Abstract

During a period of democratic backsliding and increased weaponization of the internet by governments, privacy and censorship circumvention software has become all the more vital in preserving fundamental human rights and protecting vulnerable communities. Edward Snowden, the American whistleblower responsible for revealing the now-illegal NSA phone records collection program, ended his memoir, “In a perfect world, which is to say in a world that does not exist, just laws would make these tools [like SecureDrop] obsolete. But in the only world we have, they have never been more necessary. … In my current situation, I’m constantly reminded of the fact that the law is country-specific, whereas technology is not.”[1] As Tor becomes a haven for anyone seeking privacy, it is important to understand how users are accessing the software and when citizens are most likely to turn to it. Using datasets compiled from the EIU’s Democracy Index reports, GDELT 2.0, and social media platforms’ transparency reports, this paper seeks to provide some answers to the question, how might different types of world events affect the use of Tor?

1. Introduction

In 2020, the world received the worst score for democratic practices since the Economist Intelligence Unit began evaluating such measures in 2006.[2] 70% of countries worldwide saw their scores decline as standards of civil liberties, functioning of government, political culture, electoral process and pluralism, and political participation plummeted.[3]

The internet, in particular, has become a battleground for democracy as government surveillance and censorship increases, citizens turn to social media to get their voice out, and “big tech” falls in the middle – subverting governments’ increased presence while also looking to collect citizens’ data. In February 2021, the Indian government and Twitter went head-to-head, ending with the government threatening to arrest any Twitter employees who refused to block activists tweeting their support for the Farmers’ Protest.[4] In May 2021, they passed laws forcing all technology companies to fulfill government requests to remove content within three days and comply with all law enforcement requests for information on citizens. The executive director of India’s Internet Freedom Foundation, Apar Gupta, declared the Indian government’s actions were the kind that heavily regulate “areas that enrich any kind of democracy,” encouraging self-censorship.[5]

The February debates began the same month the world’s longest internet shutdown technically ended. In June 2019, former leader and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi shut down the internet of Rakhine, Myanmar. The state would go on to live in the digital dark for roughly 19 months before a military coup prompted a brief respite.[6] Days later, however, the same military junta in charge of the coup shut the internet back down, beginning an ongoing period of internet instability. Citizens have counteracted these shutdowns to the best of their ability through physical internet hookups and messaging apps that employ “proximity-based Bluetooth mesh networks” to connect.[7] When finally connected to the internet, be it through a physical hookup or the brief periods of state-enabled activity, software such as the Tor Browser and VPNs have been used to get around the walls of government censorship and protect vulnerable citizens’ identities.[8]

The Tor Project, the nonprofit behind the aforementioned Tor Browser, has been working to implement free speech, information, expression, and media tools in every country since 2006, when they were founded, acknowledging these freedoms’ significance to democracy. The early software structures were developed in 1995 by the United States Naval Research Lab. They intended to produce a secure communication channel for the Navy and allied countries, preferably through the dark web, any part of the internet inaccessible without special software. The current name, “Tor” is short for “The Onion Router,” a reference to the dark web’s practically impenetrable structure of anonymity made possible through “onion routing,” the layers upon layers of servers and encryption a user’s activity goes through when using the software.[9] It was bestowed upon the later onion routing project by co-founder Roger Dingledine. Along with Paul Syverson from the Naval Research Lab and fellow MIT alum Nick Mathewson, he would publish the first open software license for Tor in October 2002. The network they created allowed others to host nodes; the more nodes, the more servers traffic could go through, and the more anonymous one user’s data would be.[10]

Since then, its popularity has only grown, not just in the United States but worldwide, due to the 2008 development of the Tor Browser and the unmatched level of privacy the software provides its users.[11] As such, it has been adopted by numerous activist groups, journalists, and the like to circumvent laws set out to oppress speech and hide information from the public. On Tor, users may communicate, look up current events, ask questions, and speak to journalists with less fear of government retaliation. Tor also circumvents large-scale blocking structures, like the Great Firewall, so that users may access dissident information, such as banned books and political forums.

The Tor Project illustrates five “Personas” on their website: Jelani, Aleisha, Fernanda, Fatima, and Alex. Each Persona represents patterns in user experience that emerged from a series of international interviews the nonprofit conducted in 2018 and 2019.[12] Jelani is an LGBTQ+ activist from Uganda who is at high risk for government persecution due to his sexuality and activism and struggles with government-inflicted power outages and bandwidth throttling. Aleisha is a survivor of domestic abuse living in Russia. However, due to the government’s prohibition of VPNs and blocking public relays, she has trouble learning how to use Tor. Fernanda is a women’s rights activist from Colombia who is confident in her ability to use Tor and will set up an onion service for her reproductive rights collective, who would otherwise be prosecuted for their work. Fatima is a political researcher from Egypt at significant risk, who must use a bridge to connect to Tor due to the heavy censorship in her region. Alex is a journalist from the United States who uses Tor to communicate with their sources since those who report on subjects like state surveillance and immigration, as they do, are under scrutiny from the government.[13]

The Tor Project created these Personas to lead “human-centered design processes.”[14] For the public, they illustrate five very real scenarios in which Tor can help one maintain anonymity and access to information while using the internet. However, these are not the only times people turn to Tor. During the annual 2020 State of the Onion conference, Antonela Debiasi, the Tor Project’s UX Team Lead, emphasized that the Tor Browser is a “critical tool for this time of evolving democracies.”[15] At the same conference, Nathan Freitas from The Guardian Project noted that as Tor has increased in popularity, censorship of the network has also increased, making projects like the pluggable transport Snowflake all the more valuable.[16] As Tor becomes a haven for anyone seeking privacy, it is important to understand how users are accessing the software and when citizens are most likely to turn to it. Using datasets compiled from the EIU’s Democracy Index reports, GDELT 2.0, and social media platforms’ transparency reports, this paper seeks to provide some answers to the question, how might different types of world events affect the use of Tor?

2. Related Work

Research on Tor typically falls into one of three categories: those who seek to uncover the “scary world” of darknet markets, those conducting technical research hoping to improve things on the back end, and those who analyze its use in a political context, often centering on issues of privacy and censorship. This paper very much follows the last category. As Joss Wright et al. argue in “On Identifying Anomalies in Tor Usage”: “The use of Tor metrics data, amongst other sources, is of use not only as an indicator of its own usage patterns, but as a practical proxy variable for a much wider class of political and social events.”[17] A brief review of the current research done on Tor in a political context will follow. For ease of reference, this review is broken into two subsections: government censorship and surveillance and the benefits of and debate surrounding Tor.

2.1 Government Censorship and Surveillance

A 2020 case study of Russia by Reethika Ramesh et al. laid out the three main censorship methods governments use to restrict their citizens’ access to certain websites or categories of websites. The most disruptive method is TCP/IP blocking, where full IP addresses are blacklisted, preventing citizens from accessing the prohibited site and preventing them from reaching any other website hosted at the same IP address. This is how China can block Tor proxies. The method that allows for the best “fine-grained filtering” is DNS manipulation, which allows specific hostnames to be pinpointed and blocked, rerouting the user to an error page. The third method, keyword-based blocking, is the most resource-intensive for governments. In this instance, a block page is triggered when the sensor detects a keyword in the HTTP(S) corresponding to a country’s blocklist.[18] Russia specifically was chosen for analysis in their paper as its censorship method is decentralized; it is the responsibility of the ISPs to ensure the correct content is censored. Ramesh et al. note that the U.S. and U.K. employ similar methods, and while they do not restrict as much information as Russia, “the option to follow the same path is cheap, readily accessible.”[19] Many countries have their blocklists, but few are ever purposefully made public. Russia, for example, maintains a “Registry of Banned Sites,” and Syria allegedly blocks “every website with a .il (Israel) domain name.”[20] In addition to these blocklists, another type of list, the “pinklist,” was recognized in the 2017 study, “Topics of Controversy: An Empirical Analysis of Web Censorship Lists”: Zachary Weinberg et al. define pinklists as any blocklist that primarily features pornographic websites. Regardless of the type of website, however, Weinberg et al. found that any website on a pinklist was more likely to be shut down than a website on another type of list.[21]

Ironically, a 2018 study by William Hobbs and Margaret Roberts found that government censorship can end up increasing citizens’ access to the information their government wishes to prohibit.[22] As circumvention tools are not designed with one country in mind, their discovery and use create a “gateway effect,” according to which users grow “accustomed to accessing the newly censored information.” This is seen in the phenomenon where the blocking of one apolitical platform, like Instagram, led to users joining other platforms better known for engaging in political debates, like Twitter and Facebook.[23] Hobbs and Roberts specifically revealed that on the day of China’s 2014 Instagram block, the rate of new Twitter user account creation “jumped more than 600%.”[24] As users are incentivized to find censorship circumvention methods to access their favorite platforms or substitutes, they are exposed to a vast, varied amount of content that can reveal even more information against the government than they had access to before.

The debate over anonymity has become as great as that over the direct censorship methods outlined above. The desired scope of anonymity can vary considerably between people depending on the actions they plan to take, the laws of their country, and their identity. Anand Raje and Sushanta Sinha’s overview of anonymous traffic networks calls out two types of anonymity: technical, “the removal of all meaning identifying information about others in the exchange of material,” and social, “the perception of others and/or oneself as unidentifiable because of a lack of cues to use to attribute an identity to that individual.”[25] Thorsten Thiel in “Anonymity – The Politicization of a Concept,” dives deeper into this concept of social anonymity and how it plays out under a surveilled internet. He notes a few trends regarding how anonymity has been portrayed in the past decade: anonymity as a “form of justified civilian defense” against data collection, a benefit that allows for more personalized services, an “obstacle to the application of the law” by law enforcement, a danger to those who enforce copyright, and a safe method of communication.[26]

These debates surrounding the right to anonymity on the internet are often connected to issues of social justice. Randall Amster, in “Mapping Digital Justice,” emphasizes the disproportional impact surveillance has on vulnerable communities: “In this emerging brave new world in which ‘the future of justice is digital,’ vulnerable populations can be doubly punished by having less access to the benefits of technology while bearing disparate burdens based on preexisting inequalities.”[27] Amster quotes researcher Malkia Cyril’s concept of the “digital sanctuary,” a term derived from “sanctuary cities.” A “digital sanctuary” is a digital environment made up of “tech policies, platforms, and practices” that provides equal protection and nearly total anonymity to every user.[28]

Human rights defenders are often amongst those communities most vulnerable to government persecution as they frequently work in active opposition to those in power. Australia-based NGO Oxen Privacy Tech Foundation published a report on March 5, 2021, titled, “Ground Safe: Assessing the digital security needs and practices of human rights defenders in Africa, MENA, South Asia, and Southeast Asia.” Through interviews, the report detailed the most meaningful ways governments are targeting human rights defenders through technology, including personal, reputational, legal, and infrastructure attacks.[29] Those categorized as “personal” involve social media surveillance and online threats that can turn into physical attacks on the defender and their families. Reputational primarily involves severe cases of disinformation portraying the defenders and their organizations in negative ways. While legal cases also involve social media surveillance, with defenders’ dissident posts leading to their arrest, it additionally details situations where social media apps are “hijacked and taken over by unknown individuals” who purposefully share illegal content to get the defender arrested under cyber laws.[30] Infrastructure concerns revolve around compromised devices with unintentionally installed malware and internet blackouts, such as the case in Myanmar.[31]

2.2 The Benefits of and Debate Surrounding Tor

Ben Collier begins his paper, “The Power to Structure: Exploring Social Worlds of Privacy, Technology, and Power in the Tor Project,” affirming the vital role of privacy in the structure of liberal democracies’ governments.[32] Andrew Lindner and Tongtian Xiao, in “Subverting Surveillance or Accessing the Dark Web?” recognize the “central concern of many civil liberties advocates is that a growing surveillance state may deter perfectly legal forms of behavior, thought, and expression due to fear of exposure.” They attribute the growth of Internet surveillance to two factors: the mass surveillance programs following the declaration of the War on Terror and the far-reaching development of social media platforms whose primary purpose is to allow users to share their data.[33] Together, they created a perfect storm and led to the need for Tor. “From the activist perspective,” Collier writes, “Tor is inherently political, promoting values of liberation and democracy.”[34]

Some wonder whether Tor provides its users with too much privacy, unintentionally encouraging illegal activity. This is why some activists resist the phrase “dark web,” as it conjures images of drug deals and contract killings. Brady Lund and Matt Beckstrom try to undercut this negative depiction of Tor in their 2021 paper, “Integration of Tor into Library Services.” They point out that not only do “Wild West” sensationalistic stories of the dark web “sell big,” and that “Illegal content exists everywhere on the Internet.”[35] The important element is how one uses the web. “Tor was not designed for crime, just as the Internet in general was not.”[36] Lindner and Xiao sought to provide evidence for this idea in their 2020 study analyzing the effect specific Tor-centered articles had on Google search trends for Tor. They believed this would reveal the general population’s motives for using the software. They found that these sensationalist stories of dark web crime were not significantly associated with interest in Tor.[37] Rather, they expanded on Marthews and Tucker’s work,[38] which saw Google searches on “personally and politically sensitive topics” decline after Snowden’s whistleblowing in 2013 and discovered that interest in Tor was positively correlated with interest in Snowden. For every 10% increase in Snowden-related searches, there was a 7.4% increase in searches for Tor.[39]

Other privacy developers see the illegal activity as an indicator of Tor’s safety – if a criminal feels safe, so should an activist. In Weaving the Dark Web, Robert Gehl quotes network builders as saying, “One person’s terrorists and anarchists…is another’s freedom fighters and revolutionaries – that is, dissidents.”[40] If governments around the world were able to de-anonymize every individual they deemed a criminal, the lives of journalists and activists would be at significant risk. Programs like SecureDrop enable journalists and their whistleblower sources to pass information to publications like ProPublica and the New York Times. Rob Jansen, Justin Tracey, and Ian Goldberg acknowledge in “Once are Never Enough” that adversaries are so threatened by the secure communication Tor provides that they go so far as to “intentionally degrade usability to cause users to switch to less secure platforms.”[41] This fact underlines once more the importance of research in this space. If the Tor Project can predict when there may be an influx of users or increase interest in the software, they can better direct their efforts to that area. Often, the countries that need Tor the most are most riddled with the government censorship and surveillance described above. This means the Tor Project will need to keep an eye out for newly blocked Bridges, provide extra support to these new users who likely do not have access to the same educational resources, respond to special BridgeDB requests, and carefully watch the performance of Snowflake, their newest tool for heavily censored countries.

3. Data Curation

Ten datasets were downloaded for this paper. Each had a different schema which was edited so the Country and Year values would align and could be merged when needed. The spelling of each country was standardized[42] using the “Common” name listed in the Countries GitHub repository, which lists variations of country names based on the ISO Standard 3166-1.[43] Years were parsed from dates when needed. In addition to Year and Country, three key columns were added to ensure the uniformity of names: Region, ISOAlpha2, and ISOAlpha3. Regions were assigned according to the United Nations list of intermediate subregions. ISOAlpha2 and ISOAlpha3 represented ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 and ISO 3166-1 alpha-3. All data was cleaned in R[44] except for GDELT, which was queried and cleaned through Google’s BigQuery and Data Studio.

3.1 Tor Metrics

The dataset of Tor Metrics was compiled through R.[45] All metrics are publicly available through the Tor Project’s website.[46] A simple Python code automated the process of downloading the individual countries’ datasets. These sets included the number of Relay connections[47] and the number of Bridge connections[48] per day for the date range January 1, 2016, through December 31, 2020. They are processed anonymously by Tor, allowing the public to download aggregated versions for observation.

3.2 Democracy Index Reports

The second dataset contained the Economist Intelligence Unit Democracy Index reports from 2016[49] through 2020.[50] While the Economist Intelligence Unit provides CSVs for only a few years, Gapminder compiled every year’s data since 2006 into one CSV.[51] This sheet was cleaned and organized as described above through R to better work alongside the Tor Metrics and other datasets.

3.3 Transparency Reports

Apple,[52] Twitter,[53] and Facebook’s transparency reports[54] acted as the third through fifth datasets. Reports from 2016 through 2020, each year, are broken into two periods, were downloaded. They were all downloaded from their respective websites and cleaned through R. Facebook changed the user interface of their transparency report section on April 28, 2021, so it is now more accessible for the general public to browse the data through their website.[55]

3.4 Internet Technology

The Huawei Global Connectivity Index (GCI) reports for 2016 through 2020 were downloaded through Huawei’s website and cleaned in R.[56] Likewise, the dataset of Secure Internet Servers per One Million People for 2016 through 2020 was downloaded through World Bank and cleaned in R.[57]

3.5 GDELT 2.0

The most massive database by far was the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT).[58] This database scans news stories every day and reports back a wide variety of factors, including but not limited to the actors involved – their religion, nationality, known group affiliations, types – and details about the event the story describes – location, type, and state response. It is also host to numerous other databases, including the Global Knowledge Graph (GKG) that analyzes factors, such as the tone of events, and the Visual Knowledge Graph (VGKG), which analyzes photos for certain identifying details. All databases can be viewed through the website, downloaded in raw files, and queried through Google BigQuery. The latter was employed for this paper as it allowed for the most extensive dataset download, accounting for storage and program abilities. From the most updated version of GDELT, GDLET 2.0, data was queried to include every instance registered by the database between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2020, that listed a country code for at least one actor, a country code for the location of the event, at least one type code for at least one actor, and a type code for the event itself. Country is coded according to the ISO 3166-1 Alpha-2 format, and event and actor codes are based on the Conflict and Mediation Event Observations (CAMEO) codebook.[59] This data was cleaned through BigQuery, Google Data Studio, and Tableau.

4. Analytical Methodology

Compiled, the data for this paper included approximately 1.4 million observations. ANOVA and t-tests were performed through Tableau to test the significance of and correlation between Tor use and the different datasets described above. The corresponding graphs were also simultaneously created in Tableau.

4.1 Internet Technology

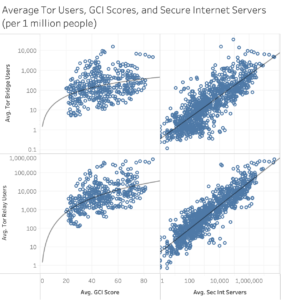

The first tests performed looked at countries’ Global Connectivity Index scores and the number of Secure Internet Servers per one million people they have.[60] The Global Connectivity Index measures forty indicators of countries’ Information and Communication Technology based on four pillars: supply, demand, experience, and potential. The variables underneath the four pillars are further broken down into five categories: fundamentals, broadband, cloud, internet of things, and artificial intelligence.[61] Secure Internet Servers are included within the Global Connectivity Index under the Demand pillar and Fundamentals category. However, it was separately analyzed, using NetCraft’s count, to account for variances in internet specifically, as there was no consistent annual data for internet users per country. These four ANOVA tests, GCI and Relay Users, GCI and Bridge Users, Secure Internet Servers and Relay Users, and Secure Internet Servers and Bridges Users, were performed first so the other categories could be compared to the general correlations between internet technology and Tor use.

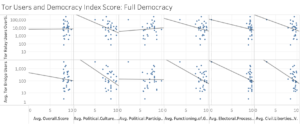

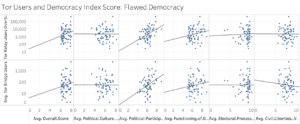

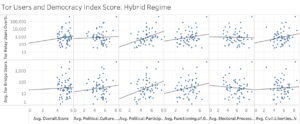

4.2 Democracy Index Reports

Next, ANOVA tests were performed to analyze the significance and correlation between Tor use, divided into Relay and Bridge users, and the five indicators of democracy as defined in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) annual Democracy Index Report. Analysis was done on all countries collectively[62] before separating them into government types, also specified in the EIU’s report. In an EIU report, each country is given an overall score, the Democracy Index, which averages their scores in each of the five indicator categories: Civil Liberties, Electoral Process and Pluralism, Functioning of Government, Political Culture, and Political Participation. The Democracy Index score defines their government type; a score under 4.00 indicates an Authoritarian Regime,[63] 4.01-6.00, a Hybrid Regime,[64] 6.01-8.00, a Flawed Democracy,[65] and 8.01-10.00, a Full Democracy.[66] For the Index, the EIU defines all terms with the goal of democracy in mind. Therefore, the electoral process and pluralism score looks at how free and fair a country’s elections are and viable opponents in the elections. The functioning of government score assesses how well elected politicians take citizens’ wishes into account during policymaking. Political participation summarizes how involved citizens are and laws around their participation in the political process. Political culture includes how strongly the public believes in a democratic system and if political freedom and separation of church and state are honored. Lastly, civil liberties encompass all fundamental human rights, including freedoms of speech, religion, expression, the press, and the right to a fair trial. There has been a negative trend in the global average score in recent years as countries move further from a “Full Democracy” classification. 2016’s score, 5.52,[67] was a fall from 2015’s 5.55 global average.[68] 2017’s score was lower than 2016 at 5.48,[69] though it stayed the same through 2018.[70] In 2019, the score fell again to 5.44, a record low since the EIU began publishing the Democracy Index in 2006.[71] In 2020, a score of 5.37 was reported, setting yet another new record low.[72] Now, 35.6% of the world’s population lives under an authoritarian regime, and only 8.4% live in a full democracy.[73]

4.3 GDELT 2.0

In order to further break down the relationship between Tor use, government structure, and political events, the relationship between Tor use and different categories of world events was analyzed. Event data was retrieved from and categorized by the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT) database. ANOVA tests were performed on the Tor metrics, again divided between Bridge and Relay users, and the variable “EventCodes,” revealing the type of event that occurred.[74] There are 20 base categories, each with a varying number of individual subcategories.[75] After performing an additional t-test for each base and subcategory, the number of subcategories significant at 1%, only significant at 5%, only significant at 10%, and only significant at levels higher than 10% were added up to get the total per base category. This was done in order to summarize the data and highlight the differences between each government type analyzed: Full Democracies,[76] Flawed Democracies,[77] Hybrid Regimes,[78] and Authoritarian Regimes.[79] The number of positive and negative correlation coefficients was added as well. As the number of subcategories varies per base category, another table was created assessing the proportion of events significant at 1%, only significant at 5%, only significant at 10%, and only significant at levels higher than 10%. Across all government types, the ranking of the different base categories, based on the number of subcategories significant at 1%, shifted in this table.[80]

4.4 Transparency Reports

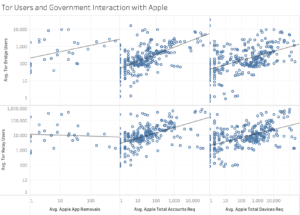

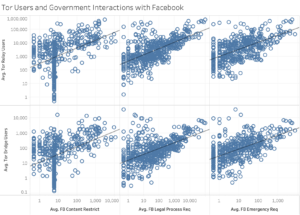

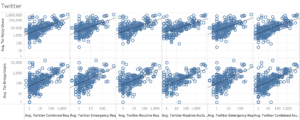

The last tests were a series of ANOVA tests performed to highlight the relationships between transparency reports from Apple, Facebook, Twitter, and Tor. For the tests concerning Apple’s reports, the categories Apps Removed by Government Request, Total Accounts Requested by Governments, and Total Devices from which Governments requested information were analyzed.[81] Three categories, Content Restricted by Government Request, Emergency Requests, and Legal Process Requests from Governments, were likewise analyzed from Facebook’s reports.[82] From Twitter’s reports, five categories were tested: Total Accounts Requested by Governments, Average Number of Government Requests, Emergency Requests, Total Routine Accounts Requested by Governments, and the Total Number of Government Routine Requests.[83] These tests were performed to understand better how government actions taken against popular platforms affect Tor use.

5. Results

In this section, the results most of interest from each set of tests will be summarized.

5.1 Global Connectivity Index and Secure Internet Servers

The Global Connectivity Index and the number of Secure Internet Servers showed significance at 1% for Relay and Bridge users. However, R-squared values for the Global Connectivity Index were low, with 0.1091 being recorded for Bridge users and 0.2993 being recorded for Relay users. Conversely, the r-squared values for Secure Internet Servers were relatively high at 0.6739 for Bridge users and 0.7950 for Relay users, revealing that the number of secure internet servers available does likely impact Tor use.[84]

5.2 Economist Intelligence Unit

Every category returned a p-value indicating a significance at the 1% level when assessing all countries together. As was the trend across every government type, the r-squared values did not indicate a solid relationship in explaining the variance in Tor use through the democracy indicators. However, as the p-values varied across types, these tests may illustrate some close connections between types and the indicators that show significance.[85]

Analysis of only Full Democracies returned the highest number of p-values indicating insignificance. None were significant at 1%, though Civil Liberties and Electoral Process and Pluralism for Bridge use showed significance at 2% and 3%, respectively. Political Participation for Bridge use showed significance at 5% and Functioning of Government showed significance at 7%.[86]

Flawed Democracies presented significance at 1% with their overall Democracy Index score for both Bridge and Relay used. Political Culture for Relay use also showed significance at 9%.[87]

Continuing a similar trend, Hybrid Regimes exhibited significance at 1% for their overall Democracy Index score for both Relay and Bridge users. However, no other indicator demonstrated was significant under 10%.[88]

Authoritarian Regimes presented significance at 1% for both Relay and Bridge users for Functioning of Government. Electoral Process and Pluralism were significant for Bridge users at 6%.[89]

As previously noted, the r-squared values across types were low. The highest r-square values were seen when aggregating all countries together. Even then, the highest value was 0.3141 in the Political Participation, Relay users category. This was followed by a value of 0.2776 in Electoral Process and Pluralism for Relay users and 0.2507 for Functioning of Government. The highest r-squared value was 0.1696 in Political Participation for Relay users in Flawed Democracies outside of the aggregated countries.[90]

5.3 GDELT

5.3.1 Significance Regardless of the type of governmental structure, it was found that the variable “EventCodes” had a p-value less than 0.00001, rejecting the null hypothesis, indicating that the relationship between the events logged by GDELT from 2016-2020 and Tor use is highly significant. Knowing this, ANOVA tests were performed on the individual categories and subcategories of events, as assigned by GDELT.[91]

While there were commonalities across the different government types, none shared the same ranking of base categories. When analyzing all countries aggregated, the base category “Yield” had the highest number of subcategories significant at 1%, 27. “Express Intent to Cooperate” was not much lower with 25. However, proportionally, “Consult” and “Provide Aid” were the highest, with 100% and 92% of their subcategories significant at 1%, respectively. “Investigate” had the second-lowest number of subcategories and was the lowest-ranked proportionally among the base categories.[92]

Unlike the numbers presented for all countries, Full Democracies saw “Yield” have the lower number of subcategories significant at 1%. “Fight” had the highest number with 6, and “Make Public Statement” had 5. Proportionally, “Fight” remained the highest, with 46% of its subcategories being significant at 1%. Like the aggregated countries, “Consult” was also amongst the highest proportionally with 29%. “Reject” and “Reduce Relations” were the two lowest.[93]

Flawed Democracies also saw “Consult” have the highest proportional number of subcategories significant at 1%. However, when counting the number of subcategories, “Make Public Statement” was ranked the highest with 18, followed by “Disapprove” with 15. “Use Unconventional Mass Violence” was the lowest both numbers-wise and assessed proportionally.[94]

Hybrid Regimes nearly matched Flawed Democracies; however, “Coerce” not “Disapprove” had the second-highest number of subcategories significant at 1%.[95]

Authoritarian Regimes saw “Disapprove” and “Make Public Statements” as the base categories having the highest number of subcategories significant at 1%, the former having 17 and the latter 16. “Use Unconventional Mass Violence” surprisingly had none, and “Demand” only had three. Interestingly, it was the only regime type that shared “Fight” with Full Democracies as one of the highest base categories when ranked proportionally, with 86% of its subcategories being significant at 1%. “Consult,” however, was the highest-ranked with 100%, while “Demand” and “Use Unconventional Mass Violence” remained the lowest.[96]

5.3.2 Coefficients and r-squared values The most noticeable difference between the different government types emerged when calculating the number of positive and negative coefficients under each type. For every type except Full Democracy, there were over 50% more positive coefficients than negative. Full Democracy, however, included 87 positive coefficients and 283 negative coefficients, indicating that Tor use in a Full Democracy is negatively correlated with the majority of events recorded by GDELT. In other words, people in Full Democracies are less likely to use Tor when these events occur.

Notably, the two events codes with positive coefficients that are significant at 1% and have the two highest r-squared values are 1382, “Threaten occupation” (Relay and Bridge) and 1411, “Demonstrate or rally for leadership change” (Relay). These are likely the two events that might occur before an increase in Tor use by those in Full Democracies.[97] The event with a negative coefficient, significant at 1%, and the highest r-squared is 184, “Use as human shield” (Relay). This entails any situation involving the use of “civilians as buffer on the front lines or in other dangerous environments.” However, it must be noted that the two events with positive coefficients described above have much higher r-squared values, 0.9997 (Relay), 0.9996 (Bridge), and 0.4838, than the latter, 0.3767. While most coefficients in Full Democracies appear to be negative, the majority of those with high r-squared values, indicating a stronger relationship between the independent and dependent variables, have positive coefficients.[98]

In Flawed Democracies, the two events with positive coefficients, significant at 1%, that have the highest r-squared values are 0244, “Appeal for change in institutions, regime” (Relay) and 0814, “Ease state of emergency or martial law” (Relay and Bridge). Conversely, 0834, “Accede to demands for change in institutions, regime” (Bridge), has the highest r-squared of those significant at 1% with a negative coefficient. However, this event only has an r-squared value of 0.0545, so while the demonstration of a positive relationship between the previous events and Tor is clear with r-squared values of 0.9893, 0.9858 (Relay), and 0.9360 (Bridge), there is not a strong indication that any of these events meaningfully negatively impact Tor use.[99]

038, “Express intent to accept mediation” (Relay) and 082, “Ease political dissent,” (Relay) are the events with positive coefficients, significant at 1%, that have the highest r-squared values for Hybrid Regimes, and 1042, “Demand policy change” (Bridge) is the event for the negative coefficients. It should be noted that in this case, the event with a negative coefficient has the more considerable r-squared value, though none are above 0.5.[100]

Looking at the same statistics, the events with positive coefficients for Authoritarian Regimes are 1211, “Reject economic cooperation” (Relay and Bridge) and “Refuse to ease economic sanctions, boycott, or embargo” (Relay). The events with negative coefficients are 1382, “Threaten occupation” (Relay), and 0255, “Appeal to allow international involvement (non-mediation)” (Relay). Here, it is important to note that the r-squared values across coefficients are high, with those with negative being very high at 0.9999 and 0.9998, respectively.[101]

5.4 Transparency Reports

All categories analyzed from Apple’s reports exhibited significance at 1% except for App Removal, Relay users, which had a p-value of 0.7046. It also had the lowest r-squared value out of the categories by far. The highest r-squared value was 0.3756 with Total Accounts, Bridge users.[102] Analysis of Facebook’s reports revealed that all categories exhibited significance at 1%. The highest r-squared value was 0.4056 with Legal Process Requests, Relay users, and the lowest was 0.1895 with Content Restricted, Relay users.[103] Like in the case of Facebook, all of the categories from Twitter’s report had p-values indicating significance at 1%. The highest r-squared value returned was 0.4127 with Total Accounts Requested, Relay users, and the lowest was 0.2790 with Emergency Requests, both Relay and Bridge users. Twitter’s categories had the highest average r-squared value at 0.3509, followed by Facebook’s with 0.2985 and Apple’s with 0.2199.[104]

6. Discussion

6.1 Global Democracy Index Reports

Eric Jardine published a study in 2016 that found citizens in countries with either very high or very low levels of oppression were more likely to use Tor than citizens afforded moderate levels of freedom.[105] The idea behind this theory is that under extremely high oppression, the risk citizens take in downloading the software is outweighed by the level of freedom they will gain if successful. Under very low oppression, citizens likely have no reason, legally, not to use it. The ANOVA tests performed on the Tor Metrics and Democracy Index Reports appear to be consistent with this idea. While, as noted before, the majority of the results were insignificant, the tests did give p-values for Flawed and Hybrid Regimes that revealed a significance at 1% in the overall Democracy Index Score category. As the two “middle” government types, it would make sense, alongside Jardine’s study, that the most significant relationship between Tor use and Flawed and Hybrid Regimes would be an overall increase or decrease in democracy. A slight fluctuation in a subcategory might leave them in the same “middle” type as before. Users are likely more motivated to use Tor when observing a fundamental shift in their country’s government type. The significance of Civil Liberties and Electoral Process and Pluralism categories under Full Democracies is interesting as elections, and free speech are two of the most commonly associated traits with democracy.

6.2 GDELT 2.0

The ANOVA and t-tests performed on the Tor Metrics, and events coded by GDELT reveal definite differences, as expected, between different government types. However, a few categories of events revealed opposite behavior to that predicted. Most apparent was that of “Use Unconventional Mass Violence.” While it was expected that the variable would be significant, with positive coefficients and high r-squared values, it was both the lowest counted and proportional event category in Flawed Democracies and Hybrid Regimes. Likewise, there were no counted events of this type that were significant at 1% in Authoritarian Regimes, and thus it was the lowest-ranked proportionally as well. The significant, negative coefficients for “Use as human shield” in Full Democracies and “Threaten occupation” in Authoritarian Regimes also were not in line with the expected outcomes.[106]

“Threaten occupation,” however, also illustrates one of the differences between regime types as it did present itself as imagined in Full Democracies. Within Full Democracies, “Threaten occupation” is significant at 1%, has a positive coefficient and extremely high r-squared values. This indicates that when there is a “threat to occupy or seize control of the whole or part of a territory,” users in Full Democracies are more likely to use Tor. The other similarly significant category, “Demonstrate or rally for leadership change,” follows predictions as well.[107]

Both Full Democracies and Authoritarian Regimes report “Fight” as having a proportionally high number of subcategories statistically significant at 1%. While the countries are on the opposite ends of the political spectrum, it does make sense that they would share commonalities as they are predicted by Jardine’s model to have the highest number of overall Tor users.

Also notable for Authoritarian Regimes are the two categories significant at 1% with positive coefficients and high r-squared values: “Reject economic cooperation” and “Refuse to ease economic sanctions, boycott, or embargo.” Together these reveal Tor users in authoritarian regimes are likely motivated most by the state of the economy. In context, it can also be assumed that these would be actions taken by the international community rather than the authoritarian government itself. While sanctions and lack of cooperation are triggered most often by authoritarian governments’ actions and their refusal to change, it is notable that a declaration from another country likely affects Tor’s use most in authoritarian countries. Additionally, a bad economy might indicate a lack of technological infrastructure; however, the coefficients are positive.[108] This may provide evidence for the success of internet technology nonprofits or reveal the priorities of the authoritarian regimes. As they need the internet too – internet blackouts are indeed net harm to those in power[109] – it may make sense for them to invest in such technology even if they allowed other aspects of the economy to fail. It may also be that the failing economy causes unrest within the country, and governments increasingly block apps citizens use to circumvent censorship. One such instance was when Iran blocked Telegram and other social media platforms after citizens began to protest ‘economic hardships and political repression’ in December 2017.[110]

Following the trends of the Democracy Index Report tests described above, both event categories with significant, high values in Flawed Democracies indicate a potential change of the regime type. One category with a positive coefficient is explicitly titled, “Appeal for change in institutions, regime.” The other is “Ease state of emergency or martial law.” Both describe periods of political transition, the latter primarily pointing towards an increase in democracy. While citizens may have a motivation to use Tor to organize in the former instance, they may turn towards Tor in the latter as consequences for using the software may decrease along with emergency or martial laws. Tor use appears to decrease in Flawed Democracies when there is an “Accede to demands for change in institutions, regime.” If citizens were using Tor to organize, they would likely ease use once their demands were met, and this category certainly aligns with that idea.[111]

Trends revealed by Hybrid Regimes are slightly counterintuitive. “Ease political dissent” has a high r-squared value and is significant at 1% with a positive coefficient. This category follows similar reasoning as Flawed Democracies and “Ease state of emergency or martial law.” However, the event category with similar statistics and a negative coefficient is “Demand policy change.” As many Hybrid Regimes do not score very high in EIU’s measure of Civil Liberties, it would be expected that citizens would turn to a program that provides them with anonymity to organize and protest. However, perhaps this reveals a broader trend of internet blackouts imposed by Hybrid Regimes during periods of unrest, such as the case in Uganda where the internet was shut down for over 100 hours for the election. Even after citizens regained access, they found that most social media websites were blocked.[112]

6.3 Transparency Reports

A high p-value, indicating insignificance, was surprising concerning Apple’s compliance with government requests to remove apps. Primarily, the surprise came from the attention Apple has received in recent years for such actions. At the 2020 State of the Onion conference, Nathan Freitas discussed the Worldwide Developers Against Apple Censorship Conference. It was scheduled simultaneously as the Apple Worldwide Developer Conference to take a stand against Apple’s removal of VPNs and other apps from both the iPhone and Mac app stores.[113] However, it must be noted that with 30 observations, Apple’s category of App Removals did have the lowest number of observations out of any other category tested, and thus, the low sample size may have affected the accuracy of the results.

Notably, Facebook’s highest r-squared value came to be Legal Process Requests, while the lowest was Content Restricted. While one might expect Content Restricted to be higher, as it is an immediately noticeable government action, it may be that users are unaware the government is behind it. If they believe the post was taken down for a violation of Facebook guidelines, moving to Tor would not necessarily help them, as they would still be subject to the same platform rules. Further, as a Legal Process Request means Facebook had to receive a subpoena or some other court order for the information, such a request is likely much more impactful on a user’s life than getting a post taken down. Receiving tangible, legal consequences is sure to induce more fear than content restriction, especially as it comes from the government, whereas users’ knowledge around restrictions is indeterminate.[114]

The significance of Total Accounts Requested with Twitter may be able to be attributed to the large “sweeps” that Twitter conducts, banning numerous accounts allegedly in violation of a certain policy all at once. When the violation seems to be of membership in a minority group rather than an actual policy mistake, people notice. A prominent example of this was the ban of numerous Chinese dissidents before the 30th anniversary of Tiananmen Square in June 2019.[115] It is possible that these large sweeps not only incentivize those kicked off of the platform to move to Tor but also anyone part of the same group whose account happened to “survive.” As this is likely a trend across most Twitter categories, it is understandable why the ANOVA tests performed with the platform’s variables returned the highest r-squared values of the three social media websites.[116]

6.4 Internet Technology

Overall, it does not appear that there is any significant correlation between a country’s Tor Metrics and their Global Connectivity Index score. However, the higher r-squared values do reveal a connection between the use of Tor and the number of Secure Internet Servers a country has, as expected. While this correlation is relatively self-explanatory – Tor requires internet – it is crucial to keep in mind the rising number of government-imposed Internet blackouts. It is also interesting to note that while the r-squared values of 0.6739 and 0.7950 are relatively higher, they are certainly not the highest presented when looking at the test results across all datasets.[117]

7. Limitations

The primary limitation while conducting this research was the size of the dataset. Many programs were unable to process the approximately 1.4 million observations included. It was important that the parameters for querying GDELT were carefully set to ensure as little cleaning as possible was needed after download. However, the size was a net benefit as it allowed for multiple points of analysis and more confident conclusions. Furthermore, as human behavior is naturally more variable, r-squared values were anticipated to be lower. Having a larger sample size counteracted this in many ways. Lastly, it is relevant to note that GDELT is not able to detect actor and country codes for every news story it processes, so there were likely events whose “type” or “location” codes were not picked up and thus were not included in the set. Ideally, many internet users per country would have also been included alongside the Global Connectivity Index and several secure internet servers per country; however, much data is missing, especially from the smaller, often more authoritarian countries. While World Bank conducted a complete survey in 2017 and 2019, that would have left 2016, 2018, and 2020 null and unaccounted for.

8. Conclusion

GDELT revealed many exciting patterns and points when analyzed alongside the Tor Metrics, mainly when such data was divided by government type. In the future, it would be helpful to analyze such data points further to understand better which country is the one acting which way—particularly looking at the variable “Fight” shared between Full Democracies and Authoritarian Regimes. It might be that users in Full Democracies are more likely to use Tor when their country is threatening to fight another country. In contrast, users in Authoritarian regimes might be more likely to use Tor when their country is being fought. It would also be beneficial to construct a database of annual internet user information per country to use as a control variable.

In 2018, Freedom House said, “Global internet freedom can and should be the antidote to digital authoritarianism” and their statement remains just as relevant in 2021.[118] As regimes continue to pass internet surveillance and control laws, censorship circumvention tools like Tor become all the more important, as does our understanding of the software and when and how citizens are currently using it. In gaining knowledge of this, supplementing additional needs and targeting specific points of inaccessibility become easier. By assessing these different datasets, it becomes evident that the use of Tor is highly individual and personal, yet some trends can be drawn between event and government types that may allow for increased support when needed.

Endnotes

[1] Edward Snowden, 2019, Permanent Record, New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 329.

[2] Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health? 2021, London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit, Periodic, 4.

[3] Democracy Index 2020, Economist Intelligence Unit, 6.

[4] Billy Perrigo, 2021, “India’s New Internet Rules Are a Step Toward ‘Digital Authoritarianism,’ Activists Say. Here’s What They Will Mean,” TIME.

[5] Perrigo, “India’s New Internet Rules Are a Step Toward ‘Digital Authoritarianism.’”

[6] Newman, Lily Hay, 2021, “Myanmar’s Internet Shutdown Is an Act of ‘Vast Self-Harm,’” Wired.

[7] Newman, “Myanmar’s Internet Shutdown Is an Act of ‘Vast Self-Harm.’”

[8] Newman, “Myanmar’s Internet Shutdown Is an Act of ‘Vast Self-Harm.’”

[9] “History,” 2011, The Tor Project.

[10] “History,” The Tor Project.

[11] “History,” The Tor Project.

[12] “User Research: Tor Personas,” The Tor Project.

[13] “User Research: Tor Personas,” The Tor Project.

[14] “User Research: Tor Personas,” The Tor Project.

[15] Isabela Bagueros et al. 2020, State Of The Onion 2020, YouTube: The Tor Project.

[16] Isabela Bagueros et al. 2020, State Of The Onion 2020.

[17] Wright, Joss, Alexander Darer, and Oliver Farnan, 2018, “On Identifying Anomalies in Tor Usage with Applications in Detecting Internet Censorship,” In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science, WebSci ’18, New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 96.

[18] Ramesh, Reethika et al. 2020, “Decentralized Control: A Case Study of Russia,” In Proceedings 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA: Internet Society, 2-3.

[19] Ramesh, et al, “Decentralized Control: A Case Study of Russia,” 13.

[20] Weinberg, Zachary, Mahmood Sharif, Janos Szurdi, and Nicolas Christin, 2017, “Topics of Controversy: An Empirical Analysis of Web Censorship Lists,” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies 2017(1): 43.

[21] Weinberg, Sharif, Szurdi, and Christin, “Topics of Controversy,” 56.

[22] Hobbs, William R., and Margaret E. Roberts, 2018, “How Sudden Censorship Can Increase Access to Information,” American Political Science Review 112(3): 621.

[23] Hobbs and Roberts, “How Sudden Censorship Can Increase Access to Information,” 621, 623.

[24] Hobbs and Roberts, “How Sudden Censorship Can Increase Access to Information,” 629.

[25] Raje, Anand, and Sushanta Sinha, 2020, “Anonymous Traffic Networks,” In The “Essence” of Network Security: An End-to-End Panorama, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, eds. Mohuya Chakraborty, Moutushi Singh, Valentina E. Balas, and Indraneel Mukhopadhyay, Singapore: Springer, 282.

[26] Thorsten Thiel, 2021, “Anonymity: The Politicisation of a Concept,” In Book of Anonymity, ed. Anon Collective, Brooklyn, NY: punctum books, 105.

[27] Randall Amster, 2021, “Mapping Digital Justice: Across the Great Divide, Towards a Sanctuary for All,” Journal of Transdisciplinary Peace Praxis 3(1): 154.

[28] Amster, “Mapping Digital Justice: Across the Great Divide, Towards a Sanctuary for All,” 158.

[29] Alex Linton et al, 2021, Ground Safe: Assessing the Digital Security Needs and Practices of Human Rights Defenders in Africa, MENA, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, Melbourne: Oxen Privacy Tech Foundation, 10.

[30] Linton et al, Ground Safe, 10.

[31] Linton et al, Ground Safe, 10.

[32] Collier, Ben, 2020, “The Power to Structure: Exploring Social Worlds of Privacy, Technology and Power in the Tor Project,” Information, Communication & Society: 2.

[33] Lindner, Andrew M., and Tongtian Xiao. 2020, “Subverting Surveillance or Accessing the Dark Web? Interest in the Tor Anonymity Network in U.S. States, 2006–2015,” Social Currents 7(4): 355.

[34] Collier, “The Power to Structure,” 12.

[35] Lund, Brady, and Matt Beckstrom, 2019, “The Integration of Tor into Library Services: An Appeal to the Core Mission and Values of Libraries,” Public Library Quarterly 40(1): 62.

[36] Lund and Beckstrom, “The Integration of Tor into Library Services,” 62.

[37] Lindner and Xiao, “Subverting Surveillance or Accessing the Dark Web?” 365.

[38] Alex Marthews and Catherine Tucker, 2017, “Government Surveillance and Internet Search Behavior,” Social Science Research Network, 1.

[39] Lindner and Xiao, “Subverting Surveillance or Accessing the Dark Web?” 362.

[40] Gehl, Robert W, 2018b, Weaving the Dark Web: Legitimacy on Freenet, Tor, and I2P, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 121.

[41] Jansen, Rob, Justin Tracey, and Ian Goldberg, 2021, “Once Is Never Enough: Foundations for Sound Statistical Inference in Tor Network Experimentation,” 1.

[42] “Uniform Country Names – R” (see Appendix B).

[43] Doze, Mohammed Le, 2020, Countries, JSON, CSV, XML.

[44] “Cleaning CSVs – R” (see Appendix B).

[45] “Merging Tor CSVs – R” (see Appendix B).

[46] “Users – Tor Metrics,” 2014, The Tor Project.

[47] “Relay Scrape – Python” (see Appendix B).

[48] “Bridge Scrape – Python” (see Appendix B).

[49] Democracy Index 2016: Revenge of the “Deplorables.” 2017, London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit, Periodic.

[50] Democracy Index 2020, Economist Intelligence Unit.

[51] “GD003,” 2018.

[52] Privacy, 2018, Apple, Transparency.

[53] Removal Requests, 2021, Twitter, Transparency.

[54] Case Studies: Content Restrictions Based on Local Law, 2020, Menlo Park, CA: Facebook, Transparency.

[55] Government Requests for User Data, 2020, Menlo Park, CA: Facebook, Transparency.

[56] GCI 2020: Shaping the New Normal with Intelligent Connectivity, 2021, Shenzhen, China: Huawei, Periodic.

[57] NetCraft, 2016, “Secure Internet Servers (per 1 Million People).”

[58] “Data: Querying, Analyzing and Downloading,” 2013, The GDELT Project.

[59] Schrodt, Philip A, 2012, CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, Codebook.

[60] Figure 1, Average Tor Users, GCI Scores, and Secure Internet Servers per 1 million people (see Appendix A).

[61] GCI 2020, Huawei.

[62] Figure 2, Average Tor Users and Economic Intelligence Unit Democracy Index scores (see Appendix A).

[63] Figure 6, Average Tor Users and EIU Democracy Index scores in Authoritarian Regimes (see Appendix A).

[64] Figure 5, Average Tor Users and EIU Democracy Index scores in Hybrid Regimes (see Appendix A).

[65] Figure 4, Average Tor Users and EIU Democracy Index scores in Flawed Democracies (see Appendix A).

[66] Figure 3, Average Tor Users and EIU Democracy Index scores in Full Democracies (see Appendix A).

[67] Democracy Index 2016, Economist Intelligence Unit.

[68] Democracy Index 2015: Democracy in an Age of Anxiety, 2016, London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit, Periodic.

[69] Democracy Index 2017: Free Speech under Attack. 2018. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic.

[70] Democracy Index 2018: Me Too? Political Participation, Protest and Democracy. 2019. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic.

[71] Democracy Index 2019: A Year of Democratic Setbacks and Popular Protest, 2020, London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit, Periodic.

[72] Democracy Index 2020, Economist Intelligence Unit, 7.

[73] Democracy Index 2020, Economist Intelligence Unit, 3.

[74] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_Events” (see Appendix B).

[75] “GDELT Codes – A Compilation of CAMEO and Other GDELT Codebooks” (See Appendix B).

[76] Figure 10, Tor and GDELT in Full Democracies (see Appendix B).

[77] Figure 11, Tor and GDELT in Flawed Democracies (see Appendix B).

[78] Figure 12, Tor and GDELT in Hybrid Regimes (see Appendix B).

[79] Figure 13, Tor and GDELT in Authoritarian Regimes (see Appendix B).

[80] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_Events_Breakdown” (see Appendix B).

[81] Figure 7, Average Tor Users and Government Interactions with Apple (see Appendix A).

[82] Figure 8, Average Tor Users and Government Interactions with Facebook (see Appendix A).

[83] Figure 9, Average Tor Users and Government Interactions with Twitter (see Appendix A).

[84] “Compiled Tables: GCI_Secure_Internet_Servers” (see Appendix B).

[85] “Compiled Tables: EIU_Aggregated” (see Appendix B).

[86] “Compiled Tables: EIU_Full_Democracies” (see Appendix B).

[87] “Compiled Tables: EIU_Flawed_Democracies” (see Appendix B).

[88] “Compiled Tables: EIU_Hybrid_Regimes” (see Appendix B).

[89] “Compiled Tables: EIU_Authoritarian Regimes” (see Appendix B).

[90] “Compiled Tables: EIU_One_Sheet” (see Appendix B).

[91] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_Events” (see Appendix B).

[92] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_Events_Breakdown” (see Appendix B).

[93] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Full” (see Appendix B).

[94] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Flawed” (see Appendix B).

[95] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Hybrid” (see Appendix B).

[96] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Authoritarian” (see Appendix B).

[97] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Full” (see Appendix B).

[98] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Full” (see Appendix B).

[99] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Flawed” (see Appendix B).

[100] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Hybrid” (see Appendix B).

[101] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Authoritarian” (see Appendix B).

[102] “Compiled Tables: Apple” (see Appendix B).

[103] “Compiled Tables: Facebook” (see Appendix B).

[104] “Compiled Tables: Twitter” (see Appendix B).

[105] Jardine, Eric. 2016. “Tor, What Is It Good for? Political Repression and the Use of Online Anonymity-Granting Technologies.” New Media & Society 20(2): 435.

[106] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Authoritarian” (see Appendix B).

[107] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Full” (see Appendix B).

[108] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Authoritarian” (see Appendix B).

[109] Newman, “Myanmar’s Internet Shutdown Is an Act of ‘Vast Self-Harm.’”

[110] Linton et al, Ground Safe, 30.

[111] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Flawed” (see Appendix B).

[112] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Hybrid” (see Appendix B).

[113] Isabela Bagueros et al, State Of The Onion 2020.

[114] “Compiled Tables: GDELT_EIU_Facebook” (see Appendix B).

[115] Mozur, Paul. 2019. “Twitter Takes Down Accounts of China Dissidents Ahead of Tiananmen Anniversary.” The New York Times.

[116] “Compiled Tables: Summary” (see Appendix B).

[117] “Compiled Tables: Summary” (see Appendix B).

[118] Mai Truong, Jessica White, Allie Funk, and Adrian Shahbaz. 2018. Freedom on the Net 2018: The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic.

Bibliography

Alex Marthews and Catherine Tucker. 2017. “Government Surveillance and Internet Search Behavior.” Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2412564.

Alex Linton et al. 2021. Ground Safe: Assessing the Digital Security Needs and Practices of Human Rights Defenders in Africa, MENA, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Melbourne, Aus: Oxen Privacy Tech Foundation. https://www.blueprintforfreespeech.net/s/Ground-Safe-Report.pdf.

Al-Saqaf, Walid. 2016. “Internet Censorship Circumvention Tools: Escaping the Control of the Syrian Regime.” Media and Communication 4(1): 39–50. https://www.cogitatiopress.com/mediaandcommunication/article/view/357/357.

Berhan Taye. 2021. Shattered Dreams and Lost Opportunities: A Year in the Fight to #KeepItOn. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/cms/assets/uploads/2021/03/KeepItOn-report-on-the-2020-data_Mar-2021_3.pdf.

Billy Perrigo. 2021. “India’s New Internet Rules Are a Step Toward ‘Digital Authoritarianism,’ Activists Say. Here’s What They Will Mean.” TIME. https://time.com/5946092/india-internet-rules-impact/.

Boyd, Maia J., Jamar L. Sullivan Jr., Marshini Chetty, and Blase Ur. 2021. “Understanding the Security and Privacy Advice Given to Black Lives Matter Protesters.” In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’21, New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 1–18. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3411764.3445061.

Brendan Knapp. 2017. Evaluating GDELT: Syrian Conflict. R. https://rpubs.com/BrendanKnapp/GDELT_Syrian_Conflict.

Brian Sandberg. 2017. “The Geography of Anonymous Communications: Detecting Online Censorship Events.” Journal of Mason Graduate Research 5(1): 17–36. https://journals.gmu.edu/index.php/jmgr/article/view/1782/1375 (June 1, 2021).

Carmela Troncoso, Daniel Kahn Gillmor, Matt Mitchell, and Roger Dingledine. 2020. PrivChat with Tor | Online Privacy in 2020: Activism & COVID-19. YouTube: The Tor Project. https://youtu.be/gSyDvG4Z30.

Case Studies: Content Restrictions Based on Local Law. 2020. Menlo Park, CA: Facebook. Transparency. https://transparency.fb.com/data/content-restrictions/case-studies.

Coffey, Mollie L. 2020. “Library Application of Deep Web and Dark Web Technologies.” SRJ 10(1). https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1335&context=ischoolsrj.

Collier, Ben. 2020. “The Power to Structure: Exploring Social Worlds of Privacy, Technology and Power in the Tor Project.” Information, Communication & Society: 1–17. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1732440.

“Data: Querying, Analyzing and Downloading.” 2013. The GDELT Project. https://www.gdeltproject.org/data.html.

Democracy Index 2015: Democracy in an Age of Anxiety. 2016. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.yabiladi.com/img/content/EIU-Democracy-Index-2015.pdf.

Democracy Index 2016: Revenge of the “Deplorables.” 2017. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=DemocracyIndex2016.

Democracy Index 2017: Free Speech under Attack. 2018. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=DemocracyIndex2017.

Democracy Index 2018: Me Too? Political Participation, Protest and Democracy. 2019. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=Democracy2018.

Democracy Index 2019: A Year of Democratic Setbacks and Popular Protest. 2020. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.eiu.com/public/topical_report.aspx?campaignid=democracyindex2019.

Democracy Index 2020: In Sickness and in Health? 2021. London, UK: Economist Intelligence Unit. Periodic. https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2020/.

Deniz D. Aydin, Mike Posner, and Dragana Kaurin. 2016. Migrants, Surveillance & Human Rights: How to Escape the Security Paradigm – The Hub. YouTube: Access Now. https://youtu.be/GzrMJWQ8EZ0.

Doze, Mohammed Le. 2020. Countries. . JSON, CSV, XML. https://github.com/mledoze/countries.

Dunna, Arun, Ciarán O’Brien, and Phillipa Gill. 2018. “Analyzing China’s Blocking of Unpublished Tor Bridges.” In Baltimore, MD, 1–7. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/foci18/foci18-paper-dunna.pdf.

Edward Snowden. 2019. Permanent Record. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books. https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/permanent-record-edward-snowden/1132756213.

Ensafi, Roya, Alex Halderman, and Stephen Schultze. 2015. CITP Panel 2: Assessing the State of Internet Accessibility. YouTube: CITP Princeton. https://youtu.be/Zc88ibkJgAo.

Freyburg, Tina, and Lisa Garbe. 2017. “Authoritarian Practices in the Digital Age | Blocking the Bottleneck: Internet Shutdowns and Ownership at Election Times in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Journal of Communication 12(0): 3896–3916. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8546/2464.

GCI 2020: Shaping the New Normal with Intelligent Connectivity. 2021. Shenzhen, China: Huawei. Periodic. https://www.huawei.com/minisite/gci/en/.

“GD003.” 2018. https://www.gapminder.org/data/documentation/democracy-index/.

Gehl, Robert W. 2018a. “Archives for the Dark Web: A Field Guide for Study.” In Research Methods for the Digital Humanities, eds. Lewis Levenberg, Tai Neilson, and David Rheams. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96713-4_3 (June 1, 2021).

———. 2018b. Weaving the Dark Web: Legitimacy on Freenet, Tor, and I2P. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/weaving-dark-web.

Government Requests for User Data. 2020. Menlo Park, CA: Facebook. Transparency. https://transparency.fb.com/data/government-data-requests/.

Hadley Wickham. Bigrquery. . R. https://github.com/r-dbi/bigrquery (May 26, 2021).

“History.” 2011. The Tor Project. https://www.torproject.org/about/history/.

Hobbs, William R., and Margaret E. Roberts. 2018. “How Sudden Censorship Can Increase Access to Information.” American Political Science Review 112(3): 621–36. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/A913C96E2058A602F611DFEAC43506DB/S0003055418000084a.pdf/how-sudden-censorship-can-increase-access-to-information.pdf.

Information Requests. 2020. Twitter. Transparency. https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/information-requests.html.

Internet Shutdown Tracker. 2021. New Delhi, India: Software Freedom Law Centre. https://internetshutdowns.in.

Isabela Bagueros et al. 2020. State Of The Onion 2020. Youtube: The Tor Project. https://youtu.be/IyWyTypRGWQ.

Iszaevich, Gunnar Eyal Wolf. 2019. “Distributed Detection of Tor Directory Authorities Censorship in Mexico.” In Valencia, Spain: International Academy, Research, and Industry Association, 82–86. https://censorbib.nymity.ch/pdf/Iszaevich2019a.pdf.

Jansen, Rob, Justin Tracey, and Ian Goldberg. 2021. “Once Is Never Enough: Foundations for Sound Statistical Inference in Tor Network Experimentation.” http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.05196.

Jardine, Eric. 2016. “Tor, What Is It Good for? Political Repression and the Use of Online Anonymity-Granting Technologies.” New Media & Society 20(2): 435–52. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1461444816639976.

Kelly, Sanja et al. 2017. Freedom on the Net 2017: Manipulating Social Media to Undermine Democracy. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/Freedom_on_the_Net_2017_complete_book.pdf.

Kelly, Sanja, Mai Truong, Adrian Shahbaz, and Madeline Earp. 2016. Freedom on the Net 2016: Silencing the Messenger – Communication Apps under Pressure. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FOTN_2016_BOOKLET_FINAL.pdf.

Lee, Linda et al. 2017. “A Usability Evaluation of Tor Launcher.” Proceedings on Privacy Enhancing Technologies 2017(3): 90–109. https://www.sciendo.com/article/10.1515/popets-2017-0030.

Li, Zhihao, Stephen Herwig, and Dave Levin. 2017. “DeTor: Provably Avoiding Geographic Regions in Tor.” In Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium, Vancouver, BC: USENIX Association, 343–59. https://www.usenix.org/system/files/conference/usenixsecurity17/sec17-li.pdf.

Libya Idres et al. 2021. Arab Spring: Ten Years in, How Can We Reclaim the Internet as an Open Space? YouTube: Access Now. https://youtu.be/cVu4qnQ-yP4.

Lindner, Andrew M., and Tongtian Xiao. 2020. “Subverting Surveillance or Accessing the Dark Web? Interest in the Tor Anonymity Network in U.S. States, 2006–2015.” Social Currents 7(4): 352–70. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2329496520919165.

Loesing, Karsten, Steven J. Murdoch, and Roger Dingledine. 2010. “A Case Study on Measuring Statistical Data in the Tor Anonymity Network.” In Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, eds. Radu Sion et al. Heidelberg: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 203–15. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-642-14992-4_19.

Lund, Brady. 2019. “The Dark Web for All! Why This Polarizing ‘Crime Haven’ Might Just Be Our Best Chance to Preserve Our Right to Privacy and Intellectual Freedom.” Journal of Information Ethics 28(2): 109–16. http://www.proquest.com/docview/2317012446/abstract/4FCB003EF52248B1PQ/1.

Lund, Brady, and Matt Beckstrom. 2019. “The Integration of Tor into Library Services: An Appeal to the Core Mission and Values of Libraries.” Public Library Quarterly 40(1): 60–76. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01616846.2019.1696078.

Mai Truong, Jessica White, Allie Funk, and Adrian Shahbaz. 2018. Freedom on the Net 2018: The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/10192018_FOTN_2018_Final_Booklet.pdf.

Mirea, Mihnea, Victoria Wang, and Jeyong Jung. 2018. “The Not so Dark Side of the Darknet: A Qualitative Study.” Secur. J. 32(2): 102–18. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057%2Fs41284-018-0150-5#citeas.

Moises Rendon and Arianna Kohan. 2019. “The Internet: Venezuela’s Lifeline.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/internet-venezuelas-lifeline.

Mozur, Paul. 2019. “Twitter Takes Down Accounts of China Dissidents Ahead of Tiananmen Anniversary.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/01/business/twitter-china-tiananmen.html.

NetCraft. 2016. “Secure Internet Servers (per 1 Million People).” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.SECR.P6.

Newman, Lily Hay. 2021. “Myanmar’s Internet Shutdown Is an Act of ‘Vast Self-Harm.’” Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/myanmar-internet-shutdown.

“Nicaragua: Ortega Government Appears to Be Preparing for a New Phase of Repression.” 2020. Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/09/nicaragua-gobierno-pareciera-preparar-nueva-fase-represion/.

Okunoye, Babatunde. 2020. Censored Continent: Understanding the Use of Tools during Internet Censorship in Africa. Nigeria: Open Technology Fund. Information Controls Fellowship Research Report. https://research.torproject.org/techreports/icfp-censored-continent-2020-07-31.pdf.

Patrick Howell O’Neill. 2020. “A Dark Web Tycoon Pleads Guilty. But How Was He Caught?” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/02/08/349016/a-dark-web-tycoon-pleads-guilty-but-how-was-he-caught/.

Philipp Winter. 2020. “Circumventing Internet Censorship with Tor.” Presented at the OONI Internet Measurement Village 2020, YouTube. https://youtu.be/g6xEfNHkFKY.

Privacy. 2018. Apple. Transparency. https://www.apple.com/legal/transparency/.

Raje, Anand, and Sushanta Sinha. 2020. “Anonymous Traffic Networks.” In The “Essence” of Network Security: An End-to-End Panorama, Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, eds. Mohuya Chakraborty, Moutushi Singh, Valentina E. Balas, and Indraneel Mukhopadhyay. Singapore: Springer, 263–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9317-8_11.

Ramesh, Reethika et al. 2020. “Decentralized Control: A Case Study of Russia.” In Proceedings 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium, San Diego, CA: Internet Society, 1–18. https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/23098.pdf.

Randall Amster. 2021. “Mapping Digital Justice: Across the Great Divide, Towards a Sanctuary for All.” Journal of Transdisciplinary Peace Praxis 3(1): 145–166. http://bit.ly/mappingdigitaljustice.

Removal Requests. 2021. Twitter. Transparency. https://transparency.twitter.com/en/reports/removal-requests.html#2020-jan-jun.

“Reporters Without Borders Launches Digital Help Desk.” 2019. Reporters Without Borders. https://rsf.org/en/news/reporters-without-borders-launches-digital-help-desk.

Roger Dingledine. 2019. Roger Dingledine – The Tor Censorship Arms Race The Next Chapter – DEF CON 27 Conference. YouTube: DEFCONConference. https://youtu.be/ZB8ODpw_om8 (June 1, 2021).

Ron Deibert, Edward Snowden, and Amie Stepanovich. 2016. Fireside Chat: Ron Deibert, Edward Snowden & Amie Stepanovich – The Hub. YouTube: Access Now. https://youtu.be/yGDqXokPGiE.

Russell, Nathan. 2017. Hashmap. . R. https://github.com/nathan-russell/hashmap.

“Russia: Growing Internet Isolation, Control, Censorship.” 2020. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/06/18/russia-growing-internet-isolation-control-censorship.

Sanchez-Rola, Iskander, Davide Balzarotti, and Igor Santos. 2017. “The Onions Have Eyes: A Comprehensive Structure and Privacy Analysis of Tor Hidden Services.” In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Republic and Canton of Geneva, CHE: International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, 1251–60. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3038912.3052657.

Schrodt, Philip A. 2012. CAMEO Conflict and Mediation Event Observations Event and Actor Codebook. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University. Codebook. http://data.gdeltproject.org/documentation/CAMEO.Manual.1.1b3.pdf.

Senker, Cath. 2019. Cybercrime & the Dark Net: Revealing the Hidden Underworld of the Internet. London, UK: Arcturus. https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/cybercrime-and-the-dark-net-cath-senker/1132648567.

Seo, Hyunjin et al. 2021. “Country Characteristics, Internet Connectivity and Combating Misinformation: A Network Analysis of Global North-South.” In University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2966–75. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/70975/0290.pdf.

Shahbaz, Adrian et al. 2020. Freedom on the Net 2020: The Pandemic’s Digital Shadow. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/10122020_FOTN2020_Complete_Report_FINAL.pdf.

Singh, Kushagra, Gurshabad Grover, and Varun Bansal. 2020. “How India Censors the Web.” In WebSci ’20, New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 21–28. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3394231.3397891.

“Special Cybercrime Bill in Nicaragua Promotes Censorship and Criminalizes the Everyday Use of Technologies.” 2020. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/nicaragua-cybercrime-bill-promotes-censorship/.

Sundara Raman, Prerana Shenoy, Katharina Kohls, and Roya Ensafi. 2020. “Censored Planet: An Internet-Wide, Longitudinal Censorship Observatory.” In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS ’20, New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, 49–66. https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3372297.3417883.

Thorsten Thiel. 2021. “Anonymity: The Politicisation of a Concept.” In Book of Anonymity, ed. Anon Collective. Brooklyn, NY: punctum books, 88–109. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/231508.

Truong, Mai, Amy Slipowitz, Isabel Linzer, and Noah Buyon. 2019. Freedom on the Net 2019: The Crisis of Social Media. Washington, D.C.: Freedom House. Periodic. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/11042019_Report_FH_FOTN_2019_final_Public_Download.pdf.

“Uganda Election: Internet Restored but Social Media Blocked.” 2021. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-55705404.

UNESCO Observatory of Killed Journalists. 2017. Paris, France: UNESCO. United Nations. https://en.unesco.org/themes/safety-journalists/observatory.

“User Research: Tor Personas.” 2021. The Tor Project. https://community.torproject.org/user-research/persona/.

“Users – Tor Metrics.” 2014. The Tor Project. https://metrics.torproject.org/userstats-relay-country.html.