Part 1: Setting the Stage

Han Han stands backstage at the Lula Lounge, puffing up the butterfly sleeves on her inabel dress one last time before her performance begins. It’s January 30, 2020, and the 35-year-old Filipina Canadian rapper is debuting her sophomore album “Urduja” at one of Toronto’s premier clubs.

As she walks onto the stage, her beaded T’boli belt, cinched around her waist, jingles with each step. The belt is one of the many pieces she’s commissioned from Filipina artisans to pay homage to her culture.

Raising the microphone to her lips, her brass bangles ― purchased from women merchants in Lake Sebu, South Cotabato ― shine under the stage lights. Han Han visited the municipality after the release of her first album to donate the sales to an indigenous school, Lake Sebu School of Living Traditions.

She greets the audience as her backing band begins to play “Mandirigma,” the first song off her second album. The LP ― just like Han Han’s first release ― is rapped almost entirely in Tagalog and Cebuano, with English words sprinkled onto a production blend of 808 beats and Filipino rhythms.

Named after a warrior princess in Filipino folklore, “Urduja” encapsulates the emcee’s essence: strong, feminine, and multicultural. As an Asian woman in an industry dominated by Black men, Han Han thinks that the best way to fit in is to stand out.

“I feel like an outsider. I have always felt like an outsider. My music is in Filipino languages and I am based in Toronto. I’m a rare breed,” Han Han says to me. “However, I understand the value of my work and refuse to conform to the stereotype of what a hip-hop artist should be or what the hip-hop industry as a commercial machine demands.”

Han Han is part of a growing group of “outsiders” making waves in the industry. As an intrinsically political space, hip-hop has long existed as a sort of sanctuary for marginalized communities. But women, especially Asian American women, still constitute a small fraction of the genre’s talent.

By embracing her heritage and gender, Han Han ― and Asian American women rappers like her ― are attempting to disrupt the hip-hop industry. But do they feel as though they belong?

![]()

Part 1.5: A Brief Hip-Hop History

In the Bronx, circa the 1970s, hip-hop is an underground movement, growing from Black New Yorkers’ block parties. Characterized by rapping, DJing, b-boying, and graffiti, the genre paves its own path while simultaneously paying homage to earlier Black-rooted music through sampling.

40-something years and the proliferation of music streaming services later, hip-hop has evolved into one of the most successful, marketable, and profitable industries of all time.

As hip-hop continues to rise in popularity, so too have non-Black hip-hop artists. A historically Black genre, hip-hop now houses a steadily growing crowd of non-Black artists, especially Asian American artists.

In 1984, Fresh Kid Ice, Luke Campbell, Mr. Mixx, and Brother Marquis formed the hip-hop group 2 Live Crew. Notorious for their unapologetically sexual lyrics, the quartet shocked, disturbed, and ultimately captivated massive crowds through the late ‘80s and early ‘90s with songs like “Me So Horny” and “We Want Some Pussy.” In addition to the revolutionary nature of their obscenity, the group made history by putting Asian American rappers on the map.

Recognized as the first notable Asian American rapper, Fresh Kid Ice embraced his Trinidadian Chinese heritage, especially when venturing into solo projects like “The Chinaman” and “Freaky Chinese.” Fresh Kid Ice remains legendary not only as one of the first Asian American rappers, but also as one of the first Asian American sex symbols. His very presence in the industry subverted stereotypes surrounding Asian masculinity and set the stage for Asian Americans in hip-hop.

Although hip-hop remained largely dominated by Black talent, the early ‘90s provided a platform for Asian American rappers, like Filipino American turntablists DJ Qbert and Mix Master Mike, Filipino American rapper apl.de.ap of Black Eyed Peas fame, and Chinese American hip-hop group Mountain Brothers. The early aughts saw the rise of Chinese American rapper MC Jin and Korean American rapper Kero One. And the last 10 years introduced Indian American rapper Heems from Das Racist, Black Filipina-Chinese American rapper Saweetie, and the wildly popular Asian American hip-hop collective 88rising.

Despite the growing success of Asian American artists in the industry, many emcees exist in a sort of limbo ― feeling simultaneously too Asian and not Asian enough. As a result, artists often cleave their identities in an attempt to appease two demos with polarizing demands. The Mountain Brothers actively divided their content into two disparate promotional packages for their Asian and non-Asian fans, explicitly referencing their Chinese American heritage when appealing to the former and intentionally concealing their heritage for the latter. Similarly, MC Jin bisects his fanbase into separate Asian and non-Asian factions by assigning the groups different names.

How then do Asian American artists manage this sense of segmentation? And how does this bifurcation reflect broader themes of Asian American belongingness within society at large?

![]()

Part 2: The Pursuit of Being “Fucking Empowering”

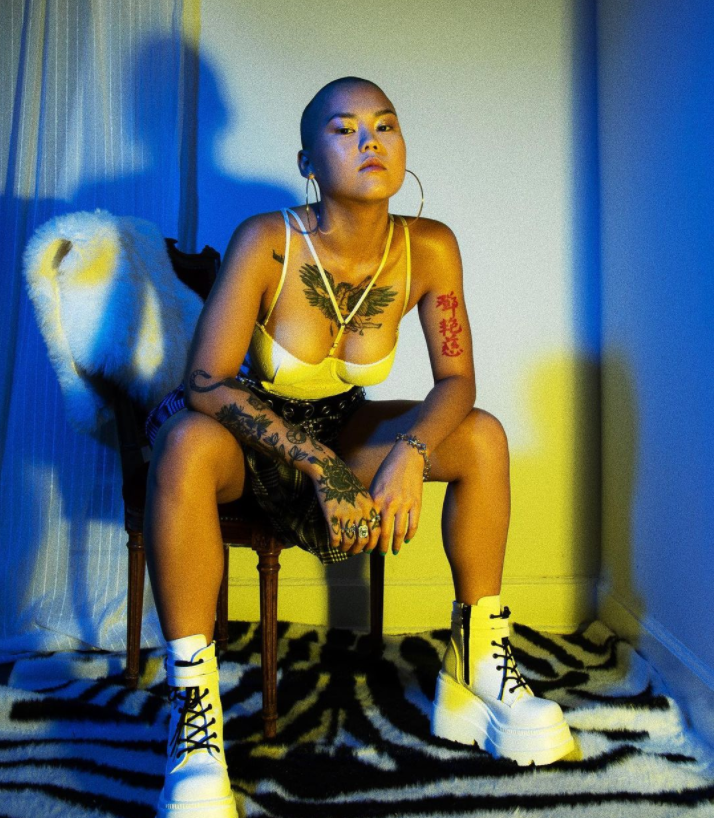

When Chloe Tang walks into a studio with her boyfriend, people assume he’s the rapper and she’s the girlfriend. Literally covered in tattoos from her head to her toes, the 25-year-old Chinese American artist makes an impression, but as a woman in the male-dominated world of hip-hop, she’s immediately codified as an accessory.

“It sucks, but all I can do is be a good example of a strong woman in the industry and support other women and marginalized communities who are working their asses off,” Chloe says to me. “That’s why representation is so important ― media and music are so influential in pop culture so when people see parts of themselves in the artists, it’s fucking empowering and that creates change.”

She’s one of the many hip-hop “outsiders” finding solace and strength in her otherness, like Filipina American rapper Ruby Ibarra who entered the industry beset by concerns of looking, sounding, and being too different. The 30-year-old California native compensates for her petite stature with a larger than life smile. Like Han Han, she raps in two Filipino languages ― Tagalog and Waray ― as well as English.

10 years later, Ruby recognizes that her otherness helps her success, not hinders it. “I realized that my difference is what makes my music and my lyrics unique ― knowing that no other artist out there will sound like me or have exactly the same story as me.”

Ultimately, Ruby sees her experience as an Asian American woman in hip-hop as one of “privilege” because her otherness categorizes her as intrinsically more visible. Through acknowledging her privilege, she maintains a sense of gratitude for the Black artists who not only laid the groundwork for the industry, but also welcomed her into it.

Ruby, Chloe, and Han Han collectively navigate through the world of hip-hop with an unwavering understanding that Black artists are the originators and prevailing talent of the genre.

“As a non-Black artist, I am very aware of my position,” Han Han says, “Hence, I always make sure that I don’t perform Black, I perform Filipina.”

Han Han’s considered celebration of her culture through her lyrics, beats, and clothes reflects her desire to “give hip-hop a uniquely Filipina flavor,” rather than appropriate Black culture.

Likewise, Ruby says to me, “I want to always be certain that I’m respectful to both the genre and the culture in how I perform and what I talk about ― this is why I value the importance of authenticity; I want to make sure that my lyrics will always reflect reality and that I am authentic in my voice and experiences.”

The artists approach the industry by actively acknowledging the distinction between cultural appreciation and cultural appropriation. For instance, non-Indian people can appreciate Indian culture by buying art from an Indian creator, but would be appropriating Indian culture by wearing a bindi with no regard for the long, significant cultural history of the tradition.

“Appropriation is taking someone’s culture and claiming it as your own,” Chloe says, “we can all celebrate our own cultures and other peoples’ cultures in a respectful way but the most important thing is listening to only Black voices when it comes to their culture.”

Han Han adds, “cultural appropriation happens when there is lack of acknowledgement of the originators and lack of respect which can be shown when you perform Black.”

Embracing their identities as Asian American women, Han Han, Chloe, and Ruby create a sense of belonging for themselves without stealing from Black artists.

“I believe my place as an artist is just setting an example of being an ally to current Black creators while creating music that is true to me; that means listening to Black voices, listening to Black-created music, and asking questions,” Chloe says, “Because in the end, it’s not about me or any single artist. This industry is about collaboration, compassion, and appreciating other creators ― past and present.”

![]()

Part 3: The Ornithology and Methodology of the Culture Vulture

Culture vultures are as endemic to hip-hop as pigeons are to New York. When many non-Black artists fly into the industry, they prey upon Black culture, scavenging for a look and sound to claim as their own as they attempt to flesh out their identities.

Perched at the top of the culture vulture pecking order is Awkwafina, the Chinese Korean American rapper/actress whose career has skyrocketed to international success.

Bursting onto the scene in 2012 with “My Vag,” Awkwafina introduces herself and her blaccent, a feature which we now recognize as quintessential to her brand. Awkwafina raps in AAVE (African American Vernacular English) on bars like “My vag, a Beyoncé weave / Yo vag, a polyester Kmart hairpiece.”

The blaccent exists as one of the most cherished relics for culture vultures as they convince themselves that modulating their voices will earn them street cred. Non-Black artists not only forsake their own identities through their attempts to “speak Black,” they also reduce Blackness to a caricature akin to minstrel shows.

When Awkwafina began her foray into acting with “Crazy Rich Asians,” she was simultaneously cast as the character of Peik Lin and the caricature of the sassy Black friend. Her blaccent and reliance on Black stereotypes continue on full display in “Ocean’s 8” where she plays a “version of herself: a scrappy, die-hard hustler from Queens.”

Speaking of her New York background, Awkwafina’s defenders insist that her performance of Blackness reflects her multicultural upbringing in Forest Hills. But if that’s the case, where are the Black people in her semi-autobiographical show “Awkwafina Is Nora from Queens?” And while Queens may be the most ethnically diverse borough, Forest Hills’s majority white and Asian population suggests Awkwafina’s blaccent is far from organic.

With that being said, the long standing relationship between Awkwafina and her blaccent may be on the rocks. The actress landed her first leading role in 2019’s “The Farewell,” a dramedy about familial death. The darker, more serious material provided us with our introduction to Awkwafina’s real accent since her caricature of Blackness is reserved for laughs.

While Awkwafina’s break-up with her blaccent earned her the Golden Globe for Best Actress, it cemented that, to her, Blackness is a role which can be appropriated when convenient. Unlike Awkwafina, Black people can’t “turn off” their Blackness. The stolen, exaggerated mannerisms that she profits from can cost a Black person their job or their life.

As vocal as culture vultures are in their performance of Blackness, they often opt for silence in their reactions to anti-Black racism. Beyond a general lack of non-Black commentary on structural inequality, many non-Black hip-hop musicians failed to throw any semblance of support behind the Black community in the wake of George Floyd’s murder.

Black culture matters to culture vultures, but Black lives seem to be of less importance. Even as the Black Lives Matter movement continues to grow, many of the most prominent non-Black hip-hop artists make no statements with their mouths or their wallets.

The biggest Asian American hip-hop group, 88rising, only donated money in response to mass criticism. And the $60,000 that the group collectively coughed up pales in comparison to the $120,000 that many of the members charge for individual performances.

Chinese American rapper Bohan Phoenix urged 88rising to use their platform for good, writing on Instagram, “Not only is 88 profitable but it’s also very influential in Asia, where people have little context of the complex racial struggle that birthed hip-hop in the first place, or understand the concept of white supremacy and systematic racism that’s behind the atrocities today. You have the resources and responsibility to start this education. Lead by example and stop spreading ‘hip-hop culture’ without showing the proper respect and acknowledgement for the communities that suffered to create it.”

While 88rising posted a general note on Instagram, pledging to “raise our voices for equality everywhere,” they failed to post on Weibo, China’s primary social media platform. Sites like Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook are blocked in China, nullifying the influence of 88rising’s call to action in a country whose residents share a particularly complicated relationship with hip-hop.

Once a largely underground genre, hip-hop rose to sudden popularity among Chinese audiences in 2017 with the premiere of reality competition show “The Rap of China.” After amassing over one billion views in a month of its release, the series has been credited not only with making hip-hop mainstream in China, but also with introducing the genre to an entire country.

With that being said, the show presents hip-hop in its most superficial form. Quite literally all glitz and glam, “The Rap of China” employs hip-hop iconography, like awarding chains as indicators of contestants’ success, without addressing the genre’s cultural and political roots.

Speaking to Variety, Bohan says, “They completely sanitized it. There wasn’t a single episode talking about the origin of hip-hop. There are Chinese kids effectively seeing dreads on Asian kids for the first time. There’s Chinese kids listening to hip-hop for the first time from Chinese people.”

“The Rap of China” thus introduces hip-hop in a silo to an already siloed country. Many of the show’s former contestants ― when criticized by non-Chinese hip-hop fans ― admit they know nothing about the genre’s Black origins, like Sun Bayi who said, “I know racism in theory, but it’s hard to empathize with it.”

Despite owing their careers to Black artists, many Chinese rappers either refuse to acknowledge hip-hop’s Black history or attempt to villainize it. Kris Wu, one of the judges on “The Rap of China,” avoided posting about Black Lives Matter for his 50 million Weibo followers. At the other end of the speaking spectrum, “The Rap of China” winner PG One blamed the influence of Black music when his lascivious lyrics came under fire.

For Asian American artists like 88rising, with one foot in China and the other in the US, filling the gaps created by “The Rap of China” and the country’s subsequent hip-hop culture perhaps seems intuitive. That’s not to suggest that educating the Chinese populace rests on the shoulders of 88rising, but considering their colossal clout, their silence feels a bit deafening.

Taiwanese Canadian rapper Malasung even suggests that 88rising isn’t hip-hop, saying, “Hip-hop is all about freedom of speech and freedom of expression. If you don’t have that, then it’s propagation.” The fundamental censorship in China complicates this notion of freedom, but 88rising maintains a notable level of popularity in more open countries, like the US.

Similarly, when speaking to Variety, Chinese rapper Dawei criticizes 88rising’s purposefully apolitical messaging as “completely anti-thinking, anti-social-involvement, anti-any kind of historical reflection,” selling listeners a “total consumerist” experience. He says, “When you listen to their music, you don’t think about any issues related to the socioeconomic environment or anyone else’s life, the only takeaway is you feel ‘cooler’ ― it’s like putting on gold teeth or jewelry.”

While 88rising bears no responsibility to rebrand as an actively political group, their effort to wholly divorce themselves from politics is inherently anti-hip-hop, as Malasung argues. Besides the fact that hip-hop has always existed as a powerful means of liberation for marginalized communities, the very nature of performing as an oppressed person is political. When a woman or a Black person or an Asian person or a queer person holds a microphone, every sound that comes out of their mouth is political because their existence is political. Therefore, 88rising’s aversion to politicization does a disservice to both hip-hop and themselves.

88rising’s biggest star, Rich Brian, began his career under the name Rich Chigga, a portmanteau of “Chinese” and the racial slur that also appears in the lyrics of his early songs. Despite years of backlash, Rich Brian only changed his name when he decided it was “corny.”

Potentially nefarious motives aside, why do so many non-Black Asian artists feel such a connection to a word which was never theirs to claim? The broader scope of American mass media may hold the answer.

As the population of Asian American people in the US continues to rise, Asian American representation remains dismal. While recent books and films like “To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before” and “Crazy Rich Asians” sparked a shift towards spotlighting Asian American talent, Hollywood still largely overlooks Asian American actors and Asian American stories.

According to the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, of the 1,300 top-grossing films made between 2007 and 2019, only 3.3% of directors were Asian/Asian American and only 0.002% were Asian/Asian American women. Of the top 100 films made in 2019, 55 failed to include Asian/Asian American women/girls on screen.

The few movies that feature Asian/Asian American women often relegate them to two tropes: the lotus blossom or the dragon lady. Coined by Asian American studies scholar and Oscar-nominated filmmaker Renee Tajima-Peña in her essay “Lotus Blossoms Don’t Bleed: Images of Asian Women,” the dichotomy paints Asian women as submissive, compliant sex objects or evil, threatening sex objects. Both tropes reduce Asian women to their sexuality and frame Asian women characters as relevant insofar as they sexually gratify their male counterparts.

With hardly any relatable depictions on screen, many Asian American people gravitate towards the visibility of Black culture to supplement the invisibility of Asian American culture. In his analysis of anti-Blackness in South Asian communities, Indian Canadian journalist Dhruva Balram writes, “We grow up thinking we are Black, happy to exploit the culture and co-opt its identity for our own capital and cultural gain. Yet, in doing so, we negate the lived experience of being Black. Not to mention the specific, inherited, cross-generational trauma that comes with it. We do not feel accurately represented in the mainstream and so we position ourselves closer to Black cultures ― or rather the packaged version marketed to us ― in an attempt to feel something that always seems familiar but is an arm’s length away.”

In a society where whiteness is the default, non-Black Asian and Latino Americans often seek out the “other” as a means of subverting white supremacy. Being that race is constructed in the US as a literal Black and white issue, the “other” thus corresponds to Blackness.

Ariana Valle, a Latino Studies professor at NYU, says, “In the US, we view race through the Black-white binary paradigm, or the Black-white continuum, which places Black people on one end of the spectrum and white people on the other. Because of their respective skin color, Latino people are placed on the end closer towards Black people and Asian people are placed on the end closer to white people.”

Upon intentionally positioning themselves close to Blackness, many Asian Americans add the n-word to their lexicon. Through subconscious appropriation or a deliberate desire to equate the oppression of Asian Americans with that of Black Americans, the n-word permeates Asian American youth. Bangladeshi American rapper Big Baby Gandhi recounts saying the n-word as “mad common” when growing up in New York as does Indian Canadian rapper NAV who blames his multicultural neighborhood for his use of the n-word.

The lens of whiteness through which many Asian American characters are conceived frames Asian American women as hypersexual and Asian American men as sexless. When emasculated stereotypes like “The Big Bang Theory’s” Raj dominate Asian American representation, the “coolness” of Black culture becomes aspirational.

Thus, the process of becoming a culture vulture is often inadvertent and sans malice. Rather, appropriating Black culture acts as an unconscious method of gaining acceptance, validation, and identity.

The deficit of Asian American media representation explains how glaringly appropriative performers like Awkwafina can find widespread success. She might have built her career on the backs of Black women, but to people seeking representation at any cost, the ends justify the means. Awkwafina may treat Blackness like a performance, but she’s also the first Asian American to win the Golden Globe for best actress. So how do we grapple with celebrating representation at the expense of brazen cultural appropriation? By rewarding Awkwafina for her minstrelsy, are we further exacerbating tensions between Black Americans and Asian Americans?

![]()

Part 4: Contextualizing the Conversation

For many people ― especially the aesthetics-obsessed among us ― trips to the nail salon occupy a significant place in our hearts (and bank accounts). The ever-familiar fluorescent lights and orchestral music reinvigorate our minds, just as our technicians reinvigorate our nails.

When I sit across from my nail tech every three weeks, I become a life size doll. She holds my hands in hers, with the delicacy typically reserved for an infant, before carefully sweeping my hair off my shoulders as if each of my black curls is made of gold during her complimentary massage.

While women who look like me pay for the bona fide Barbie experience, many others are not afforded the same luxury on the basis of their appearance. When Black women step into non-Black-owned salons ― namely Asian salons ― they contend with microaggressions and, occasionally, harassment. Asking for extra-long acrylic nails not only comes at the cost of $150 or so, but also at the cost of techs’ sneers, eyerolls, and lamentations of, “You would really look better with shorter nails.”

In salons throughout New York, it’s not uncommon for Korean manicurists to reserve their complimentary massages for non-Black clientele. Techs often respond to Black women chatting among themselves with pursed lips and raised eyebrows.

At times, these microaggressions evolve into violence. In 2018, New Red Apple Nails in East Flatbush provided the backdrop for a viral brawl. When Christina Thomas refused to pay for an eyebrow waxing she judged unsatisfactory, the staff attacked Thomas and her sister and grandmother, beating the three Black women with broomsticks, dustpans, and their fists.

The altercation reflects a larger phenomenon of Asian-perpetrated racism against Black women in supposedly safe spaces.

In 2017, Charlotte, North Carolina resident Nancy Wilson posted a video to Facebook of Missha Beauty’s manager Sung Ho Lim shoving, kicking, and wrestling a customer to the ground in an attack which culminated in a 30-second-long chokehold.

Lim assumed the customer ― an unidentified Black woman ― was attempting to shoplift, even as she repeatedly denied his accusation and suggested that he look inside her bag.

The episode not only exemplifies the phenomenon of Asian-Black violence, but also the recurring trend of Asian-Black violence at Asian-run stores that cater to largely Black clientele. Korean-owned Missha Beauty is one of many speciality shops offering hair and beauty products for Black women which are notoriously difficult to procure in drugstores.

Speaking to this phenomenon, Twitter user Jasmine Jessie writes, “It infuriates me that there are so many Asian owned (specifically Korean) beauty supply stores selling black hair products. Go into the store, ask the employees and owner the most simplest [sic] questions about what they are selling and they don’t know. Selling black hair products, profiting off of our hair needs, yet we are the first ppl [sic] to be followed around in the store, harassed, etc.”

For many Black women, stores like Missha Beauty are emblematic of deep-seated tension within the cosmetic industry. As Kimathi Lewis explains in Patch, “For almost 50 years, the Korean American community has dominated the Black beauty supply market by opening large stores, buying out smaller Black-owned ones and using the faces of Black celebrities on their products and Black employees in their stores to grow their businesses in the Black community.”

Of the 9,800 beauty supply businesses nationwide, only about 300 are Black-owned, according to Atlanta’s Beauty Supply Institute in 2016.

The phenomenon of Asian store owners primarily catering to and profiting off of Black patrons while simultaneously treating them with distrust and occasionally violence extends far beyond the cosmetic industry.

In 1991, Korean American liquor store owner Soon Ja Du shot Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, in the back of the head after suspecting the teenager of stealing orange juice. Du was found guilty of manslaughter, sentenced to five years probation, 400 hours of community service, and fined $500. She never served jail time.

In 2014, Chinese American NYPD officer Peter Liang shot and killed Akai Gurley, a Black man, in the dark hallway of a Brooklyn housing project. Liang was found guilty of manslaughter (later downgraded to criminally negligent homicide), sentenced to five years probation and 800 hours of community service. He never served jail time.

Protests on both sides erupted following the court’s verdict. While one side ― most of whom were Black ― sought justice for Gurley, the other ― most of whom were of Chinese descent ― viewed Liang as a scapegoat for a white supremacist system which desired a sacrifical lamb to appease Black Lives Matter supporters.

Six years later, Black Lives Matter supporters continue to protest ― especially for George Floyd, a Black man who was murdered by four police officers in May. As Derek Chauvin knelt on Floyd’s neck for nearly 10 minutes, J. Alexander Kueng and Thomas Lane applied further pressure to restraining Floyd, while Tou Thao ― a Hmong American ― stood watch to prevent any interference.

Thao was not only complicit in Floyd’s death, but also beat Lamar Ferguson alongside another officer in 2014 by punching, kicking, and kneeing teeth out of the handcuffed victim. Thao’s actions contribute to the history of Black-Asian animosity.

This tension exists in part because of the Black-white binary paradigm which historically shapes our understanding of race. The paradigm accounts for non-Black Latino people and non-Black Asian people by grouping the former with Black people and the latter with white people because of the vacillating level of privilege afforded to each group of color.

While Asian people have historically experienced more privilege than dark-skinned Latino people and Black people, the conflation of Asianness and whiteness, as articulated by the Black-white binary paradigm, only serves to further divide the marginalized groups.

The historical context surrounding Black-Asian relations also rests upon the model minority myth which upholds the Asian community as the “superior” marginalized group. The myth relies on the narrative that Asian Americans are peaceful, stable, and intelligent, and therefore, should be viewed aspirationally by Black and Latino Americans. White Americans and Asian Americans weaponize the myth to simultaneously elevate Asian Americans and denigrate Black Americans.

As Ellen Wu explains in “The Color of Success,” the model minority myth was conceptualized by Asian Americans and reinforced by white Americans circa the mid-20th century.

Asian Americans appealed to white Americans through respectability politics. While many Chinese Americans promoted their traditional Confucian family values, many Japanese Americans touted their wartime service. The model minority myth was soon co-opted by white politicians who sought allyship during the Cold War.

Wu writes, “[embracing Asian Americans as allies] provided a powerful means for the United States to proclaim itself a racial democracy and thereby credentialed to assume the leadership of the free world.”

By the 1960s, white Americans ― especially those in politics ― furthered their investment in the model minority myth to combat the civil rights movement. White politicians on both sides of the aisle propagated the image of the hard-working Asian American to deny the demands of Black Americans and shift the blame for Black poverty. They operated under the premise that if Asian Americans could find success within the system then Black Americans should be able to as well.

The model minority myth thrusts the responsibility of systemic inequity upon the people who most directly feel its effects while simultaneously driving a wedge between Black Americans and Asian Americans.

As the writer Frank Chin said of Asian Americans in 1971: “Whites love us because we’re not Black.”

![]()

Part 5: Bringing it Home

The historical and cultural context surrounding Asian-Black animosity complicates the rise of Asian American artists in hip-hop, but doesn’t infringe upon it. Political at its core, hip-hop exists as a natural sanctuary for innately politicized communities.

Han Han says, “I do what I do for the cultural empowerment of my people through my own personal empowerment reflected in my music and performances. That is basically the ethos of hip-hop: to have a space where the muted voices can express themselves. One thing I love about hip-hop is the sense of freedom embedded in the artform. Perhaps, that is why I resonate with it. Perhaps, it is why people of color resonate with it.”

Through hip-hop, marginalized musicians pave their own path, honing in on their authenticity and liberating themselves from the shackles of society’s expectations. With that being said, in the process of pursuing a hip-hop haven, some non-Black artists forsake their own identities, adopting an imitation of Blackness in an attempt to gain acceptance.

Beyond the layered levels of offensiveness to some musicians’ modern minstrel shows, their mimicry neglects the notion that hip-hop fundamentally demands authenticity. How can artists liberate themselves when they’re pretending to be someone else? And while success, in part, rests upon sales, how can artists attain authenticity when solely seeking external validation?

Belongingness motivates humanity. Above all else, we’re hardwired to crave community, inclusion, and acceptance. Be that as it may, there are some spaces that aren’t naturally conducive to fostering a universal sense of community. But just because that’s the case doesn’t mean that we should then, in turn, reconstruct our identities around our conceptions of the in-crowd. Doing so comes at the cost of alienating not only the people we seek to emulate, but also ourselves. When a fundamental sense of self is abandoned, what remains?

Thus, we recognize the necessity of creating space where one doesn’t exist. Asian American women artists like Han Han, Chloe Tang, and Ruby Ibarra find success in hip-hop by establishing a niche that values empowerment, authenticity, and individuality.

Han Han says, “At the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter to me if I am accepted in the hip-hop industry or not. I don’t need outside validation. I don’t measure the value of my work based on outside validation. Perhaps, that sense of ‘not belonging’ is merely an internal dialogue. I know that I am part of the global hip-hop movement.”