When Dissidents Grow Old

Tiananmen exiles’ unachieved political ambition and historical trauma in the past 31 years

by Fan Chen

The Goddess of Democracy in Tiananmen Square, 1989 . Photo by Peter Charlesworth/LightRocket via Getty Images

Lv Jinghua, Wang Youcai, Wang Juntao and Zhou Fengsuo were in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4, 1989, when the Chinese military cracked down on the thousands who had gathered. They had protested, slept, and led hunger strikes at the site since April, when furry willow catkins drifted in the city and signalled its awakening after a long, bleak winter. By June, the sun started to scald and the square sweltered. The four protesters were at peak of one of the biggest national protests for democracy and freedom of speech in China.

The night before, tumult and unrest were brewing. Lv heard gunshots at 11:30 p.m. She saw the first tank lumber in from the west of the square and crash a short wall of mud into dense smoke and dust. The tank halted between the gate where a portrait of President Mao was hung and the blue tents of the Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Federation at the northwest corner. Lv had been a broadcaster for the past few months. Among other members of the union who froze seeing the tank, Lv grabbed the mike and yelled until her throat drained, “Everybody out! Tanks arrived!”

Wang Youcai was a short four-minute walk from the square, leading a discussion with other leaders of the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Federation at the Beijing Hotel. The loud, clear gunshot stung his nerve. “The first thought that ran through my mind was: I needed to go back to the tents,” he recalled. He dropped the chopsticks and ran to the square.

At the outskirts of the square near the entrance which the army had blocked, Wang Juntao was walking back and forth under the dim, yellow light at a crossroad. He saw soldiers of the People Liberation Army whose motto was “Serve the People” shooting at citizens under an olive canvas cover in an anchored truck. He saw citizens crawling on the ground and throwing bricks to the army. He saw, for the first time in his 31 years, a corpse several feet away, its eyes open and head split, dripping blood. He gawked at the body and realized, “A heavy day had entered Chinese history.”

Zhou Fengsuo was at the Monument to the People’s Heroes, the center of the square, the eye of the storm. He sat there until the last moment beside the Goddess of Democracy, a ten-meter tall statue. It leaned forward, her dress flying, arms aloft, holding a torch. Yet the last scene that Zhou saw of the goddess, before a gun pointed at his back and forced him to leave, was her being pulled down, torn apart and collapsed in fire. Tiananmen Square, in Chinese meaning “the gate of heavenly peace,” was finally cleared.

At the time, the four protesters did not know that was the end of the 1989 Tiananmen Movement, one of the biggest—and probably the last—civil disobedience in the contemporary history of China. Nor did they know each other well until they reunited years later in the United States as political refugees. Since then, Lv Jinghua, Wang Youcai, Wang Juntao and Zhou Fengsuo have been exiles of their homeland for decades. Over the past 31 years, they have become revered protesters and countless times have told the story to their families and in public of how they became “historical sinners” in jail, how they fled on a ferry in the dead of night, how they protected other victims from political persecution and helped them escape.

To the former dissidents who now live overseas, the 1989 movement has not ended yet. They have carried the 1989 memory like a cross and consider its preservation a life mission. They have established funds and non-governmental organizations, lectured in schools and in cultural salons, organized overseas democracy movements, and even founded various democracy parties to rally participants. These are the extension of their unachieved political ambition to topple the Communist state, a way to heal the embedded historical trauma of the military crackdown, and a form of self-redemption from the survivor guilt that has haunted them since they sought refuge abroad.

But they also see that to some extent, the spirit of the movement did die in 1989 and how impossible it is to bring back the kinds of demonstrations that once gripped the hearts of thousands of young dissidents. The passage of 30 years has diluted the seething anger and agony, and the force of overseas activism has ebbed. Support for their movement from Americans waned as the Tiananmen Square Protest faded out of the headlines and as the US-China relations warmed up under the Clinton administration. The Tiananmen emigres realize that the influence the movement can wield now is limited, and possibly no more than pallid consolation for those who endured the pain. Their lives have thus diverged. Some have moved on and started a new life as an American citizen. Some have buried the history deep inside and continue to struggle with their memories. Others have insisted on movement action and turned it into a livelihood.

If there is one common feeling the Tiananmen exiles share as they enter their 50s, it is a mix of embarrassment, unwillingness, and the bitterness of growing old with an unfulfilled political aspiration. The 1989 movement changed and defined the second half of their lives in a strange land so much so that they became obsessed with their “anti-China” dissident identities. While tides of the world rise and fall, the exiles found themselves stuck between their old and new identities, fighting against not only the Chinese Communist Party, but also historical amnesia and sense of marginalization.

![]() Lv Jinghua barely remembers what she felt because she barely felt anything on her first day in the United States. She was too exhausted to digest what she had experienced since June 4. It was a two-month long hide-and-seek from the government with the bet on her life and safety. Fear and anxiety about the enormity of the uncertainty she faced twisted together and crushed her sanity. All that mattered was to survive.

Lv Jinghua barely remembers what she felt because she barely felt anything on her first day in the United States. She was too exhausted to digest what she had experienced since June 4. It was a two-month long hide-and-seek from the government with the bet on her life and safety. Fear and anxiety about the enormity of the uncertainty she faced twisted together and crushed her sanity. All that mattered was to survive.

Lv’s name showed up on the government’s most-wanted list a week after the military clampdown, and overnight, from an ordinary owner of three dress shops and a broadcaster for the workers’ union, she, at 29, became a “rioter” and political criminal. She decided to flee when she found out the police had stopped and frisked her neighbors to get information about her. Lv dialed all numbers on a stack of name cards she collected during the protest, and finally reached out to a reporter in Hong Kong who told her to meet at the train station.

The next morning, Lv arrived at the platform with a bag of a few shirts to change, some cash, and a phone book of all worker protesters’ contact information. She bought a newspaper, rolled it, and called the reporter at the booth with a one-time phone card. Soon she saw two women, about 30, walking one after each other towards her. The two recognized Lv immediately: a young, plump woman with short curly hair, about five foot three inches tall in a red top and carrying a backpack. Most important, they saw Lv—among a crowd of people reading the flat open newspaper—holding a roll of it instead, just like them. That was the signal they had agreed to on the phone.

Both Lv and the two women stopped for a second the moment they saw each other. Lv recalled, “I was thinking: what if they are spies or plainclotheswomen from the government?”

Later she knew that the two women had the same concern as she did. They were members of Operation Yellowbird, a Hong Kong-based action to rescue Tiananmen dissidents from government arrest and help them flee overseas through Hong Kong. The rescue began right after the protest crackdown, when activists in Hong Kong created a list of dissidents they believed could form the nucleus of “a Chinese democracy movement in exile.”

Rescuers of the Operation had made at least a hundred attempts to go to Mainland China and reach out to the dissidents. To send signals, they carried jamming devices, night vision goggles, and infrared receivers. They also had cosmeticians and multiple fake documents ready to better disguise the protesters. The action took place in major cities of all parts of China. Usually the Operation dispatched two groups of members: one to meet and vet the dissident; the other to arrange a detailed escape plan. The hardest part of the plan was to first smuggle the political criminals to Hong Kong, a transfer station from which they could leave for western countries. Transportation varied from car, train, flight to smuggling speedboat. Local mobsters, smugglers, and Asian mafia, the Triads, were also involved in the rescue. They drew five rescue routes in total and bribed border troops at each stop with their connections all over Mainland China.

Lv followed the women and took the train to Guangzhou, a humid southern city 1,325 miles from Beijing. There, she hid herself in the loft of a student dormitory for the entire month of July, waiting for updates. On August 21st, the operation gathered Lv and five other dissidents in a dim-sum restaurant, ready to flee Hong Kong. But they ended up staying in a still boat for the whole night. The first attempt failed. “It was either because the organizers felt unsafe escaping that night, or that they hadn’t settled the price with the boatman,” Lv recalled.

The next day, August 22nd, the protesters were transferred to Dongguan, a coastal city closer to Hong Kong than Guangzhou. Lv arrived at the Hu Men ferry terminal at 8 p.m., and climbed into a smuggle boat that barely fit them all. It was too dark to see anything including the color of the boat, she recalled. All she heard were the waves lapping the rocks and the throbbing of her heart. About 10 minutes after departure, a soldier from a patrol boat of China Coast Guard, which had circled them twice, transferred all six of them to the patrol boat. The soldier even came to the bottom tank, showed his respect and sympathy with the protesters, and asked for their signatures. By 9:55 p.m., they arrived in Hong Kong. At the front of the line was a minivan with a flashing light. Lv got in to be taken at last to the operation office in underground Mong Kok.

There, Lv met the chief organizer of Operation Yellowbird, Chen Tat-Ching, who others nicknamed “Brother Six.” Chen gently patted her on the back and said, “Don’t be afraid. You are home. You’re safe.”

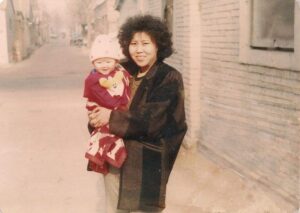

Lv Jinghua and her daughter in Beijing, 1989. Source: Amnesty International (www.amnesty.org)

From 1989 to 1997, Operation Yellowbird assisted more than 400 dissidents to seek safety abroad, including 7 of 21 of the government’s most wanted Tiananmen ringleaders. So as not to alert the British colonial authorities, the Operation raised rescue money privately. The fear was repercussions from Beijing after Hong Kong’s transfer to China, which would take effect eight years later, in 1997. Donations came mainly from civilians, local businessmen and celebrities. Dissident relocation cost anywhere from $6,500 to $65,000 to cover transportation, visa, and resettlement expenses. In Lv’s case, it took about $15,000 to get her abroad.

But among hundreds of successful rescue attempts were deaths and injuries. Two of Chen Tat-Ching’s organizers died in a boat collision and shootout with the police in Hu Men ferry terminal. Another two were burned in a fire when they dodged a patrol speedboat with lights off at night and crashed into a rock in thick fog. In October 1989, the Operation members received false information when rescuing Wang Juntao, leader of protesting intellectuals. Secret police trapped Wang and members of the Operation, and exposed their escape plan to Beijing. More than a hundred people were interrogated and Chen had to terminate his future involvement with the fugitives in exchange for getting Beijing to release his operatives.

Activists of Operation Yellowbird also managed to lobby government and intelligence agencies of western countries like France and Britain to provide political refuge for the Tiananmen fugitives. In October 1992, President George H. W. Bush enacted the Chinese Student Protection Act, which established permanent residence for Chinese nationals who came to the United States between June 5, 1989 and April 11, 1990. Targeted at students, the Act over the years has granted green cards to about 54,000 Chinese nationals. Lv Jinghua, Wang Juntao and Zhou Fengsuo all benefited from the Act and its related bills. In 1994, Wang flew to the United States under compassionate release. In 1995, Zhou arrived in Chicago on a family visit visa to join his wife. He obtained citizenship a few years later.

Lv’s first few years in Los Angeles required her to start from scratch. She barely knew any English, and had to remember the shape of each word on the bus station to not get lost. In spite of the $400 monthly pension for political refugees, which covered her rent and daily expenses, she nannied for a Jewish family in the morning, waitressed at a Cantonese restaurant in the afternoon, and took English classes at night. She saved her money and spent little. Her biggest expenditures were fees for international phone calls and a flea market red dress she bought for the daughter she had left behind, hoping for reunification soon.

“My daughter will be the only reason if I ever regret joining the protest,” Lv said. Her daughter, Yuebei, in English meaning “the northern moon,” was only a year old when Lv fled Hong Kong. The day Lv went to the train station, she left home in the early morning while Yuebei was asleep. Somehow the baby woke up, stared at her, and pinched her clothes, prattling. Lv quieted Yuebei, removed her little fist from her own hand, and left. She often thought about that scene, when, a year later, browsing all colorful girl’s dresses at the flea market, that five years would pass before she saw her daughter again. “I wanted my daughter to come here and live with me,” Lv said, tears welling up her eyes. “That thought held me through all my hardships here.”

On December 16, 1994, the six-year-old Yuebei showed up in the airport in that red dress with puffy sleeves. But seeing her daughter, Lv was not as thrilled as she expected to be. Instead, she felt strange. “I hugged her, but actually I was thinking: is this girl my daughter?” Lv recalled. “I could hardly recognize her. How has that little baby grown so much in the past five years? Where have I been?”

![]()

Everyone who enters Zhou Fengsuo’s apartment on Davenport Avenue in Newark notices the white stucco figurine on the wooden dining table. It is the Goddess of Democracy, the only decorative element in Zhou’s humbly furnished space. On the floor is a white mattress covered in grey-striped sheets, aside from a half-opened suitcase full of clothes. By the wall are stacks of books about the evildoings of the Chinese Communist Party. Beside the statuette is a blue crystal medal Zhou received for his contribution in human rights, along with a white mug imprinted with the smiling faces of two children. They are Zhou’s son and daughter.

Everyone who notices the figurine asks Zhou questions about the protest. What exactly happened after June 4, Uncle Zhou? How did you endure all the pain and start a new life here, Mr. Zhou? Young human rights lawyers and curious students ask. Zhou, now 52, emerges from the kitchen in a navy linen blazer and jeans. He is about six feet tall with a sharp, square face. He takes off his yellow apron and greets his guests that usually include families of political refugees, school teachers, journalists, and cultural events planners. He reclines on a swing armchair, and answers questions. The story often starts with the day when his sister turned him to the police, sending him to prison, where he spent a year with Liu Xiaobo, the renowned critic and later a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. And it usually ends with the current situation of other Tiananmen exiles who moved to the United States, some recently, with the help of Humanitarian China, a non-governmental organization founded by Zhou. “This is what I do for a living now,” Zhou explained the next day. “I bring people together, share my stories, and see if those words could make a difference—either a donation or connections to more people.”

From a physics student at Tsinghua University whose life goal was to become a successful tycoon like George Soros, Zhou is now a full-time activist for the Tiananmen exiles and political criminals wrongly accused in China. The Tiananmen Square protest was the starting point for everything in Zhou’s life since then. Despite his dedicated resistance to historical amnesia and the Chinese Communist Party, he has reconciled with his traumatic Tiananmen memory. He lives with it. He depends on it. He protects it.

Zhou Fengsuo in Harvard University on June 4, 2019. Source: Jingye Liu, Epochtimes

During his first few years in Chicago, Zhou was enrolled in the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and worked part-time as a waiter and pizza delivery man. Local media and human rights organizations also frequently invited him as a former student protester to share his June 4 memories. Lv Jinghua was often the other guest speaker representing the worker protesters in the movement. She remembered that at the beginning, Zhou had a serious trouble telling his story and stammered a lot,“Especially when we talked about the military crackdown,” she said, “he sat still, murmuring to himself, and suddenly buried his head to his legs. Fengsuo was so ruined by the protest and the prison.”

Zhou eagerly sought a sense of belonging within the Tiananmen exile community in the United States, but was disheartened by response to what they had endured. The media put far more weight on reporting the impact of Chinese economic reform as China privatized and its relations with the United States warmed during the Clinton administration. Although President Bill Clinton had criticized President Bush for not pushing China harder in the Tiananmen incident, he made profitable trade a priority over the promotion of human rights and voted to support China’s membership in the World Trade Organization. The news disillusioned many Tiananmen exiles who had counted on the United States, the country of their political ideals, to defend and promote justice for them.

In 2000, in federal court in New York, Zhou and four other Tiananmen veterans sued Li Peng, leader of China’s parliament, accusing him of human rights abuses. The case was the first of its kind in this country against a Chinese official. Li was attending a United Nations conference in that week and was served with a court summons. Zhou knew no one would show up at the hearing, yet he still dressed up in a suit that cost his first-month salary as a marketing intern. “It was a symbolic move,” Zhou said, “but also a relief for me and other Tiananmen victims, that at least someone was still doing something.”

Zhou co-founded Humanitarian China in 2004 with his college classmates, also Tiananmen protesters. The tax-exempt charity collects microloans and assists about 100 Chinese political prisoners of conscience and activists annually to readjust to life after prison. It fosters a new community and becomes a political force for democratization outside of China. In one special case, the organization helped Fang Zheng and his family relocate and resettle in the United States. Tanks had crushed Fang’s legs during the protest.

Over the years Zhou realized that without policy support, the influence of a non-governmental organization is limited. Funding is his major concern. “For grants, the government does have their preference over different human rights issues,” Zhou explained. “The Tiananmen victims are too old and too far away from the center of the discussion. The Uighur Muslims, the Tibetan activists, the Hong Kong protesters could easily get funded now, but not us.”

Humanitarian China receives about $230,000 donations a year, much of it coming from the pockets of its co-founders. Other contributions come from Internet appeals and from people who Zhou has invited to his apartment to hear his personal history. Soliciting grants and donations has forced him to confront his most traumatic memory again and again in conversations, lectures, panel discussion, often with the risk of being challenged and misunderstood by those in the audience who favor the Chinese Communist Party. “I still dream of the night being chased, caught and locked up in prison by the police” he said.

Zhou’s mission of preserving the Tiananmen memory and defending prisoners of conscience came at a price. In the past 31 years, many of his friends from whom he asked for donations had shied away from him, not willing to be haunted by history anymore. His wife divorced him because he spent too much time on the NGO and earned too little to support the family. In 2017, Zhou quit his well-paid investment banking job on Wall Street to run the organization full-time. His son and daughter, both in middle schools, barely showed interest or understood his history. Wang Juntao, Zhou’s friend and his prison inmate after the military crackdown, has a more nihilistic view about Zhou Fengsuo’s martyrdom:

“The 1989 Tiananmen Square protest made a group of people, like Fengsuo, live a life that should not be theirs,” he said. “Students devoted everything to the protest: their life, passion, naïve dream of democratization, and their naïve ambition that they are the ones who make that happen. But students did not think of or prepare for the defeat. They were too proud, too well-off, and too privileged to ever taste any failure in their life. When they failed, most protesters could not accept it mentally. Besides anger, confusion, and embarrassment of facing the reality was humiliation of the defeated.”

“It is not that they are not great, but that greatness is fundamentally a distortion of normal life. History honored these students with trauma and pain that they had to endure all the time and carry for their entire life like a cross, otherwise it became their betrayal. The protest had stolen their life and kidnapped their identity.”

From left to right: Wang Juntao, Fang Zheng, Zhou Fengsuo. Source: Visiontimes.com

But to Zhou, working as an activist and repeating his personal accounts has scabbed the wounds of his soul, and raised the morale of those who join him in his lifelong fight against the Chinese Communist Party marginalization of the Tiananmen memory. He holds an annual candlelight vigil in San Francisco Chinatown on June 3rd every year. On Twitter, with more than 10,000 followers, he seizes every political scandal in China as a chance to promote democratic values. Occasionally, he has fallen into conspiracy theories, like calling the recent outbreak of COVID-19 the “intended biochemical weapon released by the Chinese Communist Party.” He opened a YouTube channel to document an oral history of Tiananmen, and gained 31,500 subscribers. He raises funds to build the Liberty Sculpture Park by Interstate 15 in California’s Mojave Desert. A Tiananmen dissident and sculptor, Chen Weiming, purchased the land in the town of Yermo in 2017. They restored the tank and the Goddess of Democracy 64 meters tall in the middle of the desert. In Zhou’s words, as protesters are getting old and the June 4 memories fade away, they need a physical representation of the spirit, “something eternal and not eroded by time.”

Recently he was rereading Lord of the Rings by J. R. R. Tolkien, the book which he first read in high school and did not quite understand then. He often thought of the character Frodo, and felt ever more identified with him. “[Frodo] was a nobody, but bestowed a larger-than-life mission by accident,” Zhou said. “The 1989 protest bestowed the mission on me to not walk away, but live with its trauma and memory, like a lightning rod.”

Liberty Sculpture Park in Yermo, California. Source: Twitter @AotearoaAi

![]()

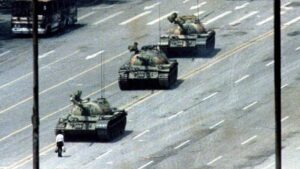

In a chilly wind on Broadway, on the night of Feb. 8, about 30 young Chinese emigres stood in a line behind Times Square’s Red Steps, all dressed in navy caps embroidered with the word “Democracy” in Chinese characters and wearing white t-shirts over their puffy down jackets imprinted with the “tank man,” the most enduring symbol of the Tiananmen Square protest of June 4, 1989.

Tiananmen Tank Man, Beijing, 1989. Photo by Charlie Cole. Source: BBC News

The men and women slowly unfurled blue banners that read in English, “Down Down Xi Jinping!” “Free Free China! Democracy China! Human Right China!” They were members of the China Democracy Party, most of whom are undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States in the past few years. Few, if any of them are old enough to have experienced the 1989 protest directly, save their leader, Wang Juntao, the experienced, ardent political dissident active since the 1979 Democracy Wall movement and jailed twice. In a grey jacket and the same navy cap that all others were wearing, Wang strutted up and down the line, his belly protruding: “If I’m caught by the police in China,” he joked, “people will think that I’m a corrupt government official under shuanggui instead of a democracy movement activist. I’m too fat to look like I’ve suffered.”

Wang Juntao named the protest he staged at 47th and Broadway “the Jasmine Operation,” paying tribute to the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia in 2010. Later it became a weekly routine of the China Democracy Party co-headed by Wang Juntao and Wang Youcai. In 1998, after his jail terms ended, Wang Youcai and several other Tiananmen dissidents founded the Party in Hangzhou, a city 800 miles southeast of Beijing. The government refused to authorize the group and sentenced him to 11 years in prison for subversion. He was released from prison under international pressure from the U.S. and has exiled in New York since 2004. In 2006, the party reconstituted itself, holding its first congress at the Sheraton Hotel in Flushing, Queens. Unlike Zhou Fengsuo’s NGO with its transparent accounting and few complaints, the Party is often tangled in a web of financial disputes including profiteering from party members.

The party establishment and reunion added a new force to the overseas Chinese democracy movement which was mainly composed of two major organizations: Federation for a Democratic China, and the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars. Both were products of the June 4 military crackdown and were populated by the large influx of Tiananmen exiles in Europe and the U.S. Over the years, the Federation for a Democratic China has established its branches in more than 10 countries, including Japan, Thailand, New Zealand and Singapore, participants amounting to 3,000 people. The student federation developed its members from about 40,000 international Chinese students in universities in the U.S. In the 1990s, the federation pushed the Congress to pass the 1992 Chinese Student Protection Act, and united with student unions in Canada, Germany, Taiwan, and Hong Kong, forming a global community of pro-democracy Chinese students.

China Democracy Party shortly revived the oversea democracy movement by opening a venue for the progressive to counter the Chinese government more directly. But it did not stop the movement from declining in the 2000s. Externally, western countries more or less loosened their sanctions against China on human rights issues for national security and business interest. Internally, infighting increased within different organizations, and the disheartened exiles gradually retreated under the pressure to make a living. Almost all the infighting did not involve serious divergences in political ideologies. The cause of fights were often power struggles, financial issues, audit scandals, personnel arrangement, and moral, behavioral problems. Almost all of the activists accused of corruption have not been legally confirmed as criminals or punished by laws or certain groups. The scandals and infighting drew attention at first, but always ended up doing nothing. Meanwhile, wary of Chinese Communist Party’s penetration, the federations mobilized several rounds of “Catching the Spy” activities, a notorious tradition of the Cultural Revolution.

In a review of the history of Chinese oversea democracy movement, scholar Zhou Yicheng explained that many Chinese exiles and democracy activists did not understand, nor were unwilling to abide by, the norms of democratic politics. He wrote, “To some extent, the culture of infighting and whistleblowing is the political culture of the Chinese Communist Party.”

Zhou Yicheng compared the Chinese overseas democracy movement to the Tibetan Independence Movement. He pointed out that in the past 50 years, about 1.4 million Tibetan exiles really formed a democracy composed of about 50,000 constituents, a supreme court, congress, and an exile government. Meanwhile, the Tibetan community exported their Buddhist spiritual values. Zhou wrote, “In contrast, the Chinese exiles movement never actually formed its constituency. In addition to accepting and learning the modern democratic political system, applying for all sorts of international aid, Chinese exiles failed to provide the West oriental, spiritually meaningful products. What they provided was at most accusations and disclosure of the sinful Chinese society, and the role of hero they weakly played on the international stage.”

[pullquote]”What they provided was at most accusations and disclosure of the sinful Chinese society, and the role of hero they weakly played on the international stage.”

The direct result of the cacophony within the democracy movement in the past 31 years is that more and more disheartened Chinese exiles dread politics and steer clear of it, cutting the movement’s financial resources. One of these people is Wang Youcai. Even though he still heads the Party, he has gotten rid of most of its business. He was disappointed that the Party was no longer a locus for their ideal, genuine activism for a better, democratic society. “Rather, it became more of a profit-driven politics company that provides immigration service for Chinese nationals,” Wang Youcai said.

[pullquote] “Rather, it became more of a profit-driven politics company that provides immigration service for Chinese nationals.”

He examined the Party’s account during the first few years of his term. According to Wang, aside from the one-time membership fee of $1,500 and a monthly maintenance fee of $20, some party members pay Wang Juntao a court fee of from $500 to $2,000, sometimes even more. “Immigrants paid the court fee when they managed to get the green card for a political refugee,” Wang Youcai explained. Immigrants usually join the weekly protest in Times Square, where Wang Juntao and a cameraman take photos and videos to advance their case for political asylum. In two to three years, the total amount of money Wang Juntao receives might add up to a million dollars, Wang Youcai said. “Often party members stop attending protests and disappear once they get what they want,” he said. “Few stay to do what they are really supposed to do.”

Other than its financial dispute, the organizational structure of the Party became messier over the years. A Google search shows that there are about eight political parties with titles similar to the “China Democracy Party.” To name a few: China Democracy Party USA Headquarters, China Democracy Party National Union, China Democracy Party Oversea Committee, and China Democracy Party Union Headquarters. Yet none of these “headquarters” and “committees” affiliate or coordinate with each other. Over the years, some organizations have ceased their activities and exist in name only.

Wang Juntao did not deny Wang Youcai’s accusation. But he does not think it is totally unacceptable to “provide immigrant service for the people in need. He said, “Don’t be too obsessed with concepts. There is none. Even if I provided immigrant service to those people, I live up to my own conscience. Why? True that they did not join the democracy party genuinely. But you have to think further: why do they want to move to the United States and Canada? These people traveled thousands of miles on the sea to fight for more freedom for themselves and the next generation. I respect that spirit. It is their natural yearning for liberty: They don’t want to be suppressed by the Chinese society. What fault do they have?”

“I don’t know what the 200 immigrants will become in the future with my help, but I do know that they change their life because of me. I am great, right? If not for me, they couldn’t make any changes. My mission in the China Democracy Party is to connect every victim of the authoritarian government, not abandon them. I don’t think protesting in the Tiananmen Square is more noble than helping an immigrant settle down in the U.S. In my eyes there really is no difference. The only thing I know is that I can’t reject a person who wants to change his life.”

“On the evening of Saturday, March 21, 2020, in front of Times Square and the Chinese Consulate in New York, the 475th Jasmine Operation of the China Democracy Party vowed to eliminate the Chinese Communist Party virus that harmed Wuhan, China, and the human world!” Source: Twitter @juntaowang

Today, Wang Juntao still calls himself a “full-time revolutionist.” Whenever he is asked what his goal is, he answers, “I want to topple the Chinese Communist Party.” On Twitter, he identifies himself as “a Chinese citizen exiled in New Jersey”—he said he has obtained permanent US residence, but not US citizenship.

“I cannot make the vow. I cannot pledge that I’ll renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign state and be loyal to the United States,” he said. “The land that I care about is always China; the people that I care about are always Chinese people. I am Chinese.”

By the night of Feb. 8, 2020, Wang had led nearly 500 protests over the past 11 years, either in front of the Chinese Consulate, where people passed by without even glancing at Wang’s protesters, or on the Red Steps, where the cacophony of Broadway, the honk of the yellow cabs and the sirens of the cars of the NYPD drown the protesters out. During the protest that night, he stood with his camera at the front of the line, busily filming. Behind the demonstration, tourists were selfing, amazed by the giant billboards; by the faux Princess Elsa, Mickey Mouse and Statue of Liberty, vying for their attention. A circle of people watched street performers jump on and off from the steel bollards while some others listened to a rap battle.

Some time ago, Wang Juntao stopped describing these events as protests. Now he refers to them jokingly as “30-minute drills” to practice “showing guts.” The moment when the drill ended, the party members dispersed. They took off their white t-shirts, put away their navy caps, and disappeared in the crowd.

(Note: All interviews were conducted in Chinese and translated into English.)