Othello is currently in a limited engagement on Broadway starring Denzel Washington as the title character and Jake Gyllenhaal as the antagonist, Iago. Tickets are selling from $216 to $921. This caught the attention of Johnny Oleksinski, the entertainment critic for the New York Post, who noted the outsized price in an article aptly titled “Broadway ticket prices are completely out of control — Denzel Washington’s show is charging $900 for just Row M.” After the article was published, the production rescinded his press tickets. The New York Post ended up purchasing their own tickets for Oleksinski. The headline of his follow-up review: “Denzel Washington’s dull Broadway show isn’t worth a $921 ticket.”

Broadway ticket prices have slowly been on the rise, but the precedent for premium ticket costs began with Hamilton. Back during the show’s peak, tickets ranged from $199 to $849. Shows like Othello that boast stunt casting—in other words, casting stars from the world of film—often have a premium ticket price. The Music Man starring Hugh Jackman back in 2021 had tickets priced up to $700. After the wildly successful movie adaptation, Wicked tickets have risen to around $300. The average ticket price for “Good Night and Good Luck,” starring George Clooney, is $315. Costly tickets give rise to an image of Broadway theatre as an entertainment of the super-rich.

Warnings Over Broadway’s Next Act

The rise in prices isn’t just affecting ticket sales. It’s also been making affordable tickets much more expensive for regular patrons. Ticket lotteries such as that run by Broadway Direct, had prices of $15 to $30 20 years ago. Now, they range from $40 to $65. There are other ways to get cheaper tickets, such as going to the box office the day of the performance for rush tickets or TKTS, a place you can visit in Time Square or Lincoln Center for discounted seats. Sometimes these discounted tickets are seats with partial views of the stage or no seats with just standing room, which means you have to stand in the back of the theater for the duration of the performance.

When ticket sales start to get this expensive, it sets the precedent for other shows on Broadway to begin raising their prices as well. This could eventually lead to $300+ tickets becoming the norm, a move that would reinforce an idea of Broadway as “high class” art, which would seem to go against the foundational history of theater as an entertainment for everyone—and its roots as an art form for the “lower class.”

Michael Kantor, a prominent producer, director, and writer known for Broadway: The American Musical, provides a different perspective. “I think Rocco Landesman told me about this in an interview. There was so much scalping going on that they said, look, let’s, let’s just make sure we offer it direct to the person, so there’s no middle man who’s making all the money. People who made the show should make money, and the people who have money can get the best seats.”

High ticket prices aren’t the only cause of concern. Broadway is beset by an array of systemic challenges. Jukebox musicals like Mamma Mia!, where popular music serves as the basis of the score, attract growing audiences. They are inadvertently putting composers and lyricists out of work, by relying on familiarity to sell tickets. Since, in the eyes of producers, it’s less of a financial risk. IP-based shows are similar: they take well-known intellectual properties, such as Harry Potter, Back To The Future and Stranger Things, and adapt them for the stage. Often they have elaborate sets and costumes that are reminiscent of the source material. Biographical musicals use the life, and / or music, of a famous individual to draw crowds. Examples include On Your Feet!, about Gloria Esteban, and MJ: The Musical, about Michael Jackson. If the subject of the show is alive, they will often be involved in the production, as a producer or as a composer. Lately, there has been an oversaturation of these types of musicals and a significant lack of original works. Stunt casting, the practice of casting film celebrities in shows, like in the case of Othello and The Picture of Dorian Gray (which stars Sarah Snook, best known for Succession), is a hot trend as well.

Running costs and budget costs have also skyrocketed. Death Becomes Her has a whopping $30 million budget, with very little going into the pockets of the cast and crew. The majority of the profits goes right back into the pockets of the investors who fronted the $30 million budget. According to the New York Times, producers make on average 3% of the weekly grosses. It’s not just money that performers have to worry about. Parasocial relationships and toxic fandom culture are leaving patrons and cast members alike in unsafe situations. Kit Connor, known for Heartstoppers and Ready Player One, was in a production of Romeo and Juliet this past fall. An excited fan threw a bracelet at Connor to get his attention at the stage door, which resulted in his getting mildly injured. In some cases, actors are made to feel unsafe by people within the industry. Scott Rudin, the disgraced producer accused of abusive behavior, is said to be planning his return to Broadway. This is not just an isolated occurrence. Other abusers within the industry are being given second and third chances even after allegations have gone public.

Government-funded theater is slowly disappearing. Donald Trump has been appointed the head of the Kennedy Center and reconstituted the board by asking the former board members to resign. Trump then replaced them with people who support him and share his sentiments about art. Performances at the Kennedy Center, including such shows as Hamilton and Legally Blonde, were cancelled. Cancellations at the Kennedy Center in turn affect the stream of shows that head to Broadway, since the Kennedy Center acts as a proving ground for new material.

Finally, despite efforts to eradicate it, racism persists in the industry. With these many challenges, are we entering a dark age of the theatrical industry?

The Legacy of Racism

While things have improved from a time when harmful stereotypes and blatant racism were the norm, there is much work to be done. There was a significant call for change within theater during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, which spurred the creation of the Black Theater Coalition, an initiative to protect black artists in theater. Outside of this initiative, very little has been done when it comes to protecting artists of color.

Even before the George Floyd murder and BLM fixed new attention on Broadway’s race problem—and #oscarssowhite spawned online discussions of #broadwaysowhite—the industry had been working to solve some persistent problems. Among the endemic issues were white actors playing roles of people of color, white voices dominating the creative process, and the price of tickets, which kept people of color out of theaters. But concern isn’t the same as solution. Years after this conversation began, not enough has been done when it comes to cultivating a safe space for people of color in theatrical spaces.

Actors are often typecast in roles, and this especially applies to POC actors. The environment has evolved so that certain people are only considered for certain stereotypical roles, like Asian actresses being told they would be the perfect Kim in Miss Saigon. It’s something I personally have to think about, as a latina actress.

I entered my Musical Theater History II lecture near the end of the semester last fall at NYU. It was a designated discussion day. The chairs were placed in a haphazard circle. Barrie Gelles, my professor and a theater historian, urged us to talk about our opinions on the current state of the theatrical industry in a class of 20. Students rambled and ranted about their Wicked movie takes and how movie musicals kinda suck or how Broadway is becoming too “politically correct” and only churning out safe “neoliberal think pieces.” Once the conversation began to fade, I raised my hand and simply said, “Broadway has and is continually mistreating POC and minority performers.” That comment evolved into a difficult conversation on where to draw the line when it comes to inclusive casting, with many students feeling conflicted with my stance. Out of everyone in that classroom, there were only two minority students, including myself.

I have had to constantly grapple with the fact I might never play roles that should be portrayed by a Latina performer. Eva Perón in Evita and Maria in West Side Story were originally played by white women on Broadway. Ethnic and race-conscious casting weren’t the norm until the 2010s, but even then, things slipped through the cracks. Jessica Vosk, a Broadway veteran, played Anita in a concert version of West Side Story in 2014. She donned a stereotypical Spanish accent and sang “A Boy Like That,” portraying a caricature of a “spicy latina” instead of the strong-willed and witty Anita we know and love. I’m hopeful that things will change, but for now, I’ll have to bite back my disdain anytime I see an all-white regional production of In the Heights.

Bad Manners

At the end of 2023, I won a ticket lottery for Spamalot, a musical based off of the film Monty Python and The Holy Grail. This production initially was performed at the Kennedy Center in DC, then transferred to the St. James Theater on Broadway. It ran from November 16th, 2023 until April 7th, 2024. The theater was bustling with energy, yet there were plenty of empty seats in the balcony where fellow lottery winners and low-cost ticket holders sat with me. I had an extra ticket and had invited my friend Cole, a big fan. We made our way to our seats and were excitedly taking photos of the stage and flipping through our Playbills. There was a pair of women sitting right behind us who also seemed excited to watch the show. As soon as it started though, things turned sour.

The balcony in the St. James theater is steep, so to see pretty much anything onstage, you have to lean forward slightly. Cole, who is over six feet tall, had to lean forward like everyone else. The women behind us began to snap at him mid-show, saying they couldn’t see anything. The pair complained until intermission, when Cole decided to talk to an usher. He came back with two booster seats only to find the pair gone.

Altercations like these are not uncommon. Frustrated patrons who get into fights with other guests, actors stopping shows to chastise audience members, and ushers having to escort people out of the theater. There has been a decline in theater civility since theaters reopened from the pandemic in 2021. On April 25th, 2025, A man was punched by another patron during Gypsy and had to be moved to a new seat. The show still continued. The internal flaws of the theatrical industry are bubbling up to the surface, but does anyone want to fix it?

Social media may be making things worse. There are some positives to this: theater fans all over the world are able to connect with one another and post about their favorite shows. The shows are getting free promotion and people are able to form a community with like-minded individuals. Yet, there seems to be an undercurrent of toxic fandom behavior. On March 16th, user “it’s-greased-lightnin” posted on the unofficial The Outsiders musical Reddit page. The post describes the various actions of multiple people within the fandom. It alleged that fans of the show began to bully and harass cast members of the show in person and online. They have been attending shows with the sole purpose to flirt with the actors backstage. There were screenshots of fans calling multiple actors slurs. In one notable screenshot, multiple fans have admitted to stalking several of the leads. The worst of it: One fan threatened to bomb a cast member’s home. The cast got wind of these messages and alleged behavior. A member of the cast, Melody Rose, had to address the situation on an Instagram live stating “We will find out who you are, and tell the theater for you not to come back.”

This isn’t the only incident of inappropriate fan behavior. A young girl who went by “Bikini Bottom Savior” online began to stalk members of Spongebob: The Musical cast, hiring Ubers to follow various cast members to their homes. Multiple Broadway performers and celebrities, such as Barett Wilbur Weed and Brendan Urie, have had to stop stage-dooring, the act of waiting at the stage door to meet the performers in the show, due to feeling unsafe around fans. This type of intense behavior can be linked back to parasocialism. Fans now feel entitled to interact with their “favs” time just because they bought a ticket, even if it means following them or threatening them if they don’t.

Theater has always had a sort of tumultuous history. Rowdiness and audience interjections were common in the past, like during the age of Elizabethan theater where it was common for people to throw rotten food at performers to show their disapproval of the performance or the show or the play. The passion of patrons can turn into fights and riots. The Astor Place Riot was a melee and massacre that took place outside of the Astor Place Opera House, just off Broadway at Eighth Street on May 10th, 1849. Its cause was a long-running dispute between Edwin Forest, an American actor, and William Charles Macready, a well-known British actor, over who was better at performing Shakespere. Working-class patrons preferred the American, while the upper crust, in the best seats, preferred the Brit. The dispute spilled from the theatre onto the street, where it resulted in the death of 31 people.

A couple of centuries later, on April 26th, 1865, the best-known act of political violence inside an American theater took place when Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at the Ford theater by actor John Wilkes Booth.

Art is inherently political. It is a powerful tool that can be used to raise awareness about our world, the human condition, and as a form of protest. In his book, Michael Kantor cites E.Y. “Yip” Hamburg, a lyricist, who shares this very sentiment. “Songs are the pulse of a nation’s heart. A fever chart of its health. Are we at peace? Are we in trouble? Are we floundering? Do we feel beautiful? Do we feel ugly?…Listen to our songs.”

A modern day version of this passion-turned-sour exists in the story of a Black box office worker who was called the n-word by a patron at Little Shop of Horrors in November 2024. The cast then reprimanded the patron for his behavior. Yet, these actions aren’t only committed by patrons — artists and creatives may also be partly to blame. Patti LuPone was accused of racism by Kecia Lewis for saying Hell’s Kitchen, a show with a majority black cast, was too loud. Lea Michelle, who was just in the recent revival of Funny Girl, was accused of racist behavior from various actors who worked with her in the past. Even threatening to defecate in Samatha Ware’s wig while on the set for Glee. Not to mention the countless producers, actors, and directors, like Ben Vereen and Amar Ramaser, who were accused of sexual misconduct. Have we really lost the plot when it comes to mutual respect in artistic spaces, or has theater always sought out to get an emotional rise out of artists and patrons alike?

David Alpert, a Broadway director, sees there’s been a noticeable change with uplifting people of color performers. “ I’ve lived in New York almost 20 years, every ensemble was very white. Now, when I see shows, there is a change. A change that, in the grand scheme of history, that’s a blink of an eye.” Alpert has also seen great improvements in other aspects when it comes to representation. “I’ve seen people win Tony Awards for performance, who are non-binary, who use a wheelchair, who, you know, speak openly about gender identity and religion. I’m like, holy crap. That is so different than when I was a kid watching the Tony Awards.”

Turmoil Upstream

Government-funded arts on the state and national level have been used to cultivate cultural enrichment or promote the ideals of the United States. One of the most famous examples of government-funded theater is The Kennedy Center. Founded in 1958 by John F. Kennedy, the arts center opened in 1971 and was made a living memorial for JFK after his assassination. The inaugural performance was Leonard Bernstein’s Mass: A Theatrical Piece For Singers, Players and Dancers. Lately, The Kennedy Center is mainly in the news for President Donald J. Trump appointing himself as the Board Chair to avoid putting on “totally woke” shows. Dozens of theatrical productions and performances have since been cancelled, ranging from touring shows to original performances such as Eurika Day and Shear Madness, which is creating holes in their programming.

Yasmin Willians, a musician and composer, reached out to Richard Grenell, the interim executive director, regarding the number of cancelled performances and rollback on DEI initiatives. She then posted their conversation on Instagram. Williams asked in an email: “Does the President actually care about artists cancelling shows at the Kennedy Center? What, if anything, has changed about the Kennedy Center regarding hiring practices, performance booking, and staffing?” This sparked a heated back and forth with Grenell making assumptions about William’s politics, referring to “cutting the DEI bullshit” due to a lack of funding, and accusing Williams of calling Grenell intolerant.

He finished by saying “Let me remind, YOU reached out to me unsolicited and accused me of being intolerant. Don’t be a victim now. You asked.” She then responded “Thank you for your responses! I would request you re-read my original email since you seem to be extremely defensive and rude for no reason. I never accused you of being intolerant…I don’t know you.” She concludes her email, saying that she was simply asking questions regarding what other people have said about the Kennedy Center. “I’m honestly shocked at how unprofessional your emails are,” Williams said, “but I guess that’s the par for the course these days, on both sides of the political aisle.”

I visited the Kennedy Center at the end of March, and was able to talk to a volunteer tour guide, Ritch, a proud member of the Kennedy Center for 15 years and a tour guide for eight. As he was going through his script stating fun facts about the gifted art found in the center, we stopped at the terrace looking into a permanent exhibit based on JFK’s contributions to the arts. He highly recommended I visit the exhibit after the tour was complete. So, after touring The Opera House and Eisenhower Theater, I went back up to the terrace to explore.

I began looking through old posters and production photos when a clip of JFK began to play on the speakers. The speech was related to raising money for a New National Culture center, which would become the Kennedy Center. A man nearby began to scream “Viva Trump” over and over until the recording stopped playing. He left in a rush mumbling about how the “woke agenda” is corrupting the arts. The staff and guests remained silent until the man left. Then everyone went back to what they were doing. That moment felt like the perfect encapsulation of what’s happening at the Kennedy Center: A sudden cataclysmic outburst that leads to everyone being left to continue on as normal, or as close to normal they can despite it all.

Beyond Broadway

Off-Broadway shows follow a similar financial structure to Broadway and touring shows, but are on a slightly lower pay-scale and budget depending on the size of the cast and the theater. There’s always exceptions, especially for celebrities or big names. They also could have a mix of equity and non-equity contracts depending on the show and theater. Regional theaters are professional theaters that can be found across the United States. They are for-profit, and often have a mix of equity and non-equity contracts for artists. Touring houses are theaters that host National Tours. Non-commercial shows that are solely funded by institutions, like the government, nonprofit theaters, or schools. Some non commercial shows can be found at non-profit theaters like Lincoln Center, Manhattan Theater Club, Vineyard Theater, Playwrights Horizons, and New York Theater Workshop. This also includes high school theater, university theater, and community theater.

David Herskovits is the artistic director of Target Margin Theater, a nonprofit theater based in Brooklyn. When it comes to funding, he believes all theaters have been struggling. “Globally, to me, it’s clear that the industry has struggled in the wake of the pandemic. Generally, has struggled and been slow to recover its audiences and therefore its financial support in various forms.” In his eyes, commercial theater is getting to a better place now, but the same cannot be said for nonprofit theaters. There was a lot of aid given during the height of COVID-19, but when it was pulled, many theaters began to suffer. “So there was a kind of sugar high, of pandemic special money. And by the time 2022 rolled around, you know that was really over. It was a shock, I think, to a lot of companies.”

Theater has a global market as well, notably the West End, London’s theater district akin to Broadway. The West End spans over a larger area that’s located in central London with theaters bordering Westminster City Council, Soho, Mayfair, Fitzrovia, and Marylebone. There are 31 theaters that are considered to be a part of the West End. Notably, a lot of productions have had their start on the West End, then bring the show from overseas to Broadway in a transfer. Composer Lord Andrew Lloyd Webber notably started the “British Invasion of Broadway” back in the 70s with shows like Jesus Christ Superstar, Evita, and The Phantom of the Opera.

One of these West End transfers that’s currently running on Broadway is Jamie Lloyd’s Sunset BLVD, a reimagined production of Lord Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Sunset Boulevard, which is based on the 1950 film. Tightly packed in the mezzanine, I sat with my friend Johnathan Lewis, also known online as “The Sweaty Oracle,” a bombastic character who spills Broadway “tea.” Outside of the persona, he is quieter and much more relaxed, but still holds strong opinions about art just like his character. Earlier in the day, he urged me to go with him to see Sunset BLVD, so I agreed.

The show abruptly started just after 8:10 with a large swell of music from the orchestra. Norma Desmond, the eccentric washed-up silent film actress played by Nicole Scherzinger, danced hypnotically to the overture, moving around the stage as if in a daze. She slowly made her way to the back of the hazy, harshly lit set and sat facing away from the audience. That’s when Joe Gillis, a frustrated Hollywood screenwriter played by Tom Francis, emerged from a body bag placed center stage. Overwhelmed by the brilliant orchestrations, choreography, lighting, and acting; I began to weep. I kept thinking to myself as the show continued that we need more productions like this.

Follow the Money

Ticket costs have skyrocketed and running costs have followed. But where is the money going? If we’re talking about commercialized productions, which includes any show on Broadway and Equity National Tours, their main goal is to make profit by getting investors and producers to financially back the performance. They follow an Equity production contract, which guarantees all performers are in the union and receive at the minimum $2,200 per week, according to the Actors Equity Association. They must also receive other benefits like health insurance and paid time off.

The running cost for a show is the amount of money it needs to earn weekly to survive. This includes paying performers, musicians, crew, the creative team, the theater hosting the show, and the producers and investors. The running cost greatly depends on the show and theater. For example, Hamilton has a weekly running cost of around $650,000, while Wicked has a running cost of over $1 million dollars. But, a big chunk of that money goes to producers, investors, people who own creative rights, and the theaters. The performers, musicians, and crew often get the smallest share.

In the case of Hamilton, the original budget was $12.5 million. On top of the weekly running costs, there’s other productions occurring. They are two national touring productions, a West end show, UK/Ireland tour, and an Australian production. With all those productions running, the creators and producers have made hundreds of millions of dollars since 2016. The producers of Hamilton make on average $52,000 weekly just from the Broadway production, since they get 3% of the grosses each. 42% of the profits go back to the original investors. While the performers make on average $126,000 annually.

It’s not just ticket sales, merchandise also makes productions a large sum of money. Tee shirts, hoodies, cups, even stuffed animals and books generate money for the production. Popular long running shows, such as Hamilton, The Lion King, and Wicked have done elaborate collaborations with clothing brands. Not to mention the physical release of cast albums and streaming royalties generate profit for the production as a whole, but very little of that money is set aside for anyone but the producers and creators of the show.

While producers and investors can make a lot of money from financially successful hits, they can also lose a great deal of money from flops. Spiderman: Turn Off The Dark had a budget of around $75 million and lost over $60 million after running for three years. It was considered the most expensive musical of all time. Carrie famously ran for 16 previews and five performances losing $8 million in the process. Notably from the 2024-2025 season, Swept Away grossed around $ 4.5 million, ending their run with a loss of $10 million.

Big Bets on Proven Material

When a show is created, producers and investors want to ensure that it will be profitable. In their eyes recognizable properties, like movies, TV shows, or books are the most reliable sources of profit. Biography musicals, jukebox musicals, and stunt casting are the easiest ways to succeed, but in some cases these practices have been shown to work only in the short run.. The longest running musicals seem to infuse familiarity with new ideas. Hamilton, for example, takes the life of a historical figure and recontextualizes it by implementing people of color performers and making it a rap musical. Wicked takes inspiration from a Gregory Magurie novel, but takes the story in a completely different direction. So, does this mean patrons only want to see adapted works?

People within the industry say no. Rona Siddiqui, a composer and lyricist who worked on the Tony Winning musical A Strange Loop as the music director, would like to see more producers take a chance on original stories. “I give so much credit to Barbara Whitman, the producer, because not only is she the one who picked it up in the first place when nobody else would touch it, she then is savvy enough to see how audiences are responding to it, which was like people were voraciously hungry for that kind of honesty and depth. And that’s what I’m talking about. Like people want it. They want to be challenged in that way. So she saw the audience’s response, and she fought. She fought. She got us to DC, and she wouldn’t let it end. She just was in conversation with those theater owners, like, non stop until we got a space and we got to move. And she made that happen. It’s her tenacity. We need, just like way more of her.”

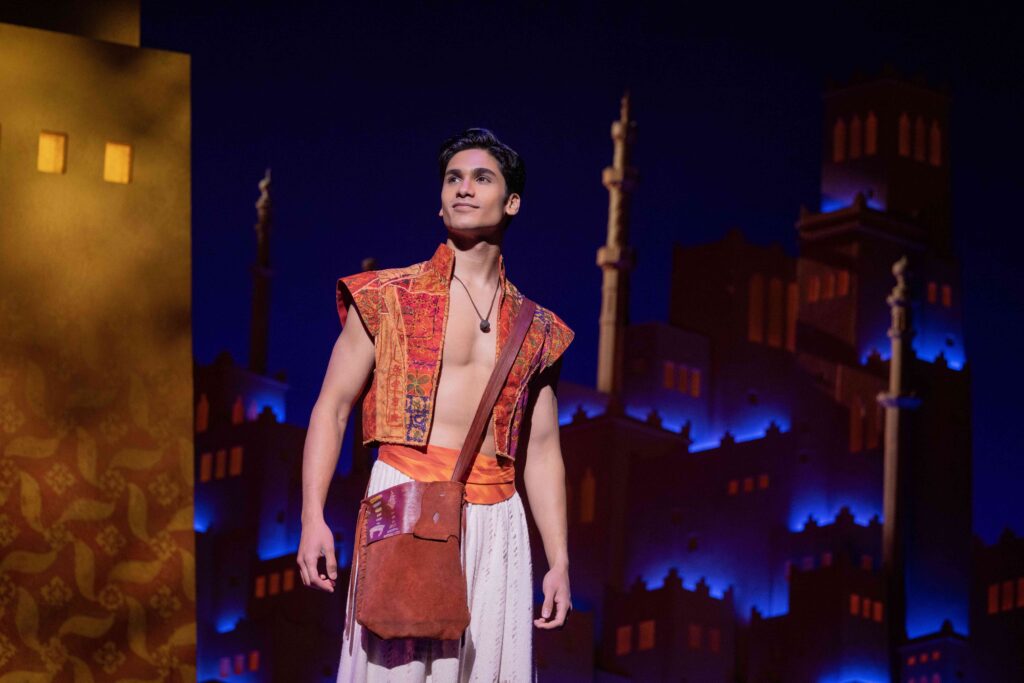

Fans of theater are mixed. Some people on TikTok, Reddit, and Instagram yearn for more original works, while others are obsessed with Heathers, Beetlejuice, and Mamma Mia! But how does this affect the average tourist who might not know much about Broadway? According to the weekly grosses, it depends as well. Big Disney properties, like Aladdin and The Lion King consistently do well in the box office and are well liked by audiences. Yet the biography musical A Beautiful Noise closed with inconsistent box office numbers, with some weeks selling well and others causing the production to lose money. After all, 71% of tickets sold for Broadway are sold to tourists.

Danny Decker, an aspiring composer and lyricist, as well as an acquaintance of mine, wants one thing: his original work to flourish; for his show, House of Eerie Figures, a story following two brothers who bond over their interactions with ghosts, to have its world premiere. To gain producers or grants to fund his original work so he can finally show their work onstage for the first time as a composer. Then, Decker will finally make money off of the musical he has spent years creating. And then, the show will take off and evolve into a Broadway hit. Decker has a limited amount of time to devote to his artistic endeavors, working as a Marketing Manager for George Street Playhouse to be able to afford living in NYC, while staying close to the industry he loves. In the beginning, the show’s budget is tight. Whether it be industry readings or recording an album, everything comes from Decker’s own pocket. Balancing the cost of living in New York City and his passion project is a difficult task, and if no one goes to see Decker’s show, his hard work will have been for nothing.

Into the Digital Age

Though the warning signs are there, some members of the theatrical industry and theater fans believe that Broadway is doing just fine. They choose to see rampant closing notices as a normal occurrence. They are overly supportive of new shows, even if they might not be very good; they buy tickets costing over $200 just so they can see whoever is the B- celebrity they manage to cast. They obsess over actors and create parasocial relationships with them, feeling entitled to their time at the stage door even if it makes the actors uncomfortable. Broadway, I often feel, is imploding; I’m screaming and the people who need to hear it are covering their ears. They pride themselves on understanding the subtext of Cabaret, when in reality they’re Sally Bowles; willfully ignorant to the world around them…after all, money, in fact, does make the world go ‘round.

Despite theatre in New York being older than the Republic, the behemoth of an industry has had to constantly evolve to keep up with the changing media landscape. Its latest development? The Proshot, an abbreviated term for “professionally shot” that refers to live shows, notably live theater being recorded for viewing by an audience later. Many shows have had proshots recorded, but why haven’t more of them been released to the public?

There are traditionally four kinds of proshots that are taken at Broadway shows. The first kind is a multi-camera production aimed to be sold to a streaming service, like Netflix or Apple TV. Hamilton, Come From Away, and Diana have been shot in this way, and among the places they can be viewed is BroadwayHD, a streaming service dedicated to providing high quality proshots of plays and musicals. These types of proshots are behind a paywall.

The second type of proshots are captures done by Theater on Film and Tape Archive at The New York Public Library. They are usually two- to three-camera shoots during a singular performance. These recordings are not meant to be distributed, but are free to watch for library members who agree to submit to a rigorous application process. This archive also does not film every show on Broadway; anything before 1970 was not filmed by the NYPL.

The third type of proshot is B-roll footage for publicity and commercial purposes. These shoots are elaborate, and it can take a full day to capture all the desired footage needed. These types of proshots do not film the entire production, but it is easy to gain access to this footage for free, such as the B-roll of the original production of Ragtime.

The final type of proshot is archival footage. Similar to Theater on Film and Tape Archive proshots, these are basic. They are often filmed with one camera on a tripod from the back of the house. It’s not meant for commercial purposes and is often incredibly difficult to access, such as the booth footage from Carrie.

Proshots make theater accessible, yet they offer a new perspective due to the change in medium. “When you’re watching a proshot, it creates a new atmosphere you wouldn’t normally experience in a live performance,” Decker said. “The proshot is one performance frozen in time, so you experience how the performers were feeling that specific day.” While you might not be physically in the theater, viewers are still affected and entranced by that recorded performance.

Proshots, while an incredible innovation, have their faults. Only a limited number of productions have them, and even fewer of these are ultimately accessible to the public. Some get stuck in negotiation hell, trying to be sold to a streaming service, but to no avail. Even the proshots that have been released to the public are often hidden behind paywalls or are hard to access. With all of these ways of preserving theater, what if there was an illegal way to capture a show? Enter the world of so-called “slime tutorials.”

Slime tutorials has become a slang term for illegal bootleg recordings of theatrical productions. The term came about as a way to evade detection algorithms from taking down the illegally recorded content. For example, if you’re looking for a Heathers bootleg, you’ll find “A Teenager’s Guide to Love and Murder HD slime tutorial” instead. On platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Tumblr, slime tutorials reign supreme, creating a mess for theater artists and creators.

On one hand, Equity rules state that recording of any production of any kind is strictly prohibited. Recording a theatrical production illegally and distributing it is considered copyright infringement. It is incredibly distracting to performers when you record a production. Due to the powerful stage lights and the reflective lenses on phone and video cameras, when you are onstage, you can see them easily. It is also taking away money from the artists, technicians, and production team. If you can see a Broadway show for free online, most people would rather do than spend hundreds of dollars to see it in-person.

On the other hand, slime tutorials are accessible to those who can’t afford to fly to New York to see Hadestown. Instead, they can look up “Hades Slime Tutorial 2.0” on YouTube and watch the entire show for free. Slime tutorials also help keep the theater fandom alive, because they allow fans to share their favorite musical moments or introduce others to new shows they otherwise wouldn’t find out about. Ironically, slime tutorials can also act as marketing for superfans. A shared recording, legal or illegal, of Aaron Tveit in Moulin Rouge singing an opt-up on “El Tango De Roxanne,” can cause more people to want to hear him sing it live.

The Movie Musical

Film and stage productions are very different mediums, yet both have the same end goal: to entertain audiences. Films are more subtle and depend on editing and cinematography to get the desired effect. They also are created in multiple takes, meaning that it could take hours filming one scene to get each desired angle and delivery by the actors. Stage, on the other hand, is “live,” with each performance slightly different from the last. Stage shows are meant to be ever-changing and adapting, so what happens when you take a traditionally live artform and adapt it for film? Thus, the movie musical was born.

During the Golden Age of Hollywood from the 40s and 50s, movie musicals reigned supreme, so much so that they were often adapted into stage musicals. For example, White Christmas was a movie musical first before it became a Broadway musical in 2014. The world of theater became even more complicated with the upside sense of a modern movie musical. Now, we live in the era where the cycle has flipped: stage musicals are becoming movies. From the massive failure of Mean Girls and West Side Story (2021) to the monumental release of the Wicked movie, it has been proven to the public that musicals can be adapted to film and be good, but why have so many recent attempts failed?

Public perception of musicals has gone through phases. Media like Glee and High School Musical were first praised, but as time went on, they were seen as cringeworthy. While both were successful properties, they also played into stereotypes that portrayed theater kids as obnoxious. Plus “traditional” musical songs aren’t reflective of the music of the modern generation, which can also be seen as outdated.

With failures such as West Side Story (2021) and Mean Girls (2024), their marketing was working against the production. Mean Girls did not market itself as an adaptation of the Broadway musical from 2017, which led many people to believe it was a remake of the original movie. West Side Story (2021) was plagued with controversial casting, production delays, and departed from the original source material, which caused people to lose interest or forget the movie was even being released.

Wicked was smart: It remained faithful to the original version of the show, but added extra context for world-building and character development. It casted two famous celebrities, Ariana Grande and Cythia Erivo, who both have performed on Broadway previously. It also poured billions of dollars into marketing, commercials, and brand collaborations; which continued to stir excitement from non-theater and theater fans alike. Plus, now people can see the musical without paying hundreds of dollars.

The success of Wicked suggests that theater’s transition to the film world will continue. “Musicals have the potential to be blockbusters because they typically can bring in a large number of families,” stated Kevin Goetz, founder and chief executive of Screen Engine/ASI, a market research and analytical firm. If musicals continue to rack up millions, live performances will continue to have proshots and be adapted into movie musicals. Individuals will also continue to create slime tutorials of their favorite shows. The cycle will continue and evolve. More movie musicals will be greenlit due to the immediate success of Wicked. More proshots will be released due to the success of Hamilton on Disney+. Slime tutorials will start to become wide scale projects between multiple people and cameras. Theater’s transition to the digital sphere was inevitable, hopefully it will continue to generate an interest in the live versions of these productions and help rejuvenate the industry.

The Need for the New

Tourists, fans, and artists alike yearn for deeper stories, ones with substance that speak to more people. This season, we have Real Women Who Have Curves, Buena Vista Social Club, and Maybe Happy Ending: shows that have excellent representation that tell important and relevant stories. While Real Women Who Have Curves is based on the 2002 film, but tells a different story about being an immigrant in the 80s having to hide from ICE and learning to love your body. Buena Vista Social Club follows members of the real life band spanning from the 1950s through the 1980s. The show is completely in Spanish and follows the band through the rise of Fidel Castro and the road to creating their debut album Buena Vista Social Club. Maybe Happy Ending follows two robots in South Korea that find love.

We need more fresh-faced composers who are eager and passionate. Composers like Rona and Danny, who are passionate about their craft. Directors like David Alpert and David Herskovits who strive for social change and foster a welcoming environment in the rehearsal room. Producers like Barbara Whitman who care about underrepresented voices. Theaters like Papermill Playhouse with administration like Jen Bender who are willing to take a chance on new musicals. People who are willing to strive to make a difference in this industry for the better.

In Michael Kantor’s Broadway, Gilbert Gabriel states, “Every race in every age has picked out some one street, one square, one Acropolis mount or Waterloo Bridge to celebrate … Let it be known to the Americanologist of 3000 A.D. that we idolized a strange, boomerang-shaped, nightly fiery thoroughfare of broken hearts and blessed events, which we called Broadway. That will explain us.”

I recently had an audition appointment for a role in a developmental reading of a new musical at The Public Theater. The show is shooting to go to Broadway, ideally within a year or two. I walked into the rehearsal space a little lost. After all, it was my first time in the area. While I was waiting for my appointment, Real Women Have Curves was rehearsing. They were on break, but you could tell they were a tight-knit cast laughing together and gossiping, like a family. I went into my audition with that same amount of confidence and joy.

The audition went well, so I immediately called my manager. I told her it went well, and Peggy wanted to know each and every little detail. I told her how they seemed to be impressed with my preparedness and my connection to the material and the music. She just kept saying “your time will come” over and over again. And if that turns out to be true, I hope to be an artist who pushes for change — not for superficial reasons, but because I really love this industry. I want people who find the same joy I get when I see a show or perform in one. All I can do now is hope that people will listen and be willing to let change happen.