Invisible Violence

LGBT Victims of Abuse

by Emma Rudd

In the first weeks of her freshman year at a small liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, Emma Madeira broke up with her high school boyfriend, joined the softball team as a catcher, and landed a date with a well-known junior. It was all part of a plan to do her own thing in college. Like many 18-year-olds newly released from parental and religious restraints, Madeira was eager to explore life on her own.

Now 26, Madeira looks nearly the same as she did at college graduation, with short brown hair, a wide smile, and a needle-sized gap between her two front teeth. Her naturally tinted round cheeks give off a ever-cheery impression. She’s talkative but not to the point of excess and, almost always, there’s enthusiasm in her voice. She paused at the thought of her college self before remarking sarcastically, “I’ve changed so much.” With a hasty laugh, she began to rattle off a few notable details from those early years of adulthood. Her roles as softball captain and residential adviser during junior and senior year, the campus she found too small, its notorious divide between student athletes and non-athletes, and the relaxed rules that invited a constant stream of weekend parties.

There are, of course, details that can’t be telegraphed in fewer than ten words. Madeira hesitated before she explained that the date she had with the well-known junior in her first weeks as a freshman soon evolved into a relationship that lasted nearly three years. Now, five years after the breakup, she matter-of-factly described the course of the relationship as if she had catalogued all her memories and neatly organized them into separate files. There was the controlling behavior. Madeira’s partner disapproved of her going anywhere alone and when they did venture out, they remained strictly within the same social circle. Her partner pressured her to spend nearly every night for the three years they were together in the same bed, rarely her own. Soon, the violent behavior started. During fits of anger, her partner would yell at her, stand inches from her face and throw things at her. In the last year of their relationship, there were several instances of sexual coercion. Madeira said that at times when she was intoxicated or emotionally distraught, her partner would insist on engaging in sexual activity. “I didn’t know how to date anybody,” she said. As an 18-year-old, “I thought maybe a lot of this stuff was normal.” Now, she understands that the behavior was abuse.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention defines intimate partner violence under four main categories: sexual violence, stalking, physical violence, and psychological aggression. Most people in the United States are familiar with how these categories can materialize in romantic and sexual relationships. This year alone, a husband murdered his wife, a first grade teacher, in the final days of their divorce proceedings. A high-power CEO forced a cellphone from his wife’s hands despite her screams. And a popular R&B singer was accused of imprisoning and controlling women whom he referred to as “girlfriends.” Madeira’s experiences could easily be positioned among these better known stories as just another example of the many forms intimate partner abuses can take. Nonetheless, lumping her in with all the headline-producers obscures the complexities that make her account unique.

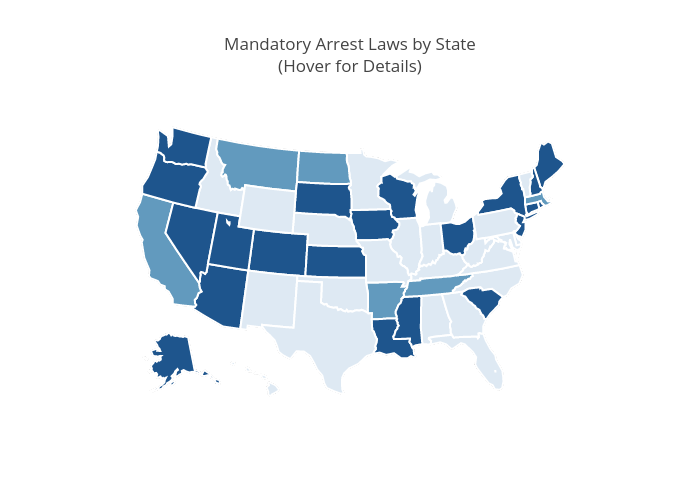

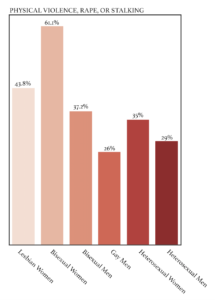

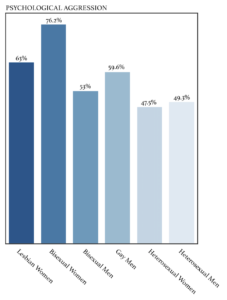

Madeira identifies as queer. Another woman, a popular classmate who served as softball captain the year Madeira joined the team, perpetrated the abuses of her college relationship. She is not unlike the thousands of LGBT-identifying adults surveyed by the CDC in 2010 on intimate partner violence by sexual orientation. The study estimated that 43.8% of lesbian women in the United States have experienced physical violence, rape, or stalking in their lifetime along with 61.1% of bisexual women, 37.3% of bisexual men, and 26% of gay men. With the exception of gay men, these numbers far surpass the 35% of heterosexual women and 29% of heterosexual men who are said to have experienced the same violence. The same survey estimated that 63% of lesbian women have at some point experienced psychological aggression by an intimate partner, in addition to 76.2% of bisexual women, 53% of bisexual men, and 59.6% of gay men. A lesser 47.5% of heterosexual women and 49.3% of heterosexual men, on the other hand, were found to have been victims of the same sorts of abuses.

Source: CDC 2010

The CDC’s findings outline a clear discrepancy in the rates of all forms of intimate partner violence among LGBT-identified persons and those who identify as heterosexual. Dr. Adam Messinger is a professor at Northeastern Illinois University who specializes in research on the topic. He confirmed that intimate partner violence occurs at higher rates among those who identify as sexual minorities. Similar studies, such as Williams Institute’s and that of the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs repeatedly come to the same conclusion.

Still, prevailing representations of intimate partner violence are overwhelmingly heterosexual. The small size of the LGBT population may, in part, account for the disproportionate inclusion. Gallup estimated that 4.5% of adults in the United States identified as LGBT in 2017—a number that has steadily increased since a 2012 estimate of 3.5%. One suspected cause of this statistical rise is increasing comfort of individuals over time with publicly identifying as a sexual minority. Millennials offer the highest rates of LGBT self-identification at 8.2% of total respondents while older generations like Baby Boomers and Traditionalists stagger behind at 2.4% and 1.4% respectively.

Implicit in these numbers are the harsh and often violent forms of discrimination against the LGBT community that have historically kept its members away from the public sphere. Reports of raids, beatings, and burnings against LGBT-identified persons are likely a leading cause of the discomfort older generations feel about publicly identifying as a sexual minority. But millenial’s increased willingness to identify is not to be confused with fewer acts of violence. Despite expanding legal and social recognition in the US and abroad, similar hate crimes persist alongside a narrow understanding of what it means to be in an intimate or romantic partnership. On-screen representations of LGBT couples, for instance, are still vastly outnumbered by heterosexual romances. For the few that do make it onto the big screen, intimate partner violence is never a story line.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that allegations of spousal violence and abuse entered the legal and social mainstream as representative of a systemic problem. Thousands of women across the US championed the introduction of hotlines, crisis centers and shelters, laying the groundwork for contemporary movements against domestic violence. Much of what we understand today about how violence occurs in romantic and intimate relationships can be traced back to this grassroots activism. But it had its limitations. For one, same-sex marriage was illegal at the time and national public opinion on those who identified as gay or lesbian—predating the inclusion in polls of identifications like bisexual and transgender—reflect a society struggling to acknowledge the validity of same-sex unions. As a result, Dr. Messinger said, “it oftentimes seems that the laws, policies, services and interventions have been focused on how we can help female survivors of different-gender intimate partner violence. Now where does that leave survivors who don’t conform to this stereotype?”

Sophie Kase was left wondering if her experiences were even worth sharing. Phone calls and messages from her ex-fiancé threatening self-harm or even suicide would often interrupt her work day or outings with friends. Panicked, Kase would comply with her fiancé’s demands to come home, slipping away from whatever she was doing at the time with little explanation. There were also fights that turned physical; the rooms her partner locked her in to prevent her from leaving; the recurring non-consensual sex. One night, after she announced she was leaving, her fiancé tried to strangle her. She was too uncomfortable to divulge the abuses of her five-year relationships with close friends. “The initial worry was that I wouldn’t be taken seriously. If it was a heteronormative relationship I wouldn’t have been as hesitant about sharing any of it because that’s more of a norm.” At 24, Kase works as a transfer credit analyst at a university in Ohio. Memories of trauma remain close. She met her ex-fiancé while attending the university where she now works and, when we spoke, it was just over three months since they had separated. She recounted the events of her abuses with a hasty confidence. Her quick sentences would often ebb into silence before continuing with renewed speed. After a while, these pauses seemed intentional, designed to create distance, as if she were placing space between herself and the too-near memories.

The halting flow of Kase’s recollection was similar to others I interviewed. Sawyer Rohlin, who identifies as transgender, scattered the details of his former relationship with comparable lulls. Only now, they implied a hesitancy on Rohlin’s part to label anything he experienced as abusive. When he described the night his boyfriend of two months sexually assaulted him while he was sleeping, the 17-year-old swiftly added “it could have been a lot worse, I understand that.” The relationship lasted another month but feelings of guilt and shame pulled at Rohlin and remained long after the breakup. “I always wonder why I didn’t say anything,” he said. “I guess I didn’t blame him for what he did. I can talk about it to friends now but still, the idea of confronting him seems completely impossible.”

To recognize an occurrence of intimate partner violence and then to disclose it to others is difficult for any survivor, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity. As both decades of scandal in the Roman Catholic church and the #MeToo movement have revealed, accounts of sexual abuse and violence often lie dormant for years, even the better part of a lifetime. Newly unearthed tales of nonconsensual sexual activity, verbal harassment, physical violence, and psychological aggression have occasioned waves of empathy alongside revived efforts to expand preventative practices and victim services. Even in the current, more inclusive atmosphere, LGBT relationships have been predominantly ignored, pushed to the side by those who readily fit into more recognizable formulas of abuse. Without models or examples, LGBT victims of such violence may be less equipped to label their experiences as abusive. This is especially true when the forms of abuse coincide with their sexual minority status.

For Madeira, coming out as queer so soon after leaving home for college left her particularly vulnerable to her girlfriend’s influence. In retrospect, Madeira said, “I think she picked me out as someone who was in a space to be emotionally manipulated.” She was three years older than Madeira, captain of the softball team, and prominent member of the on-campus Gay Straight Alliance, just the type of mentor Madeira wanted to start building her new life as an out queer woman. Her girlfriend first approached Madeira after she came out to her teammates with advice on how to navigate LGBT life on campus. Madeira was thrilled with the offer and what originated as friendly counsel quickly evolved into a deeply emotional romance in which the power imbalance never changed.

For the next three years she offered Madeira entry into the close-knit LGBT campus group. She included her in the upper class social activities of the softball team. She even helped steady Madeira’s precarious sense of self. In her own words, “it felt good to be recognized. People thought that I had a really solid sense of my identity because we were together and she was really out.”

At the same time, however, and for the next three years, Madeira said her girlfriend controlled every person she hung out with. She was left with few social networks that did not emanate from her girlfriend’s pervasive influence. When she did spend time alone or strayed from her girlfriend’s control, her girlfriend would chastise her and at times bombard her with screaming fits and flying objects. “She said that if I was away from her I would do bad things,” Madeira said of the extreme reactions. The level of control left Madeira with few outlets on campus to discuss her deteriorating relationship.

Off-campus support became just as scarce. Although Madeira grew increasingly comfortable with her sexuality at college, she remained reticent about sharing her new life with her friends from home. Only a couple of her closest high school friends were aware of her sexual orientation. Eventually Madeira came out to her deeply religious parents, telling them of her new college relationship. They struggled with the news but were accepting to a large extent, just not of Madeira’s girlfriend. “For obvious reasons,” she said. Yet, her girlfriend interpreted this to mean that her parents didn’t like the fact that Madeira was queer and began limiting her communication with them and discouraging her visits home.

Intimate partner violence is, of course, intimate. The ways in which patterns of violence and abuse manifest in any relationship depend on the many personal features of an individual’s life. But certain conditions—financial insecurity, having a child at a young age, and educational disparity between partners—are risk factors, known pressure points, for victimization. Sexual minority and gender status have only recently made the list.

Dr. Lori Girshick is a long-time domestic violence activist and author of Woman to Woman Sexual Violence. She stressed the impact that widespread social biases can have on LGBT experiences. “There’s still a significant portion of our population that believes it’s unnatural or sick to be LGBT,” she said. These beliefs are then coded in laws, disseminated covertly in religious and public education, or infused into the very practices of service providers meant to aid those who have experienced violence and abuse. These beliefs can influence a victim’s ability to seek help, formally or informally, or can contribute to a sense of inadequacy—the feeling that one’s experiences are not serious enough to share—like that of Kase’s discomfort with confiding in her friends or Rohlin’s reluctance to use the term “abusive.”

But fundamentally, these beliefs establish a troubling social landscape. To publicly identify as LGBT can still mean to be relegated to the rank of undesirable and forgotten. Such a ranking has the power to negatively impact self-esteem, mental health, job opportunity, access to medical care, and familial support among others. In short, it can leave those who identify as LGBT more vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. In Madeira’s case, she was just as inexperienced in dating as most of her peers. Having just come out at the start of her college years, however, was an added pressure that left her highly susceptible to her girlfriend’s manipulation. Anxiety over disclosing her sexuality, stress about where she would fit, and the strains of her family relationships tipped the scales and her girlfriend took advantage of the imbalance.

Among broad definitions of intimate partner violence like the CDC’s, psychological aggression is the category most varied in definition. Dr. Messinger said that a common tactic in abusive LGBT relationships is to threaten to expose a victim’s gender or sexual minority status to those from whom the information has been kept. The potentially dangerous outcomes of a forced outing make this tactic especially effective. Fear of family disownment, public ridicule, and violence may stun victims into staying or not reporting the abuse. Abusers have also been found to force their partners to stay closeted so that their own sexual identity can remain hidden. The harm of secrecy can be felt in both cases. “If you can’t tell anyone you’re in a relationship, how can you tell anyone that you’re being abused in that relationship?”

Other aggressions might include accusing a victim of not “really” being gay or lesbian. Or, in the case of bisexual victims, telling them that they should just choose. Along the same lines, abusers may make victims feel ashamed of their sexual orientation, following a well-known rhetoric of intolerance. Other times, they might blame victims for their own sexual minority status by claiming that their partner “turned” them gay. Brian Tesch, whose research centers on domestic violence in the LGBT community, said that transgender victims face particularly unique forms of aggression. “If your significant other is destroying all of your hormones, wigs, or medication, that’s a form of abuse that isn’t really going to be understood by most,” he said. Tesch is a doctoral candidate at Mississippi State University. He also noted the harm in using the wrong pronouns or referring to the victim by biological sex rather than gender identity.

The question that arises is “why stay?” When confronted with this, Kase let out a deep sigh before withdrawing into another brief silence and then offering her best explanation: that acknowledging the relationship’s failure would undermine the fight for recognition of LGBT couples in general. “Everyone has been trying so hard for marriage equality and equal rights,” she said. “You don’t want to give in to society and anyone else that has had doubts about your relationship.” So for fives years, Kase forced a smile in public, hoping it might conceal the slew of abusive behaviors she experienced in private. It wasn’t until close friends took notice of her frantic comings and goings that she opened up about the abuses. Still it was with hesitation. “I didn’t want this to be another failure for myself,” she said.

Kase’s concern over how her relationship might be perceived is not unreasonable. One can only imagine the possible hate-strewn responses. Phrases like “homosexuality is an abomination” and “you’re going to hell” come to mind—standards for most anti-LGBT demonstrations. Dr. Girshick noted that implicit in these retorts is a belief that these couplings represent a revolt against the natural order of partnership and are therefore destined for failure. Madeira’s parents implied something similar when they told her things may have been different in her college relationship if it had not been with another woman. While they weren’t carrying picket signs and shouting of Leviticus 18:22, the underlying message is eerily similar. And it hasn’t stopped short at familial disputes.

![]()

It wasn’t until 2015 that same-sex marriage was ruled legally legitimate across all 50 US states. Prior federal and state laws, passed as recently as 2004, defined marriage as exclusively between one man and one woman. As the push for equal rights gained traction, lawmakers overturned statewide bans on same-sex marriage, leading to the landmark 2015 Supreme Court ruling. A 2018 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center found that national approval of same-sex marriage has steadily increased from 37% in 2007 to 62% in 2017. While these numbers signal societal change, it’s unclear how further legal challenges will play out. Many policymakers are either unaware of how to address the specific needs of the LGBT community or altogether indifferent. Experts have pointed to religious exemption laws, which allow business owners, adoption and foster care services, and psychological counselors, among others, to discriminate against those who identify as LGBT. Cake controversies are perhaps the most publicized example of how these laws can disrupt the everyday life of an LGBT-identifying individual.

For survivors of intimate partner violence, the laws themselves are often the impediment. Juliette Verrengia is a policy advocacy specialist at the New York City Anti-Violence Project, a position she accepted last May after receiving a master’s in social work at the City University of New York. She said that laws and policies meant to combat domestic violence—the legal world’s sibling term for intimate partner violence—are more often than not created with only heterosexual couples in mind. The issue for the LGBT community, she said, is people “trying to make members of the community fit into a binary that doesn’t serve them.”

The results usually fall somewhere between inclusivity and inattention, along the lines of the 1994 Violence Against Women Act. Originally introduced through the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement bill, the Act sought to expand criminal justice responses to incidents of domestic violence and sexual assault, making it the first federal legislation to declare such acts as crimes. Yet, if the name is any indication, despite its groundbreaking achievements, the Act was limited to addressing violent crimes perpetrated against women. In addition to law enforcement expansions, it offered the first federal funding for community-based responses to domestic violence. Grants were distributed nationwide across institutions like non-profit organizations, schools, and state governments working to implement victim services and preventative programs. A staggering decline in overall rates of domestic violence has brought forth four reauthorizations since. A 2012 study released by the US Department of Justice found the drop to be as great as 64% among men and women age 12 and older between 1994 and 2010. But even in the face of such success, its 2013 reauthorization proposal was met with Republican opposition on the grounds that it would extend the Act’s services to same-sex couples and allow battered illegal immigrants to acquire temporary visas. The Act was eventually renewed with provisions for LGBT, immigrant, and Native American victims of domestic abuse. It was again reauthorized this year with added restrictions on gun ownership for convicted domestic abusers. Over the years, lawmakers have made a rewarding business out of the Act’s reauthorizations, looking toward inclusion and expanded protections. But this foresight only goes so far.

The 1994 version of the Violence Against Women Act introduced the first mandatory and pro-arrest policies for domestic violence incidents, encouraging states to adopt them in exchange for funding. Many took the bait. Today, 22 states and the District of Columbia maintain policies that require the arrest of at least one person in response to a domestic violence call. An additional six states have preferred arrest policies, which highly encourage immediate arrests of offenders. Both forms of policy rely on probable cause as warrant for the arrest. This might include visible marks of physical violence or possession of a weapon but the exact definition is up to the discretion of the reporting officers. Bruises and scrapes or nearby weapons, however, don’t always tell a complete story, forcing officers to quickly interpret complex scenes of violence. As of late, such discretionary tactics have come under fire as one example of the insufficient role of criminal justice efforts in lowering rates of domestic violence. This is especially true when victims belong to a community that has been historically at-odds with law enforcement.

Kase, as a university administrator, was able to file a Title IX case against her ex-fiancé, who was an MA candidate at the university at the time of the abuse. Both university and city police conducted several interviews. Describing the process with each department, she noted a disparity in attitude towards her case. University police were more mindful of Kase’s comfort and provided her with necessary reassurance. City police did not. “I felt very awkward and isolated,” she said. “I didn’t feel like they were trying to be supportive.”

This feeling is common among survivors, regardless of their sexual orientation. A 2015 survey conducted by the National Domestic Violence Hotline questioned 637 women who have experienced partner abuse about law enforcement responses. More than half of them believed that calling the police would make the situation worse and two-thirds feared that the police would either not believe them or end up doing nothing. Out of 1.3 million total nonfatal domestic violence victimizations recorded by the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, only 56% were reported to the police. Reasons for not reporting to law enforcement vary, but most follow a similar pattern: fear of the unknown. Adding police to an already heated altercation can either dampen the flame or raise it to a violent blaze. Throw in a mandatory or preferred arrest policy, where officer discretion is an active ingredient, and the conflagration can intensify.

The uncertainty can be too great a risk for some LGBT victims. Police bias or lack of training can aggravate a domestic violence incident that involves LGBT-identifying individuals. A 2002 study of police attitudes towards the LGBT community found that 25% of officers surveyed admitted to having engaged in discriminatory behavior at least once. These behaviors might include excessive force or the use of slurs like those of a 2011 incident, reported by the Williams Institute, which landed two men in the hospital. After responding to a domestic disturbance call at a Philadelphia man’s home, police reportedly beat his partner while yelling “Shut up, faggot.” More recent surveys suggest that the bias persists, even as national acceptance of the LGBT community grows. In 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union questioned some 900 attorneys, advocates and others who observe domestic violence cases on a daily basis about police response. In this group of observers, 58% reported bias against LGBT-identified individuals. Nevertheless, programs to assuage widespread discrimination are largely ignored. Tesch’s 2010 study revealed that 90% of surveyed officers had at some point responded to a same-sex domestic violence call but 81% of the same group reported having no departmental procedures in place for such calls. Fifty-three percent claimed never to have received departmental training on any LGBT-related issues.

Training programs could be the difference between faulty improvisation and successful intervention. “Police come to the scene of a domestic violence call and they don’t know what to do with the people that are involved because they don’t expect them to look the way they do,” said Verrengia of the New York City Anti-Violence Project. Proper police protocols would diminish the value of assumptions on the part of officers at the scene of a crime, but recent events suggest that is not always the case. A suspect’s appearance, age, or gender carry with them plenty of room for assumption. Atypical scenarios—the ones that training often excludes—broaden that space even further.

If both parties have been injured in a domestic violence incident, who does an officer arrest? What happens if both have weapons? What if they implicate one another, catching officers in a roundabout of accusations? What if the scene of the incident is messy, strewn with disjointed evidence? Or what if it is entirely clean, wiped of any proof? The complexities of intimate partner violence make for complex crime scenes and difficult investigations. In states with mandatory or preferred arrest policies, the pressure mounts. With the requirement or expectation of arrest, it’s easy to imagine how officers might expand their evidentiary scope in these instances. To assign blame, some officers may resort to stereotypes—consciously or not—about a person’s physical strength or “manliness” as evidence of whom to arrest. Christina Sammons is a lawyer based in Los Angeles who specializes in child welfare law and has published on the subject. In a later conversation, she said that it is common for arresting officers to see the men as aggressors and women as victims. “That’s obviously not always true,” she said, “but that’s what most people believe happens. Men are seen as usually bigger and women are thought to not defend themselves as well.”

If the line between perpetrator and victim isn’t clear, police have the option of a dual arrest, meaning they can apprehend both partners for probable cause. A 2007 study funded by the US Department of Justice, confirmed that states with mandatory and preferred arrest policies see significantly higher rates of dual arrests. The line seems to be even blurrier for same-sex couples. The same 2007 study, which involved police departments across 19 states, found that dual arrests were 30 times more likely in incidents involving same-sex couples than in cases where the primary aggressor was male and ten times more like when the primary aggressor was female.

“For same-sex couples, there aren’t stereotypes to rely on,” said Sammons. This may explain the higher rates of dual arrests, especially in cases where probable cause is easier to establish. For instance, a victim might injure a perpetrator or pick up a weapon in an act of self-defense. Such tell-tale signs of perpetration can confuse the story. Personal accounts in which the perpetrator accuses the victim can be just as baffling. Resulting confusion frequently ends in the arrest of victims alongside their abusers. A 2015 report by the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that of 850 survivors of intimate partner violence who interacted with law enforcement, 35% were themselves arrested. Aside from a slew of emotional effects, this error can burden victims with hefty legal bills and a lasting criminal record.

Just as a hostile reception from authorities can send a victim into a state of protective silence, well-trained hands can promote healing. In Kase’s experience, the warm response she received from campus police and the university’s Title IX office pulled her out of quiet refuge. “Initially, I was very hesitant,” she said about pursuing a Title IX suit. “But they made sure that I felt supported.” She experienced no pressure, no accusations, and no apparent bias.

![]()

In the most responsive educational settings today, preventing violence before it occurs is the preeminent goal. Youth programs are only one of several possible approaches but they have so far yielded promising results. A 2017 CDC report surveyed a select group of successful programs, policies, and practices aimed at intimate partner violence prevention. Among them is Safe Dates, a school-based program on healthy dating behaviors developed for 8th and 9th graders. Four years after the program, perpetration rates decreased by 56% and victimization rates decreased by 93% among student participants as compared with non-participating students.

Safe Dates demonstrates the potential of youth intervention amid staggering rates of teen dating violence, which the CDC defines along the same lines as intimate partner violence. In a 2015 study, the center found that dating violence affects millions of teenagers each year. Among them, girls have the statistically harder time: nearly one in 11 girls had experienced physical dating violence in the previous 12 months over against one in 15 boys.

The report, however, excludes any mention of sexual orientation or gender identification. Looking into it more deeply, it emerges that the rates of teenage victimization in the LGBT community reflect those of their elders. An Urban Institute study in 2014 assessed the dating behaviors of over 5,000 teens at 10 US schools. It found that a much higher percentage of LGBT-identified students had experienced some form of dating violence than their non-LGBT peers had. Transgender youth reported some of the highest victimization rates.

Explanations for this discrepancy run parallel to those for adults. True, the pressure points are similar across age groups but the burden of adolescence adds a certain tenderness. Teenagers, in fact, regardless of sexual orientation, have the highest rates of intimate partner violence across any age group. The reasons for this might seem obvious. Adolescence is a period of volatility. Shifting hormones can, for some, bring about unexplainable spurts of enmity or aggression. Coupled with the common characteristics of teendom like low self-esteem, anxiety, or a lack of dating experience there are plenty of other triggers for abusive behaviors. For sexual and gender minority teenagers, the grounds are uneven, skewed by the many stressors unique to the LGBT community. Those who are not yet public about their sexual orientation or gender identity might experience increased anxiety from fear of being outed. Those who are public, may suffer elevated stress at the hands of violent homophobia from classmates and others. Familial disapproval or concern over the possibility of disownment pose additional negative effects. While these particular stressors are risks in and of themselves, LGBT teens have been found to engage in added risk behaviors—like alcohol and drug use or sexual activity—at higher rates than teens who identify as heterosexual.

The violence endured by Madeira, Kase, and Rohlin began during their teenage years. For Madeira, partnership in any form was new to her at the start of her college romance. A streamlike “no no no” flooded from her lips when asked about the health curriculum at her high school. “I had like, ‘when mom and dad love each other very much, God magically gives you a baby,’” she said. “That was it.” The content of her Catholic high school’s health class was almost as restrictive as the lectures she received from her deeply religious parents. Like most teenagers, she nevertheless tested the waters. After a couple of secret flings with girls, she began publicly dating the boy whom she would later break up with for college independence. The only mention of her sexuality or LGBT relationships in general, however, occurred in conversations with a few close friends. The topic remained unspoken in school and at home. “It wasn’t a ‘no-no’ because people had done it before and others had bullied them. It was a ‘no-no’ because it was literally never talked about,” she said. “Our school never said things like, ‘You can’t bring a female date to prom,’ but you weren’t allowed to go to prom unless you had a date that was a guy.” She said it wasn’t even possible to attend the dance alone.

Rohlin’s high school experience was similar when it came to LGBT matters. His health classes offered no relevant material. As a member of the school’s Gay-Straight Alliance, he helped start a campaign to include such materials into the school’s curriculum, but the process was laborious. It required him to confront each teacher, one by one, about the additional material. “We even wrote petitions and sent letters to state representatives and city council members,” he said. “It really didn’t get anywhere.”

The push for educational programs on intimate partner violence in general is more common across the country than in previous decades. Today, at least 23 states have laws that allow for, suggest, or require curricula that address the topic. The only exception appears to be LGBT-specific content. The Human Rights Campaign 2014 State Equality Index found that only four states and the District of Columbia require sex education that is inclusive of LGBT youth. Eight states explicitly restrict the teaching of LGBT-related material—some, such as Alabama, going so far to require teachers to emphasize that homosexuality is not a socially acceptable lifestyle and is considered illegal under state laws. This exclusion is felt even in research to determine the best methods for prevention of intimate partner violence, much like that of the CDC’s. Dr. Messinger said there are no studies to date that “include even a module or component of LGBT intimate partner violence. Even if there are programs out there, they haven’t been evaluated yet so we don’t know if they’re working.”

Among the programs out there is Futures Without Violence, a non-profit organization dedicated to ending domestic violence and sexual assault. In collaboration with numerous outside groups, it has recently developed a program dedicated to LGBTQ and gender non-conforming intimate partner violence. Program materials are unique in that they address several form of violence unique to the community like the threat of outing or restricting access to hormones. They also provide information on hotlines and care centers that serve LGBT survivors. Still, evaluation of the program’s effectiveness hangs on a widespread adoption of the program that has yet to come.

Despite its collaborative model, the program dwarfs in comparison to the countless national endeavors to end intimate partner violence more generally, which too often disregard the LGBT community. The scale might reflect the modest size of the community but its innovation mirrors a persistent partnership. “The small size of the LGBT community can also be its strength,” Messinger said. “There’s power in the unity of wanting to protect one another’s basic human rights and dignity.”

![]()