A love letter to mine, the new lost generation

We’re in the home stretch. I keep hearing people say this. Cases are falling, vaccine supply is up, the CDC says immunized people can gather indoors, maskless! President Biden practically invited us to his fourth of July Barbecue. There are still worries of a final wave, so hold tight, we’re not there yet. Double mask. Get tested. Keep your six feet. Just until everyone can get a shot. Then we’ll be good.

I don’t buy it. We’ll stop losing so many lives, yes, and the impossibly heavy weight of the daily death toll will lift. But there’s another catastrophe looming, one having more to do with our hearts than our lungs. And I’m worried my peers and I aren’t ready for it.

I’m not a doctor or a statistician. All I can say is what I feel. And what I feel is that today’s teens and twenty-somethings, who have ridden out this pandemic year separated from their peers, missing birthdays, first dates, proms and graduations — they’re about to get hit. When lockdown lifts, the euphoria will be a fast and cheap high; and young people are going to crash hard, buried by a mental health crisis and left to reckon with the trauma.

Varun Soni, the dean of spiritual life at USC, and the university’s chaplain, is also worried. Soni says the problems didn’t start with the pandemic. He has seen a steady increase in anxiety and depression among students over the last six years. It wasn’t until he started hearing about the same phenomenon from colleagues at different universities across the country though, that he realized there was a larger trend. Research shows that 65% of college students say they’re overwhelmed by anxiety, he tells me, and 10% have had thoughts of suicide over the past year.

“What I began to see is an underlying, I would say, spiritual crisis” Soni says. “A deep and abiding sense of loneliness and disconnection.” The data suggest these aren’t just growing pains. In 2018, a study by Cigna health insurance found that nearly 50% of Americans were suffering from loneliness. In the subsequent two years, those numbers rose to 61%. That means 3 in 5 Americans were regularly experiencing feelings of loneliness. And those suffering the most? Not retirees, or the unmarried, or the childless. It was young people. “The loneliest people in the country are post-millennials, and specifically 18 to 22 year olds,” he says. “The loneliest people in the country are college aged students.”

What does it mean to be lonely? Since the symptoms vary by individual it remains a generally amorphous concept and its danger is often overlooked. But the truth is that loneliness can be just as threatening as any other diagnosable condition.

Surgeon General Vivek Murthy called attention to the “loneliness epidemic”when he served in the Obama administration. During his time treating patients, Murthy said that the pathology he saw the most was not heart disease or diabetes, but loneliness. In 2020 he published a book entitled “Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World,” arguing that fostering human connection is about more than just a meaningful life, it’s about safeguarding public health.

The statistics he cites will make you want to pick up the phone and call someone. In 2010 a study published in the Public Library of Science (PLOS) journal found that those with strong social relationships had a 50% higher likelihood of survival. That statistic was constant across all variables — age, sex, health status, even principal cause of death.The study concluded that an individual’s lack of connection to other human beings is on par with other well-established risk factors for mortality. It turns out you may need a friend more than you need that green smoothie or nicotine patch.

Tim Smith, one of the authors of the study and a fellow of the American Psychology Association, says that sometimes people don’t know how to ward off loneliness. “What our system thrives on is intimacy, genuine connection” he explains, “And by intimate I don’t mean sexual. I mean emotionally safe, very free, relationships.” In the digital age, we fool ourselves into thinking that we’re connected because we have so many Facebook Friends.’ Smith argues that while platforms like Facebook and Instagram may seem “social” they don’t foster the kinds of dependable and emotionally raw relationships that curb loneliness and social isolation.

While some scientists are reluctant to tie the loneliness spike in younger populations to the rise of social media, Dr. Soni is not so shy. “It’s technology” he says bluntly. “It’s the difference between this generation and every previous generation. For a hundred thousand years, we’ve communicated with our tongues; for your generation, you’re communicating with your thumbs.”

Vapid relationships predate the invention of the iPhone, but Soni’s point is that this cohort, my cohort actually, has been the guinea pigs for an experiment with a new form of community that doesn’t demand authentic engagement. If surviving requires two or three soul-mates, big tech isn’t going to be your matchmaker. That’s because it wasn’t designed to be. Soni points to the fact that a number of silicon valley CEOs send their kids to Waldorf Schools — known for their holistic approach to education and their strict limits on technology. “It’s a drug” he says, “they know what they’re making. They don’t get high on their own supply.”

“Why is it the young people today are more anxious than they were during World War II, and more depressed than they were during the great depression? ” Soni asks. My best guess is it has something to do with the 24-hour broadcast of societal decay. Soni agrees. “People weren’t constantly being inundated by an incredible amount of data that highlights how bad the world is, how difficult everything is,” he says of previous generations.

It isn’t that the world has been suddenly poisoned, to some extent it has always been this way, it’s just now we know everything about it. The digital boom has hacked our artificial boundaries and all the misery and tragedy of human existence is up for consumption. This makes the loneliness remedy — human connection — all the more important. If the world is so terribly broken the very least we’ll need is someone to share in that brokenness with, or better yet, to teach that the brokenness isn’t new, and that when acknowledged it can help. “We actually exist on this planet for each other,” Smith explains. “If we face it just one generation slice alone, then we’re kind of missing the boat that we’re all interconnected.”

It’s lonesome to be young, particularly now, and the data backs that up. We are set to become the next lost generation — straining on our tip-toes to reach the threshold of resilience, and doing our best to shout down the demons of false connection and tragedy overload. But maybe we can keep our next Hemingway at bay by learning from those who came before us. Smith puts it more elegantly. “Every generation needs one another right now” he tells me, “human resilience is the lesson of history — we made it, our ancestors made it, this is not the bubonic plague. It was horrific, but by golly we are connected by bonds that are extremely powerful.”

* * *

Early in 2020, when the world shut down, I found myself missing my grandparents. All four of them passed before I graduated high school, but suddenly I started to feel their loss in a different way. It was less abstract — I wanted to ask how they had held steady when their world trembled. They were my age during the Great Depression and World War II.

On my mothers side, my grandmother used to tell this story about how she married my grandfather in a hastily planned ceremony before he shipped off to war. They cancelled the wedding they had planned, and she packed her wedding dress in a suitcase and took the train from Sacramento to Lake City, Florida by herself (quite the scandal in 1945). She got married in cardboard hotel slippers, walked herself down the aisle, and the best man dropped the wedding cake, so it listed a little to the side. They were married for 68 years. The password to every computer in their house was LakeCity1.

I think about that story once a week, especially when my roommates and I are sitting around feeling sorry for ourselves. When I learned that graduation had been cancelled, I closed my eyes and pictured a plastic bride and groom teetering on the edge of a lopsided cake.

I don’t know how healthy of a coping mechanism it is to use my ancestors’ strife to contextualize my own, but it reminds me of the durability of humankind. Why slice up society into cohorts — Millennials, Gen X, Boomers — if we don’t reach across the divide to learn something from one another.

In 2009, Elly Katz, a former graphic designer, started a program in Los Angeles to combat ageism called Sages and Seekers. Katz’s idea was to match elders, “sages” so to speak, with teens and twenty-somethings. Katz tells me she felt the two “marginalized groups” had something important to offer each other. What’s more, they enjoyed one another.

It’s not a mentorship program, Katz wants me to know. In fact those are the rules: No lecturing, no judging, no unsolicited advice. It’s about shared connection and mutual understanding. The elders get an “emotional paycheck” for the lives they’ve lived and to pass their hard-earned lessons to the next generation. Katz learned about it from the German psychoanalyst Erik Erikson. Erikson argued that middle adulthood brings a need for human beings to leave some tangible impact on the world that created them. His work also advanced the theory that the psychological healing process has a lifespan much longer than just the formative years, and that experiences later on can retroactively ease childhood trauma. So young and older people both benefit.

Katz sees herself as a sort of matchmaker creating a vital nexus between the old and the young. “You can chit-chat all day long,” she says of the need for deep social connection “but if you don’t really feel seen and you don’t feel like you’ve had an authentic exchange, then how can you feel like you belong somewhere?”

She tells me about an eight year old woman who had an epiphany about her father while talking to her younger counterpart. And about a teen mom who felt supported and capable based on the comments of her “sage.” As we talked I felt that same longing. I wanted to talk to my grandparents or, in any case, someone’s grandparents. So I sat with the sages — four of them: Mark Robinson, Chris Hughes, Loni Brown, and Bonnie Armstrong.

Each one seemed to think categorizing themselves as a “sage” was a bit extreme. As we talked though they dropped wisdom like spare change anyway and I tucked it all away. Afterwards, when I got to counting, I feared I had come up short though. I was looking for infinite wisdom, some universal truths about enduring tragedy, but nothing like that emerged.

The four of them — all in their 60s and 70s — had different ideas on what had granted them wisdom over the years and when I posed ‘the big questions’, like how to bounce back from failure, their answers didn’t seem to come from a common set of truths, they came from real life experiences. Armstrong laughed, in fact, when I asked her and just replied, “denial.” Hughes on the other hand said that I had a lot of room to fail given my age. Any mistake you make now can’t be all that enduring, he explained, because you can reinvent yourself at 35 — he did.

I asked whether the pandemic’s arrival had shaken them any less given their age and they said it really wasn’t that simple. Robinson told me that those extra years allowed him to feel a little less like the world was ending, but that the anxiety still comes and goes. Like me, he finds the nights much harder. Armstrong said she struggled not seeing her family and that there were lonely moments, but she knew it would ultimately come to an end. She described to me hiding under her desk during the ‘60s for nuclear bomb drills and explained that after a while, your worldview becomes steeled by experience.

Once the conversation shifted towards the future, I was surprised at how much hope all of them eagerly offered up. Robinson talked to me about the need to understand the vested interest society has in separating us, and how inspired he had been by the wave of anti-racist activism this past summer. Armstrong told me that this wasn’t the world she and her generation had wanted to leave behind. They thought they were going to change it all, she said, but where they fell short she was confident we would finish the job. She asked me to be an agent for change and reminded me that any true “sage” is just a “seeker” in disguise.

So it seems I did not come up short after all. The virtue of those conversations did not lie in some truism I could use to steady my life. It was instead found inadvertently in the way each one felt like a prolonged exhale; like someone whispering from behind as I took my first steps into a dimensionless abyss: “you’ll be just fine, kid.” Of course they can’t possibly know that, but their existence on the other end of the line feels proof that it could be true.

All American Amnesia : The 1918 Flu and a Lost Opportunity to Mourn

In 2007 Annie Laurie Williams of Selma, Alabama sat down for an interview with the state department of public health to talk about the 1918 Influenza pandemic. Williams was three years old when her father became sick with the flu, but says that she can “clearly and readily” remember how ill he was, and how afraid she and her sister were that he would die. Williams, 91 years old at the time of the interview, says after all these years the pandemic still remains “about the most traumatic experience I’ve had in my life”.

Her father worked at a jewelry company and so many people fell ill they had to close. Doctors made house calls but there was no treatment, so the best they could do was to make the ill comfortable. “My mother took care of him,” William recalls, “and kept us away from him as much as she could.” The neighbors would bring food to the door but never dared step inside.

Williams’ story reminded me of the stories of millions of Americans whose lives were upended by the outbreak. “They can’t possibly understand or even visualize the impact it had on the entire society,” Williams says towards the end of the interview. The “they” in question here is ill-defined. It could be us. And, after all, isn’t it us? Prior to this year, how many Americans could describe a disease stricken society the way it was in 1918? In Mid-March, The New York Times ran an opinion series entitled “The Week our Reality Broke” to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the Coronavirus pandemic. For reality to break there has to be a blunt force applied by something else . It has to be something outside the popular conception of what is possible. Something, as Williams says, we could not possibly understand or visualize.

Her interview is part of a collection of oral histories. The video is 6 minutes long and it exists in its corner of the internet, collecting dust the way much of that history has, until this year when the country needed to phone-an-ancestor for some context. The truth is, our reality broke in part because it was brittle; it broke because our culture collectively minimized the historical weight held by the 1918 Flu.

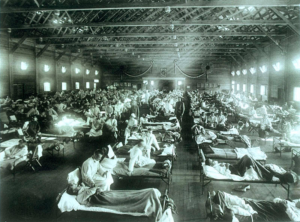

On a global scale, the 1918 Flu was the defining mass casualty event of the early 20th century. Between 50 and 100 million people world-wide died from it, and 675,000 of them were American. That figure is six times greater than the death toll resulting from the concurrent first world war.

The “Spanish Flu,” as it is widely known, was actually quite American. Popular belief places the origins of the pandemic in Haskell, Kansas, a sparsely populated rural county where people lived closely with their livestock. Early in 1918, a local doctor, Loring Miner, noticed a troubling trend in the patients he was diagnosing with influenza. The normal symptoms were more intense than usual — the fevers were impossibly high, the body and headaches were debilitating. More alarming, otherwise healthy patients were dying. He contacted the state department of health but was given no direction. The local newspaper, the Santa Fe Monitor, reported on the outbreak in a matter of fact manner, simply listing the names of county residents who were “quite sick” with “pneumonia”.

Dr. Miner went so far as to warn Public Health Reports, a national medical journal put out by the U.S. Department of Public Health about this “influenza of a severe type.” All the while young men on leave from Camp Funston, a military base farther east in Kansas, were returning home to Haskell County. On March 4, a cook on base reported having common symptoms of influenza. Soon, 1,100 soldiers required hospitalization and an even greater number fell ill. Nearly 40 men died and it is speculated that many of the infected military men carried the disease to other bases around the country. It spread from the bases into civilian communities, both rural and urban, and eventually to the trenches of Europe.

So if the great influenza is American — midwestern, even — why the misnomer? The answer, as with most anything having to do with the 1918 flu, is connected to WWI. Spain, neutral during the war, was one of the only nations not actively censoring its press. With the freedom to report on the tragedies of daily life, Spanish news outlets covered the pandemic internally, creating a paper trail that was largely absent from the early days of the pandemic elsewhere. News spread rapidly when the king himself, Alfonso XIII fell ill.

In the United States, President Woodrow Wilson had passed the Espionage Act a year prior, making it a crime to circulate any information that could “injure” the United States. The postmaster general at the time, Albert S. Burleson, ordered subordinates to report any suspicious materials. By 1918, 74 newspapers had lost mailing rights. That same year The Sedition Act was passed, making it criminal to publish anything that might hinder the war effort. American newspapers became pretty tight-lipped when it came to influenza, especially as Wilson himself declined to mention it. Ever.

John M. Barry, author of The Great Influenza, has emerged this year in the media as a sort of patron saint of 1918 Flu history. In early 2020 Barry gave an interview with CBS Sunday Morning and cited Wilson’s Committee For Public Information as the principal blurrer of the line between fact and fiction in relation to the pandemic. The Committee was headed up by George Creel and sent out press releases that were published verbatim by the nation’s newspapers — on the front page, no less. After a while, editors got the hint and let the sentiments of those releases, “100% Americanism”, as Barry puts it in his book, seep through to the later pages of the paper. Newsmen censored themselves, and thereby lied to the American people. They were assured that this bout of influenza was nothing out of the ordinary, as plain and unthreatening as any other ‘flu’ that had gone around.

“The biggest lesson from the 1918 pandemic is clearly to tell the truth,” Barry later says, explaining that human being’s ability to confront harsh realities is greater than their ability to reckon with the unknown. In the age of modern medicine it is difficult to imagine just how unknown this would have been. But, the confluence of government silence and a lesser developed field of virology created a medical landscape that could do little more for influenza patients than to make them comfortable. There were no antibiotics and no emergency care doctors. The common treatments — enemas, whiskey, and bloodletting — were useless. With training more centered on caring than curing, nurses were uniquely positioned to tend to patients who had little hope of survival. Nurses became so integral to both the war effort and the fight against influenza, in fact, that it is thought their newly minted prominence in American life contributed largely to the subsequent movement for women’s suffrage.

The paradox of a society collectively forgetting something so plainly in it’s rearview is the story of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. The entire episode is so unequivocally tied to amnesia that, since the publishing of Alfred Crosby’s synonymous book in 1990, it has been popularly referred to as “America’s Forgotten Pandemic”. The national government didn’t address it. The newspapers buried it. There was no mass mourning. There was no pause in the dialogue, either during or after, to take stock of the atrocities that had been wrought by disease.

So how did Americans manage? They folded their grief into the accepted narratives of the time — or they kept it to themselves. The losses of the 1918 Flu pandemic were subsumed into the suffering of the war. They had to be. Otherwise the sadness that they brought on would be left to fend for itself, displaced and largely ignored by the culture. In his book, Crosby explains that allowing the wartime death toll to swallow up the fatalities of the flu was, for Americans, “the only way to lend dignity to their battles with disease.”

Death without dignity became common in that era. The nation was hemorrhaging so many young people, if not to the flu than to the war, that there simply wasn’t space to lend distinction to each individual loss. With the pandemic in particular there often wasn’t time for the kinds of end of life rituals one used to make meaning out of death.

Edna Register Boone, who was also interviewed by the Alabama state department of public health, was ten years old when the flu arrived in her small town. Her’s was the only family in town that did not contract it, which placed a great burden on them. “They nursed every family in town,” she says, recalling an instance where her father and uncle dug a communal grave for a family of three. “The people were buried in the clothes they died in and wrapped in the sheets,” Boone says, closing her eyes. She doesn’t remember a single funeral service or church burial. The bodies piled up unceremoniously, and if you loaded a sick patient into a wagon to take them to the doctor, by the time they arrived chances are they would be dead. “That’s why most families just buried their own,” she says.

It was Boone’s job to bring food to the stricken families. Her mother would wrap her head in a gauze bandage so she could drop jars of soup off on the porch safely. One day, she came home to find her mother sprawled out in front of the fireplace. She panicked, she says, and called out to see if her mother had finally fallen ill. Her mother’s response was: “No, child, I’m just so tired.”

The community pulled together because the loss was inescapable, and, whether through war or through disease, it became a constant common denominator. “Lots of times I would come in and I would cry because of all the sickness that was around me,” Boone recalls, “It was depressing to me.”

This is about as much of an assessment as I could find of the mental health consequences of the Influenza pandemic. The vocabulary of trauma was inadequate and problems severe enough to land a patient in a mental ward were seldom connected to the flu. “There was no real language at the time for understanding the losses of the flu pandemic,” says Dr. Esyllt Jones, an author whose book, Influenza 1918: Death, Disease and Struggle in Winnipeg, tracks the changes in familial structure caused by the pandemic in Canada. A lot of “unprocessed grief” emerged from the experience of losing so many people in a short period of time, Jones says. That grief was then compounded by the fact that in many Western Societies, “the memory of influenza was suppressed.”

Without context trauma can grow. Jones says she’s spoken to families who say the absence of recognition and discussion of flu deaths were expressed later in compulsions like alcoholism. “War generates this kind of heroism,” she explains. “Flu doesn’t offer that to anyone so they don’t really have a way to give it voice” she continues, “it must have been isolating for people who had suffered traumas to not be able to speak openly about it.”

“If flu were a disease lodged in folk memory as a subject of terror,” writes Crosby, “then people would have recalled and discussed such an emotional experience for generations to come.”

The New York Times ran infrequent influenza coverage, and those stories tended to be confined to short, one-off pieces about business closures or local outbreaks. A cursory glance of the newspapers from that time would give no indication that influenza was indeed the most formidable threat to the American people. On December 20th of 1918, a short article relegated to the 24th page of the issue reported that 3 million people had died worldwide from the flu. It would seem that this would be a front page affair. The Times’ medical correspondent out of London wrote that the numbers indicated influenza was five times deadlier than war. “Never since the black death has such a plague swept over the world,” he wrote.

Some historians argue that given the prevalence of disease, and lack of modern medicine, Americans might simply have been less shaken by the whole ordeal. After all, 110,000 people died of Tuberculosis in 1917. Life expectancy at birth hovered in the early 50s. The logic is that death was less of a stranger to people in 1918, therefore their capacity to be shocked by it was dulled. The contrast was one of degree, not kind.

Others, like Professor Nancy Bristow, argue that the trauma caused by death is not an emotion that fluctuates with the time period. “People are saddened by loss in any generation” she says, “and the fact that they had a higher infant mortality rate, or they had a shorter life expectancy, doesn’t change the fact that the pandemic in 1918” destabilized their society.

Bristow says it was a much more private society. Today we document our every move via social media, she argues, we talk about ourselves and our feelings. In 1918, that kind of openness outside one’s family or close friends would have been abnormal. “I’m more forgiving of the way that they didn’t listen to the trauma or talk about the trauma in the aftermath,” Bristow says, “because it would have been really quite revolutionary for them to have responded in any other way.”

She writes in her own book, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic that a historical storyline tainted by grief did not fit in with “Americans’ sense of themselves.” Personal stories of grief still existed, they just didn’t dare enter into the public sphere. Bristown makes an important distinction between public and private memory. That is to say — America may not have remembered the 1918 Flu, but Americans certainly did.

Bristow’s grandfather was 14 at the time of the pandemic, and lost both of his parents in the span of four days. That kind of orphaning was common. The mortality curve for this particular influenza, in contrast to any normal strain, was concentrated between the ages of 20 and 40. This disease killed people in the prime of their lives , people with children not yet old enough to look after themselves, and people who by today’s standards were children themselves.

In the 1919 Yearbook for Montana State College, the Montanan, a young man’s diary is published, with an excerpt that reads, “No more dates. The girls at the dorm are all quarantined — no influenza there and they think they can keep it out by locking themselves in.” The entry is dated October 21st–smack-dab in the center of the deadliest month ever recorded in American history. Youth did not pause and wait for the 1918 Flu to pass before it could once again swoon over the flippy haired coed who lived across campus. And all the while their experiences were not halted but informed by the presence of a silent enemy that killed 195,000 in October alone. “Spanish Influenza had a permanent influence not on the collectives but on the atoms of human society” writes Crosby, “the individuals.”

The 1918 flu might have been painful for people to remember, but Bristow argues that it was more painful to be forced to forget it. “Processing one’s trauma, talking about it and being heard, having people listen to you and believe you and affirm you is part of how you go on to have a life that works” she says. There may not have been explicit reference to phenomena of mass loneliness or bereavement but the sense that something was off, especially for the young people, was ever present. “People have described this as living walking alongside the dead for that generation” Jones tells me, “this kind of presence that nobody really was encouraged to discuss or think about.”

America seemed to place processing at the bottom of the list of post-pandemic priorities. Encouraged by a political sector eager to revel in the triumph of the war, and the economic prosperity of the mid-twenties, the Flu was scratched from collective memory. A rhetoric of optimism and ingenuity sprang up, particularly in the public health sector. “They relegated the pandemic to an increasingly irrelevant past,” writes Bristow, “leaving little room for the retention of public memories of it’s real costs.” A similar bright-eyed, all steam ahead approach was taken in the work of journalists, the Red Cross, and even government itself; congress challenged appropriations for research in epidemiology only a few years after the pandemic had ended.

Susan Kent, author of The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919, says “the lost generation,” which is a popular moniker for the cohort of Americans emerging from the war, and among which Hemingway is often placed, was likely not “lost” for the reason we think. “They experienced a sense of themselves as having been betrayed by their elders, a sense of the futility of life, questioning about the notion of civilization” Kent explains. Though history often attributes this cynicism to the war, the flu would have had a much more tangible and immediate effect for most of the population. They weren’t just “lost” in spirit, she says, they got their name because of the number of them who really were just missing. It was as much a generation made up of phantoms as it was of the living — and those living must have been haunted by the dead. The processing power just wasn’t there.

“We have opportunities that would have been very hard to have accomplished in 1918, but sit there just for the taking in 2021.” Bristow explains, “Which is to say: we shouldn’t forget about this.”

Army of Ghosts: The AIDS Epidemic and the Power of Activism as a Grieving Rite

“If it’s really a plague, you live with it for the rest of your life” Jim Eigo tells me one Wednesday afternoon. He has invited me, albeit virtually, into his East Village kitchen, where we talk for an hour about the myth of “processed” grief, and the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York City.

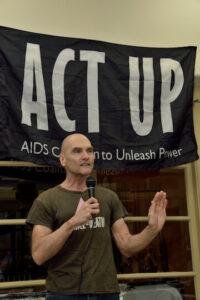

Eigo is a writer and activist, whose work with ACT UP — a grassroots organization founded by activist Larry Kramer in 1987 to fight the AIDS epidemic — helped accelerate the discovery and approval process of life-saving drug cocktails. He is also one of the subjects of the award-winning 2012 documentary “How to Survive a Plague.”

“At the beginning, it was positively medieval” Eigo says, “we only knew some gay guys were getting sick, losing huge amounts of weight, having awful lesions and then coughing their lungs up and dying.” What they didn’t know though, was why it was happening. Because they presented themselves so painfully and clearly, the symptoms marked the start of the epidemic, before the disease itself was understood. Eigo says it became apparent early on that whatever the disease was it must be sexually transmitted, given the volume of gay men who were falling ill. It would be years, however, before HIV was isolated as the single causative agent.

“When it was finally discovered I saved the picture of Science magazine,” Eigo recollects, “it’s diabolically gorgeous.” He uses the word diabolical because of what the virus does, he says. It hijacks the immune system and turns it into a factory for itself before releasing more and more copies into the bloodstream. It goes into the brain, the gut, the heart — and then it stays there for good.

This may be well known now, but at the epidemic’s start in 1981, the disease was surrounded by such a shroud of mystery and stigma, it got branded in the media simply as “Gay Cancer” or, worse, “The Gay Plague.”

“Death was riding a horse, you know, on your horizon line” Eigo tells me, “That’s what it felt like, because you didn’t know what it was and where it would strike next, and it just kept getting bigger and bigger.”

A pattern started to emerge in 1981. Previously healthy gay men began exhibiting one of two conditions — a rare lung infection known as PCP, or a fast-moving cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma, that showed up on the skin in the form of purple lesions. It wasn’t until September of 1982 that the CDC first used the term AIDS, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, to describe the condition wreaking havoc on gay communities across the country, notably those concentrated in New York and California. There were 853 reported deaths of AIDS that year.

A month after the CDC gave the disease a name, journalist Lester Kinsolving brought it up at a White House press briefing. “Does the president have any reaction to the announcement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta that A-I-D-S is now an epidemic?” The recording hears press secretary Larry Speakes rustling papers and mumbling about not having anything on A-I-D-S until Kinsolving speaks up to clarify. “ It’s known as gay plague” he says. There’s a moment’s pause and then Speakes quips back “I don’t have it, do you?” and the whole room erupts in laughter.

There was a certain callousness in talking about the epidemic that both the media and government deemed permissible at that time, and Eigo argues it had everything to do with the kinds of communities it was affecting. “It was only by ’87 when finally enough people realized that it’s not just a healthcare crisis, it’s a political crisis too” he says. “They are letting faggots and drug addicts die because they don’t give a hoot about us.”

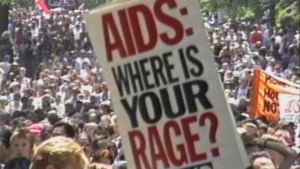

By 1984 5,000 people had died of AIDS in the United States, and again Kinsolving brought it up in the press room. This time, Speakes responded more somberly, “I haven’t heard him express concern,” referring to the president. By the end of 1985, the death toll had risen to over 12,000 in the U.S. In late September of that year Reagan used the term AIDS for the first time publicly. It is oft noted that that was the same year 13-year old Ryan White, a hemophiliac from Indiana who contracted the virus from a blood transfusion, sparked national hysteria with his diagnosis. Suddenly the epidemic had claimed a victim whose personhood couldn’t easily be mocked by the White House press pool.

The national headlines may have been scrubbed of the AIDS crisis, but on the ground, for members of the communities most affected, the reality of a targeted and cruel plague was playing out daily. “People were quite literally dropping in the streets in the first several years” Eigo says, “we, even those of us who were activists, were just trying to comfort our sick.” Here he pauses and exhales roughly. I can tell even over Zoom that he is giving himself a moment’s grace so he does not cry. It sharpens the point he is about to make, “… make sure they had roofs and medicines,” he continues, “and burying our dead.”

The plague eclipsed everything, he says, and it became clear that if something was not done to signal a sense of emergency to those in power, there wouldn’t be much community left. Here was a disease that was draining human life from an already marginalized cohort of people, and the country was carrying on without a care. “AIDS ripped back the covering on so many issues,” says Mark Milano, another veteran of ACT UP. “It hit gay people more than straight people. It hit people of color more than whites. It hit poor people more than rich people. It hit developing nations more than first-world nations. It hit drug users more than non drug users. Literally, it was like a virus that targeted every oppressed community in the world,” he says.

The medical establishment was moving forward with research and eventually the development of drug therapies, but not at a pace that matched the urgency of the moment, many felt. The drug approval process being used by the FDA took over five years and the federal government was not applying much pressure. The popular perception among activists and those affected was that the system dragged its feet because the kinds of lives that AIDS was taking were perceived as disposable.

ACT UP grew largely out of an anger at that apathy. “We in the streets, we were putting our bodies on the line because gay bodies and the bodies of injection drug users and their partners had become the site for a social struggle” Eigo explains. It wasn’t just the severity of the epidemic that prompted organized action, it was also the timing. The gay liberation movement had reached fever pitch only a few years prior. “We suddenly had created a community that was vibrant and living,” Milano says. “You could breathe, you know, and then the eighties took all that away. Suddenly we all were dying and nobody gave a fuck.”

It is common among survivors and activists to compare the AIDS crisis to a war. Warfare of course implies not only the clash of two forces, but also the inevitability of mass casualty. Larry Kramer, the founder of ACT UP, can be heard in footage from How To Survive a Plague characterizing the way the community was being hollowed out, saying, “People die everyday, friends get sick everyday, it’s like being in the trenches.”

“The big thing in Act Up was you take your grief and you turn it into anger,” Milano says, “Every time somebody died, I recommitted myself to the battle and I decided I’m gonna fight even harder in the memory of this person that I’ve lost.” It is unsurprising given this philosophy the force and anger with which ACT UP took to the streets. Their power was compounded hundreds of times over by each loss, and there were so many losses. “Those of us who were activists were busily accruing new friends and colleagues only to have them die,” Eigo reflects, “we lost a huge portion of my generation.”

For some who lived through the AIDS crisis, the coronavirus pandemic has conjured painful flashbacks of the casual cruelty with which those without power are treated. For Eigo it was the unceremonious handling of senior citizen deaths in nursing homes during the early days of the outbreak. The expendability felt familiar. “They’re just throwing our bodies out like so much trash,” he says. For Milano it was those pangs came from an unlikely place. The “feel-good” stories at the beginning of the pandemic, of retired physicians and nurses suiting up to join the fight burned a little bit, he says. They’ll risk their lives for someone like them, but nearly four decades ago it was a different story. “In the eighties we were subhuman. We were faggots and junkies and we were not innocent victims,” Milano explains. “So every time I hear the story of somebody risking their lives to help now, it’s wonderful, but it also hurts because I remember how we were treated.”

Kate Barnhart started attending ACT UP meetings when she was just 15 years old. “My mom had fought the Vietnam war and always talked about that as sort of the threat to her generation: being drafted,” Barnhart explains. “It just really felt like AIDS was our generation’s war.” Those were her formative years, and ACT up essentially raised her. They took her activism seriously, despite her age, and welcomed her into the fight — a battle she’s still waging. Even though AIDS is now considered a treatable condition, the war is far from over. She works now with LGBTQ homeless youth, through her organization New Alternatives, and she told me there was one young man in her program who would likely die from AIDS within the week. “At the intersections of poverty and homelessness and mental illness and drug use there are still people getting sick and dying, and that’s just not part of the narrative” Barnhart explains.

Milano says his work as an AIDS educator has illuminated another aspect of the war yet to be won — de-stigmatization. “If an HIV negative man, wants to ask your HIV status because you might have sex. Right. Do you know how they ask the question?” he asks me. I hesitate and he fills in some acceptable answers “Do you have HIV?”, “Are you HIV negative?” That’s never the way they ask it, he says, what they ask is: “Are you clean?” “Can you imagine a more stigmatizing way to ask that question?” Milano implores, “What am I supposed to say? No, I’m diseased. I’m filthy.”

That vocabulary is not new. It is a tragic side-effect of the kinds of attacks levied against those diagnosed in the early days of the epidemic, and the potency of that stigma remained all throughout, legitimizing in the eyes of many the slow and minimal response of the government. In 1987, 40,000 Americans died from AIDS. “When it comes to preventing AIDS,” asked Raegan in an address, “don`t medicine and morality teach the same lessons?”

The president’s words are a very thinly disguised rebuke of homosexuality. If one were behaving “morally”, he says, they would not be at risk for contracting the virus. As a community was grieving over its fallen, the most powerful voice in the country was implying that there was a moral justification for those losses.

“It was basic prejudice that killed people” John Callari says. Callari worked in television advertising in New York City during the eighties and says that though he never contracted HIV, as a gay man living in the city at that time, it was never more than an arms length away. Though not an official member of ACT UP, he often attended the protests. “The deaths I thought fell directly at the foot of the government and the politicians that didn’t care enough to do anything,” he says, “It was one trauma after another, after another, as these people got sick and died. And most people that got sick did die.”

It wasn’t just the volume of the loss, it was the way that it happened too. “Let’s just say people didn’t linger,” he tells me. The process, especially at that time when hospitals were overwhelmed and no effective drug treatment had been approved, was incredibly quick. “It was sort of like being in a war,” Callari muses. He says he had one friend who died only a week after he discovered he was sick. Another didn’t want people to see the physical deterioration that the disease had wrought, so didn’t allow visitors. Rapid weight loss was common among AIDS patients, and those with severe Kaposi’s Sarcoma often had tremendous amounts of purple lesions on the skin.

“It was the sweetest, most beautiful people who went first,” Milano says, “and assholes like me seemed to survive forever.” He was diagnosed in 1982 at the age of 26. I ask him how he endured the loss and the proximity to death. He explains that he became good at holding two opposing thoughts in his mind at once. He was both sure that he would never die of AIDS, and sure that there was a good chance he would. He says that the legacy of ACT UP, the power of a collective to take charge of its own gave him something to be proud of. “That’s the place where I really felt like I was part of a group of warriors,” he reflects.

Eigo calls AIDS “a quick teacher.” Activists had to educate themselves to understand the science behind the disease. “We became pseudo doctors because we had to,” he says. “All of us had to discover talents we never knew we had because the body count was so high.” That need to work outside of the system continued in the post-Reagan era. His successor, the first President Bush, stood by a travel ban that barred people with AIDS from immigrating permanently to the United States or entering outright. The hard won entry into the rooms where medical priorities were being decided was not a battle fought under the freedom to petition your government. ACT UP didn’t wait for the system to hear them out, it bullied its way in through targeted and dramatic demonstrations, because the kind of anger that had been sewn over a decade of neglect wouldn’t wait for the wheels of bureaucracy to turn. By 1996, when a successful cocktail of drugs was finally found to treat AIDS, the community had already been decimated.

In gay culture, Callari tells me, it is not uncommon for your friends to become your family. And this family learned to mend itself, and to dignify the struggle with radical love and, by virtue of that love, radical action. “It was heartbreaking of course, to see people sick and dying” Ann Northrop, a former journalist and founding member of ACT UP says. “But there was also a lot of joy in the room, and a lot of humor and sex and camaraderie because we were joined together so closely working on something so fundamentally important; life or death issues.”

The bonds of war never leave it seems, and neither do the spirits who were lost to the battle. “There’s still such a reservoir of sorrow for everything you lost, for everyone you lost” Eigo says. He says any talk of heroism or winning is almost obscene, because so many people died before treatment was found. “You hear so much about processing grief and I’ve never liked that term” he says, assuring me that he isn’t silly enough to think the trauma of those years will ever leave him, or that it should. The grief is a mere bargaining chip used with the powers that be in exchange for the memories of souls lost. “I am in the same place I was during the AIDS years” Eigo explains, “so I walk the streets and the ghosts walk with me.”

It’s not an unwelcome company though. To look at one’s grief and to find ways to live with it still stored in the pockets of your being is so much wiser, Eigo says. The residual grief is a price easily paid he thinks for living in a city still populated by the memories of those who have passed. “Part of me does not want that to change,” he reflects, “because I don’t want to lose those people.”

Callari holds a similar preservationist view. “Through photographs, memory, objects, whatever,” he says, “I’ve kept them alive in my psyche, almost all of them, you know, because they’ve all meant so much to me.”