A comic convention can either be paradise or the seventh circle of hell.

For many, they offer chances to meet like-minded people, hear exciting announcements, buy rare comic books, and meet big-name writers and artists. For others, it’s a reminder that not everyone is welcome in this space.

In 2014, comics reviewer Rachel Knight attended Special Edition NYC — a comic convention — at the Javits Center with her friends. The group went dressed as the all-women superhero team The Birds of Prey, specifically as written by acclaimed writer, and vocal advocate for gender diversity in comics, Gail Simone.

Simone was actually attending the convention, and Knight and her friends wanted to make sure to meet her while dressed as the characters she wrote about. So, they got in line like everyone else. Simone spotted them, and got so excited.

“She saw us, she pulled us out of the line to take photos with her, and it was really nice,” Knight recalled. “She was lovely. It was maybe five minutes, we didn’t hold up the line, like, permanently.”

This made some attendees angry — they had been waiting in line longer, why did these people get to cut? But rather than staying angry about that, some male fans started accusing them of not even reading the book that inspired their cosplays (costumes, often homemade, worn to events like ComicCon).

Cosplays are expensive — they take money, time and resources. To commit to creating something like one, you need to commit, and you need to have passion.

“You spend 150 hours making the most articulated costume possible, and then somebody’s like, ‘Well, she probably hasn’t even read the comic books,’” Knight said. “Who does this? Who spends this much money? ‘Cause, like, the attention is not that much.”

The comics industry has a gender disparity, to say the least. Female writers and artists say they are not given the time of day, female characters are constantly sexualized, female fans are demeaned for loving what they love, and female-led books get canceled.

This gender disparity is exacerbated by a long history of female stories being diluted to tropes or objectification, as well as the impacts of how the comics industry as a whole is structured.

A wondrously wacky beginning

Many consider Wonder Woman to be the first female superhero. Though she actually was not, she could be classified as the first impactful woman superhero, and certainly among the most recognizable.

Created by psychologist Dr. William Moulton Marston in 1941, Wonder Woman was at least partially inspired by his wife, Elizabeth Holloway, and the couple’s life-partner Olive Byrne. The specifics of the three’s relationship with one another can be murky, but Marston seemed to love both women as his wives, and the three lived together.

“Having a female character that prominent and that well-renowned that early on was a big thing,” said longtime comics fan Carol Anne Brennaman of the X account @AnneComics, which has over 25,000 followers, and The Comics Collective Podcast. “I think a lot of people forget looking back just how controversial Wonder Woman was.”

Despite being an icon for young girls to look up to, and the first notable woman superhero, Wonder Woman was not immune to the sexualization female characters have faced over the decades, as will be seen. Most Wonder Woman stories found the hero bound by chains and needing to escape — imagery which can appear sexual to many.

The constant use of bondage in Wonder Woman stories led to a letter to Marston from then-president of All-American Comics (which would become DC Comics) M.C. Gaines, wherein Gaines asked Marston to limit chain bondage.

“Miss Roubicek [Gaines’ assistant editor] hastily dashed off this morning the enclosed list of methods which can be used to keep women confined or enclosed without the use of chains,” the letter reads. “Each one of these can be varied in many ways — enabling us, as I told you in our conversation last week, to cut down the use of chains by at least 50 to 75% without at all interfering with the excitement of the story or the sales of the book.” (According to Les Daniels in “Wonder Woman: The Complete History,” the list itself is lost to time.)

Wonder Woman endured, and as bondage became less integral to her character, she became the icon we know her as today.

“Somehow we got the most empowering female figure that you can ever imagine, out of a book that used to be a fetish book — that used to be, ‘Oh, we’re gonna tie her up in every single issue,’” said comics influencer @ThePandaRedd, who has more than 1 million followers on TikTok.

Beyond that, though, Brennaman explained that Wonder Woman has almost become a representation of how executives, writers and readers all view female superheroes.

“Ever since her creation, it’s been interesting to see the ways that people try to force Wonder Woman to fit their narrative rather than to make a narrative that fits Wonder Woman,” Brennaman said. “Her existence and her treatment throughout the years has been a great barometer for how the industry views its female characters.”

Since then, that view has been muddled by tropes, fallbacks, and continued sexualization.

A chilling fate

The death of Gwen Stacy in a 1973 Spider-Man story is a pivotal moment in the history of women in comics. In the story, Peter Parker (Spider-Man) had a girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, who was killed when the villain Green Goblin dropped her off the Brooklyn Bridge. He killed her not because of anything Gwen did herself, but to hurt Spider-Man and provoke him to fight.

Though it predated the term by several years, Gwen Stacy’s death is an example of “fridging” — a term coined by Simone in 1999.

Fridging refers to when a female character is killed, injured, or otherwise tortured for the sake of advancing a male character’s story. The fridge name comes from a prime example of the media trend, wherein the girlfriend of Kyle Rayner’s Green Lantern, Alexandra DeWitt, is found dead, stuffed in the hero’s refrigerator, in a gruesome “call to action” for the male hero.

“I can’t quite shake the feeling that male characters tend to die differently than female ones,” Simone wrote on the website explaining the trend. “The male characters seem to die nobly, as heroes, most often, whereas it’s not uncommon, as in [female DC villain] Katma Tui’s case, for a male character to just come home and find her butchered in the kitchen. There are exceptions for both sexes, of course, but shock value seems to be a major motivator in the superchick deaths more often than not.”

Simone received a lot of backlash for her observations on this all-too-common trend, which she put out on her website, seemingly to encourage conversation.

“Tragic things happen to everyone; in fiction this is called drama,” wrote a respondent named Scott in an email that Simone posted. “If you can’t deal with it, maybe you shouldn’t be reading at all. Watch sitcoms or MTV. Seriously, am I the only one who thinks your views are just feminist paranoia? Now *that’s* disturbing.”

The issue many have with fridging is not necessarily in the fact that a bad thing happened. It’s that the bad thing happening is what defines the existence of a character from an underrepresented group, and that the purpose of that bad thing is to boost the story of a character from a well-represented group.

“Fridging almost universally means that the writer thinks that you will see this character as an object for the story,” @ThePandaRedd said. “They’re gambling on you … not really [empathizing] with them as a person, but empathizing with the person who’s going to be affected by it.”

A token effort

Another common trope found in those rare instances of women being represented in comics is “the token woman,” or the sole woman on a team. This legitimizes an otherwise male-centric story, as — technically — there is a woman there too.

Often, this woman will be used as a love interest exclusively, or as eye-candy for the male gaze, other times it is an earnest attempt to give some representation, but it falls flat because of one character not being able to speak for half of the world’s population.

I know from personal experience that the constant utilization of the token woman in superhero stories can actually have the opposite of its seemingly intended effect.

Before I was 12, I had never seen a Marvel movie. My parents and brother, though, were huge fans. They dragged me to the movie theater to see “Avengers: Age of Ultron,” and I did not like it at all — so much so that I did not watch another Marvel movie for three years.

“Avengers: Age of Ultron” is notorious for its arguably misogynistic portrayal of women in certain areas — a feat in itself given there are only about five women in the movie total, and only one who is actually a superhero for the full movie (The Black Widow — Natasha Romanoff, portrayed by Scarlett Johansson). In the movie, this sole female superhero winds up lying on her back with a man’s head resting directly on top of her chest, acts as a romantic interest in a relationship with the Hulk that has zero story precedent and almost zero follow through, and is the only member of her team captured by the villain.

Arguably most noteworthy, though, is her character arc’s focus on motherhood. Fans learn in “Age of Ultron” that Natasha is infertile due to a forced procedure when she was a child. She even divulges that being unable to give birth makes her feel as though she is a “monster” — comparing herself to The Hulk.

This is a story that some audiences can relate to, and not every story needs to be relatable to everyone. But, if Natasha’s arc is about the trauma inflicted upon her as a child, and does not go beyond that, it will likely be hard for viewers — especially young viewers — to relate. This would be fine, if it weren’t for the sheer lack of other options the female audience has.

Not many male viewers can relate to being a genius billionaire like Iron Man, or a Norse God like Thor, or any of the other male characters. But they have options, all of whom are given backstories with some level of relatability. The genius billionaire experiences panic attacks, the Norse God struggles quietly with his own self worth and purpose. Not everyone will relate to everything, but with five options in the main six characters alone, there’s bound to be something for viewers to relate to.

Meanwhile, female viewers have one option on that main team — Natasha — leaving audience members like myself scrounging for scraps in the four other women with speaking roles, none of whom have backstories that are deeply explored. The closest we get is Wanda Maximoff (The Scarlet Witch, played by Elizabeth Olsen), but she is a villain for most of the movie, and her redemption arc is not really given much attention when it does happen.

I remember leaving feeling like I was not meant to watch this movie. There was no one for me, nothing for me to really jump onto and love. Though the lackluster portrayal of women was not the only reason I hated this film the first time I watched, it really stuck with me.

Luckily, this is one area that is seeing gradual improvement behind the scenes. 2019’s “Captain Marvel” was a huge step forward, featuring a powerful female lead and supporting characters, with no romantic story at all.

“I am not anti-love or romance by any means, but women have been reduced to mattering only as mothers and love interests for so long that to simply have that be absent is like so progressive as to be transgressive,” said comic writer Kelly Sue DeConnick, who also worked on the “Captain Marvel” movie and its sequel. “You just never fucking see it ever.”

This sequel, “The Marvels,” released at the end of 2023, was directed by a woman and featured a majority-female cast. The only piece of romance in the plot was treated as a joke, only made fun of throughout the story. And, almost every scene passed the Bechdel Test — as in, it featured at least two named female characters having a conversation about something besides a man.

Still, both movies — particularly “The Marvels” — saw major backlash from audiences, particularly those complaining that it was a “woke” film, thanks to its showcasing of female voices. DeConnick said that some of these critics imply that the people who made the movie did not know what they were doing, and did not understand the comics.

“‘This was made by someone who’s never read a comic,’” DeConnick mocked, echoing the attitudes she has heard from several audiences. “I fucking wrote that comic, asshole.”

Additionally, female writers like Kelly Thompson, author of comics like “Rogue and Gambit,” “Jessica Jones,” and the currently-releasing “Birds of Prey,” are finding ways to subvert and avoid the tokenization of female characters in their own stories.

“I like to personally play with the whole token female character on a team by sort of inverting it,” Thompson said. The team she invented had only one male on it. “I was like, that’s fun, though, because that’s like a fun inversion of what we always used to see.”

A sexualized void

As superhero comics grew in numbers from decade to decade, a pattern of sexualization of female characters — one that began all the way back with Wonder Woman — arguably grew along with them. Female characters being diluted to sex appeal was something that just kept coming back, time and time again.

Take, for instance, the DC hero Starfire. Starfire is a character with a rich history, and complex characterization. After her debut in 1980, she made a name for herself in “The New Teen Titans” in 1982, and has stuck around ever since. It can be hard, though, to read a story about Starfire and ignore her costume — or lack thereof.

In a 2011 event, DC restarted all of its books back to Issue #1, in an attempt to simplify its lineup. In doing this, many characters — both male and female — saw new backstories, teams and costumes. Starfire was one such character, and she got the whole treatment. She was given a changed history, placed on a new team (in a book written and drawn by men), and re-outfitted into what can barely be considered a costume, given its lack of fabric.

As @ThePandaRedd put it, it’s “like three pieces of tape.”

This look would be demeaning enough on its own, but with the changes made to Starfire’s character, the once exuberant, full-of-life character was stripped of all her memories.

“They made her the definition of the ‘born sexy yesterday’ trope,’” said @ThePandaRedd in a video exploring the character’s backstory. “Too naive to know what basic Earth fucking customs is, but … definitely fuckable. Trust me, they want you to know that last part.”

Knight explained that as a woman reading comics, she often feels a sort of whiplash, particularly when reading a male-written comic about a female character.

“You’re flipping through a comic and then you see just like the most gratuitously and weirdly sexualized, violent splash page you’ve ever seen in your life,” Knight said. “You’ll be like, ‘Oh, this is fine. I’m having a great time,’ and then you’ll turn the page … Things can flip very suddenly.”

Of course, there is not anything necessarily wrong about occasionally portraying characters — male or female — in a more sexualized manner. However, that has to be balanced with actual characterization.

“I’ve got no problem with cheesecake [the often-gratuitous sexualization of women], I just think it has to be executed correctly,” said Thompson. “You have to balance it, you have to control the tone of what you’re talking about, and why.”

Knight said that she will often notice a difference in how male and female writers portray female characters, and that this difference does change how she feels reading the book itself.

“Does the author view the female characters as characters, or are they there as you know, set dressing?” Knight asked. “Does it sound like they’ve ever met a woman before in their life? Or, like, did they, I don’t know, wander out of like a teen movie from 1995?”

For Thompson, it comes down to respect.

“Assuming that we’re reading these books because we love these characters, you should treat them with respect,” Thompson said. “And I feel like the way that female characters, it seems especially, get treated, and some of that stuff doesn’t feel very respectful and feels a bit out of step with how things have moved forward.”

A disrespected demographic

Unfortunately, there are many — readers and industry professionals alike — who are disrespectful and dismissive of not just female characters, but of female writers and artists too.

Following the reboot that gave Starfire her new costume, there were 52 books being published by DC. Of the writers for those original 52, only one was a woman, with Gail Simone writing “Batgirl” (and co-authoring another title with a man).

In 2011, a fan confronted then-Editor in Chief of DC Dan Didio at San Diego Comic Con about this sudden drop from 12% to 1% of writers being women. Didio simply responded, “Who should we be hiring? Tell me, right now.”

Of course, the audience did, shouting back names like Alex DeCampi and Nicola Scott. It took until May 2012 for Scott to get hired on, and she became only the second woman to be working on the New 52. By the event’s end in May 2015, roughly 20 women total had been writers or artists on DC books. While this is an improvement, it is still very little compared to the male numbers.

And it is not like women did not try to get hired on more books — they just were not picked. For instance, DeConnick shared a story about how her gender prevented her from writing a book a male colleague with a lot of sway recommended she helm.

A battle behind the screens

Even when female writers are given opportunities, they have to contend with the same social media hate that female comics fans experience — and usually far more publicly, and with far greater effects.

“I feel like there’s a big push on social media to basically vilify any writer who doesn’t do exactly what you think they should, and I think that it very, very much hits female writers in a way that it doesn’t hit male writers,” Brenneman said.

DeConnick has become disillusioned with the barrage of misogyny that has defined what is known as ComicsGate.

“I just don’t have the energy to be so online anymore,” DeConnick said.

ComicsGate is a movement of primarily male fans, loudly and often proudly pushing back against any gender diversity in the industry, both behind the scenes and on the page — a movement that got its start mainly because of a drawing of a shirt.

In 2016, a lesser-known female character Mockingbird got a solo ongoing — a series that has books released at regular intervals starring a specific character — by prose writer Chelsea Cain, known then for her humor and thriller books. Unfortunately, after only a couple issues — well before these comics could be collected in one book, rather than a few separate magazine-like issues — the series was canceled. This was in large part because people didn’t pre-order it (for a variety of reasons, not just lack of interest, but seemingly sexism too).

The book later saw success (hitting #1 on Amazon for Graphic Novels at one point) in a “non-single issue form,” as it did better with all the issues collected in one book, rather than each standing alone. By then, though, Cain had already been dragged through the mud in what some consider to be the comics equivalent of the infamous “GamerGate.” Perhaps the most famous aspect of this Mockingbird series is a single cover, wherein the title character wears a shirt reading, “Ask me about my feminist agenda.” This choice certainly made a statement, though many criticized it, and Cain herself, for the progressive message it sent.

“For the most part, that art [comics] has always been this very progressive leaning area,” Brennaman said. Despite the industry’s many problems, there are several ways comics have been extremely progressive. Captain America was punching Adolf Hitler on the cover of his first comic well before the United States even officially joined World War II, for instance.

“I think for a lot of people, it’s easy to forget that as long as it’s hiding behind the veneer of flashy superheroes, punching and kicking things and big explosions,” she continued. “The moment it’s put in their face though, and spelled out for them, there’s something that clicks … It’s just kind of sad that that’s how that spiraled out of control. And it’s probably one of the worst discoveries of how to use the medium ever.”

DeConnick has seen the negative impact of ComicsGate firsthand, repeatedly emphasizing how “exhausting” these interactions can be.

“There are people in that movement who believe what they’re being fed,” said DeConnick. “I don’t blame them. I blame the leaders who are manipulating people’s emotions and fears for their own personal profit, and taking things out of context and misrepresenting them deliberately in ways that don’t stand up to even the most basic of interrogation, and it’s exhausting.”

One such leader is ex-DC illustrator Ethan Van Sciver (who, interestingly, was the man Simone co-authored a New 52 book with). For years, he has taken to social media to make statements like, “Marvel is adding too many females to superhero teams … For every 3 males, a maximum of 1 female … This is Law.”

Once, he point-blank admitted, “I’ve actively worked to explain why Women in (superhero) Comics is objectively terrible.” It is worth noting that the point of that post was him specifying this applies to “most” women, not all, but even then, the generalization is harmful.

Though the movement never really went away, ComicsGate was put back in the spotlight in 2024 by a series of tragic events. In March, two women came forward with stories of sexual misconduct shown toward them online from comic artist Ed Piskor. On April 1, Piskor committed suicide after posting a statement blaming those who came forward against him, or criticized him and his behavior online.

Following this, ComicsGate took to social media to not only further place the blame on the two women, but to make a statement about women in the industry at large.

“Spurned women and their simps (usually identifying themselves as male feminists) want you dead and nobody is coming to help you. Protect and stand up for yourself, fellas. Don’t talk to anyone under 18 in a sexual manner and don’t hire or be advised by spurned women!” posted ComicsGate supporter @JonMalin.

In light of these events, Sciver made a dirty joke about the Believe Women movement, to which user @troiaas responded, with an air of irony, “it’s time to bring back guillotines i think.” Again, that humor is admittedly dark, but there seemed to be no malice behind it. Sciver disagreed, though, saying “This is why women should be confined to kitchens and bedrooms. Violent fantasies like this. Ladies, make babies and sandwiches and hush.”

“ComicsGate is still out there,” Thompson said. “They’re still doing all the same things that they were doing when ‘Mockingbird’ came out. They’re making their yelly YouTube channels, and they’re screaming about these things, but they don’t read these books. And they don’t care about these books. And I don’t know why anyone would listen to them, honestly.”

Thompson recounts mostly positive experiences in the comics industry itself — she said the occasional times where she thinks her gender took her out of consideration for “bigger, sort of front-facing projects” were balanced out by the times she has been “on a shortlist of people who are very right for a certain kind of book.” Still, she fears what could happen, given what toxic fans have done and continue to do to female writers.

“I’m not filming this interview and that’s a big reason why,” Thompson said. “Because I’m a fat woman, and the second I put myself out there it becomes about this, and about attacking the way I look or how I am or whatever, instead of just letting it be about the work.”

While toxic fans taking to social media can definitely be harmful to the people they are attacking, it is rare that their toxicity will actively impact the product they are criticizing as it’s being made. However, that is often the case in the comics industry.

A complicated model

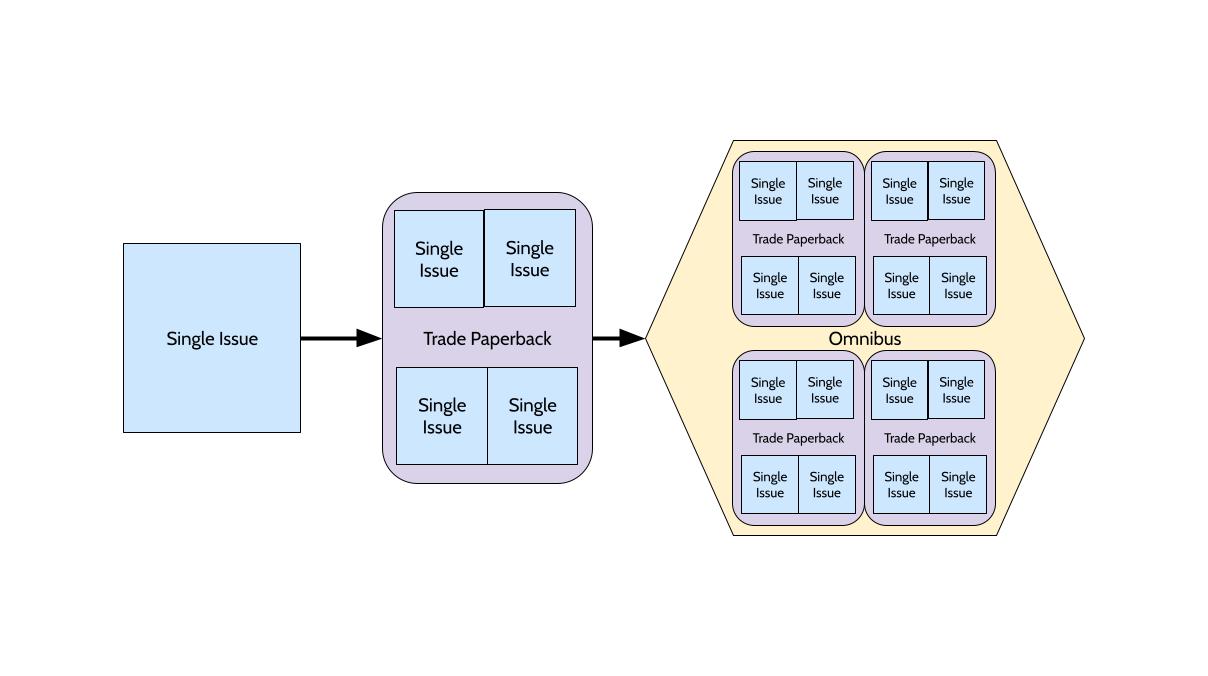

Physical, paper comics (as opposed to digital comics, which will be discussed later) can be purchased in three main formats: single issues, trade paperbacks (interchangeable with graphic novels, though the latter term has other meanings too), and omnibuses. The best way to think of it is like a television show. A single issue is one episode, a trade paperback is one season, an omnibus is a full series.

Like episodes of a cable television show, new single issues release weekly. But, you can also find what are called back issues, which are essentially episodes of a television series from a decade ago that you can watch on demand.

You may assume that buying comics is the same as buying standard novels — you walk into a store, find what you’re looking for, purchase it and leave. It is intuitive, it makes sense. Unfortunately, comics don’t quite work that way. You are more than welcome to walk into a comic shop, pick up a single issue or graphic novel, purchase it and leave. But, that purchase means little in the eyes of companies like Marvel and DC.

“They don’t go to every comic shop and go like, ‘how many books did you sell?’” said @ThePandaRedd, who ran a comic shop with his family around 2014. “The bought-books count is usually like, ‘How many of these issues did comic shops buy?’ … It’s not like, ‘Oh, 50,000 copies got sold through comic shops.’ It’s ‘50,000 copies were bought by comic shops.’”

When you buy a comic, the money you spend does not go directly back to the company that published it. Instead, that money stays in the comic shop. The money that the publications themselves see is from the shop — sometimes through a third-party distributor.

About once each month, shops order the comics which will actually be purchased by customers a couple months later. If a comic shop orders a book in January, that book is probably scheduled for a release date in the spring.

The person ordering has to determine which comics will sell better when they hit shelves down the line, because there is typically no way to return a comic once it’s been purchased from the company. The only next step is to put them in an archive of other past comics for sale, and hope someone buys them. Unfortunately, this is not a solid backup plan.

“The profit margin on a comic is very slim, and there are literally hundreds of new comics that come out every week,” DeConnick said. “Contrary to popular belief, very few comics go up in value. So those comics that have already had a very low profit margin lose their value a week after they come out … as much as, like, a new car loses its value as soon as it drives off the lot.”

On top of that, back issue archives within a comic shop can be incredibly daunting.

“You’re going down to something that … looks like a mausoleum to paw through white boxes with an inch of dust on them,” Knight said. “It’s intimidating, even if it’s like the most lovely well lit modern space in the world.”

So, comic shop owners need to be in-tune with their readers, actively thinking about what books will sell well. And, if they miscalculate, there’s nothing to be done.

Joseph Guarracino worked at Not Just Comics, a comics, cards, and general science-fiction store in New Rochelle during the late ’80s and early ’90s. As part of his job, Guarracino was responsible for ordering new comics on a regular basis.

“You really have to understand the medium,” Guarracino said. “The two guys who ran the store … had no idea. I understood the medium, and what to buy, and what was popular.”

This need to be in tune with what the opinions of the consumer base are at any point in time is part of why pull lists are important. A pull list is essentially a way to subscribe to ongoing comics — in fact, some shops just call it a subscription. It is a list of every currently-releasing comic series that you want to ensure you own in full. As each issue releases, the comic shop will make sure to order you a copy.

I created my first pull list in my reporting, at the shop Forbidden Planet on the Lower East Side of New York City. When I went to sign up, I was given a sheet of paper, with several blank lines, on which I wrote the names of several comics I wanted to read as new installments were added. I included titles like Thompson’s “Birds of Prey” and “Ultimate Spider-Man” by Jonathan Hickman.

Then, on or following the first Wednesday (the day of the week when new issues release) after you set up your list, you return to your comic shop and pick up the new issue of each of the titles you signed up for if a new one released that week. The first time I went to get the books on my list, I had the next issues of “Birds of Prey” and “Ultimate Spider-Man” waiting for me at the counter, along with several other titles I ordered.

You purchase all the books then and there — no hassle, no searching the shelves for that last remaining copy of the newest book. Then you come back a week later, rinse and repeat. When I walked out with my first pull list haul, I was astonished at how easy the entire process was.

Not every shop will have the exact same process, of course. For instance, Forbidden Planet will cancel your pull list if you don’t collect your books at least once a month. Other shops might have different policies on how often you should pick up your comics.

You don’t technically need a pull list to read books in their entireties. Many people will purchase single issues right off the shelves — shops will usually have a whole section devoted to recent releases. But, you have no guarantee that the comic you want to buy will be on that shelf for purchase. If it’s a less popular book, for instance, the shop may have only ordered a little more than exactly enough to fill people’s pull list requests, out of fear that the other copies won’t sell. They know for certain that the pull list copies will be purchased. It’s hard to take that kind of risk on what could be a less-popular book.

“You have to buy [books] for the people who were subscribed, and then you have to buy for people who just walked in the door,” Guarracino said. “So you keep track of what you sold the last time and what you have extra of.”

This goes the other way too. The shop may have only ordered a few copies of a new, underground book, and it turns out that everyone who does not have a pull list wants to buy it. Since the shop didn’t order enough copies in the first place, it can’t sell customers more, and they have to take their business elsewhere. Guarracino called it “a little bit of an art and science.”

“There are things that we will never see because people thought it would be stupid before they ever actually read the book,” said @ThePandaRedd. “And there’s also things that will get way more hype, because they just kind of look or sound cool. That will trample over those smaller stories.”

Under this model, the books with the most copies sent to shops are the ones considered successful, regardless of how many people actually buy those copies. This means that if comic shop workers don’t think a book will sell well, it likely won’t have the chance to prove them wrong, as only a scant few copies will be available for purchase in the first place.

“If nobody bought a book, we [the comic shop] would stop buying the book, and if we stopped buying the book, that means the distributors aren’t selling the book,” said @ThePandaRedd. “So when people don’t buy a book, it’s just going to get canceled, and good stories will never be told, and runs will end when they shouldn’t.”

A system spread through word of mouth

Going to comic shops has historically been an uncomfortable experience for women. There’s an old adage of women walking into comic shops and either being spoken down to, or ogled at like eye candy, and it is an experience that continues to this day in some stores.

“I think a lot of people, especially newer fans, are nervous to go into a real local comic book store and ask questions,” said Knight. “Are they going to be mean to me? Am I going to look like I don’t know anything? You know, like the stereotype of ‘The Simpsons’ comic bookstore.”

This may not seem like an accessibility issue at first, as there are several other ways to acquire and read comics outside of buying them at a physical shop. Online retailers can bring you physical comics without needing to actually go into a store, and subscription services like Marvel Unlimited or DC Universe Infinite give you access to an extensive library of online comics for a fee.

“If you don’t want to deal with someone and go to a store, you can buy almost everything digitally,” Thompson said, though she personally has had more positive experiences than negative.

It’s easy to assume that, given the relatively positive experiences in comic shops described in this section, things are getting better. In all honesty, I can’t say for sure whether they are or not. Thompson likes to believe they are.

It’s worth noting, though, that the reason I was able to interview many of these people is because they have made their passions for comics public. It is very likely that those who have had the worse experiences — the “horror stories” Brennaman has heard from peers — have been discouraged from such a public presence in the comics space.

But, if you are not going in-person to a comic shop you are both not using a pull list, and not giving yourself the best opportunity to learn about them. If you Google “What is a pull list?” you will find several guides and how-to articles. However, without knowing that you should Google that, you may not even realize that there is this way to pre-order comics in the first place.

People typically learn about pull lists via word of mouth, or other similar means. Personally, I’m deeply engrossed in the world of superheroes, and I only learned of the existence of pull lists through a mention of the pre-order-reliant business model of comics in a podcast. Before then, I was going to Forbidden Planet at least twice a month, buying mostly trade paperbacks, and figured that and my Marvel Unlimited subscription were the best ways to engage with the medium.

As a regular in her more welcoming local comic shop — which Knight acknowledges she is “pretty fortunate” to have access to — Knight was told about pull lists directly.

“When I was getting into comics, I would go in and basically buy whatever looks interesting,” Knight said. And so the guy at the counter, we got talking, and he suggested, ‘Oh, you should set up a pull list.’ And so I had that explained to me.”

Again, because these pre-orders are happening far in advance, the purchases and opinions of those without pull lists have less of an impact on the longevity of a book than those of the people who do have them.

Since companies like Marvel and DC are primarily seeing the opinions of those who do go to shops in-person when looking at sales numbers, the opinions of those with pull lists could make or break a book’s future, regardless of how well the book sells post-publication.

For example, going back to Chelsea Cain’s “Mockingbird,” it’s been established that though the book did not sell well enough for it to avoid cancellation when it was releasing issue-by-issue, it saw massive success on Amazon in trade paperback format.

There is not a definitive way to know for sure, but it is entirely possible that this is because the opinions of women readers — who want to read comics about people like themselves but were less likely to be putting this book on a pull list — were not considered prominently enough. Again, this is just conjecture, but even its plausibility emphasizes how broken the comics industry is.

“Things would get canceled before they even came out because of pre-orders, right?” said Eliot Borenstein, a professor at NYU who has taught courses on comics. “So that was terrible all around — specifically terrible for women-led comics, but just also really bad in general for doing anything new. And since women-led comics are almost always something new … they kind of get, like, a double hit from it.”

A powerful fanbase

Once, there was a movement of fans strong enough to convince Marvel to greenlight and regularly publish a female-led solo ongoing — “Captain Marvel,” specifically the run written by DeConnick.

Fans of the “Captain Marvel” movies may not know that in the comics, Captain Marvel was originally a male hero. Not only that, but the character Carol Danvers — the current Captain Marvel, and the one featured in the MCU — was not even the first woman to be Captain Marvel. Carol operated as Ms. Marvel for the majority of her many decades in comics, before DeConnick’s run, which solidified her as the current Captain Marvel.

Much of this was the result of hard work from DeConnick, who created and was very publicly at the helm of a large, prominent group of women fans called the Carol Corps.

“I would never counsel anyone to do what I did,” DeConnick said. “It was stupid. But I lucked out. And it worked. And what I did was … I spent my own money to do marketing for a billion-dollar company.”

She explained that from the start, her “Captain Marvel” run was not set up for success.

“The rule of thumb at the time was, you had to have an A-list writer, an A-list character, or an A-list artist,” DeConnick said. “C-list writer, C-list artist, B-list character. We were fucked.”

So, DeConnick took her book’s fate into her own hands, and found an opportunity to foster a welcoming, inclusive space for women in comics.

“A lot of women were teed up to reenter the industry at the time, both as consumers and as professionals,” DeConnick said. “And I say reentered deliberately, because at the time there were a lot of people with a very short memory about comics who felt as though women had never read comics in any numbers. And that is just patently untrue.”

Naming this group the Carol Corps, DeConnick began by making membership cards, which she would hand out at conventions and book signings. Over time, the Carol Corps just kept growing.

DeConnick said that the group did help “Captain Marvel” sales surpass original expectations, but that the numbers were not as high as they could have been. What really mattered, though, was that, “We were just visible.”

“Whispers about the cancellation of Captain Marvel, or even that of other diverse titles, brought the specter of the Carol Corps, a threat to editors and publishers that might dare to test their loyalty and wrath,” wrote Caitlin Rosberg in an article about the group.

Carol Corps members were vocal about their love of the book and about how much they wanted it to continue, and it did. Visible, indicated interest was high, and so the book survived even beyond DeConnick’s own expectations.

“I was so convinced that the book would be canceled, I did not plan past the sixth issue,” DeConnick said. “So when they told us we were gonna go to 12, I was like, ‘Shit, I need to figure out a story.’”

Now, though, this version of the character has her own movie.

“Captain Marvel is a really interesting example because … [today] she’s being bolstered by the movie, but the movie never would have happened if there hadn’t been this groundswell of support for the comic,” said Borenstein.

This was a glimmering moment of hope for women-led ongoing books, but the amount of work, time and money DeConnick took on to make it happen would be unsustainable for an entire business.

A broken system that breaks an industry

The comics industry is, in essence, experiencing a cycle. The opinions of those with pull lists — often men, since women are seemingly less likely to be comfortable enough in a comic shop to ask — are taken into consideration. So, books for, by, and about men endure, whereas female-led books — books about someone that is not like them — are canceled.

This emphasizes the masculine focus of the industry, perpetuating and giving evidence to the idea that comics as a whole are for, by and about men, which does nothing to help women feel safer in comic shops. So, women may feel safer continuing to read comics with alternative methods like ordering trade paperbacks or omnibuses online, but those purchases are not taken into account when deciding the fate of a given book. So the cycle continues.

On top of this, there is the economic impact of a trend that often comes up in toy marketing, but applies to mediums like movies and comics too. Women are far more likely to buy products targeted to men than men are to buy products targeted to women. So, it makes economic sense that there are far more male-written, male-centric books than female-written, female-centric ones.

“[Women] don’t pay any kind of psychic cost or social cost for cross identifying,” said DeConnick. “[Men] pay a price for cross identifying … If you market to men, your marketing dollars are spent better, because you will absolutely get women readers, consumers, whatever. If you market to women, you absolutely will not get men.”

Additionally, the alternative methods people can use instead of pull lists or in-shop purchases — notably subscription services and piracy — have negative impacts on the industry, particularly women writers and artists.

A comic collection in your pocket

Think of subscription services for comics as streaming services, to go back to the previous television show analogy. You pay a fee (typically monthly or yearly), and get access to a large library of comics. Marvel and DC each offer their own platforms — Marvel Unlimited and DC Universe Infinite, respectively.

Some digital comics are simply scans of books which are also sold in person. For instance, I could open Marvel Unlimited and read the entire 26-issue run of “The Unbelievable Gwenpool” by Christopher Hastings and Gurihiru, despite only physically owning a couple of those 26 issues myself.

Other titles, though, are digital-only (or occasionally digital-first, then printed afterward). DC primarily publishes digital-only comics through Webtoon, a site which anyone can access free of charge. Marvel, though, keeps many digital-only comics behind Marvel Unlimited subscription paywalls.

There are certainly benefits to subscription services. Namely, they are far cheaper than physical comics — in fact, some webcomics (like those on the app Webtoon, which DC partners with) are even free.

“Webcomics — uber popular right now,” @ThePandaRedd said. “Way more popular than buying physical comic books … because it’s easier to access. You get a free app … You can just download a digital app and wait a week and it shows up. You can’t do that with comics.”

Some people actually buy digital comics as their physical counterparts release from week to week, while others will wait a month or two for the newest releases to be added onto the platform they are already subscribed to. Think of it like buying a digital release of a movie, or waiting it out for it to come to streaming.

Subscription services also offer readers a massive library full of comics, without requiring people to physically go to a comic shop, and search for what they want.

“It is a friendlier method, because it’s all in one place,” Knight said. “You don’t have to go into a comic book store, and maybe meet the weirdest guy you’ve ever met in your life. And a lot of [webcomics] are kind of lighter stories that are friendlier.”

However, the rise in digital comics has hit creators hard. Thompson is the co-creator and writer of one of Marvel’s most popular digital-only comics — “It’s Jeff!” The comic is about a cute landshark named Jeff (once the character Gwenpool’s pet), and his misadventures around the Marvel universe.

Despite the comic’s massive popularity, Thomspon said she doesn’t get royalties for it, and that insufficient tracking methods prevent her from being compensated in a way that reflects the book’s readership.

“I do worry that me saying ‘yes’ to Jeff and continuing to do it sets a bad precedent,” Thompson said. “Jeff has been read by millions of people, and if I told you how much money I’ve been paid for every ‘It’s Jeff’ thing I’ve written, you would be shocked.”

This paycheck for digital comics, though, is arguably more important now than it ever would have been before (had the technology existed in other eras of comics), as digital comics make pirating far easier.

A Pirated Loot

Economically speaking, the comics industry is not the most stable and reliable.

Thompson and DeConnick both explained how important it is to “love comics” in order to be part of this industry, with the former talking about it from the creators’ perspective, and the latter from retailers’. “Nobody goes into comics retailing because they think they’re going to retire off of it,” DeConnick said. “They go into comics retailing, because they love comics.”

Unfortunately, as Thompson notes, pirating — or, the illegal duplication of a piece of media created or owned by someone else — poses a major threat to this industry.

“Between piracy and how difficult [comics] are just to access and find … you really have to love comics to stay in it,” Thompson said. “And even that sometimes isn’t enough.”

When comics are pirated, the creators and retailers see no royalties, no compensation, no money. Additionally, the readers of pirated comics do not count in the eyes of companies when considering whether to cancel or renew a book.

For Thompson, it all came to a head one day when she took to social media, pleading with her followers to pre-order an independent comic she was writing. Without pre-orders, the book was going to get canceled. There needed to be indicated interest in it from an economic perspective for it to survive.

One commenter asked where they could read the book, and another person responded with a link to a piracy site. Ironically enough, the person who sent the original commenter to the piracy site had expressed surprise that the book would be ending at only five issues.

“Yeah, I mean, if you wonder why comics like The Cull are hard to keep going for more than 5 issues… THIS is a big part of why,” Thompson replied on X. After hearing this story, @ThePandaRedd agreed with Thompson, saying that piracy is “killing the industry.”

DeConnick, however, is less concerned about this piece.

“I don’t worry about pirating at all,” DeConnick said. “I mean, it’s annoying … But I know a lot of people who pirated a lot of books, and … would end up buying those books when they had the money to do it. And I think it helps spread a lot of word of mouth.”

Knight admitted that she finds the piracy sites to have more complete comics libraries.

“My issue is with digital comics that the piracy website should not have better back catalogs than the official publisher,” Knight said. “Marvel Unlimited has back catalogs that will skip 20 whole issues in the middle of a series for no stated reason.”

Unfortunately, pirating has become the only viable option to a lot of people. At its core, it has the exact same impact as digital comics, just without virtually any financial compensation or readership numbers whatsoever getting back to the source.

And for many people, pirating may have become the most financially viable option — especially if they are being discouraged from going to in-person comic shops. Or, it could be the easiest way for them to take a first step into comics to begin with, if they don’t know that these sites with their vast libraries are not official, legal resources.

Rises in both digital comics and pirating are leading this already economically shaky industry to an even worse place. Meanwhile,many readers — particularly female readers — are being alienated from other options. What else is there to do if you want to read comics and don’t feel welcome where you’re supposed to go and buy them? But still, pirating actively contributes to the continued decline in the stability of the industry.

A way forward?

The gender disparity in comics clearly has a wide reach, as it always has.

Diana Schutz is a former editor in chief of Comico, and worked as an editor for Dark Horse comics for 25 years. Still, she remembers a comment from a customer on her first day working at a comic shop in 1978.

“My very first day on the job — at The Comicshop in Vancouver, BC — a store customer, who was also a friend of the two (men) owners, came into the shop, saw me, and asked, ‘Who’s the skirt?’” Schutz remembers. “It could only get better from there, right?”

And as much as some things have improved since, others simply have not. Shutz recounted how “When I first began working in comics (way back in 1978), many of the doors were just… closed to women.”

Decades later, DeConnick was rejected from helming a big-name book, simply because of her gender.

Things cannot get better if women continue to be excluded from this space. Unfortunately, women continue to feel uncomfortable in comic shops, and men continue to be marketed to directly, reinforcing the idea that comics are for, by and about men.

Perhaps there is a world of support for these women-led, women-written books, but that support comes from people who have never heard of a pull list — something perfectly reasonable, given that the system’s existence is shared mostly through word of mouth.

“If you’ve got the interest, and the time, and your finances are stable enough that you can just set up a pull at a shop … that’s the best thing you could do for the comic creators you love,” Thompson said. “That’s how their books still get made, and renewed and all of that. It’s an archaic kind of a vibe, but that’s all we got.”