME. He began using the site in 1997, and for years read every single article posted to the site — typically between 15 and 20 each week, he said, covering different modification topics, including personal suspension experiences. By the time he first went up, he had read about dozens of suspensions — but an experienced facilitator warned him to discard all assumptions.

“[He] was really adamant to try to enter it with no expectations,” Shaw said. “Do your best to just accept the experience as it happens, rather than trying to shape it into something that it might not be, because that’s a recipe for disappointment.”

His first attempt at suspension lasted only a few seconds — he was suspending with four back hooks, two of which felt pinchy and restrictive. After some troubleshooting, though, he went back up with only two hooks and had the chance to swing and spin and feel “elated.”

While Shaw was able to find a team, others weren’t so lucky. A lot depended on geography. Suspension grew by something Shaw called the “fight club effect”: someone from a particular city travelled for suspensions, then returned home to found their own team — like Shaw did in 2002. But people are only willing and able to travel so far, even for suspension, meaning that this growth radiated outward from suspension hotspots like Toronto.

For Beto Rea, a piercer, the diffusion wasn’t fast enough. He had wanted to suspend since 1999, after learning about suspension from BME and Fakir Musafar’s writing. While living in the United States for four years, he looked for people who could suspend him. It would be hard: he estimates that there were only a few dozen suspension practitioners worldwide at the time. After, living in Canada for eight months, he thought he had found someone — plans fell through. In 2003, now in Guatemala, Rea finally decided he would suspend himself.

“I started making my own equipment, working off of the photos I’d see on [BME],” Rea said. “At that time, in Guatemala, it was hard to find large-gauge needles, so I went to a vet and found needles for injecting horses.”

Suspension hooks were even harder to find — you couldn’t buy them at all. Instead, the go-to was deep sea fishing hooks, which would be de-barbed before use with a Dremel, angle grinder, or belt sander, and then re-polished. Though hooks are commercially available now — Rea himself sells them wholesale — some teams continue to process hooks the old-fashioned way, at least for part of their supply. But in the time since Rea first suspended, the technical side of suspension has changed drastically. There are new types of hooks: Gilson hooks and black sheep hooks, both of which are fully enclosed, meaning that they can’t slip out mid-suspension. Suspension groups discovered that some equipment designed for climbing, such as pulleys or rigging plates, could double as suspension gear. And beginning in the mid-2000s, the focus of suspension began to change from simply suspending to creating elaborate, multi-hook arrangements.

It started in 2005 with Oliver Gilson, the designer of the Gilson hook. He knew computer-aided design, and began using it to create line drawings of complex, many-hook suspensions. Suddenly, it was much easier to calculate how much rope you might need for an elaborate set-up, or visualize the best hook placement. Into the 2010s, suspension facilitators used their new capabilities to create human art pieces, or simply push the limits.

While Shaw was impressed by many of the complex suspensions he was seeing, the artistic focus didn’t resonate with him. Though Shaw had found community in suspension, a sense of belonging, he began to feel that his skillset was becoming less relevant. Ultimately, he chose to step back from suspension. It had become draining, more draining than a hobby should be, and he felt that the direction the community was going was a sign to move on, to accept that things had changed.

There was another reason, though, that Shaw and other experienced practitioners chose to step back from suspension, or at least become more private about their practice. In the mid- and late 2010s, people in the body modification industry began speaking up about long-standing issues. The tattoo industry experienced its own #MeToo movement, with victims speaking out about sexual assault and harassment starting in the mid-2010s, though 2020 saw a surge in reports as the Black Lives Matter movement reignited conversations about social justice. The suspension community, too, was rocked by accusations of abuse and assault.

“So many people were so hurt by the actions of people who they trusted and considered friends, or trusted with their bodies,” Loheide said.

Even those who were not directly implicated felt the impact — for not realizing sooner, or for allowing those accused into the community in the first place. Some teams simply dissolved. Others did only private suspensions, eschewing conventions altogether. American annual conventions started to die: the last Dallas SusCon was in 2017. MECCA in Omaha held on through 2019. And then COVID-19 hit.

“Nobody was doing suspensions for two plus years — and I think that was the best thing that could’ve happened,” Shaw said. “It weeded out people who were not as passionate about suspension… and gave younger voices an opportunity to step in and create a new community, that they want, in their image.”

It would take five years for the new community to coalesce. Outside of North America, suspension events rebounded more quickly. In Germany, international body modification event BMXNet came back with suspensions in 2021 — masks required, of course. Oslo SusCon also came back in 2021, though smaller and held outside. The year after, Italy SusCon came back.

In North America, facilitators noted the lack of community-building or educational suspension events. In 2024, a group of them, comprising the year-old Ontario Suspension Collective, decided to act: in 2025, North America would once again host a suspension convention.

The Ontario Suspension Convention took place over four days in March, 2024, at a rented film studio in Hamilton. About a dozen rigging points had been attached to ceiling beams, and two metal cubes lined with attachment points served as a site for more intricate rigging endeavors. The two rooms of the studio each held a short row of procedure tables, the walls behind them lined by tables stacked with suspension equipment: piercing needles, gloves, gauze, bandages, masks, marking pens, and disinfectant. In one room, rows of chairs faced a projector and screen: mornings were for classes, and afternoons were for suspensions.

Kevin Donaghy, lead organizer of Ontario SusCon, was surprised by the enthusiasm the event received. Expecting at most 60 people, Donaghy and other OSC members involved in planning eventually had to close registration early: over 110 people had signed up for the first North American suspension convention in years.

“The response from the suspension community has been phenomenal,” Donaghy said. “I think that’s in large part because people had been saying to each other for a really long time in the suspension community that there’s no educational events or skill-development-focused events happening in North America.”

On the morning of the first day, many arrivals found familiar faces. It may have been months or years since their last meeting, but the suspension community is small: eventually, you’re bound to run into each other again. And the bonds some form within the community become central to their relationship with suspension.

“Even to this day, the thing that draws me most to suspension is the people involved,” Donaghy said. “It’s this really tight-knit community of really wonderful people.”

In a convention setting, suspensions become a community experience. They create chances to meet new people: facilitators work in shifting groups to share their expertise, or learn from someone else’s. For the suspendee, who may or may not be a facilitator themselves, a convention suspension requires a certain vulnerability. The team facilitating them may be strangers. Some of those who stop to watch certainly will be.

But because this is a suspension convention, those who watch look through a different lens — they’ve seen a suspension before, if not suspended themselves.

The suspensions at Ontario SusCon were more moving than I expected. I watched one person — who I later found out was a first-timer — take unsteady steps, testing the feeling of the hooks in their back. They “walked into” their suspension, taking small steps back and forth.

With each cycle, the rope was pulled, forcing more weight onto the hooks. Eventually, they were on tip-toe. I mumbled something about how close they were to getting up, as much to myself as anyone near me. They took a final step backward. Before their foot hit the ground, the rope was pulled, lifting them just a little higher. They were up. I saw them smile and then laugh as they began swinging wildly, flying. I smiled with them and felt myself tearing up. I clapped and cheered with the rest of the small crowd that gathered. It didn’t matter that I never had, or would, speak to the suspendee.

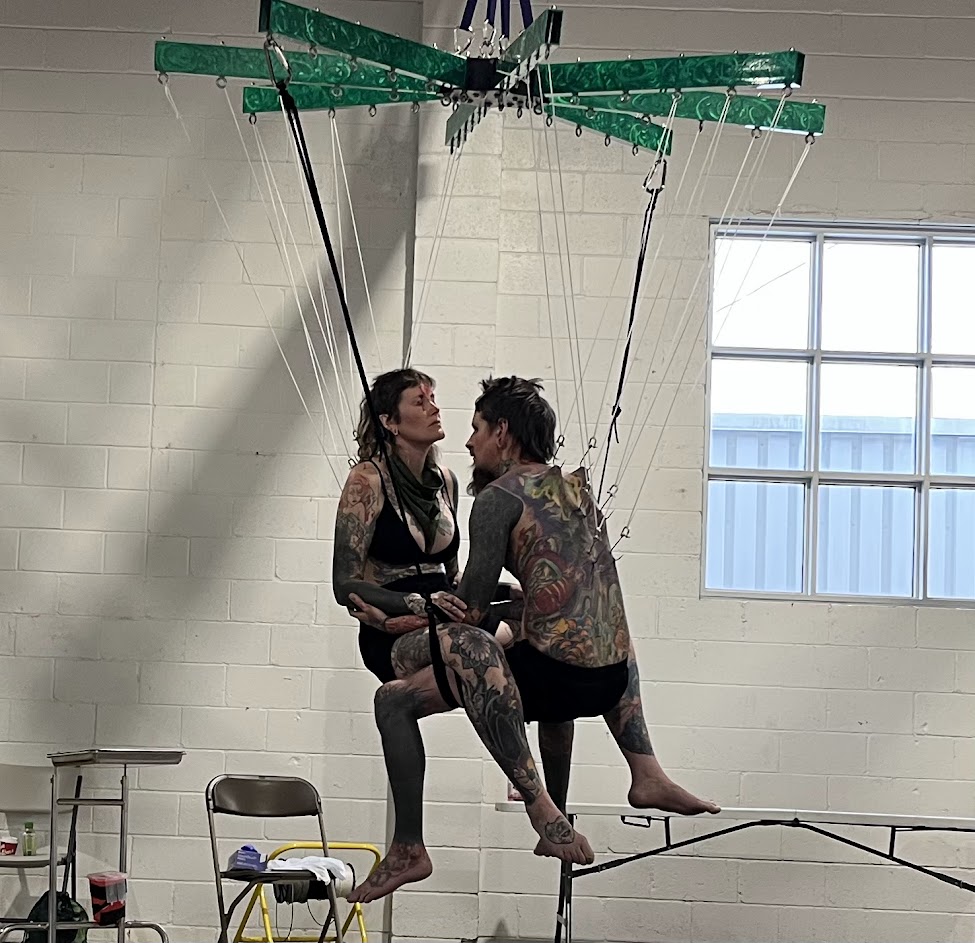

“You absorb that energy, you can feel the essence of those people in your space and that makes it all part of such a beautiful experience,” said Rossie, whose suspension with her partner, Norman, also drew a crowd. “I didn’t need to look out to see all the people around me to know that I had so many people there watching with love and care … it’s part of the magic.”

She and Norman, both piercers, did temporary piercings on each others’ foreheads, leaving the needle inserted. During a still point in the suspension, between the spinning and swinging, each removed the others’ needles, leaving blood to drip down their faces for the rest of the suspension. They looked to be in their own world, only briefly re-entering ours to ask for more swing, or spin.

“Obviously, it’s a very intimate experience, it’s really bonding,” Norman said. “But there’s a complicated element to it. When you suspend, you’re on your own time. Everyone sinks into their hooks at a different speed … but when you’re suspending with someone, you’re up in your head with, ‘am I ready when they’re ready?’ … there’s a real honesty that’s required in the communication.”

Beautiful, moving suspensions are only one side of what suspension can be, however. The other is fun, almost absurd suspensions — like a spinning double ass-tronaut.

An ass-tronaut is a suspension position where hooks are placed in the buttocks, allowing someone to hang upside down. A spinning double ass-tronaut features two people hanging from opposite ends of a freely spinning bar. There’s no codex of suspension configurations the name comes from — it could very well be called something else. But at Ontario SusCon “spinning double ass-tronaut” was enough to get the message across.

There were at least two attempts at a spinning double ass-tronaut at the convention, one successful, the other aborted after one person began tearing. In both, despite the pain, despite the tearing, the mood was light. There was laughter. This is a side of suspension that those outside the community find puzzling. For many, it’s hard to combine the idea of pain, needles, hooks, and blood with fun and laughter. But for some more-experienced suspendees, it feels like a natural progression.

“People start getting creative,” said Whittney Matlock, who runs suspension group SuspenDC. “A year ago, we had two friends of ours dress up like clowns on a seesaw rig and swing and kick each other as they’re being lifted off the ground … it was ridiculous.”

And so were the spinning double ass-tronauts. But the people involved in ridiculous suspensions are also often those who have had powerful personal or spiritual experiences on hooks. Suspension is what someone makes of it, a fact clearly on display at Ontario SusCon. There were cathartic suspensions, ones where facilitators asked those nearby to speak in hushed tones, alongside wildly swinging, push-your-limits suspensions — one man picked up two people while suspending, which led to a bent hook.

I hadn’t planned on suspending at the convention, but seeing so many people on hooks convinced me. Within an hour of deciding I would suspend, I was getting pierced. This time, I suspended from my elbows: my clothing left only my arms exposed. I knew elbows were said to be painful — they are — and was prepared for this suspension to fail. I thought it would. Each time I tried to pick my feet up, the intensity of the pain made me immediately return to the ground. My facilitator, Charlyne Chiappone, eventually had me walk into the suspension. It worked, and even though the pain didn’t dissipate, I was surprised and elated to be up. I was dimly aware of people clapping for me. It felt good. I had been welcomed into suspension spaces. But publicly experiencing the self-doubt, pain, struggle, and, finally, joy of suspension with the support of the then-strangers suspending me, I felt like I belonged. I was up for a few minutes at most, but the suspension was no less impactful than my first.

According to Donaghy, and attendees I spoke to, Ontario susCon was a success. Old acquaintances reunited, and new ones were made. The younger generation of practitioners had brought the fractured community back together, even if only for a few days, and created the type of educational event that had been missing for years. It felt like a beginning.

“They made something beautiful out of something that I had sort of written off,” Shaw said. “That part of me had accepted that I’m older now, and that that is no longer my world. But that weekend really showed me that it can still be my world, and that I’m definitely still welcome.”

Suspension is, of course, dangerous. But for different reasons than you might expect.

One concern – often the first that comes to mind — is the skin. It doesn’t seem possible that it could bear a person’s weight. But, most often, it can. In fact, it can hold more: you can pick someone up during a suspension, or have them hang from you in a tandem suspension.

Certain areas of the body are known to have more delicate skin, including knees and elbows. This can allow the hook to begin to pull through the skin and widen the piercing channel — something known as tearing. It’s not an emergency, but it does usually mean the end of a suspension. Sometimes, the problem hooks can be removed if someone wants to stay up longer: had my knees noticeably torn, for example, I could have chosen to go up by my back hooks alone.

Depending on the size of a tear, sutures may be needed. It’s subjective: sutures may not be needed for a tear to heal, but they can help minimize scarring. Many suspension teams have at least one person who can suture, so there’s no need for even an urgent care center.

Infections are also a risk, as they are with any piercing, though proper aseptic technique and wound care can substantially reduce the risk.

What’s more dangerous is falling. Today, many suspension teams and events require someone to wear a harness if they’re going above a pre-specified height, or if they’re upside down. But that hasn’t always been the case.

On May 10, 2019, tattoo artist, motivational speaker, and then-suspension performer Robbie Rippoll fell about 10 feet during a performance. He had gone through his familiar routine: he’d get pierced then give a motivational speech. He’d strip down to his underwear — donut-patterned on the day of his fall — get clipped in, and put on a show.

“I’m a motivational speaker — it’s part of who I am — and I’m a maniac,” Rippoll said. “So I would put those two together and do that. And people loved it.”

Rippoll loved it, too. The challenge, the overcoming, the decision to run toward something that scared him. But on the day of his fall, his facilitator used a rope too weak for suspension. Rippoll still doesn’t know why.

During his performance, Rippoll climbed one of the arms of the A-frame structure he was suspending on, did a pull up, and let go. He was expecting a now-familiar pain: his hooks would catch him, the audience would cheer, and his show would go on. It didn’t.

Rippoll’s fall shattered the bones in his lower leg. During his healing, he got an infection so bad he feared for his life. Rehabilitation didn’t seem promising — less mobility, pain. Seven months after his injury, Rippoll made the choice to have his right leg amputated below the knee.

A little over a year later, Rippoll suspended again.

“It was never suspension’s fault,” Rippoll said. “It’s a weird thing. I don’t understand all of it, but I knew I was going to get back to it again. I just knew it was going to be different.”

The return wasn’t a one-time thing. He’s done another suspension since, and has his next planned.

Rippoll partially credits his outlook to a friend, Jimmy Pinango, who in August 2008 fell over 20 feet during a stunt suspension performance, shattering both of his legs in front of a crowd of about 2,000. A piece of equipment connecting rigging had failed (it’s no longer used). The injury led to an ICU stay, but it only held Pinango back for so long — he suspended again in early 2009, at Dallas SusCon.

“As I got better, I tried to get back into it,” Pinango said. “I was able to go to SusCon… and that was my first suspension back, in front of the whole community. It was pretty awesome.”

Pinango and Rippol’s suspensions were very different: Pinango was suspending from a crane on multiple break-away bungee cords, Rippoll from a familiar A-frame. What unites them is that their injuries are a worst-case scenario in suspension (there’s no record of any deaths). But even after the worst, something brought them back.

There are a few questions people tend to ask when discovering suspension — does it hurt? (Yes.) Is it dangerous? (Kinda.) Is it a sex thing? (Rarely.) — but one requires a longer answer: is suspension self-harm?

It’s not a question specific to suspension. Body modification practices considered ‘extreme,’ such as branding, scarification, or tongue splitting, are also suspect. And technically, all of these do involve a form of harm to oneself. But that’s not really the question. The concern is about disorder or illness, about whether a potential suspendee is doing it for the ‘wrong’ reasons, and, implicitly, if we should stop them.

Though there are varying definitions of self-harm used in psychology, the central concept remains the same: it’s a deliberate and direct injury to one’s body without accompanying suicidal intent. Again, there is disagreement on the motivations behind self harm, but meta-analyses identify a few motivations that consistently appear in research: most strongly, a desire to control how one feels, but additionally self-punishment, to stop dissociation, or release tension. Often, self-harm will serve more than one function. For most, the act of self-harm comes after a rising negative feeling, such as anxiety, anger, tension, or dysphoria, that feels uncontrollable. Those who experience it sometimes describe self-harm as an addiction, and their frustrated efforts to stop as relapses.

While suspension does share a superficial similarity to self-harm, the emotional states involved seem markedly different. Valon Oddity, a long-time suspension practitioner who has self-harmed in the past, was skeptical about suspension being used as a form of self-harm.

“I can’t see someone going through everything that they need to go through to get the [suspension] to happen,” Oddity said. “I could easily just go and grab a razor blade or a scalpel or whatever and just cut my arm … but to do a suspension, it’s very much a ritual experience.”

Further, there are many who vouch for the positive effects suspension has had on their mental health. Often, suspension is an experience of overcoming pain, something which can be powerful for those who feel it all too often.

“When I did my first suspension, I was really struggling with depression and suicidal ideation, and didn’t really feel like I had a lot to live for,” Loheide said. “Doing that suspension and coming down and thinking, ‘What will I do next time?’ was, I think, the first time since I was a very young child that I thought about or planned for the future … suspension became the thing that made me want to stay.”

Loheide said suspension saved their life. It’s one of the reasons they’re so passionate about sharing the experience with others. Even in daily life, a reminder of their suspensions is a reminder of strength that makes difficult things a little easier — moving to a new city, presenting at a conference, confronting grief.

Landry, of the First Nations Hook Collective, sees suspension as a powerful tool for both personal healing and community building.

“I was a complete drug user, and I stopped using hard drugs because of hooks,” Landry said. “I’m not hurting myself anymore, but I’m using this bizarre skill of enduring pain to create a ritual and to create sense and meaning and healing.”

When she first saw a friend suspend, Landry said, she felt almost called to suspension. Since that day, she feels like she’s where she’s supposed to be when she’s facilitating, or suspending herself.

Landry and Loheide were also among many suspension facilitators who expressed frustration at how suspension is viewed as deviant, when other painful or potentially dangerous practices aren’t.

“If you talk about plastic surgery, you can have a reconstruction and have some super intense surgery — people can be healing for months, gigantic scars, all of that,” Landry said. “This is all fine. But if I put two holes in my back and I go up for a couple of minutes, I’m a deviant?”

It’s not an uncommon feeling in the body modification community. Even with piercings, there can be drastic differences in perception based not on danger, but on connotation — earlobe piercings are normal, but lip piercings can lock someone out of certain careers. More broadly still, our idea of what body modification entails has baked-in cultural caveats. Dyeing or cutting hair is a modification to the body, but not often considered as such. Plastic surgery itself is surgical modification of the body, but again, left out of discussions about body modification.

The distinctions drawn between these practices matter — most especially when they come to impact legality. In Nevada, suspension is considered extreme body modification, and thus illegal unless performed by a medical professional. Functionally, it’s a ban. Other extreme body modifications covered by the law include amputation, penis splitting, castration, and circumcision. These are permanent surgical procedures, while suspension is temporary: its “extremeness” is less about the tangible impact of the modification than the perception of it. Similarly, in Georgia, suspension and play piercing are completely banned alongside foot binding and surgical modifications like tongue splits.

“We have certain common values in society: what is regarded as beautiful, what is regarded as good for people,” said Dr. Thomas Schramme, a philosophy professor at the University of Liverpool. “Once we say this is cosmetic surgery, and the other one is mutilation, we’ve already decided something — we’ve made a value judgement.”

Suspension is deeply tied to ritual. There are small rituals, like the common instruction from piercers to inhale-exhale-inhale-exhale before a piercing, but the intensity of experience creates room for the creation of larger rituals imbued with deeper meaning.

“Ritual, from my perspective, is about me, the individual, making meaning out of the moment,” said Matlock, of SuspenDC. “An experience is what happened at the moment, and then the story you tell yourself about it after it’s over. Ritual is one way of managing that story.”

Matlock is pagan, and approaches ritual with a liberal mind: any experience can become a chance for spiritual meaning or connection — everything has the potential to be enlightening. He takes that approach to the suspensions he facilitates with his husband, Willow. Props and music are tailored to create the experience the suspendee is looking for, whether it’s a ritual or a clown fight. While suspension is deeply meaningful to him — he and Willow were married on hooks — he’s also happy to “hold your beer and let you fly.”

The ritual aspect of suspension is a draw for many, some of whom see it as a way of balancing the lack of rituals in ordinary life.

“Here in North America, for people like myself, the only rituals that we really have involve a piece of paper,” Norman said. “A lot of what keeps me coming back to [suspension] has been the human need for ritual in modern society that is devoid of what I consider to be any sort of meaningful ritual … it’s just a way for me to mark and measure my life and the meaning in it.”

Norman said the drive to create his own rituals is part of the motivation behind other body modifications he’s had done, as well as why he changed his name when he turned 30. He said his first rituals were performed through mimicry: something resonated with him and he acted it out. But with time, it morphed to become his ritual, imbued with personal meaning.

I’ve unknowingly built my own body modification ritual: every year, I add a new ring to my septum piercing, stretching it over time. At first, the timing was a coincidence, but it has become intentional, a way of physically marking my life.

“People need to go back to ritual,” Landry said. “It makes sense. It’s human.”

Landry’s view of ritual is similar to Matlock’s: ritual is about creating meaning in an unordered world, a way of recharging. And meaning isn’t always literal.

A long-time skeptic, Willow has come around to that idea. He has a neuroscience background, and though he’s approached ritual and meaning-making more from the psychological and physiological perspective than the strictly spiritual, he now sees them as two sides of the same coin: either way, ritual remains a powerful tool — and Willow disclaims that you can enjoy the fantastical without fully believing it. He credits Matlock with bringing him around.

“I’m all about experiencing the ‘woo’ — the ‘woo’ is a lot of fun,” Matlock said. “I love the moments when I look into a forest and go, ‘Ah, I can see a dryad caught in that tree.’ … [But] I think it’s important that people be able to see both sides and live in both worlds, to get a healthy perspective on how they’re practicing and what they’re bringing to this, and what they’re taking away.”

When I came down from my first suspension, the calm followed. It lingered while Pearce and Tamara de-hooked and bandaged me, and stuck with me all the way home. It was no longer the serenity of suspension, but a sense that, underneath everything else, there was a core of calm I could return to. And I did — it was easier to stay calm day-to-day, to recenter myself when thrown off. Over a month after the suspension, the calm remains.

I’m resistant to giving suspension so much credit; like Willow, I’m a skeptic. And yet, things have changed since my suspension.

To take the literalist approach: my suspension broke down the idea I had of my own fragility. My anxieties were less about actual events and more about how I might react — badly, I expected. The new knowledge of my strength, my resilience, is what has created the calm I didn’t know I was missing. This is probably true.

But there is something beautiful about the idea of finding my peace in the calm after the storm, in the silence and stillness of hanging from skin. In being lifted as one being and coming down as another, as something transformed by a brief encounter with serenity.