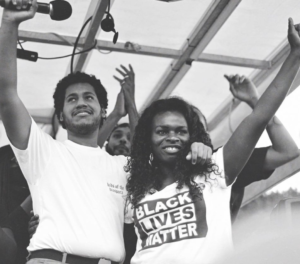

Perched on an elevated platform, Mireille Ngosso, a Congolese Austrian doctor and politician, addressed a lively, mask-wearing crowd of about 50,000 protesters clustered around the Viennese parliament building. “No justice, no peace,” she bellowed into the megaphone through her black mask, which had “Black Lives Matter” imprinted in white letters. The mob of Afro-Austrians, asians, hijabis, and others, squeezed shoulder to shoulder, reciprocated her cries, thrusting their fists into the air.

Days before, scrolling through her Twitter feed, Mireille had come across the video of a Minneapolis cop pressing his knee on the neck of a motionless black man named George Floyd. “I was in deep shock, the video really touched me,” she says. Although Mireille couldn’t have found Minneapolis on a map, she was familiar with the way powerless minorities were dominated by the majority. “I saw my uncle, my brothers in George Floyd.” The 41-year old grabbed her phone and rang up Mugtaba, an Afro-Austrian student activist, her friend from church. “What are we going to do?” she asked. The two agreed to host a rally at the center of Vienna to commemorate the murder. The next day, Mireille submitted the paperwork to the authorities, registering 200 attendees.

Vienna’s Innere Stadt (inner city) is surrounded by the Ringstraße, a circular boulevard, lined with grand Palais (palaces), trumpeting sandstone façades of the Gründerzeit (Founding Epoch) and the Volksgarten (People’s Garden) replete with rose beds, across from which are two identical-looking buildings, the Natural History and the Art Museum, facing each other across an imperial square. Behind it is the Museumsquartier (Museum’s Quarter) and the Platz der Menschenrechte (Human Rights Square), a 90,000 square meter arts’ and culture complex, originally constructed as the imperial stables. Sitting at the center of the plaza is the “Omofuma memorial stone,” a 3-meter grey granite sculpture named after the 25-year old Nigerian refugee whose 1998 application for asylum was rejected. He was dragged onto a plane, bound to his seat with tape, and suffocated during the flight. He is Austria’s George Floyd.

On June 4, 50,000 protestors surrounded the memorial, holding signs reading “Enough is enough” and “Against racism and police brutality” (with “1. May 1999: Omofuma” written in tiny letters). When Mireille arrived, she could hardly believe her eyes. “I’m still overwhelmed,” she says, remembering the immense number of individuals clustered together. “I think this was the first time racism came into their consciousness, and they realized that this could happen here too.”

Despite the imprint Omofuma left on Austrian society, his case is “hardly debated and hardly talked about,” says Mireille. Like him, she is of African descent. The eldest child to two socialists in former Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Mireille’s family fled the Mobuto Sese Seko dictatorship when she was three. After authorities in Italy and Switzerland refused to grant them asylum, Austria awarded them legal status in 1984.

Like other European countries, Austria has admitted immigrants since the end of the Second World War. In 1945, 30,000 ethnic Germans from the Sudetenland settled in Austria. It accepted 180,000 Hungarians after the 1956 Warsaw Pact invasion. Following the Prague Spring in 1968, 160,000 Czechs were granted temporary asylum. The government initiated the “guest worker program” and recruited short-term factory workers from Turkey and Yugoslavia in the 1960s. Thousands sought protection in the country after the fall of the Soviet Union and the breakup of Yugoslavia, and the number of resident foreigners doubled (from 387,000 to 690,000) between 1983 and 1993. Austria has experienced a steady increase of economic migrants since 1995, when it joined the European Union. The number of foreigners in the country surged from 723,483 in 1995 to 1.38 million by 2008, after Czechia, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Slovenia and Slovakia joined the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania in 2007. In 2015, a record of 1.3 million asylum applications entered the EU following political instability in the Middle East and Africa. Austria received applications from 88,000 refugees, triple that of the year before. Today, a quarter of the country’s 9 million people have a so-called “migrant background,” meaning that they or at least one of their parents were born abroad.

When Mireille’s family arrived, they moved into subsidized public housing in Meidling, Vienna’s proletarian 12th district, where pale Gemeindebauten (residential buildings for the working class) border family garden allotments. Around the corner, you can find traditional barn houses, small shops selling old light bulbs and outdated electronics, and the local Beisl (tavern) where neighbors chat over a beer and a hearty Gulasch stew. The family was always short on money, so her father took a low-wage job in a textile factory. A former activist, he continued being politically active in Austria. He attended meetings hosted by the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ). Mireille would tag along. She still recalls party events and the SPÖ’s annual May Day celebration on International Workers’ Day. Meanwhile, her mother stayed home to look after Mireille’s two younger brothers. To help them fit in, her parents drilled an Austrian identity into their kids. “My parents made exaggerated efforts to raise me Austrian,” she says in her perfect Viennese accent. She watched Heimatfilme (literally, homeland-films, usually idealized and nostalgic) set in the Austrian Alps, such as Sissi – the trilogy profiling Austria’s heroine, the Austro-Hungarian Empress Elisabeth of Austria. In the summer, her family road tripped through the country, from scenic mountain towns in Vorarlberg to the lakeside in the Burgenland. Mireille grew up primarily speaking German, while her parents communicated in Kikongo, Kiswahili, and Lingala.

Nevertheless, Mireille still stood out at school. Her dark skin color attracted attention from classmates and teachers, who frequently called her “Neger” the German version of the n-word. To be fair, this was simply the traditional word for “negro.” Until recently, Austrians used the term to describe black individuals, unaware of its connection to slavery. Still, the boundaries of tone can sometimes blur. Kids often asked to touch her Afro curls. At age 16, she had enough. “I dropped out because I just couldn’t cope anymore,” she says. “I certainly didn’t have a household that could support me emotionally. Plus, the name-calling and the racist comments ultimately drove me to the edge.” Austria’s compulsory school attendance is nine years, so it was legal for Mireille to quit. She searched for part-time jobs, began playing the piano, and booked some singing gigs at jazz bars.

![]()

Racism has deep roots in Europe. In the late 19th century, most of the region transformed from a set of multiethnic empires into “homogenous” nation-states. Germany, France, and Italy erected visible or invisible borders, separating the “native” from the “alien” population. The growth of national consciousness helped connect strangers to each other. Individuals enclosed in a common territory merged into groups who believed they shared a common culture, history, and language. Those who did not fit this definition became outsiders.

Europeans devised racial hierarchies, which they imposed during their colonial endeavors. In An Emerging Modern World, Sebastian Conrad, a professor at the Free University of Berlin specializing in post-colonial history, argues that, as a result of the Enlightenment, Europeans perceived themselves to be “cultural people.” Their Christian identity, ideas of high civilization, progress, esteem, and superiority allowed them to distinguish themselves from the “barbaric” and “uncultured” non-Europe outside. The colonizers wanted to assert this “contrast between civilization and barbarism” formulated during the Enlightenment. So they subjected and controlled the Africans “for the benefit of the European culture,” writes Andrew Zimmerman, a professor of German history at George Washington University, in his article “Race and World Politics: Germany in the Age of Imperialism, 1878–1914.”

Such racial hierarchies were not limited to the colonies. Europeans imported practices of ethnic segregation and racial difference to their own continent. They hosted art exhibitions showcasing colonial objects, which they described as “grotesque and bizarre,” and reflections of the Africans’ “undeveloped taste.” During the so-called Völkerschau, Europeans even put Africans on public display. This happened in Vienna too. In July 1896, a record of 22,3000 visitors trekked to the Wiener Prater, the city’s amusement park, to examine the Asante people from modern-day Ghana. It resembled a “human zoo.” People huddled around the Africans, separated from the Austrians with a metal gate, observing their “exotic” features.

On March 12, 1938, cheering crowds greeted the Austrian-born Hitler and his troops on Vienna’s historic Heldenplatz, marking the Anschluss, Germany’s annexation of Austria. Nowadays, Austrians tend to hesitate when talking about their country’s Nazi past. Austria and Germany share a difficult history.

The nation-state Austria only came into being in 1919, after the Allies dissolved the Austria-Hungarian Empire. Under the Treaty of Saint-Germain, Austria-Hungary lost 80% of its territory, and the Austrian “Republic” was created from the German-speaking region. In French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s legendary phrase: “L’Autriche, c’est ce que reste.” – Austria is that which is left. The treaty prohibited any union between Austria and Germany, plunging the former into a political crisis over its identity. German-speaking deputies in the territory assembled and crafted plans to establish a “second German state.” To emphasize the German character, German was adopted as the national language.

When the conservative Engelbert Dollfuss rose to power in the 1930s, he cut all ties to Germany and established a corporate state modeled after Benito Mussolini’s Italy. His ambition was to build an Austrian “Reich” and reclaim “the greatness that Austria once was,” harking back to the Holy Roman Empire, a title held by the Habsburgs from1438 and 1740, and again from 1745 to 1806.

Austrian Nazis assassinated Dollfuss, but his successor, Kurt Schuschnigg, followed his lead and resisted the absorption of Austria into Nazi Germany. However, Schuschnigg failed to keep Austria independent, paving the way for the Anschluss and setting the stage for Nazi violence.

Benjamin Opratko, a political scientist and racism researcher at the University of Vienna, says Europeans often “equate [racism] with Nazi anti-Semitism and the ideology of race. Racism is believed to be a problem, but one that’s ultimately in the past.” After the horrors of the Holocaust were revealed 1945, the Allies vowed to eliminate racial thinking from Germany, in the hope that doing so might have a similar effect on Europe as a whole. The assumption was that racial difference, not attitudes towards it, was the problem. But pretending that differences between people of different ethnicities and religions do not exist doesn’t ameliorate prejudice. According to linguist Ruth Wodak, who researches identity politics, racism, anti-Semitism and other forms of discrimination at Lancaster University, 1945 did not erode the long tradition of European anti-Semitism or prejudice in the region. In fact, Christian anti-Semitic motifs, such as references to Jews as the “murders of Christ” or “traitors,” were frequently employed in newspapers. Elitists instrumentalized cliches about Jewish commercial spirit and the stereotype of the “dishonest,” “dishonorable,” or “tricky Jew” for political reasons. While the open expression of anti-Jewish rhetoric was subject to a general taboo, the ruling elite still professed their anti-Semitic beliefs indirectly.

Additionally, the Allies treated racism as a “German peculiarity.” Racism was perceived to be a product of Hitler’s obsession with racial purity. This gained a stronghold in Germany, due to the state’s ethnocentric nationalism, argues German philosopher Jürgen Habermas. So the Allies believed that rehabilitating Germany would cure Europe’s racism problem. As UC Berkeley professor and historian of comparative modern Europe Rita Chin argues, in denazifiying, reconstructing, and turning West Germany into a stable, liberal democracy, they attempted “to make the question of race a nonissue.” But treating the Holocaust as an individual event perpetrated by one state, and failing to recognize it as a collective European undertaking, was a mistake, says Julie Pascoët, secretary general of the European Network Against Racism. It allowed countries, like Austria and Poland, which also committed crimes against humanity, to distance itself from the Nazi narrative.

With the war beginning to turn, the Allies agreed to the Moscow Declaration of 1943, declaring among other things that the German annexation of Austria was “null and void.” The treaty declared Austria “the first free country to fall a victim to Hitlerite aggression.” This was a convenient fiction that the state took up, allowing it to negate all ties with Nazism and extreme anti-Semites like former Viennese Mayor Karl Lueger, a charming political pragmatist who played both sides; he referred to Jews as “God murderers” while claiming Jews among his friends, going down in history insisting that “I’m the one who decides who’s a Jew.”

So 1945 represented a “historical caesura,” in which Austria “silenced” the Jewish question. Denazification was half-hearted in the reconstituted Second Republic, weakly implemented and poorly enforced. Austrians no longer discussed the Jewish question, and as they struggled to rebuild their shattered country, they effectively buried their Nazi past. This was legitimized with the signing of the state treaty in 1955 ending four-power occupation, in which Austria adopted “permanent neutrality.” The country emerged as a Staatsnation (“nation by will”) following the French model of a social contract among citizens, regardless of race or religion. However, with Austrian identity being rooted in high culture, referencing the hey-days of Habsburg Monarchy, Wodak argues that the state resembles an ethnically and linguistically defined Kulturnation (“cultural nation”) like Germany, wherein the concept formed the basis for Nazi racist theories.

The silence was broken in 1986 when an Austrian newspaper revealed that former Austrian secretary general of the UN and presidential candidate Kurt Waldheim had been involved in the 1942 massacre of Yugoslav in Kozara and the 1943 mass deportation of Greek Jews to Nazi death camps. Waldheim denied the allegations and claimed they were the product of an “international Jewish conspiracy.” Despite the controversy, he was elected president in June 1986.

In 1988, the Austrian government appointed a group of historians to investigate the matter, but it found “no evidence” that Waldheim had committed war crimes. It did, however, accuse him of knowing about the events and failing to stop them and, thereby, “facilitating them.” Despite his personal failure to assume guilt, the Waldheim affair served as a turning point in Austrian history. Since then, the state has publicly acknowledged its responsibility in the Holocaust, with Waldheim apologizing for “the Nazi crimes committed by Austrians” on behalf of the nation on national television on the 50th anniversary of the Anschluss. In 1994, Thomas Klestil became the first Austrian president to visit Israel. Speaking before the Knesset, he apologized for the fact that Austria has “far too seldom [spoken] of the fact that many of the worst henchmen in the Nazi dictatorship were Austrians.” The government designated May 5, the day the Austrian Mauthausen concentration camp was liberated, as the Holocaust Remembrance Day, constructed a Holocaust memorial on Vienna’s Judenplatz (Jewish Square), and hosted two exhibitions – in 1995 and 2001 – about war-crimes of the German Wehrmacht. As of September 2020, Austria has extended citizenship to people persecuted by the Nazis and their descendants.

However, Nazi racial thinking remained. This became clear with the rise of the Austrian far-right Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (Freedom Party of Austria, FPÖ) into government in 2000. Leader Jörg Haider, a Nazi sympathizer and one of Europe’s first right-wing populists, rose to power on an anti-immigration platform, warning citizens of “Überfremdung,” meaning that Austria would be “overrun by foreigners” after the fall of the Iron Curtain. When his party was part of the ruling coalition, Austria reduced labor immigration to key workers, and as of 2003, required all non-EU nationals to attend German language and integration courses. If completed upon arrival, migrants were reimbursed for the tuition, but otherwise, they had to pay for it themselves. Foreigners lost their residence permits if they failed to complete the courses within four years. Haider’s anti-migration policies, xenophobic rhetoric, and opposition to Eastern enlargement raised an eyebrow among other European states, who briefly sanctioned Austria for violating European values.

![]()

One evening, Mireille was approached by some men on the U-Bahn (subway) after leaving her part-time waitressing job serving tables at a restaurant. Since her destination was only a few stops away, she remained standing near the front of the car and fastened her hand on one of the poles. Suddenly, Mireille felt a blow from behind, jolting her forward into a group of people. Puzzled, she swiveled around and eyed two white, middle-aged men leering at her. They called her the n-word, and shoved her. Alarmed, she dashed off to the other end of the subway car. Luckily, she got off on the next stop. Mireille thought she might feel more comfortable in a multicultural city. She redid her Matura (high school diploma) at a special adult evening school at age 23 and moved to London, enrolling at Kingston University for biological sciences. While she enjoyed the buzz and excitement of the city, she missed her family and friends in Austria.

She returned to Vienna three years later to study at the Medical University, where she met Danny Ngosso. Also a Nigerian immigrant, he is a surgeon at a clinic in Bavaria, Germany. They married in 2017 and have a four-year old son, Samuel. While completing her medical residency program, Mireille decided to join the SPÖ like her father. In 2010, she took on a more substantial role in the party, advocating for better healthcare and more affordable housing. Racism was never part of her political agenda. “Ever since I joined politics, I decided that I don’t want to talk about migration or multiculturalism,” she says to me. It wasn’t that she had no interest in race, but it seemed that Austrians, even the socialists, didn’t care. “Whenever I talked about racism, I was simply shut up or not taken seriously. People would say, ‘Oh, look, it’s the black politician who only makes policy about migration and anti-racism.’ But I’m more than that – I’m a mother and a doctor – I have other expertise that I can speak to, so I told myself that I’d focus on other issues.”

Mireille climbed the ranks of the party. She was appointed as district councilor for the inner city in 2015 and deputy district representative three years later, making her the first high-ranking Afro-Austrian official in Vienna. However, not everyone celebrated her rise. Some racists attacked her on a public discussion forum on Facebook, telling her to return “to the jungle” to “pick bananas.” And while Mireille has grown numb to such racial slurs, her loss during an internal party election last March hurt. Despite being a top candidate, she didn’t receive a majority. Mireille believes her colleagues no longer wanted her to represent the district because she is Black. According to the district chief, the reasons for her loss remain unknown, but people in the comments speculate it was due to her migrant background and skin color. Since then, combating racism has become her priority. “No matter where it occurs and regardless if it’s anti-black racism, anti-Muslim racism, or antigypsyism, I always talk about it,” she says. “What we’re dealing with here are injustices, and this needs to be discussed now.”

Even though Austrians today are more likely to discuss race than they were in the eighties, Mireille doesn’t believe these debates are constructive. “Racism comes up again and again within the political discourse, but nothing is really being done,” she says. “If politicians really wanted to change something, they would take action and raise awareness of the issues that presently exist within our society. They would stop publishing racist slogans and instead create inclusive laws, an action plan against racism, install anti-racism commissioners in every institution to protect civilians, and rewrite school textbooks. But, instead, politicians themselves make it presentable, which signals to the population that it’s OK to do the same.” Before they can change the laws, Austrian politicians must change people’s minds. Mireille wants Austrians to recognize that racism exists within society. Only then can Austria become a land of equal opportunity.

But many Austrians simply don’t believe the country has a racial problem. In a recent survey, 94% of respondents claimed that asking someone where they’re from isn’t racist. “It’s very difficult to talk about racism on the political level, especially in a country like Austria where a self-critical discussion about racism doesn’t exist,” says Faika El-Nagashi, Austrian Green Party speaker for integration and a member of parliament. “The moment we talk about injustices, inequalities, power relations and being affected by racism, then we start asking: ‘Who is responsible for it? Who is silent? Who actually does it? When I’m disadvantaged, then who has the advantages?’ These are uncomfortable discussions for many, which is why it’s so difficult to discuss, debate, and reflect.” On talk shows, TV anchors clumsily tried to define “racism,” a linguistic taboo in a society, which favors terms like “discrimination” or “xenophobia” instead.

Austrians seem to be voting with their feet, attending protests against racial discrimination in record breaking numbers. The turnout at the June 4 protest, followed by a rally of 10,000 the next day at the U.S. embassy, proves that the general public wants to have this conversation. “I hadn’t seen this in 20 years,” says Mireille. Following the protest, she realized it was time to speak up. She sat down with members of the Austrian black community. “At the time, we simply said, ‘It’s not enough just to host a demonstration or rally; we also want to have a political say. We want politics to take on these issues and really ring in improvements,’’ Mireille recalls.

![]()

In August, Black Voices was born. Mireille, dressed in a hot pink suit, sat alongside El-Nagashi and other members of the Afro-Austrian community, facing a room full of journalists. She lowered her “Black Lives Matter” mask and picked up the microphone to introduce the Black Voices Volksbegehren, a citizens’ initiative calling for a national action plan against racism. She outlined the group’s demands: anti-racism workshops in companies and schools, post-colonial history taught in schools, expanded voting rights for permanent residents. Black Voices wants the Austrian government to establish an independent control and complaint center against police misconduct, as well as a mental health service run by and for black people and people of color, where victims can report cases of racist police violence. Moreover, the group expects the government to welcome refugees and offer them safe and legal opportunities in Austria, in line with the human rights principles set out by the UN Charter of Human Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights. If the citizens’ initiative obtains 100,000 signatures by September 2021, the Austrian Parliament must put the issue on its agenda.

Volksbegehren (citizen’s initiatives) have played an important role in shaping the country’s political landscape since the 1980s. Instruments of direct democracy, referendums allow citizens to intervene in the parliamentary process. While parties have initiated the majority of Austrian referendums, recent constitutional reforms have made them more accessible. In 1997, a group of women launched the Frauen-Volksbegehren (Women’s Civilians’ Initiative), calling on the state to fight gender inequality. The issue was then discussed in parliament, which implemented some of their demands. The government now compiles annual gender-specific statistics on labor and education, and guarantees two-years paid maternity leave.

Mireille hopes for a similar initiative on racism and minority rights. She doesn’t believe Austrians will confront these challenges on their own. “Mainstream population doesn’t want to give up their seats at the table, they don’t want to open the door for people with a migrant background, but it’s time,” she says. “We are just as much a part of this society, we feel Austrian or Viennese, and we have our place here.”

Initiatives like these have a mixed history in Europe. In 2001, the UN World Conference against Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance held in Durban, South Africa, advised states to adopt a national action plan (NAP) to discuss racism. There has since been a scattered effort among EU member states to create such a program, with Germany launching its legislation in 2008 and Austria never initiating one at all. This past summer , in response to the George Floyd protests, the European Commission proposed a five-year EU anti-racism directive to “achieve a union of equality” across the bloc.

Initiatives and proposals are toothless, but the facts on the ground change when the people change. El-Nagashi is optimistic, as the civilian initiative is borne by individuals who refuse to accept the limits the system imposes upon them. “We have a new generation for whom living in Austria is a given and shapes this country in so many different ways, but at the same time, experiences racism and always has to fight for their legitimate place in society,” says El-Nagashi.

![]()

Asma Aiad, a 33-year old who studies Conceptual Art, is part of that generation. She is also the only non-black member of Black Voices. She believes ethnic minorities must unite to fight racism. “It’s about justice and removing inequalities,” Asma says. “If you’re really against it, then it doesn’t matter what background you have.”

Born in Vienna to Egyptian parents who immigrated for work in the eighties, Asma calls herself a Muslim Urwienerin (a native Viennese). She initiates conversations with the Arabic greeting Salam, then continues in Viennese, peppering her talk with slang words like Oida (“dude”). Asma adorns her head with neon pink, teal, and floral printed silk scarves, which add spice to her otherwise neutral outfits. She matches her red-green Dirndl, the traditional Austrian costume, with an ash-colored headscarf. When swimming, she wears a burkini, a full-body bathing suit (which is banned in France). During the month of Ramadan, she wakes up every morning at 3 a.m. for Suhoor, a light pre-dawn meal to prepare worshipers for the day’s 15-hour fast. But instead of the Egyptian ful medames, a fava bean stew, Asma prefers a traditional Austrian favorite: a slice of rye bread with Austrian Liptauer, a spicy paprika sheep milk cheese spread. She pairs it with Shai bi Laban, Egyptian black tea with milk, her mother’s favorite. Each sip reminds her of her childhood growing up in a tiny apartment in Rudolfsheim-Fünfhaus, Vienna’s immigrant district, with her mother, younger brother Omar and sisters Esra and Hasna. Her father died of a chronic illness two years ago.

Asma’s family has lived in the same apartment since she was born. Its entrance leads you into a tightly-packed living room, where a large, u-shaped, red velvet sofa surrounds a black coffee table. A glass jar filled with dates sits on top of a floral-patterned silk placemat. When performing salah (Islamic prayers), the four children and mother stand, then kneel, in front of the table, their bare feet firmly grounded into the soft red-and-white carpet. They face a TV, from which an imam is leading the prayers. Next to the sofa is a glass dining table, already set for supper. It faces a window lined with white crochet curtains which have a red stripe running straight through them. A colorful mosque decal is plastered onto the window, hidden behind the cloth.

Asma never felt entirely comfortable as a practicing Muslim in Vienna. Her next-door neighbors couldn’t stand hearing the Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer, coming from the family’s TV five times a day. So they routinely called the police. Asma, which means “beautiful” in Arabic, was teased by her classmates, both for her name, and her darker skin color. Once she turned 16 and began wearing a headscarf, she became an even bigger target. In her cooking class at school, the teacher forbade her to wear the hijab, claiming it was “unhygienic.” But Asma quietly put it underneath her hairnet.

The hijab has had a troubled history in Austria. In 2017, the government banned full-face veils in public and in 2018 it prohibited them in kindergartens. A year later, the state outlawed them in elementary and middle schools (a court struck it down in December). Now, the government wants to reinstate the law and expand it to school teachers and girls up to age 14. Officially, Austria is a secular country, and its constitution provides freedom of religious belief and affiliation. Islam has been an officially recognized religion since 1912, along with fifteen others, including Alevism, Armenian Apostolic Church, Buddhism, Catholicism, Evangelicalism, Greek Orthodox Church, and Judaism.

It is a European issue that has vexed many countries. In 2003, Germany was the first to pass anti-hijab legislation, forbidding teachers from wearing a headscarf in state-run schools. In 2004, France outlawed all religious symbols in public elementary and secondary schools. However, unlike the French ruling, which applies to all religions, the Austrian law is limited to the Muslim veil. The legislation does not specifically mention the word “Islam,” but it prohibits “ideologically or religiously influenced clothing which is associated with the covering of the head.” This phrasing allows Jewish kippahs and Sikhs turbans, but bans the hijab, which Austrian politicians claim “prevents girls from becoming confident women.”

So far, neither the European Court of Justice nor the European Court of Human has challenged Austria’s law. According to EU laws, a state must uphold a “principle of neutrality,” which is why the court permits headscarf bans as long as they encompass other religious symbols. This is not the case in Austria, where crucifixes are mandatory in classrooms when the majority of the students are Christian. Meanwhile, Integration Minister Susanne Raab claims “the headscarf does not belong to [Austrian] values.”

Asma doesn’t see anything un-Austrian about the hijab. And she knows what she’s talking about. She has a Master’s degree in Gender Studies and wrote her dissertation on “Islamic feminists,” contemporary Muslim women who free themselves from patriarchal society by wearing a hijab and practicing Islam. For Asma, the anti-hijab rhetoric is simply a form of “sexist discrimination against Muslim women.” On her Instagram account, she writes, “Just as a miniskirt isn’t an invitation for harassment, neither is a headscarf.” Her grit came with age, she admits. “Being treated terribly got me thinking about what I could do to stop it.” At 16, she joined Muslim Youth Austria, a religious group comprised of second- and third-generation migrants that seek to refine the Austrian-Islamic identity. They assert that being both a Muslim and an Austrian is not a contradiction, and that Muslims have the right to participate in every part of Austrian society. Asma participated in the organization’s anti-racism discussions and workshops to connect with people like her. But that wasn’t enough. She itched to undermine people’s assumptions about Muslims, and prove that she and her hijab belong to Austrian society. So she created her blog, dieAsmaah, where fashion meets politics.

One of the first things you notice about her website is a picture of a young Muslim woman flaunting a chic, floral-patterned silk scarf paired with oversized sunglasses. Another picture shows her in a grey bathrobe, her hair wrapped in a matching towel. Titled “This is not a hijab,” the project is a series of portraits showcasing different head coverings that don’t provoke the same criticism as the hijab. “Muslim women are always depicted as suppressed or shown with their backs to the camera,” she says. “I want to counteract this notion, give these individuals their own stage, and highlight their diversity.”

Asma has felt the sting of Anti-Muslim rhetoric. Two years ago, when returning from Istanbul, Asma and her friend were stopped at Austrian passport control. The police officer jokingly asked her hijab-wearing friend, “Say, you weren’t married off there, were you?” Furious, Asma pulled out her iPhone and hit record. On camera, she demanded the man’s ID number. She later tried reporting him to the authorities, but they wouldn’t accept her complaint. She posted the videos on her Instagram account, which made headlines in all the daily newspapers.

Austria’s anti-Muslim rhetoric began when Turkish migrants arrived in the late sixties. Due to labor shortages in the construction, metal, textile, and service industries, the government signed labor recruitment treaties with Turkey in 1964, and with former Yugoslavia in 1966. 265,000 “guest workers,” signed one or two-year contracts, and moved into dormitories near factories, separate from Austrian society.

In 1973, the global economic recession forced the Austrian government to halt the program. Only those with a permanent job could legally remain in the country. The government introduced the Ausländerbeschäftigungsgesetz (Foreigner’s Employment Act) in 1975, which awarded foreigners a two-year, renewable work authorization after eight years of continuous employment. Unemployed Austrians wanted those foreigners who were already there to leave. That year, the government made it difficult for workers to return to Austria if they left the country. Most Yugoslavs returned home, while Turks chose to stay and brought their families to Austria. As a result, the number of Turkish residents tripled between 1971and 2001. The 1992 Aliens Act and 1993 Residence Act tightened regulations, limiting the number of work and residence permits.

Turks and Austrians have a long history of conflict. Beginning in 1529, when Ottomans rioted outside the gates of Vienna, before being beaten back by the Habsburgs. In 1683, the Ottomans besieged the city for two months. But the Habsburgs freed the city for good with help from Polish and German forces. Turkish Martin Luther called the Turkish invasion “God’s punishment of Christianity.”

Austrians remember this history to this day. In the suburbs, it isn’t unusual for a mother to beckon to her children: “It’s already dark; the Turks are coming. The Turks are coming.” One legend about the red-white-red Austrian flag attributes the red to the blood of the defeated Muslims. In Vienna, a statue of a dying, half-naked Turk lying at the foot of his conqueror, John Capistrano, sits in the famed St. Stephan Cathedral. A pillar in the church’s southern tower depicts a Turkish stone head, with the German inscription “Schau, Mahumed, du Hund” (“Look, Mahumed, you dog”).

Austrians grew nervous as Turks integrated into society in the 70s. Turkish cleaning ladies were one thing, but female doctors, lawyers, and teachers –some covering their heads with multicolored silk scarves–were another. The hijab became a symbol, “the border between the violent East outside and an enlightened, modern West,” writes professor Beverly Weber, in her book Violence and Gender in the “New” Europe: Islam in German Culture. The hijab became an equal opportunity point of contention. Conservatives saw it as a symbol of radical Islam. Even those on the left protested that it strips females of their individual agency. Feminists claim that Islam’s suppression of women could “potentially undermine progressivism.” Both sides agreed that Muslim culture does not belong to Europe.

Turks and other immigrants are outsiders. Non-EU citizens must have a work and residence permit to remain in the country. Non-Austrian citizens cannot vote or run for office. They are unable to make an active contribution to their surroundings.

Austrian citizenship is based on the principle of “jus sanguinis” (the right of blood), meaning one becomes a citizen only if one of their parents is Austrian. Unlike in Germany, which awards a form of birthright citizenship, first, second, or third-generation immigrants are excluded from society. One can apply for citizenship, but fulfilling the requirements is expensive. In addition to ten years of continuous residence, the would-be Austrian must have a monthly income of at least 990€ ($1,200) for six months. He must know German, and renounce his other citizenship.

![]()

Camila Schmid, a 22-year old Austrian-born student of international relations, believes that it’s time to speak up. She has beautiful dark curls that fall just beneath her shoulders. Her skin is a soft light brown shade, a mesh of her Cuban mother and Austrian father’s features. In her hometown, a medieval Austrian village situated just outside of Vienna along the Danube river, she says she feels “exotic.” Cami first realized this while hanging out with friends on a middle school ski trip. “Raise your hand if you think your skin color is prettier than Cami’s,” one girl announced. Everyone’s hands shot up, including two of her best friends. She felt betrayed. “I had thought racism comes from ‘bad’ or ‘foreign’ people,” she says. “But racism occurs even when you think you are in a ‘safe space.’” Lost, she turned to guidance counselors and teachers for help.

But they downplayed her racial experiences. “When I tried explaining how I felt, I received ‘gaslighting comments,’” Cami says. “People said, ‘It’s not that bad; you’re exaggerating.’ So I just stopped addressing it.” She felt the need to suppress the discrimination. Europe demands this, argues sociologist Alana Lenin. Since the existence of racism is hushed up in the region, it is not considered part of Europe. So to become accepted and integrated, an individual must act as if racism doesn’t exist.

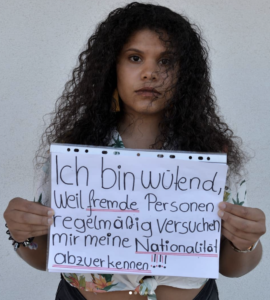

Cami works part-time at a local grocery store. She usually works at the cash register. One day, an older, married Austrian couple approached her to checkout. While the woman popped their food on the conveyor belt, the man gave Cami an annoyed look and complained, “A Cuban! Great!” He was a xenophobe. In response, Cami shook her head and said she was Austrian. The encounter broiled into a heated discussion about her nationality and ended with the police arriving. However, they didn’t file a complaint. A month later, when Cami and her mother were exploring a neighborhood just outside her hometown, a man yelled at them, saying, “Foreigners out! Go back to where you came from!” A cop car pulled up at their house a couple of hours later. The 22-year old opened the front door to find police officers, one infront and the other behind, asking for residence permits. She felt like a criminal. “I am angry, because strangers regularly try to deny my nationality,” Cami writes on her Instagram profile. “I am angry, because my experiences with racism and the pain it brings along are played down and delegitimized by this society.”

Austria never felt like home for Cami. So after graduating from high school, she packed up her belongings and moved to Germany to work as an au pair. That’s where she found her voice. “I met white people who want to talk about racism and are interested in the problems of marginalized groups,” she says. “They gave me the courage to speak up for myself by showing that racial violence is not okay.” Her new friends took her to protests and rallies. German protest culture, which emerged with the 1968 student-led street protests, was new territory. In Germany, she began thinking about discussing racism on social media.

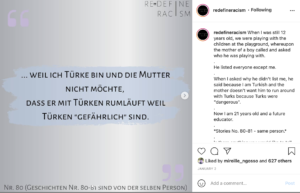

The murder of George Floyd was the final straw. Cami launched Re-Define Racism, an Instagram platform to which non-white individuals from Austria, Germany, and Switzerland share their stories of racism. One post retells an individual’s encounter with a non-white colleague. They said, “Well you were born here, but you’re not really German.” Another post describes a time when they were told to sit at the back of the bus.

Cami hopes sharing stories helps others with their racial trauma. “I want people who experience discrimination to receive encouragement by sharing their stories.” She says she would have felt “less alien” if she knew that others were experiencing the same type of racial hatred when she was growing up.

The 22-year old understands that sharing is hard. “Every time I share an experience, my heart starts pounding, and I feel humiliated.” But she believes that initiating interracial dialogue and educating the white population about racism is key. “I want white people to pay attention, become aware of their privilege, accept that racism is part of other’s reality, and reflect on what role they play in it.” In a recent Re-Define Racism post, a white individual regrets playing the racist school yard game “Who’s afraid of the black man?” Common in elementary and middle schools, one child, the “black man,” faces a group of others who are lined up in a row. The kids must run to the opposite side without being caught. Those that get caught have to help the black man. The last one standing wins. The “black man” is not defined as a specific ethnic group, but, when reflecting on it, the individual is appalled and wonders how people of color must feel when playing this game. This is exactly what Cami aims to achieve with her project.

![]()

“See this photo behind me?” Simon Inou asks me, pointing at his Zoom background. He has a big grin on his face. He is wearing a green and orange floral-printed button-down shirt that compliments his chocolate-colored skin tone, a red-green-yellow knit hat that covers his bald head, and thick brown, square-shaped glasses. Behind him is an image of the June protest depicting white and non-white individuals joining arms and hoisting posters into the air. “Awareness has reached Austria. Young individuals are actively fighting structural norms because they don’t want to be manipulated anymore,” he tells me. The Viennese George Floyd protest was a turning point for the African journalist and media critic. It was the culmination of the battle he has been fighting for the past 20 years.

Simon sought asylum in Vienna in 1995. Born and raised in Cameroon, the 50-year old says he comes from a “large royal family” that dates back to the 11th century. He remembers attending luxurious family banquets in his childhood at which entire cows were roasted and served for supper. Simon developed ambition and curiosity at an early age. At 19, he founded the country’s first youth newspaper Le Messager des Jeunes. He also enrolled at the University of Douala to study sociology, and he covered politics for the weekly newspaper Le Messager. He criticized the government in his writing, which eventually got him into trouble. Simon was almost arrested in Cameroon. He fled the country and set out for the German-speaking region. Growing up in a former German colony, he had always been drawn to Austria and Germany. His grandfather spoke native German, and Simon, native in English and French, had been jealous.

Upon settling in Vienna, he was determined to assimilate. Simon learned the language and enrolled in the University of Vienna to study journalism. While reading local newspapers, he realized that local reporting discriminated against Africans and people of color. He says that he did not feel accurately represented in the media. At the time, Austrians were not likely to talk about, or recognize, racism. And Simon felt it. On the train, people moved away from him. Strangers, newspapers, and national television used the German n-word. When exiting stores, he was stopped by the owners and asked to empty his pockets. At protests, he watched policemen shove other Africans to the ground. Now, Simon is an Austrian citizen and married to an Austrian woman, with whom he has three children. Reflecting on his past 20 years in the Austrian capital, Simon says, “A black person needs a lot of courage to live in Austria. One needs a lot of patience and thick skin to not immediately feel disempowered.”

Since Austrians made no space for Simon he created his own. He wanted to represent himself. “I try to make Africans the main subjects of the reporting,” he says. In 1998, he and some friends founded Radio Afrika International, and in 2003, he became the editor-in-chief of Informationsportal Afrikanet, the German-speaking region’s first digital magazine for the African diaspora. He created a monthly “Africa” supplement which ran in the oldest Austrian newspaper Wiener Zeitung between 1999 and 2004 and wrote a weekly page on immigrants in Vienna, funded by the EU and the City of Vienna, for the daily newspaper Die Presse. More recently, he became the publisher of fresh, the first Afro-Austrian lifestyle magazine. He hosts annual networking events, such as the Black Austria Youth Forum and the Black Austria Awards, bringing together members of the community from the whole country. He leads conversations about how black Europeans can deal with racism. “We must learn to speak a common language to voice our problems even louder together,” says Simon.

He organized the first anti-black racism protest in the country in 1998. “We, people of African origin, took to the streets with some white individuals,” he recalls. The protest, which attracted just under 100 individuals, was just the start of a slew of similar initiatives. In 2007, Simon co-founded “Black Austria,” a media campaign targeting anti-Black racism within Austrian media. The group spoke out against the Moor’s head logo used by the Viennese coffee brand Julius Meinl. Simon also protested against an advertisement for an ice cream version of Mohr im Hemd, an Austrian chocolate dessert that resembles an English Christmas pudding. Captioned “I will mohr” (“I want mohr.”), the ad repurposed a racial slur.

Despite his efforts, fighting for black rights in Austria seemed like a lost cause. The country lacked racial awareness. Only some companies ended their racist campaigns. So 15 years into his fight, Simon retreated. He was tired of fighting a hopeless battle. “I’m confronted with so many challenges that are still new in Austria but have been issues in other European countries for at least 30-40 years,” he says. Simon blames politics and state institutions. “They act as if anti-racism is just the vision of a certain group of people,” he says. “Anti-racism is not an accepted reality in Austria.”

Mike Brennan, a black US citizen and former physical education teacher at the Vienna International School, is living proof. On March 11, 2009, he hopped onto the Viennese subway en route to meet his girlfriend. Shortly before getting off, a blow hit him from behind, forcing him to the ground. One man jumped on him, throwing punches and smashing two of his lumbar vertebrae. A second man joined in. The attackers only identified themselves as police officers once Brennan’s friend threw herself at one of them. Brennan, looking back at the event that left him sitting in a wheelchair for four years, writes, “George Floyd, that could have been me. That is exactly what happened to me in Vienna. I was just lucky that someone intervened. Otherwise I might be dead.” Brennan never received compensation for his pain and suffering. The authorities declined his legal appeal, stating that the police officers’ actions were “not intentional.” Only one of the perpetrators was sentenced to a fine, which the judges reduced. The officer wasn’t suspended but was relocated to another city instead.

To Simon, the Brennan case was a breaking point. It confirmed that the Austrian public refuses to acknowledge their racism. Simon wrote an article for the Austrian daily newspaper Der Standard titled, “Who Will Be Next Black Man?” He had no reason to believe that anything would change for the better. So he stopped giving interviews and withdrew from the public eye.

But with 50,000 individuals screaming “no justice, no peace” in central Vienna, things have started to look different. Simon has regained hope. “People can be as pessimistic as they want. But this awareness is now all across Austria.” Social media and years of day-to-day hate speech drove individuals of all skin colors and religious affiliations to the streets. Now, “it’s no longer just black people fighting against racism,” Simon tells me. White individuals have their backs.

Statistics show this too. The number of recorded hate crimes against ethnic minorities have skyrocketed in 2020, and the majority were made by observers, according to the anti-racist organization ZARA’s latest report. Austrians are beginning to crack down on their own racism. They are determined to eliminate it.

This same spirit drove some 3,000 individuals to the streets on March 21, the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The protestors marched in Vienna’s inner city, united against anti-black, anti-Muslim, anti-Asian racism, antigypsyism, anti-Semitism and all forms of discrimination that divide Austrian society. At the end of their walk, they gathered in front of a stage, where Mireille spoke up against racial injustice.

The recent protests have given Simon new strength. Together, colored and non-colored individuals can slowly bring racial consciousness to Austria. “A black Austrian is just like a white Austrian. We have to build this country together. But, can we break the structural barriers that exist? That’s where I say, ‘There may be some new hope.’”