California Central Valley: Write in Your Identity

A Census meeting in California’s Central Valley. Central Valley Immigration Integration Collaborative.

California’s Central Valley has been home to Dr. Jesus Martinez and his family for over 29 years. Martinez was born in Mexico and feels a strong connection to his country of origin. When asked to check his race for the U.S. 2020 Census, he chose to write in Mestizo, which means a combination of indigenous and Spanish heritage.

Martinez, who works at the Central Valley Immigrant Integration Collaborative (CVIIC), compared the US Census to the one offered by Mexico, which provides detailed categories for a variety of Mexican indigenous identities. Those categories are easy for members of the Latino population to understand, said Martinez. In contrast, the race box in the U.S. census is confusing and has troubled many residents of the Central Valley. In 2010, CVIIC organized a number of focus groups to take a closer look at the residents’ reactions to the census questionnaires. After analyzing the responses, Martinez noticed the responses had one thing in common: nobody was happy with the questions.

“They didn’t feel represented in the questions,” said Martinez. So his group suggested residents do something about it. “If you felt uncomfortable with one of the categories that were there, then write in something that you feel comfortable with.”

Martinez believes the Census should be a place where people can express themselves and their identities. He and his staff explained to the residents that they were free to choose among the different options and there were no right or wrong answers. In fact, the race of individuals should be self-identification of the person’s race, as it is stated on the Census Bureau’s website.

However, they didn’t want to influence people’s choices by telling them what to check, either. “Some organizations promoted the idea of writing in, for example, Mixteco,” Martinez said. Mixtecs or Mixtecos are indigenous Mesoamerican people of Mexico. “But as an organization involved with the census, we could not propose or inform people or encourage them to respond in a certain way.”

Martinez often found that he was in a pickle when asked to choose between individuality and social norms. Like him, many residents in Central Valley have immigration backgrounds and the key to integration work often boils down to self-identification. Hispanic is often not the preferred identity for people who share Mexican origin or are from Latin America, said Martinez. What Hispanic really means to them is that a person has a colonial relationship with Spain. But the majority of us here, Martinez said, have indigenous roots.

A question then came: should people embrace a monolithic label to integrate into a new culture that differs from their own identity narratives?

Brooklyn, New York: Check the Box with Hesitation

Ray Aguilar works as an EMT at Brooklyn Hospital Center. When filling out the 2020 census form, Aguilar checked “Yes, Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano” under the question about the Hispanic origin—with hesitation and reluctance.

As a first-generation immigrant growing up in Brooklyn, Aguilar said that his parents still identified themselves with their country of origin. He felt somewhere in between his Mexican roots and American nationality. “I don’t feel American enough, but then in Mexico, I am not Mexican enough,” said Aguilar.

When he looked at the racial and ethnic questions, Aguilar said he feels very uncomfortable with terms like Latino or Hispanic. “The term, Latino and Hispanics, are imposed terms, you know, and they are not terms that we use to describe ourselves,” Aguilar said. “That’s why a lot of times people prefer to use a term that is based on national origin.”

But, his feelings about the census race box were mixed. Aguilar admitted that checking the Hispanic origin box based on the norms brings him a sense of belongingness. Whenever he visited his family friends in Mexico, he felt regretful for not being fluent in indigenous languages or affiliated with a tribe.

The power of language in connecting people made him believe that forming unity among Spanish-speaking people matters more than the inner differences. Hispanic or Latino populations have been disproportionately involved in poverty, said Aguilar, and the health resources in our communities are not the same as those in the White communities.

“It’s important to have terms that unify us as Spanish-speaking people because we have different experiences as a population of the United States,” said Aguilar.

As a health worker, Aguilar’s beliefs about forming unity by language stem from his real-life experience—it’s much easier for him to build connections with patients who speak Spanish and provide medical care against the clock. But does the end to unifying immigrants justify the means of using uniform identification? Is this what the Census was designed to do?

Conflicting Identities of Census: Statistical Tool or Social Narrative?

A census enumerator’s records from the 1790 Census. Photo by National Archives.

In 1790, Census counting became a constitutional requirement in the U.S. “The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner, as they shall by Law direct.” Since then, the census has been an integral part of American policy, as it provides data for the distribution of congressional representatives and federal funding.

From a statistical point of view, census data provide a longitudinal assessment of population density, the size of the labor market, and the nature of the family structure. For the general public, the census is considered as something between a civil duty and a petty intrusion. But recently, the census has also become the source of new narratives about social identities.

With so few constitutional details, the census has had to change a lot, depending on American society’s demographics and attitudes. Between 1790 and 2020, 600 separate census questions have been asked. Examining them yields information about how American society has counted and considered its citizens. One question that has been asked from the start is about race, the longevity of which serves as proof of its importance. A question about race makes sense for a country of immigrants. But what happens when the sources of migration, and the self-definition of the migrants, grow so large and various that the number of categories becomes unwieldy? The story of the race box shows how the nation has explored its complex identity through trial and error.

Racial categories on the 2020 Census. Photo by MGN online.

At first, only free white males and females were counted. In 1850, a separate color question was inserted, providing three categories to choose from: White (W), Black (B), and Mulatto (M). More racial categories of Asian and Hispanics appeared on the census along with waves of immigration: Between the California gold rush in 1849 and 1882, a large group of Chinese immigrated to the U.S., and “Chinese” was added as a subsection in 1870, which was followed by the addition of “Japanese” and “Indian” in 1890. Through the 20th century, more Asian racial categories, such as “Filipino” and “Korean”, were added.

The “Hispanic” category didn’t appear on the census form until 1970. A “Mexican” race category was included once in the 1930 Census when forms were filled out by census-takers during home visits. Yet, prior to 1930 and between 1940 and 1970, enumerators were instructed to list Mexican Americans as White.

The “whiteness” of Mexican Americans was due to protests about citizenship for people of Mexican ancestry. Between 1790 and 1952, the boundaries of whiteness were a precondition for naturalization. European immigrants were judged to be white, whereas Asian immigrants were judged to be non-white. By law, Mexicans are eligible for naturalization. But unlike European immigrants, Mexicans were eligible because of relations and treaties between the U.S. and Mexico. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) granted U.S. citizenship to Mexicans in the newly incorporated territories. For instance, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld a citizenship application from Ricardo Rodriquez in 1893 not because he was white but because of U.S. treaties with Mexico.

In 1935, a New York federal judge upheld an immigration officer’s denial of three Mexican immigrants’ applications for citizenship on the grounds that they were not white, but rather individuals “of Indian and Spanish blood.” Mexican Americans protested and filed petitions to reverse the decision. To quiet the controversies and seek better relations with Mexico, the Roosevelt administration convinced the judge to reverse the decision. Accordingly, the Labor Department ordered officers to treat all Mexican immigrants as White. The Census Bureau took heed of the guideline by the Labor Department.

Despite Mexicans’ claims to whiteness in the 1930s and 1940s, the reality hit hard. Between 1929 and 1936, about one million Mexicans and Mexican Americans were repatriated to Mexico, because of fear and anxiety over Mexicans taking jobs away from white Americans. In Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, authors depicted how Mexicans were deported no matter whether they just arrived with documents or lived in the U.S. for generations. “That population was regarded as not being part of the American community,” Francisco Balderrama, a co-author of the book, said in an interview with TIME.

Even for those who stayed in the U.S., few Mexican Americans were eligible for Depression relief because of their occupation status. Back then, many Mexican Americans were working in the agricultural and domestic industries where, according to the Social Security Act of 1935, workers were excluded from receiving social security benefits and unemployment insurance.

Between the 1940s and 1950s, Mexican American Civil rights movement started to arise. Three major court cases highlighted the movement during the period. First, Mendez v. Westminster (1947) set the legal precedent for ending educational segregation between Hispanics and White Americans as unconstitutional. The next year, Perez v. Sharp (1948) challenged the ban on interracial marriage, which was found by the court to violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Another case, Hernandez v. Texas (1954), further challenged segregation in the courtroom. In the Southwest, Mexican Americans were excluded from serving as jurors prior to the 1960s, and legal advocate for Pete Hernandez, who was convicted for murder, argued that he was discriminated against because there were no Mexicans in the jury of his trial. The then-Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled in favor of Hernandez and required he be retried by a jury consisting of his peers.

After the successes of the black civil rights movement in the late 1960s, Mexican-American activists initiated the campaign, known as the Chicano movement, to gain political power. Drifting apart from the previous efforts to be recognized as a class of white Americans, leaders in the Chicano Movement decided to embrace their heritage. Chicano was long treated as a racial slur. By adopting “Chicano” as their identities, those who joined the movement took pride in their Mexican heritage, especially their indigenous and African roots.

The Chicano movement consisted of several movements, including fights for farmworkers’ rights, land reclamation, and the creation of bilingual and bicultural programs in the southwest schools. Jimmy Patino, who is a Chicano & Latino Studies professor at the University of Minnesota, commented in an interview that the core of the Chicano Movement was about self-determination. “The idea that Chicanos were a nation within a nation that had the right to self-determine their own future,” said Patino.

Unfortunately, poor racial statistics made it hard for people from Mexico and Latin American to gain fair representation in economic, political, and education domains. The demand for better statistics became an important impetus for refining the census race box.

Before 1970, the prevailing method of identifying Hispanic households during home visits was through looking for people with “Spanish surnames” or people who speak Spanish. The repatriation in the 30s traumatized generations of Mexican American families, as shown in a follow-up study by Balderrama and his colleagues. Descendents of the repatriation hid the past from their children and anglicized their names after coming back. Many ended up marrying people that were not Mexican to declare their independence from the Mexican heritage.

The interviews corresponded to the research findings by Hispanic leaders who vowed to design a better census race box for their people. They noticed that many “typical” first names were disappearing among the Hispanic population in the late 60s. The “surname” method thus not only became an unreliable way of counting Hispanic communities but also diminished the cultural diversity due to the expansion of Anglo names. To address the issue, the leaders petitioned to add a question of Hispanic origin by self-identification. In 1970, a Hispanic origin question was added to the census questionnaires that were sent to a sample of the population.

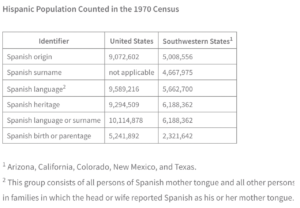

Hispanic Origin Question in the 1970 Census. Photo by U.S. Census Bureau.

However, the question in the 1970 census didn’t work well. Some people who lived in the central or southern United States filled in the “Central or South American”, even though they were not even people of Spanish origin. But there’s a bigger issue than that. When the Census Bureau compared the 1970 count of “people of Spanish origin” with other categories, such as language use, they found that the Spanish origin question performed poorly.

Many Hispanics didn’t identify with their Spanish origin in the 1970 census. Table by Jacob S. Siegel and Jeffrey S. Passel, “ Coverage of the Hispanic Population of the United States in the 1970 Census: A Methodological Analysis,” Current Population Reports, Special Studies, Series P-23-82(1970): table1.

In 1980, the Census Advisory Committee on the Spanish Origin Population was formed to facilitate negotiations between census officials and leaders of Hispanic organizations. From Hispanic activists’ view, technical concerns raised by census officials were merely bureaucratic excuses to avoid political consequences; In the eyes of Census officials, Leaders of Hispanic organizations were opportunists who don’t understand the level of technical sophistication in the census.

The goal of the Hispanic leaders was clear: they wanted to try everything to produce better Hispanic statistics. At one point, they got to know that the lack of demographic estimate of the Hispanic undercut was partially due to the lack of knowledge of Hispanic birth and death rates. The committee members then requested census administrators to meet with officials of the National Center for Health Statistics and representatives of any other relevant agencies to rectify the situation. But for census officials, those complaints were beyond their control and drifted away from the purposes of preparing for the decennial census. Hispanic activists on the committee took their passive attitudes as completely bureaucratic put-offs.

For census administrators, they felt sympathetic towards the Hispanic leaders’ proposal of a self-identification technique. They were well aware of the sentiment—which was expressed wholeheartedly through all the protests and lawsuits against the Census Bureau for inaccurate information about the Hispanic population. But they had their reservations: what terms to use to avoid confusion? who is a Hispanic person anyway? Census officials wanted to make operational definitions of racial categories and find an unambiguous solution. But the task was not easy. Individuals define themselves differently over time, not to mention the fact that people attach different meanings to terms.

The scientists at the Census Bureau, as Harvey Choldin pointed out in his book, lived in two worlds—politics and science. Although the task of obtaining national statistics sounds purely scientific, the fact that the Census Bureau belongs to the federal government assigns political significance to the work.

The dual identity of the census—statistical tool versus social narrative—reveals two conflicting goals of the census: how to make sure the census is statistically feasible and political representative. The conflicting dual identity of the census has continued causing confusion among respondents.

According to 2014 research, Hispanics were shown to be one of the most likely to change racial or ethnic identity from one census to the next. Researchers studied a subsample of 168 million Americans and found that 10 million self-reported that they checked different race or Hispanic-origin boxes in the 2010 census than they had in the 2000 census. The fluidity of those 10 million census answers challenged the statistical validity of the census data.

Moreover, 37% of Hispanics — or 18.5 million people — checked “some other race” in the 2010 census. 2.5 million Americans who said they were Hispanic and “some other race” in 2000 switched to Hispanic and White in the 2010 census while another 1.3 million made the opposite choice.“Some other race” category, mathematically speaking, should be a small residual category designed for overlooked race categories. For those who checked “some other race,” many indicated that they did not identify with a specific racial group or think of Hispanic as a race.

Race isn’t a black-or-white issue. The definition of one’s racial identity is more subtle, depending on the circumstances. While the diversity in census racial and ethnic categories could be a pride asserted, for instance, in the Mexican civil rights movement, it can cause problems when the subjectivity of the terms caused ambiguity, as well as confusion, for both the general public and data experts.

Fear toward Government-Backed Census

There are a lot of motives for one to defy standard racial categories, and racial identity isn’t always a unitary, or even positive attribute, which a citizen is eager to claim. Social Darwinism informed 19th and 20th-century notions of race, culminating in the system of racial registration of Jews and others, used by the Nazis in Germany. With the Holocaust in recent memory, many American Jews objected when a US census question on religion was proposed as a way to better understand the country’s diversity. They were concerned that the government might use the data to monitor them.

Nazis used racial registration to identify Jews. Photo from Getty images.

History proved that these fears were not unfounded. When the Japanese category was added in 1890, nobody anticipated that those data would be used to intern Japanese Americans during the Second World War. Although census data are supposed to be private, Congress suspended these rules in 1942 and used data from the 1940 census to locate Japanese-Americans. This legacy loomed over the Trump administration’s 2019 attempts to insert a citizenship question. History teaches us that you never know whether the government will betray your privacy.

Martinez told me that the majority of the people in the Central Valley were mixed-status families. Mixed status families are families where one or more family members are U.S. citizens or green card holders, who are often children, and some are undocumented without legal immigration status, who are often parents. About 16.2 million people in the United States live in a mixed-status family, and California is the state that has the largest number of U.S. citizens in mixed-status families (1.5 million people).

“If there is a citizenship question included, it would put their families in a vulnerable situation because people believe that the census information that will be collected could also be utilized by the Trump administration for immigration enforcement purposes,” said Martinez.

Martinez’s concerns were corroborated by a study conducted in San Joaquin valley where a lot of Latino immigrants resided. The study showed that adding the citizenship question dramatically decreases willingness to participate in Census 2020 from 84% to 46% of all participants. Among the mixed-status families, legal residents’ willingness to respond also reduced from 85% willingness down to 63%. In their comments on the surveys, many second-generation U.S.-born Latino citizen respondents considered the citizenship question to be divisive and racist.

To make matters worse, the fear may never go away, despite the government’s efforts to dispel people’s doubts about the citizenship question. “The problem is that there have been anti-immigrant policies for many decades and years. It’s not something that emerged with Trump,” said Martinez.

In Houston, Texas, the sharpest declines of self-reporters of the census were correlated strongly with the percent of the Hispanic population, said David McClendon, a data scientist working on census projects in Harris County, Texas.

Around 11% of the local population is not a U.S. citizen and 45% of Hispanics in Texas live with a non-citizen. Harris County stands out in terms of its racial diversity because nearly 70% of the local population is non-White and low census response rates have been associated with fewer non-Hispanic Whites. The hint of a citizenship question on the census form threatens Texans, especially those who are living with non-citizens.

McClendon and his colleagues decided to find out how bad the census response situation was among non-citizens in Harris County. To conduct the analysis, he used citizenship status information collected by the American Community Survey (ACS), a more detailed version of the census that has been sent out to about 3.5 million addresses every year. The facts were shocking: at least 20% of non-citizens had low response scores that exceed the national average in the 2010 Census.

Distrust has been widespread among racial and ethnic minority groups in Texas, said McClendon. The levels of immigration enforcement were correlated with estimates of low response rates by the Census Bureau, as McClendon found out in his data analysis. His finding aligned with recent studies showing that Hispanic households who shared the fear towards immigration enforcement were less likely to trust the government as a source of public health information, as well as enroll in safety net programs in the U.S.

Over time, a pattern emerged: A new racial category would be proposed with the goal of making the census more inclusive. News categories were added to reflect the rapid growth of immigration. Then a backlash would occur from those who feared the terms would be confusing or even used for nefarious purposes, whether in legal or political terms. If the chaotic consequences in expanding the race box hurt the scientific accuracy of data and sometimes even the social welfare, should we eventually abandon the race box or find a better alternative?

Finding Solutions

Katherine Wallman, who was the chief statistician of the United States from 1992 to 2017, said that to decide whether to have the race box in the future, we need to think critically about why we have it now. “It’s not because the Census Bureau is just nuts about wanting to know about people’s privacy. The Census Bureau and the government, in general, are collecting data on this because we have a bunch of laws in this country.”

The legal origin of the census and racial statistics can be found in our Constitution. Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution empowers Congress to carry out the census. The U.S. Census was the first in history to not only be used for taxation and military service but also be used for representation in Congress. In 1954, Congress certified earlier census acts and codified the decennial census as Title 13, U.S. Code. Title 13 reaffirmed the role of the census but didn’t specify the scope of subjects or questions in the census. Yet, the courts have held that the Constitution’s clause is not limited to a headcount of the population and does not prohibit the gathering of other statistics.

For a long time, census data on race and origin have served important roles in enforcing civil rights protections in legal and political domains. For example, race and origin data are essential for discovering evidence of racial discrimination in voting, which is integral to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Race and origin data have also helped enforce fair housing laws such as the Fair Housing Act and Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, as well as combat discrimination in employment and public health.

“If we don’t have [race and origin data], what do we do about trying to find out whether, in fact, we are addressing those issues? Whether we are being successful, whether people are being fairly represented in voting, whether people are being discriminated against in police stops, whether they are getting the education, regardless of their heritages, whether people are getting access to the vaccines?”, said Wallman.

From Woman’s perspective, the race box needs to stay in the U.S. census to reflect the racial disparities and the Census Bureau has been working hard to solve the concerns associated with the terms.

Proposed 2020 Census Combined Race and Hispanic Origin Question. Photo by the U.S. Census Bureau.

In the Obama era, the Census Bureau began testing a question that combined the race and ethnicity questions into one and also included a write-in line where more detail could be provided. The pilot study has shown the new form would encourage more census participants to provide data and improve data accuracy. Specifically, the combined question yielded higher response rates than the two-part question on the 2010 census form, decreased the “other race” responses without decreasing the proportion of people who checked non-white race or Hispanic origin.

However, a combined race and ethnicity question was not adopted in the 2020 census, despite the fact that the evidence showed that it was the optimal design to improve race and ethnicity data.

Adding a question to the census is never a unilateral decision, said Nicholas Jones, the director and senior advisor for race ethnicity research and Outreach in the census bureau’s population division. Besides empirical research and outreach with stakeholders, the new content has to be approved by the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the United States Congress. The 1997 OMB standards require that two separate questions have to be used for collecting data on race and ethnicity. The rule hasn’t been changed by OMB, so the Census Bureau’s hands are tied, said Jones.

The 1997 OMB standards lay out the foundation for the race box on the census form. OMB requires the five minimum reporting race categories (White, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander) and two minimum categories for ethnicity categories (Hispanic or Latino and not Hispanic or Latino). In 2014, OMB initiated a review process to consider changes to the 1997 standards. OMB convened an Interagency Working Group to review analysis conducted by the Census Bureau. However, the review process appeared to become dormant in 2017. No formal statement or explanation was given until the Census Bureau made an announcement in 2018 that it would not be using the combined questionnaire.

Even though a combined question was not adopted, the 2020 census made some other modest changes to strike a better balance between inclusivity and clearness.

First, a write-in area was provided for both White and Black or African American racial categories. For census takers, they can now choose to report their detailed background such as Irish or Jamaican. There were also more detailed checkboxes for Asian, American Indian or Alaskan native, and Pacific Islanders.

Second, the Census Bureau aggregated the data for quality control after the census data were collected and tabulated. For example, some respondents may report multiple ethnicities as Cuban and Salvadoran. Those detailed Hispanic responses will be collected but only a single Hispanic response will be tabulated. In terms of the detailed responses under the “other” category, those “other race” responses will be edited to match the relevant race category. For instance, a response of Iranian is coded under White, and Sudanese is coded under Black. In this case, people are allowed to use their self-identified terms and the answers would be regrouped based on the needs of data analysis.

The backstage processing of data sounds ideal: it provides the agencies with the flexibility of data analysis without sacrificing the wholeness of data entries. But from the perspective of efficiency, Wallman conveyed her reservations about how this solution may not work. Facing the complicated data breakdowns provided by the Census Bureau, state and federal agencies may not be able to make concrete decisions about what’s going on. More often than not, they chose to simplify the issues, said Wallman.

“I was somewhat surprised in my role to learn that places like the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission, for example, often put together all the nonwhite responses when they are looking at employment problems. They just looked at white versus nonwhite,” said Wallman.

In the scenario of multiple Hispanic or Latino national origins or subgroups, even the Census Bureau does not expect to report on the individualized answers. Specifically, if respondents indicated more than one Hispanic national origin subgroup, the Bureau would choose one Hispanic origin to use in reporting the aggregated data.

The complexity of designing a satisfactory race box aside, the lack of transparency in OMB’s efforts to find better solutions is baffling. It’s far from clear why the OMB and the Census Bureau dropped the combined racial and ethnicity categories, despite years and resources showing the good performance of the recommendations. The OMB and the Bureau should communicate the results of testing more clearly to the census takers and agencies, which has always been the key to solving confusion over the racial and ethnic questions.

In terms of the fear among racial minorities, the Census Bureau has coordinated active outreach to make sure people understand the census questions. Like what Martinez and his team have done in California Central Valley, many outreach programs across the country tried to broadcast the idea that although census could be confusing and scary for a new immigrant to the U.S., it’s nevertheless vital for civil rights.

“I think that a more inclusive process can certainly be established,” said Martinez. “But it has to be reconceptualized.” But how exactly should we reconceptualize the racial categories? One way to do so is by looking at how other countries have defined the terms of racial identities.

France: Racial Nationalism

Photo from French Today.

In France, racial identities are muted under the influence of French universalism. The universalist idea originated from the Enlightenment and the Revolution, where equality and liberty were upheld. French law prohibits asking a race, ethnic, religious, or language question on its census. The only permissible division on the census is between the nationals and the resident foreigners.

The idea behind racial nationalism is somewhat radical but has empirical appealing: we should abandon the race category in the census so that we will have less confusion caused by ambiguous terms and a less divided country split by racial differences. In a recent report by Heritage Foundation, authors argued that by emphasizing citizenship instead of race or ethnicity, the U.S. government can foster a sense of belongingness among immigrants and their children. There won’t be any need to defy the standard race category because citizens are united by their “common blood and inherited fitness as Americans.”

Many European countries share the idea of prioritizing nationality over race. In 2010, political elites of several European countries accused multiculturalism of encouraging the rise of home-grown terrorism. Specifically, they believed that the governments should foster a strong national identity, instead of encouraging diversity in racial identities. Few people in European nations said growing diversity made their country a better place to live, according to a survey by Pew Research Center in 2016. Even in the top three countries that relatively viewed diversity favorably, only about a third of people supported the idea of increasing racial diversity.

In 1860, nationality and the country of birth were first used to distinguish foreigners from Frenchmen, as well as immigrants from natives, in the census. The law of 7 February 1851 introduced a famous article under which French nationality was awarded automatically for third generations whose parents were born in France. In 1889, the law extended the possibility of naturalization to the second generation who were born in France.

The reforms of French nationality law took place when migration flows to France increased. 38% of 1,200,000 foreigners were born in France, according to the 1886 census. For parliamentarians, the rapid growth of the foreign population was seen as a great opportunity to strengthen the assimilation to citizenship. The 7-year compulsory military service after the acquisition of nationality further incentivized parliamentarians to relax the naturalization procedures.

Between 1871 and 1946, three categories were used to record nationality and remained unchanged: French by birth, French by naturalization (or by assimilation), and foreigner.

In the 1946 census, the data started to include those collected from France’s colonial empire. Little attention was paid to the foreigners and naturalized during the postwar period, except that Algerian Muslims were added to the nationality categories in the 1954 census.

In response to the fights for decolonization in Indochina and Algeria, the French census officials started to be more sensitive about the line between foreigners and citizens. In the 1968 census, more specific sections were used in the census to record the nationality and origin of foreigners. At the same time, Immigration policy in France also shifted from encouraging permanent immigration in the immediate postwar period to deterring migration after 1973, which marked a turning point in French immigration policy—from integration (every culture as equals) to assimilation (French culture comes first).

French’s policy of assimilation is closely linked to the core of French universalism. Although both France and America are lands of immigrants, French universalism is about how to eradicate the culture of the other and form the culture of the “I.” The shift of the policy from integration to assimilation stresses the idea of excluding otherness, which was provoked by the appearance of a “new immigrant.”

New immigrants are defined as ones who claim French citizenship but refuse to renounce their cultural heritages. In 1989, three girls of Muslim origin insisted on wearing the traditional scarf within the republican school. In this case, the French Universalism was seen as being challenged by rich and complex cultures like Islam that used to be regarded as otherness. The protest on acknowledging cultural heritages was in contrast with French universalism that was formed in the 18th- and 19th- century when immigrants were prone to “Frenchness” themselves.

Debates about ethnicity versus nationality then started. The resistance from nationalists towards multiculturalism was well captured by the demographer George Mauco’s comments on the otherness:

“[Asians, Africans, even Orientals] whose assimilation is not possible and, moreover, very often physically and morally undesirable…These immigrants carry in their customs, in their turn of mind, tastes, passions, and the weight of century-long habits that contradict the deep orientation of our civilization.”

However, things started to change in 1999 when a violent controversy on ethnic statistics erupted. There were rumors about introducing ethnic categories in the census questionnaires. While some researchers, who were called “taboo breakers”, supported denouncing nationality categories in the census only, some researchers kept promoting the narrative of color blindness and French universalism. The debates got highly personal when two researchers from the same institution even fought with each other on the issue.

The sphere of the debate, soon, expanded from scientific and technical to political, when discrimination became a more prominent political issue in 2004. The debate about whether to use racial statistics came down to this: whether ethno-racial categorization would only increase inter-ethnic confrontations, or was actually the key to address systemic discrimination in France.

Given the fact that France is still not receptive to ethno-racial categorization, will it provide empirical support for abandoning the race box to decrease confrontations among ethnicities? In other words, has the color-blind statistics achieved its anti-discrimination goal?

Not really. France’s non-European immigrants and their children were treated differently from those of European descent: Islamic immigrants, for instance, were discriminated against because of the belief that they were more likely to be criminals, and take jobs away from French workers. Even without racial census statistics, recent research showed that unemployment rates are higher for young immigrants compared to their “French-born” peers. Besides discrimination at the workplace, Black and North African youths were more likely to be stopped and searched by police, as studies about policing in France found out.

That being said, French officials are not blind to discrimination and there’s a vast quantity of anti-discrimination laws. Discrimination in employment, for example, is a criminal act, but without statistics to prove racial intent, it’s difficult to effect meaningful and lasting change. The reality is stark: the anti-discrimination law only worked on an individual basis, which made it largely ineffective.

COVID-19 heightened the absurdity of enforcing the anti-discrimination policy without data support. To better handle the pandemic situation, medical researchers agreed that it’s important to target vulnerable populations. While research in many other countries showed a higher death rate among non-white populations, French officials failed to observe the trend due to the lack of racial statistics. In one of the poorest regions in France, the contrast of COVID death rates among the different racial-ethnic groups was shocking: deaths among French-born was doubled, while they tripled among those born in north Africa and quadrupled among those from Sub-Saharan Africa.

However, despite the advocacy on better statistics, as well as evidence of racial disparity, the racial statistics may still not have a place in the French political agenda. In 2018, MPs voted unanimously to remove the word “race” from the French constitution. “Race” was deemed as an outdated term and “badly understood,” parliamentary groups said. In fact, they supported their conclusion by citing modern science which has shown that human beings do not belong to different, biological races. Even facing the COVID-19 challenge posed by missing ethnic data, President Emmanuel Macron’s office made it clear that “this is not a debate that the president wishes to open at this stage.”

The French approach to replacing race with nationality seems to be no longer feasible in a world where multiculturalism is in trend. Living in a society where racial differences are so-called assimilated, individuals in France still can’t avoid facing disparities in the economy, health, and education domains. From France’s example about erasing racial identities, we know that less is not necessarily better. But would it be the more the better?

Brazil: Racial Democracy

Photo from CNN

On a scale from 0 to 1, if France is close to 0 in terms of celebrating racial-cultural diversity, then Brazil is near 1.

The racial narrative in the Brazilian census is different in two ways: it does not place an emphasis on nationality (unlike that in France), but at the same time, it discards common distinctions like race and ethnicity (unlike that in the U.S.). Instead, Brazilians are counted by color, which has referred to physical appearance, not racial origins. In the early 19th-century Brazilian censuses, four categories—white(Branco), black(preto), brown or mixed(pardo), caboclo (mestizo Indian)—were used. The colors white, black, brown, and yellow soon became the official lines distinguishing census takers.

Brazil has a colonial past in which indigenous Indian populations were marginalized by Europeans and African slaves were imported. However, after the legislation passed in 1871 to abolish slavery, interracial marriage was more actively encouraged, resulting in a mixed-race population of about 40 percent reported in Brazil’s recent census. The term, racial democracy, was coined to mark the racial dynamic in Brazil where various races lived as equals. Racial democracy in Brazil is different from racial nationalism in France: the former was more based on the biological grounds that people share similar heritages, while the latter focused on voluntary assimilation among the immigrants.

The unique racial mixture reinforced the nondiscriminatory image of Brazilian society: there can be no racial discrimination because Brazilians are racially mixed, as Melissa Nobles pointed out in her comparative analysis of racial/color categorization in U.S. and Brazilian Censuses.

With the growth of mixed-racial populations, it’s natural to think if racial democracy is our future as well. While color and race are used interchangeably in the states, color, in the context of racial mixture, focuses more on the present than the past. If almost half of the population are racially mixed, the logic is that it doesn’t matter (and impossible) to classify people based on few racial origins. Shades of color thus are more accurate labels. In fact, in many Brazilian families, different racial terms are used to refer to different children.

However, the racial mixture could get messy when it made racial categories imprecise.

In 1970, a study conducted by Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), the counterpart of the Census Bureau in Brazil, reported that they received 135 different answers when asked people to report their color. Another 2009 study by researchers from Brazil found that among the students they sampled, people reported 18 different terms of their color and the use of terms varied greatly depending on the context. 20% of the students “changed” their color 4 months apart.

Besides the lack of consistency, the imprecision is also caused by the ambiguity of terms in the questions. Pardo, for example, was defined as both “gray” and “brown” in Portuguese-language dictionaries. The word “Pardo” was also rarely used in any other common exchanges beyond census. Preto, which means black in census terms, has also been more often used to describe objects instead of human beings. Thus, census takers may treat the census terms indicating colors differently based on their own interpretation of the meaning of words.

But the problem with terms could be fixed when the administration aggregated similar color tones, which is easier considering the proximity among answers. Moreover, the significant impact of allowing more racial categories in Brazil proves the benefits of racial democracy.

Many studies in recent years have found that most focus groups produced a collective social knowledge of genetics and race. Specifically, in a society like Brazil where people are exposed to the image of racial mixture, people do not passively accept the genomic information but chose to embrace the self-categorization of ancestry, especially when the scientific results contradicted their notions. People were more receptive to racial differences and engaged in the correction and augmentation of racial inequalities.

The positive results of racial democracy in Brazil provide insight for the design of racial categories in the U.S. census: the controversies about the race box might be solved by expanding racial categories instead of abandoning them. More importantly, self-identification should be highly encouraged because it not only promotes people’s understanding of race and ethnicity but also eventually bridges the gap among racial differences when a new nationality is formed—we are who we are not because of our ancestry but our current and continuing efforts to break barriers.

“To change the world, one has to change the ways of world-making, that is … the practical operations by groups were produced and reproduced,” said Pierre Bourdieu, an influential French sociologist. To solve the crisis at the race box in the U.S. census, it’s time to make the racial narratives more inclusive, as the imprecision might not be an issue anymore when racial democracy is achieved.