Squeezed at the Margins

Struggling Artists in Rental Economy

by ZiQi Lin

Unit 706 is situated inconspicuously on the seventh floor of 20 Grand Avenue in an ordinary commercial building near Williamsburg. It has the same password-locked doors, the same gold-plated numbers, and the same plain concrete floors as many other office buildings in Brooklyn. Yet, in the city of dreams, the entrepreneurs in unit 706 represent a number of young arts organizations that are experimenting with survival strategies for artists and makers amid the brutal economic realities of sky-high rents and severe shortages of space.

1,300-square-foot photography studio

Inside, sunlight pours into the studio through the window panes. A pristine layer of white paint coats the walls. Bottles of hair spray litter the tables, photography equipment is scattered on the floor, and trendy coats hang on clothing racks. Throughout the day, filmmakers, photographers, dancers and models stream in and out of the white-box, all using the 1,300-square-foot space in their own ways.

In an office room next to the studio, three young women in their mid-20s sat on chairs they had bargained off Craigslist for free while conversing in rapidfire spurts. From reminiscing about the agonies of discarding empty beer cans to discussing the specifics of creating a new economic model, nothing seemed too insignificant or too impractical to wax lyrical about. Their WiFi password suggests their mission: artistsneedspace. They are the entrepreneurs behind Holyrad Studio, a creative agency that is pioneering an innovative community-based business model that serves local artists.

Holyrad’s team (from left to right): Saskia De Borchgrave, founder Daryl Oh, Elena Franco

Holyrad is emblematic of a crop of young arts organizations that are attempting to provide critical resources—from work and living space to equipment and exhibition opportunities—to New York City’s creative class. By providing affordable space and other shared resources, the mission of these entrepreneurs is to enable creative New Yorkers to stay and work in the city despite its harsh economic terrain. Others have formed craft communities in the quieter and more spacious destinations along the Hudson Valley, a commutable train ride away.

City mouse or country mouse, statistics are not on the side of these feisty young entrepreneurs. A US Small Business Administration report projects that around a third of small businesses with employees will not survive their first two years. Arts organizations are particularly vulnerable given the uncommercial nature of much of their work and the high costs of space rental. Nevertheless, these tight communities intend to forge a self-sustaining communal system of social and financial support.

Industry insiders point out that for many aspiring arts entrepreneurs, financial sustainability is somewhat dependent on the founder’s access to funds, often obtained through generational wealth or affluent networks. “For everyone else, the path forward is a bit murkier,” said Lauren Ruffin, chief external relations officer at Fractured Atlas, a company that provides business and technology support to artists. Her emailed message continued. “On a near-daily basis, we hear from artists at the brink of mental, physical, and financial crises, primarily attributable to their decision to locate their businesses in NYC. That being said, New York City is also home to thousands of artists and hundreds of arts support organizations working to ensure that the creative sector remains vibrant within the five boroughs. So, it’s a bit of a toss-up.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

Back in 2015, Daryl Oh left a monotonous job in the fast fashion business to become a freelance photographer, a career she soon found untenable, given the high cost of renting studio space. “It wasn’t sustainable,” she said. “I was barely able to survive, I didn’t have healthcare, I didn’t have savings and I looked at the path and I could just see that it was a plateau.”

It’s a problem she shares with 76 percent of New York City-based artists, according to a 2017 survey conducted by the Downtown Brooklyn Arts Alliance for CreateNYC. Taking cues from successes in the sharing economy such as Airbnb and Storefront, Oh shifted her attention to pioneering Holyrad on a membership model. Members pay a $300 annual fee which entitles them to rent the space at an affordable hourly rate of $35. They also have access to shared equipment rentals, “masterclass mixers” taught by fellow artists, and peer portfolio reviews.

The Art Vacancy, another fledgling organization, provides opportunities for artists to show and sell their work. Sáng Huynh, a Brooklyn-based curator, founded the organization in March 2017. “It becomes infuriating,” Huynh said, “because you want to sustain culture, you want to sustain society with the arts, but it’s difficult to do that when you are finding it difficult to make ends meet.” So far, The Art Vacancy has held six gallery exhibitions, including the first solo show of viral Instagram artist John Yuyi whose custom-made temporary tattoos explore how digital media and commercialization has influenced culture. Already an international phenomenon, Yuyi’s exhibition drew a flurry of press coverage from the likes of Forbes, Vogue Taiwan and i-D.

The Art Vacancy’s fundraising and brand launch party at Titan Studios in Nov. 2018

Lindsey Puccio is in charge of all event logistics for the organization, run by a group of six volunteers who have other employment. They meet at coffee shops or their own apartments. The organization has no office or dedicated exhibition or party space of its own.

“Everything in the world is stacked against us,” she said.

To cover the cost of exhibitions, which average about $3,000 each, Puccio said the group holds fundraising events to front the costs, hoping to recoup what they spent through ticket and beverage sales. Exhibitions typically lose money, Puccio said, but Art Vacancy is just about breaking even, helped significantly by friends-and-family discounts that cooperative suppliers have been providing. Long-term financial stability remains a distant vision. “We are set up as an LLC [limited liability company], but we function more as a non-for-profit in giving to the community,” Puccio said. “We are set up as a LLC because the process of getting 501(c)(3) [non-profit] status is absurd, and we need legal protection.”

Until now, The Art Vacancy has been operating without major financial backing. So far, its most effective strategy has been to stage exhibitions as pop-ups that last only a few days. “There were shows where we barely made it, and I mean nail in the wall at 8 o’clock. Installations are high-stress environments,” Puccio said. “Every exhibition has issues, but every one has been more planned than the next.” Usually, the team takes six hours to get a show ready, with everyone pitching in for everything from cleaning the space to hanging of artworks.

Members and friends of The Art Vacancy setting up the event

Other creative organizations rely on barter to help make ends meet. Such flexible arrangements and trading of services is prevalent among venue providers and creative organizations, as Kristina Cubero explained. She has a decade of experience as a freelance event producer and venue consultant in New York City. Venues, hoping for better digital exposure, will leverage the social media presence of artists who agree to hashtag or tag their spaces in exchange for discounted rents.“We barter all the time,” Cubero said, “because creatives really can’t afford it.”

Cubero cited three trends in the rental market: the increasing demand for co-working spaces, the growing need of venues to market themselves on social media, and the rise of very short term rentals for pop-up style events. Websites such as Splacer and Peerspace have streamlined the matching process between clients and event venues of every size and price range. Cubero said space is much more accessible than in the past, depending on how creative artists are in finding and using them.

As private studios become unattainable luxuries, artists have sought more creative and cost-effective ways of utilizing space. Painters set up canvases in their bedrooms; curators hold galleries in their apartments and dancers rehearse in their living rooms. Through photographs and video, Hotel Art Pavilion documents the work of artists by mounting very short-term shows, originally in locations such as hotel rooms, Airbnbs and other unexpected spots. Now, Hotel Art Pavilion has its own gallery space inside a garden shed in the backyard of the Brooklyn residence of two artists, Loney Abrams and Johnny Stanish. Apartment-style galleries are common.

While The Art Vacancy is a side project for a group of full-time professionals who work in related fields, Holyrad is a full-fledged business with salaried staff, now in its fourth year of operation. Its founder, Daryl Oh—Holyrad is her name spelled backwards—explained the breadth of her vision. “I think … that a lot of people in the mainstream don’t really see how we could be a great case study for the economic validity of the future,” she said.

“Because artists again have been compartmentalized as like a frivolous extra-curricular, but if you look back in history we are oftentimes at the vanguard of pushing social patterns and also cultural norms.”

One of the great ironies of ostensibly independent artists in the gig economy is how dependent they are on communities of supporting networks. By the end of 2018, Holyrad, for example, had nearly 400 individuals using its studio. This year, the firm introduced an annual membership model and 45 people have signed up so far. Occupancy rates have increased steadily, from 65% in January to 96% in March based on 12-hour work days. In March, 21 people used Holyrad’s Brooklyn studio for a total of 357 hours for 60 shoots, four rehearsals and three events. In fact, demand has become so great that last December, the company ran a Kickstarter campaign to raise funds for a second location. The result? $50,557 from 425 backers.

Elena Franco, an attorney by training who heads research and development for Holyrad, likes to quote American social theorist Jeremy Rifkin’s assertion that “The sharing economy is the natural child of capitalism.” She sees Holyrad as a manifestation of Rifkin’s work, “really, and a new model for a lot of different people to plug in.”

Saskia De Borchgrave, Holyrad’s operations and content director, dropped out of the film and television program at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts when she realized that the education she was receiving was not preparing her for the current labor market. She found that freelancing, where she could get experience and earn money at the same time, taught her much more than she was learning in class.

Instead, she turned to Holyrad’s Masterclass Mixers as her new information channel. “We have a masterclass every month—to see everybody share all of their information of how much they charge, like what platforms they’re using, how they’re getting their work out, what tools are they using, is just something that you don’t see at school,” De Borchgrave said, “and I don’t really know why it doesn’t come naturally at school for people to do that.”

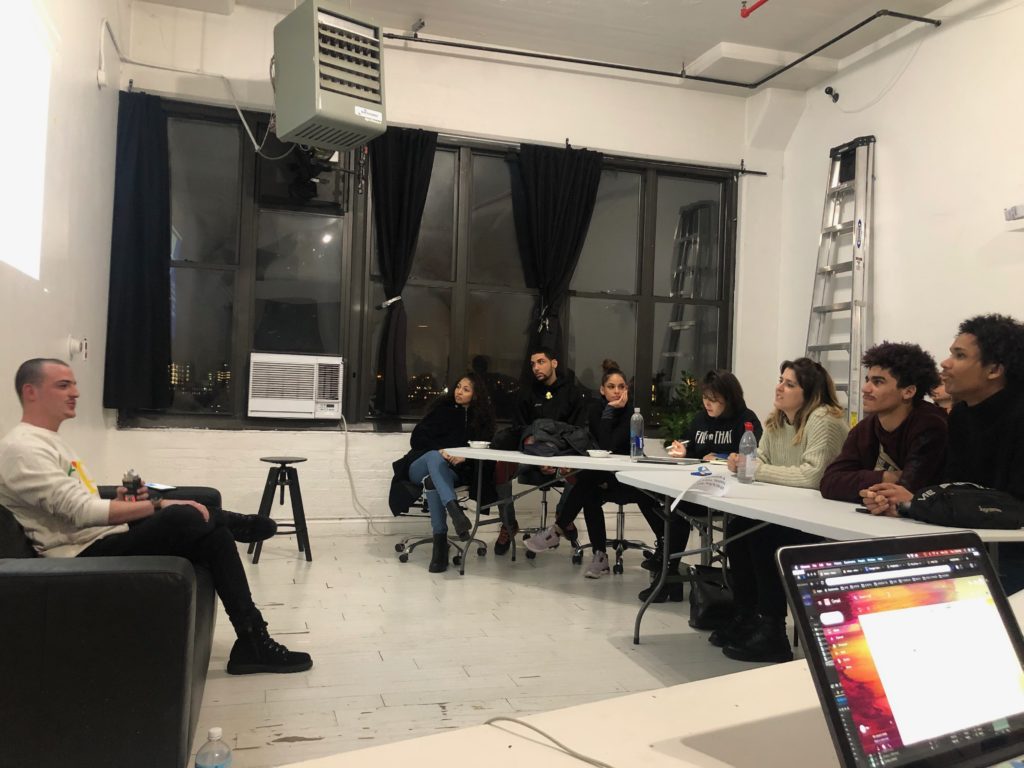

Holyrad’s Masterclass Mixer on Mental Health taught by Gregory Samus

Interviews with Holyrad’s members confirmed their enthusiasm for the project. Cole Witter, a photographer, said without this kind of backing it would have been impossible to “break into the game.” Before Holyrad, his only studio was his bedroom and renting equipment proved too costly. Another photographer, Clare Worsley, said the affordable space and equipment rental at Holyrad has enabled her to take on freelance clients more regularly. Membership in the community, she said, has saved her at least $2,000 a month.

Yet, Oh said providing affordable space for the artistic community cannot be an end in itself. Addressing the high cost of rent, she said, is like providing medicine to a symptom of the larger diseases of affordability and sustainability that plague society. “Our vision,” she added, “is an interconnected network of localized small spaces that are about accessing and bringing together a community around that space.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

When it comes to finding and holding onto affordable living and working space, artists can be their own worst enemies. The appeal of their arrival in a neighbourhood often lures in real estate developers who in turn attract the wealthy, setting off a series of gentrification effects. Aaron Shkuda, an urban historian at Princeton, outlined the process of artist-led gentrification in his book, “The Lofts of Soho: Gentrification, Art and Industry in New York.” He distills the complex progression of urban development into a simple three-step process: Industry moves out. Artists move in. Upper-income professionals push artists out.

In the 1960s, artists started moving into lofts in Soho, a light industrial neighborhood. Art galleries made their debuts and the upscale restaurants and boutiques followed. This drew in an upper-income demographic of residents charmed by the neighborhood’s bohemian appeal. But by the late 1970s, artists were being priced out and sought homes and studios in other parts of the city. Over the ensuing decades, according to Shkuda’s book, the phenomenon has repeated itself in locations like Bushwick of Brooklyn, in Long Island City in Queens and up the Hudson River in Beacon.

In the mid-1970s, with the city on the verge of bankruptcy, affordability and the overabundance of available properties was the calling card that drew in artists from around the country. Shkuda explained how artists of the period transformed Soho’s abandoned industrial buildings into living spaces, giving rise to the term “loft-style living.” The community of artists in Soho included household names of America’s arts scene, among them painter Chuck Close, composer Philip Glass, and choreographer Yvonne Rainer.

At the time, the city turned a number of abandoned buildings over to non-profit institutions. Back in 1972, Linda Blumberg and Alanna Heiss acquired the Clock Tower building in Lower Manhattan and started Clocktower Productions, a non-profit art institution that gathered multidisciplinary artists to work on experimental projects. Its corresponding radio station, Clocktower Radio, was one of the first all-art online museum radio stations.

What happened next is symbolic of the seismic shifts in the city’s real estate environment over the past five decades. Eventually the city reclaimed the property, which was a provision of the original agreement with the Clocktower, and sold it in 2013 for $160 million to real estate developers. The deal represented the largest sale of a landmarked property in New York City, now a luxury apartment complex now called 108 Leonard Street.

Tribeca’s iconic clocktower building has found a new name: 108 Leonard Street

The duo also co-founded MoMA PS1 in 1961 which was originally a dilapidated school building in Long Island City. Unlike the Clocktower building, MoMA PS1 remains standing as one of the oldest contemporary art centers in US. “The zeitgeist and tenor of the time was so much more cooperative,” Blumberg reminisced. Nevertheless, Blumberg cautioned against looking at the past through rose-colored lens. “There was no heat in the bloody building for two years,” said Blumberg.

“It is easy to become nostalgic about those times but being in a building with no heat for two years is not fun… We didn’t have the money to really renovate space.”

The artist and art journalist Gail Gregg reflected on the changes over time and their impact on the art community. “The fluidity of that time allowed the arts to really grow and blossom in this wonderful way,” she said, “And now it’s just such a different environment for artists and it affects the art.” She pointed out that the lack of a studio space has altered the kind of art that is produced. “It has a consequence on the work … I used to tell people I make shopping bag art. Because it had to be able to fit in a shopping bag so I can take it to shows and things like that,” Gregg joked. “Because honestly, having a studio at home where you have to put things away and get them back out, it’s a disincentive to work. The ideal situation is a big place, you can make messes, you can be working on something, you can leave the fresh paint, close the door and walk out.”

For many artists, space where brushes can be left to soak is far out of reach. Generally speaking, more than half of all renters are cost-burdened, which means they are spending more than 30 percent of their gross monthly income on rent. For cash-strapped artists, that figure is more than double. It’s typical for artists to spend an average of 65% of their income on rent, according to a 2013 Spaceworks survey.

Taezoo Park does slightly better than average, depending on fluctuations in his income. The Brooklyn-based artist breathes new life into abandoned parts of technological gadgets and turns them into “digital beings.” His monthly expenses average between $2,500 and $3,000, of which he said he spends about half on living and studio rent. His main source of income comes from his work as a freelance technician, which includes maintaining the art pieces of the renowned video artist Nam June Paik. Park’s own work includes his interactive series, “Singularity,” a colorful coagulation of buttons, wires and sensors which can easily be framed and hung onto any wall. When spectators interact with the works that are embedded with motion and noise sensors, the pieces light up and seem to come alive. In 2018, Park sold 12 of these eight-inch-by-eight-inch pieces at $1,250 each, which helped him clear his credit card debt.

Taezoo Park’s artworks from his Singularity series

Real estate remains the most gigantic hurdle for creatives. A 2015 report by the Center of Urban Future titled Creative New York found from 150 surveys conducted with curators, filmmakers and donors that nearly everyone cited real estate prices as the greatest threat to New York City’s cultural landscape. It further cited the gentrification-induced closings of at least 24 music venues and 310 art galleries between 2011 to 2015. Since 2005, the report counted 22 performing arts theaters that have relocated or shut down because of soaring rents and changing neighborhood characteristics.

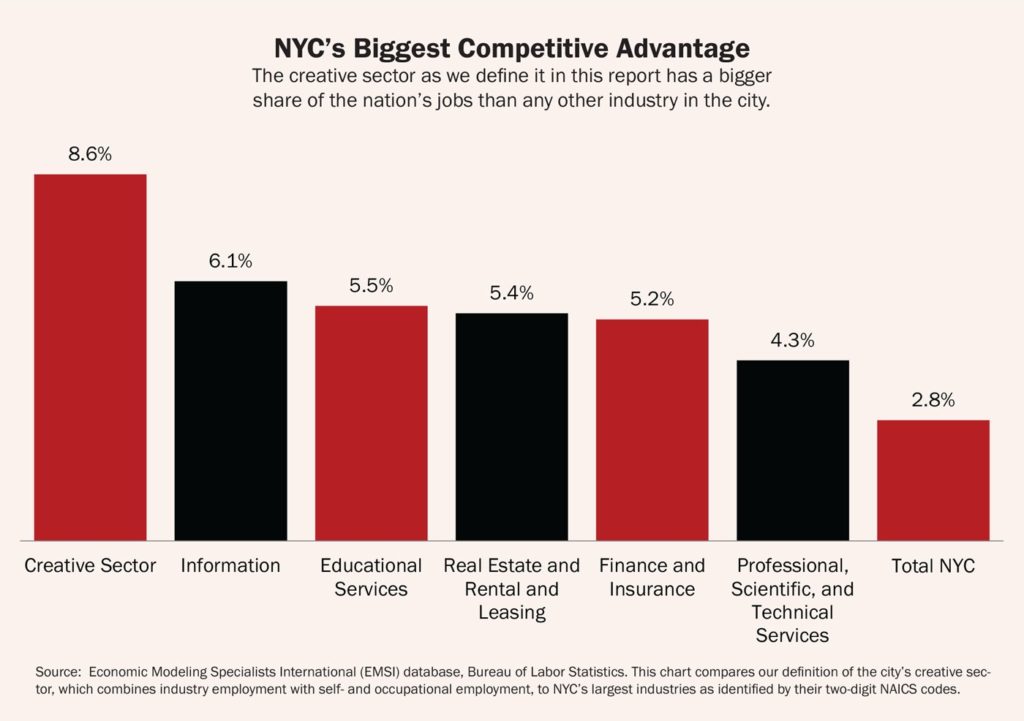

Such alarming figures not only signal harm for New York’s cultural vibrancy but they can mean damage to the city’s economic edge. The report further argues that the creative sector is the source of New York’s greatest competitive advantage. In 2013, the city’s creative sector employed nearly 300,000 people in the fields of advertising, film and television, broadcasting, publishing, architecture, design, music, visual arts, performing arts as well as independent artists.

At the same time, however, the report highlights much to be optimistic about in the local arts scene. Of the city’s 20 largest industries including real estate, finance and educational services, New York’s creative sector comprises the largest share of all national jobs. From 2003 to 2013, the report stated that New York City’s share of the national creative workforce increased from 7.1% to 8.6%, which is much higher than the city’s 3% share of all jobs in the nation. The numbers include large commercial firms, like ad agencies, that conduct creative work.

Source: Center of Urban Future’s Creative New York report

In “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” the author Jane Jacobs, explains the importance of encouraging mixed-use districts, and the intellectual and creative sparks that fly when people of different incomes, races, occupations and education levels come together in the same neighborhood. Urban theorist Richard Florida further elaborates on this concept in his now-controversial book, “The Rise of the Creative Class,” where he asserts that the “technological and economic creativity are nurtured by and interact with artistic and cultural creativity.” Creative activities have spillover effects on other fields through a process of “cross-fertilization and mutual stimulation” because they share similar thought processes.

Florida first coined the term “creative class” in 1998 in a study which found that high-technology professionals make location decisions based on lifestyle interests rather than employment choices. He popularized the concept of artist-led urban development, encouraging cities to attract human capital through soft cultural policy instead of hard infrastructural ones. “The ultimate intellectual property – the one that really replaces land, labor and capital as the most valuable economic resource,” he said, “is the human creative faculty.”

Creativity has since transcended the narrow boundaries of arts and culture into the realms of business and technology. It is now enshrined as one of the most valuable skills to possess because it is a source of economic value and intellectual currency. Contemporary media websites and publications echo this sentiment. “Creativity Is The Skill Of The Future,” declares an article on Forbes. “Why Creativity is the Most Important Skill in the World,” announces a blog post on LinkedIn.

Despite the creative spillovers and multitude of services that artists and developments bring to the neighborhoods they inhabit, local communities have become increasingly hostile towards attempts to hipster-ize their spaces, objecting to the way it exacerbates gentrification and perpetuates inequality. The economic revitalization plan of introducing art galleries and espresso bars to draw young creatives and tech workers seem to have worked too well, but only for a middle class that was already somewhat prosperous.

In fact, cities with the highest levels of wage inequality are also those with the most developed creative economies. In his 2017 book titled “The New Urban Crisis,” Florida acknowledged the ills of urban development by shining a spotlight on how cities are “increasing inequality, deepening segregation, and failing the middle class.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

New York City has made some efforts to redress the difficult housing plight of artists through its Affordable Real Estate for Artists initiative. In 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio promised to create 1,500 units of affordable housing and 500 units of artist workspaces for New York’s creative workers over the next decade. “The CreateNYC cultural plan addresses affordability as a crucial factor in attracting and maintaining a diverse and thriving community of artists in New York City. The Affordable Real Estate for Artists initiative, one way the Department of Cultural Affairs supports NYC’s artists, uses a number of models to create and subsidize affordable artist workspace. Expanding access to studio or rehearsal space creates stability, flexibility, and community for the artists and creative workers that help make our city’s cultural landscape unique,” read the statement from Department of Cultural affairs.

Collaborating are the Mayor’s Office, the Housing Preservation and Development agency and the New York City Economic Development Corporation. The approach involves $30 million in capital funding from the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs to convert underutilized city-owned spaces for artist use. A that was completed recently is ArtBuilt Brooklyn, which is funded with private and public support under an affordable real estate initiative. It has opened up 50,000 square feet of workspaces to roughly 100 artists at the Brooklyn Army Terminal. So far, over 200 units of artist workspaces have been completed, with another 350 in the pipeline, including the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Arts Center on Governors Island.

Other similar projects include Spaceworks, which provides subsidized studio rentals across the five boroughs. It was set up in 2011 as an initiative under the Department of Cultural Affairs. It currently has five locations including Williamsburg, Park Slope, Gowanus, Long Island City and South Bronx that offer rehearsal, art studio and co-working spots for artists.

New last October as a means of providing a cushion of community support is Freelancers Hub. The Freelancers Union partnered with the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment to make New York the first city in the country to provide direct services to support independent workers in creative industries. Data from the Department of Consumer Affairs indicates that more than 400,000 residents of the city’s five boroughs are self-employed and that nearly half of Freelancers Union’s 375,000 members are based in New York City. The Freelancers Hub provides free coworking space to independent professionals four times a month, as well as workshops, training, legal clinics and tax and financial guidance.

Coworking space at Freelancers Hub

The City is injecting more resources to support its future workforce because the growth of the gig economy has created opportunities but also raised concerns about job stability and financial security. In 2017, the Freelance Isn’t Free Act – the first law of its kind in the country – was implemented in New York City to solve the common problem of late payment or nonpayment especially since 38% of workers in New York City are independent workers. Professionals in the arts are particularly vulnerable to such exploitation as 72% of complaints that Department of Consumer Affairs received in the first year were from filmmakers, designers, producers, performers, artists and the like.

Artists like Alexandra Jacob, 36, have found ways to continue to go it alone. She is a full-time ballerina whose freelance projects range from photography shoots to performance art pieces, with a recent featured collaboration with Kanye West’s Yeezy Season 7 campaign advertisement that was plastered across newspapers and billboards. Prior to going freelance in 2014, Jacob spent a decade as a company member of The Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Dress rehearsal of Michel Fokine’s 1905 ‘Dying Swan’ for Jacob’s performance with nonprofit group Wide Rainbow.

During her initial years as a dancer in New York City, she juggled multiple full-time jobs, from Starbucks barista to restaurant waitress, to support her career. When she first arrived in the city, a friend introduced her to Centro Maria Residence in midtown which is run by Catholic nuns. It granted little privacy but the residence provides affordable housing for women with international backgrounds who come to live or work in the city. The rooms cost $215 a week for a triple share to $250 a week for a private room and the residence provides breakfast and dinner. It is a home of choice for many student and professional dancers.

Demanding touring schedules often make it hard for dancers to hold on to second jobs, so Jacob came up with other ways to generate income. She experimented with running a side business on eBay reselling designer bags she had thrifted. “It was fairly lucrative,” Jacob recalled. “I think my most successful sale was reselling a Chanel wallet for $550 or so that I bought at Goodwill for $1 on senior citizen day with my grandma.”

Despite all the private, public and self-styled efforts, demand for affordable housing and studio space still vastly outpaces supply. Refuges like Centro Maria, for example, are a transitional solution and only for a few. In 2015, the Minneapolis nonprofit Artspace opened its first New York City project at PS 109, a former East Harlem elementary school. The spacious studios went for as low as $494 a month and two-bedroom apartments were priced at $1,022 a month. A whopping 53,000 people applied for the chance to lease one of 89 new affordable housing units, making the 0.2% acceptance rate lower than Stanford’s. Similarly, 218 visual artists applied to participate in the lottery for three available spots at the Williamsburg location of Spaceworks. The Smack Mellon artist studio program which provides artists with a free private studio space draws in more than 700 applicants each year. Only six applicants were selected for the 2018 to 2019 residency program.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Newburgh is 60 miles north of New York City along the Hudson River, a city that faces drastically contrasting problems from its cosmopolitan neighbor. The Center for Community Progress, estimates that roughly 30,000 residents live within its 3.6 square miles, 60% of whom are people of color. An estimated 30% of local families and 40% of children in Newburgh live below the poverty line.

Despite the city’s past glories—George Washington was headquartered in Newburgh—a history of poor policies and economic collapse have left it marred by crime, poverty, corruption, and a glut of vacancies. In 2016, a study by the Center for Community Progress put the number of vacant properties at 780, most without roofs or all four walls and ridden with lead or asbestos issues. Community resistance has hindered rehabilitation as the memory of an urban renewal project in the 1960s still stabs. It involved the bulldozing of more than 1,000 buildings in a predominantly African-American neighborhood.

Newburgh’s affordability, however, has brought New Yorkers, including artists and makers, to resettle in the smaller city. In fact, demand in some parts of town has become so pronounced that city planners say they are on the brink of a gentrification crisis, which further complicates the ethical and financial aspects of developing and reusing vacant properties.

Luke Ives Pontifell has grand plans to be a part of Newburgh’s economic revival. Pontifell sports round wire-rimmed glasses and appears immaculate in a suit and tie combination that exudes an aura of scholarly aristocracy. He founded Thornwillow Press in 1985 when he was 16 and has since grown his business into a global leader in the publishing of handcrafted, limited edition books. Thornwillow is named after the 18th century farmhouse in Massachusetts where Pontifell grew up. Its publications have appeared in the permanent collections of Harvard University, the White House and the Vatican Library. Realizing his responsibility in teaching and perpetuating the arts and crafts of the written word, Pontifell founded the Thornwillow Institute in 2015 as a nonprofit with the mission to promote craftsmanship.

Luke Ives Pontifell, founder of Thornwillow Press

“What evolved out of that is this idea that craft and art coming together around culture can change a community and it suddenly became this catalyst for urban revitalization,” Pontifell said. “The idea is that it is no longer just the written word and the art of the book, but it’s craft and all its forms whether you are a carpenter, a woodworker, a weaver, a web developer, graphic designer, typographer, an architect, a designer.”

He envisions the creation of Thornwillow Makers Village to be a community that provides artists who are moving to Newburgh with maker studios and fellowship residencies.

“The flipside of this exodus of artists and makers coming here is the artists and makers who are in turn leaving Brooklyn and leaving New York as they are driven out by high prices or lack of space and opportunity… to me that’s undesirable development, that the people who made it so great can no longer afford to live there,” said Pontifell.

The first phase will costs $2.5 million as the amenities he plans to build include Newburgh’s first bookstore café in fifty years, a classroom lab and gallery and event space. Of that, roughly $2 million is for renovations. In September 2018, the project was awarded $400,000 in New York State economic development matching funding by the Mid-Hudson Regional Economic Development Council. Nevertheless, Thornwillow still has to raise roughly $1.3 million dollars from foundations and individuals to fund the makers village.

To raise funds, Pontifell is publishing a limited-edition copy of The Great Gatsby with covers made using genuine engraving. So far, he has raised more than $130,000 from over 400 backers on the Kickstarter campaign. “Once it’s up and running, we don’t want this to be something where we have to go back to people every year and ask for money… It has to be a self-sustaining entity,” Pontifell said. He sees the main driver of the revenue stream as rentals from studio and apartments, profits from the bookstore, and income from a large hall that could potentially become a marketplace or screening location.

The whole village is planned to occupy 100,000 square feet. Rental rates are roughly a dollar per square foot per month. Currently, a carpenter who rents an estimated 2,000-square-foot studio pays $2,500 while a weaver who rents an approximately 500-square-foot room foots $500 monthly. “In order to allow for a creative community, a maker community, one also has to have these related opportunities to live, to work and to play affordably,” he said, “but beautifully and imaginatively and conveniently.”

Luke and his wife, Savine, initially made the decision to move to Newburgh out of similar considerations. Savine drew a one-hour radius circle around their New York City apartment and eventually pinpointed 25 Spring Street in Newburgh as the new location for Thornwillow’s printing operations. “We needed a lot of space to do our business and room to grow. We need it to be close enough to Manhattan so that someone can come up on a day trip… and it needed to be affordable.”

Thornwillow’s main production area is crowded with numerous letter presses and engraving machines. A young man spins the metal wheels of a rusty machine and a young lady bounded books on the floor above while rock music blasted in the background. The Pontifells are engaged in furious discussions with their eyebrows furrowed. They debated intensely about the size of a dot, the intensity of a stroke and the inches of a margin.

A young employee operates the machines

To the Pontifells, Thornwillow is a belief, an idea, a movement. “I believe that how something is made, who makes it, the people behind the object become part of it, and that object then becomes an object with a soul,” he said. “Today there’s a reaction to technology, in all of these instances there is a dehumanization of the quality of the life. That reaction has been consistently the same. This return to craft, this return to things that are made by human beings with care.”

Next door to the press on Spring Street is Atlas Industries, an architecture and furniture design firm—with 55,000 square feet of space—that also rents out commercial studios to small creative businesses. It currently rents workspaces to 42 tenants of different arts and entrepreneurship backgrounds including graphic designers, bookbinders and musical equipment technicians, and has a long waiting list. A 200-square-foot space would go for $350.

The company was based in Brooklyn for 22 years before its move to Newburgh in 2013. “The financial aspect is certainly a part of it, but there’s a lot more to it,” said co-founder Joseph Fratesi. “There’s no integrity to it [the city] anymore.” Recalling a time when the Lower East Side was full of artists paying cheap rents, Fratesi now considers much of the city a theme park for the wealthy. “Now, it’s like the entire city has been blanketed. There is no neighborhood like this anymore. There is no place to go.” Instead, Fratesi and his partner Thomas Wright looked north to transplant their company. When they saw Newburgh, they were stunned by its city environment, racial diversity and beautiful architecture. “There’s a real sense of grit and spirit that was really fading from the city at the time.”

Joseph Fratesi, co-founder of Atlas Industries which offers studio rentals to Newburgh’s creative community

Vincent Cianni, a documentary photographer whose works explore community and social justice issues, rents a studio from Atlas Industries. He expressed similar views.“I find Newburgh is as dynamic a place as Williamsburg was in its formative years,” he said. “I’m not against revitalization as long as it involves everyone … I wouldn’t live in a place like Williamsburg today because it displaces people without taking into consideration its history and culture.”

Lori Grinker is a photojournalist and an adjunct faculty in the journalism department at the New York University. She is a newer member of the Newburgh arts community who is still renovating her new apartment. “I lived in New York my entire life and paid really cheap rents. But there’s barely any place left. Everything is gentrified,” Grinker said. She found Newburgh quieter and more spacious, a place that allows her to focus on her work, unlike the city where there is always something to do.

Nevertheless, as Gail Gregg pointed out, relocating to places like the Hudson Valley greatly reduces access to buyers and the arts market. Crafts businesses that have a loyal base of digital customers will find it easier than those in the fine arts, she said.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Linda Blumberg recently stepped down after 11 years as the executive director of the Art Dealers Association of America. “It’s hard to know if the city will completely price itself out,” she said. “It’s just hard to know [whether] New York City will sustain its arts community. But am I optimistic? I am, because I think this is a city that has always attracted people to come to it.” In her view, its abundance of opportunities in the arts, the diversity of its population, and the presence of intellectual resources will solidify New York’s longevity as an arts hub. “I believe it will figure out a way of sustaining itself… I don’t see it going away,” Blumberg said. “It has vibrancy, a continuous inflow of new people, new ideas. That really is strength.”