Hilton Head’s Bad Sting

Jellyfish invaded beaches. Now what?

by Taylor Nicole Rogers

Jellyfish infestations are posing an existential threat to South Carolina’s economy.

Summers on Hilton Head Island feel hotter than they did two decades ago. The hurricanes are more harrowing, fewer loggerhead turtles crawl along the beachfront, and the shrimpers return to shore with smaller, less sellable catches. Yet no impact of climate change has been more off-putting to those who vacation on this sleepy South Carolina island than the scourge of 2018 — hoards of jellyfish, just like the merciless invaders of more touristy destinations from Texas to Australia over the past couple of years.

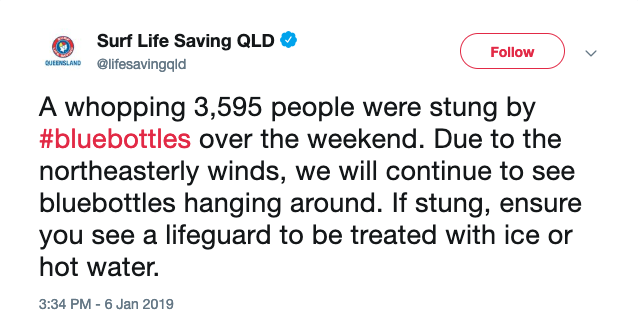

Jellyfish stung some 2,300 people along the 10 miles of beaches on Hilton Head in the first week of July 2018, the local NBC affiliate reported. Nikki Bowie, the safety program manager of the Charleston County Parks and Recreation Commission put the number of stings in the second week of August at more than 700, the Post and Courier reported. At one of those beaches, Isle of Palms County Park, the sting count was 326 for a single day, up from a mere 29 stings throughout the entire summer of 2017. The danger was so severe that the National Weather Service, in the warning statements it issued to swimmers, called the scourge a “biological hazard,” in a copy of the directive provided to me via email.

As Hilton Head prepares for its population to balloon to four times its off-season size when tourists return, local businesses and officials show no sign of having addressed or even acknowledged the growing new jellyfish threat. Conversations with scores of tourists, business owners and public officials and a review of hundreds of pages of documents from various regulatory agencies in the state of South Carolina indicate a lack of any discernible action to stem this unwelcome tide. There are no plans underway for more prominent and specific signage to warn beachgoers of the potential danger, no information online to let them know which areas are safest for swimming, and nothing more than the usual salt-water-and-vinegar spray at the lifeguard stands to ease the pain that feels like a raging fire. Yet tourism and seafood are the Island’s biggest sources of revenue, according to the South Carolina Department of Employment and Workforce. Another jellyfish infestation could damage both.

Marine biologists agree that jellyfish in these proportions signal something wrong underseas. The planet’s oceans work like a vegetable garden, jellyfish expert Dr. Lisa Gershwin explained in a 2014 Ted Talk. When the garden is healthy, it produces an abundance of tomatoes, carrots, peppers, flowers and herbs. But if the plants become diseased or if their caregivers try to reap too great a harvest, the garden devolves into a what Gershwin called a “weed-eat-weed world.” One intrusive weed chokes the vegetables’ roots, only for a more aggressive weed to engulf it later. Since the eve of the industrial revolution, human beings not only failed to tend to the needs of aquatic ecosystems but worked to extract as many resources from them as possible, thrusting the oceans out of homeostasis and into the same chaotic state as an abandoned vegetable patch.

Farmers allowed water laced with fertilizer to run off their fields and into the ocean, reducing the oxygen content of the water itself. Miners built offshore rigs to access underwater oil deposits, destroying the underwater plants that some fish depend on. At the same time, these conditions provided jellyfish with an ideal surface for reproduction. Fishermen and -women caught enough tuna and salmon to endanger two of the jellyfish’s few natural predators. Sailors brought water full of microorganisms from one ocean to another to cool the engines of their ships, unknowingly infecting and wiping out entire schools of fish that should have competed with jellyfish for food.

By all accounts, jellyfish are the ocean’s winning weed. Despite their simplicity, or perhaps because of it, they are the ocean’s best survivalists. They can clone themselves in 13 different ways, go long stretches of time without food and thrive in a range of water temperatures and salinity levels that other sea creatures cannot.

![]()

Other beachfront towns in the same position have taken a far more proactive approach to the jellyfish problem than Hilton Head, confronting the menace with action instead of secrecy. In Antibes, France, a catamaran nicknamed the “jellyfish hoover” sucks jellyfish out the waters near its beaches while another beach built nets to keep them out of swimming areas. Barcelona collaborated with local researchers to find a way to educate the public. The state of Queensland in Australia closed its beaches for entire days at a time to protect swimmers.

Research in other communities has shown that warning the public with signage and alerts on social media would be a good way to start. On the beaches of Catalonia in Spain, big businesses that control the tourism industry pour large sums of money into addressing their jellyfish problem. A 2015 study in the research journal Ecosystem Services reported that after jellyfish stung 21,000 Catalonian beachgoers in the summer of 2006, Spain joined Italy, Malta and Tunisia in a 2.6 million Euro European Union-funded program called ‘Jellyrisk’ to exterminate the Mediterranean’s gelatinous pests. The next year, the Spanish Environmental Ministry organized a network of commercial fishermen, recreational boaters, spotter planes and satellites to keep track of where clumps of jellyfish, collectively called a bloom, were massing. The government retrofitted boats and sent them out to clear litter from the ocean and suck jellyfish out before they could enter swimming areas. The local government in Murcia spends the equivalent of $560,000 annually to build 60 “jellyfish-free” swimming zones guarded by underwater nets. However in 2008, after a year of experimentation with the method plus millions of euros and thousands of man-hours, Spanish Environmental Minister Cristina Narbona admitted that the plan had failed to eradicate the problem.

Jellyfish nets protect swimmers in Murica, Spain

In 2012, a group of researchers led by Macarena Marambio Campo at Barcelona’s Institute of Marine Science tried a simpler and cheaper solution with the support of Jellyrisk. Unlike taking jellyfish out of the ocean or installing nets to separate them from swimmers, it’s a model that could be exported to smaller communities with tighter budgets, like Hilton Head Island. Campo worked with the municipal governments in the Barcelona area to design an app known as MedJelly, that gives beachgoers up-to-the-minute information about which beaches had jellyfish and what to do if when stung, in addition to daily warnings about rip currents, strong winds and the UV radiation index. When users tap on the app’s blue icon, they see a map of all the beaches on the Catalan coast, each marked with a red, yellow or green pin indicating the level of danger.

Before the app got off the ground, Barcelona’s bureaucrats were hesitant to work with Campo, afraid that publicizing jellyfish data would scare away tourists. Campo argued that empowering beachgoers to check for jellyfish, just as they check for the weather, would be a benefit to tourism, not a hindrance. Knowing where the jellyfish are each day, she said, enables visitors to plan beach trips with foreknowledge, just the way one would take an umbrella if a thunderstorm was anticipated. “You don’t avoid going to the mountains because of mosquitoes,” Campo said, Hikers would simply bring along bug spray. Beachgoing, she said, doesn’t have to be any different.

The success of the app, Campo said, has proved her point. When it was first introduced during peak jellyfish season from July to September of 2012, tourists downloaded it more than 7,000 times, making it the most downloaded app in the country that summer. The next year, it was upgraded to cover all 230 beaches in the Catalonia region. Camp said it minimized the sales slumps restaurants and beachfront vendors previously suffered on the days the jellyfish were at their worst.

The success of MedJelly inspired one of Campo’s colleagues to conduct a study to quantify the economic cost of a jellyfish bloom. In June of 2013, before the jellyfish set in, and again in July when they had taken over, Paulo A.L.D. Nunes, a Jellyfish researcher, joined by students from the University of Haifa in Israel to poll beachgoers at a popular beach in Tel Aviv with some of the world’s most dramatic jellyfish blooms. When the jellyfish are at their worst, respondents cut their beach trips by between 3% and 10.5%, resulting in a loss of somewhere between $2.1 million and $7.1 million of tourism revenue.

![]()

The study found that many beachgoers who got stung avoided the sea for the rest of the season, but no group was more hesitant to return than those who did not know there were jellyfish in the area and got caught by surprise. That is the situation Jessica Grant found herself in after a jellyfish caught her off guard on Seabrook Island in South Carolina. Every August, Grant’s family makes a weeklong pilgrimage to the small beach town outside Charleston. More the type to swim than sunbathe, Grant had spent hundreds of hours swimming in the area over the years. Naturally, when she waded into the warm Prussian blue waves this past summer, it never occurred to her that the swim would bring her close to death.

Last year, the trip to the private beach resort of Seabrook Island held extra significance for Grant, who is 23, as these were supposed to be her last lazy days before beginning a masters degree program at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell. But as she and her dad splashed around—her sister Jasmine watched on from the sand—a prickling sensation in Grant’s calves gave way to excruciating pain in her right arm. “It literally felt like I got electrocuted,” Grant said. She began to scream and hyperventilate as her father and sister coaxed her onto dry land. The pain spread further, sending cramps throughout her body.

When she finally laid down on the sand—she didn’t remember how she got there but was later told her dad helped her— Jasmine unwrapped a thin tentacle from the crook of her sister’s arm. Once Jasmine finished, Jessica limped up the beach to the Seabrook Island Beach Club, where her family had weeklong passes to eat and sunbathe seaside between dips in the ocean.

This sign welcomes beachgoers to the Hilton Head’s beaches.

Jessica had seen a small sign at the Beach Club warning swimmers to beware of jellyfish on one section of the beach. Not only was the bulletpoint presented without emphasis but it did not even say where that section was. Most importantly to Grant, it did not mention that the jellyfish were actually Portuguese Man o’ War, a marine hydrozoan often considered a part of the broader category of jellyfish. It has a potentially lethal sting that is especially dangerous for small children. Yet untold numbers of visitors like Grant stepped onto the beach completely ignorant of what awaited them in the surf.

Grant took this photo of her jellyfish sting the next day.

When Grant made it back to the Beach Club, she waved down the first staff member she saw for assistance. Another Club employee helped remove some of the lingering stingers from her wounds and sprayed her welts with the vinegar-seawater remedy to reduce irritation. Nonchalantly, he identified the species of her attacker by name. That made her think that only visitors like herself did not know about the invasion of poisonous jellyfish, a feeling that was affirmed by the dozen other tourists who called out to her as they walked past to say that the jellyfish had also taken them by surprise. The Seabrook Island Beach Club did not return requests for comment.

The Club is just one of countless small hospitality businesses in the Carolina Lowcountry that stand to loose if the region doesn’t address the worsening jellyfish problem. The general inaction on the part of the municipalities has led to a general reluctance from local authorities and business owners to owe up to the situation.

The current model of lifeguarding in the Lowcountry confounds attempts to do a better job of warning beachgoers of the threat. South Carolina has no uniform method of warning beachgoers of the presence of dangerous marine life. Although most of the state’s beaches are open to the public, many communities rely on private contractors to provide lifeguards. The net effect is that many lifeguards have to divide their attention between saving lives and turning a profit. Shore Beach Services, the company that manages Hilton Head’s lifeguards, even awards bonuses to guards who bring in the most revenue from renting umbrellas and beach chairs. The side business supports the lifeguard service, but it also leaves swimmers to fend for themselves for as much as a half an hour at a time. As small businesses themselves, these beach services have to decide how much to tell swimmers about potential dangers when they know doing so might scare away business.

Why was the system designed this way? “It’s because of budgetary constraints,” said Joe Cronin, the administrator of Seabrook Island, the private resort town where Jessica was stung. Seabrook Island’s lifeguards have to spread their time even thinner than their counterparts at Hilton Head. The Seabrook lifeguards patrol by driving up and down the beach on four-wheelers instead of watching from highchair. “If you take out one-time road repair projects,” Cronin said, “our town budget is barely over $1 million.”

Robert Edgerton is the director of Barrier Island Rescue, the lifeguard service that serves the municipalities surrounding Charleston. He said that a further block is the requirement that local officials must first approve any public warnings lifeguards might want to share with the public. “Most of these communities are many beach communities are focused on tourism,” Edgerton said, “and so any message that we send about dangerous sea creatures and stuff has to be vetted through them to really make sure that we’re doing the right thing and sending the right message.”

A lifeguard from Lack’s Beach Service sets up chairs and umbrellas to rent to patrons.

Weslyn Lack-Chickering is a lifeguard and operations manager for Lack’s Beach Service, another lifeguard company that contracts with the City of Myrtle Beach to provide lifeguard services along 60 miles of coastline. Lack’s also rents umbrellas and chairs for $40 a day to help cover the cost of recruiting and training some 130 lifeguards each summer, most of whom are college students from out of town. Although Hilton Head has only recently experienced the phenomenon, Myrtle Beach, less than an hour’s drive away, and a few other South Carolina coastal destinations have sometimes had a jellyfish influx for a few weeks in August, but never the extremely dangerous ones. Lack-Chickering, who has worked the beaches for the past decade, said the summer of 2018, she said, was simply “different” across the Carolina Lowcountry. The jellyfish arrived in June, 2 months earlier than expected and stayed all summer. They seemed to be everywhere, she said. On top of that, she said the water’s deep green color makes it impossible for lifeguards to detect when something is lurking below the surface. The only warning the lifeguards get is the screams of the stung.

When the jellyfish get particularly bad on one part of the beach, Lack-Chickering’s lifeguards order swimmers to exit the water for 15 minutes in hopes that the current will move the jellyfish along. During the worst parts of last summer, the temporary closures occurred up to 10 times a day, triggering a mass exodus of families to their hotel pools. Lack-Chickering said it decimated revenue for the company in chair, umbrella and kayak rental. To make matters worse, the devastation brought by Hurricanes Florence and Michael in September and October ended the beach season two months early. The hurricanes undeniably did more damage to the Beach Service’s bottom line than the jellyfish, but the combination has left the company on shaky financial footing going into 2019.

When asked what her plan was to recoup her company’s losses, Lack-Chickering’s answer was simple: “pray; and hit the ground running next summer. That’s the thing about Mother Nature,” she said, “friend or foe, she runs the show.”

Hilton Head’s permanent residents are all too aware of Mother Nature’s control. The island looks more like a national park than one of the country’s most popular beach towns, but that is by design. The government of the South Carolina barrier island has managed to maintain a park-like atmosphere imagined by the developer of the island’s first resort, Charles E. Fraser, in 1956. The tallest tower blocks of beachfront condos don’t rise above six stories, a third the height of the apartment towers in Myrtle Beach. Owners of beachfront homes are forced to go dark after 10 p.m. to avoid distracting young turtles making their way to the surf after hatching. Even McDonald’s couldn’t secure an exception to the town’s Land Management Ordinance, and painted the iconic golden arches out front of its Hilton Head location a subdued shade of yellow and kept them close to the ground. The restaurant is barely visible from its own parking lot behind a line of oak trees dripping with thick Spanish moss, All the buildings are faced in neutral-toned stucco or painted paneling, with a uniformity that helps them fade into nature.

“That’s the thing about Mother Nature.

Friend or foe, she runs the show.”

When the construction of a new bridge from the mainland opened the Island to large scale tourism, the New York Times predicted that although “many people should come here to make their summer or full-time homes on Hilton Head . . . it is not likely that the island will be greatly changed by them.” The Island has changed, however, but many of the differences are not readily visible.

![]()

Mel Bell is the director of fisheries management for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. In a telephone interview, he said that the stinging jellyfish that tourists have started to encounter on the beach are nothing compared to the hoards of another species of jellyfish that can be seen from an offshore fishing boat. That morning, Bell was in the process of preparing for a seminar on new techniques for regulating local commercial fishing.

Traditionally, which state organizations manage which fisheries is broken down geographically. Because white shrimp, the kind one would enjoy in shrimp cocktail, are most often found in South Carolina, Bell’s office is responsible for ensuring how many of them are caught and when. But as ocean temperatures rise, the shrimp have followed the warm water up to North Carolina. How to manage shrimp that cross state lines is only the newest result of warming water temperatures that Bell’s office has to address.

It was a 35-year-old problem that Bell and I discussed — cannonball jellyfish, or as the shrimpers call them, jellyballs. Bell first began paying attention to the jellyballs while working on a project to help recreational fishermen catch Atlantic state fish. Fishermen would catch jellyballs and then use the tough outer layer of the jellyballs—Bell compared it to a watermelon rind—as bait.

That was the pest’s only known helpful attribute. Most of the time they just get in the way. Because the jellyfish tend to stick together, a fishing boat’s net can catch several thousand pounds of them before anyone on board knows what’s happened. Their sheer weight has been known to sink fishing boats in Japan.

In 2014, a New York-based business thought it had found a way to help struggling shrimpers while making a nice profit. St. Helena Island is a sea island even smaller than Hilton Head and located on the other side of Hilton Head-Bluffton-Beaufort metropolitan area. For a brief period in 2014, it was the home of a jellyball processing plant where the jelly balls would be dehydrated in preparation for export to Asia.

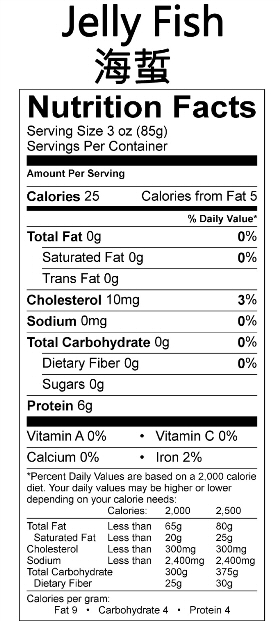

Golden Island International, a jellyfish processing plant in Darien, GA, analyzed the nutritional benefits of eating jellyfish.

A meeting of the Beaufort County’s Natural Resources Committee in October of that year was just one of many times tensions over the jellyfish plant boiled over. “That smell has defined the industry and the towns that they operate in,” said John Cashen. He was at the meeting to represent the Jellyball Assessment Group, a coalition of local residents who organized to oppose the plant. His reference was actually to Darien, Georgia, home to a jellyball processing plant called Golden Island International, which opens in February each year and operates seven days week with no plan to slow down until June. The company has been in operation since 2002.

Bell acknowledged that the industry is “a little on the odorous side.” Even Wynn Gale, a fisherman who supplements his income by catching jellyfish during shrimp’s offseason, said the scent is “undescribable” and lingers over downtown Darien. In fact, the smell is so strong that in April 2015, organizers of Darien’s annual “Blessing of the Fleet” festival pleaded with the plant’s management to cease operations for a few days before and during the three-day event, which the firm agreed to do. Since that time, the plant has since relocated to a less populated part of Darien.

Georgia’s jellyball industry is the result of a fishing accident. Commercial shrimp boats use a method called trawling to catch shrimp. “Shrimpers,” as the fishermen are known in the Carolina Lowcountry, drop large weighted trawl nets onto the ocean floor to sweep up everything in their path including blooms of jellyfish.

The problem got so bad that one Darien-based shrimper, Sinkey Boone, developed a device for trawl nets that would allow the jellyballs to escape while keeping the coveted shrimp inside. Though the device didn’t work as originally planned, it had the unintended advantage of saving sea turtles and is now mandatory for all shrimp boats in the United States.

Nonetheless, the shrimpers kept catching jellyballs. Eventually, they realized that they might not have to just dump them back into the ocean. In Asia, jellyballs turned out to be in high demand as a popular topping for Thai and Chinese salads.

“What lined up is a demand for the product in the Asian market and the availability of the animal off of Georgia,” Bell said, “and some innovative shrimpers that figured out how they could basically trawl specifically for jellyballs.”

Bryan Fluech of the UGA Sea and Marine Grant said jellyballs have now become Georgia’s largest fishery by volume. For Wynn Gale, jellyballing was a way to breathe new life into a family business that had long been on life support. For the past several years, Gale has added $30,000 to his annual income by jellyballing after shrimping season ends. “It’s all anyone can talk about,” Gale said, “the smell or the money.”

Wynn Gale describes his experience as a Jellyballer.

Georgia jellyballers have one important advantage over their Lowcountry counterparts — time. Both the South Carolina and Georgia governments decide what species can be caught in their waters based on the lifecycles of each species when they’re in the area. Georgia’s shrimping season typically ends at the end of the calendar year, as the shrimp follow cool currents north. When the jellyfish start blooming in early spring, Georgia’s harbors are full of idle shrimp boats that aren’t making their owners any money. Meanwhile, shrimpers based in South Carolina capitalize on the end of shrimping season, which won’t officially wrap up until a month later. For boats based in South Carolina, jellyballing would mean turning their backs on shrimping, the more lucrative fishery. As Bell said, “It wasn’t the sort of filling in the gap opportunity for us as it was for Georgia.”

The timing problem made it unlikely that shrimpers in Beaufort County could replicate Gale’s success. This became a common rebuttal to the county’s jellyballing advocates. Ultimately, scheduling conflicts with the shrimping season paled in comparison to the other rhetorical weapons launched against the new business, first called Carolina Jelly Balls, LLC. and later renamed Nautica & Co., Inc, in the legal war that ensued. Meetings of the Beaufort County Council became the battleground.

Carolina Jelly Balls set up shop in Beaufort’s Commercial Fishing Village Overlay District, a piece of land that has been used almost exclusively by the seafood industry going back to the County’s roots as a small fishing village. It was designed to help slow the decline of the seafood industry, according to a report on aquaculture policy development by the Virginia Coastal Zone Management Program. Zoning laws allow seafood businesses to operate within the district’s borders with minimal permits unless the business’ activities constitute a “special use.”

Cashen’s group of anti-jellyball residents were determined to see jellyballing as a special use, meaning it would require a separate permit that the county would likely deny. Cashen argued to county officials that the process of unloading and processing jellyfish is unlike any commercial activity the region had ever seen before. He harkened to the slimy, natural toxin that jellyfish emit to protect themselves when threatened, saying that any runoff water from washing the jellyfish would be contaminated, possibly jeopardizing the water quality of the local creek. He said the plant would also treat the jellyfish with alum, a common household spice used to keep cucumbers crunchy during the pickling process. That, too, could show up in the runoff, he said.

David Tedder, a local lawyer representing the plant at the hearing, denied that the plant had ever used alum while processing jellyballs and said it had no plans to. Furthermore, County Councilman Jerry Stewart noticed some holes in Cashen’s arguments. Stewart obtained a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Idaho and has held posts at the US Department of Energy’s Morgantown Energy Research Center and at the Connecticut-based engineering company, Industrial Technologies Inc. At the time of the hearing in 2014, he was District 6’s representative on the County Council. A white-haired man in his late 60s, he carefully evaluated every presentation from his seat at the boardroom’s center table.

“You could fill this room 10 times over with the number of phone calls and emails we’ve gotten on this issue.”

As evidence that the plant was making the creek toxic, someone passed around photos of the creek with an overlay of foam where the plant had been releasing its runoff. Stewart pointed out that they had no way of knowing where the foam had come from or what it was made of. He also said that he thought it was odd that everyone was so adamant about naming the jellyballing industry as the culprit when other businesses in the commercial fishing village surely had some responsibility for the pollution.

“I’m not sure that a lot of this isn’t emotional, that it’s truly rational and scientific in its basis,” Stewart said at the time, adding that without the Department of Health and Environmental Control coming forward, “I don’t see much of an alternative for us, but it’s very disturbing to me.”

Then US Rep. Mark Sanford told The Beaufort Gazette that the issue had generated more noise than than any other at this end of his congressional district. “You could fill this room 10 times over with the number of phone calls and emails we’ve gotten on this issue,” he said. In the end, the proposal from Cashen’s group passed the County Council. But before the changes could come into effect, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control shut the plant down anyway for additional toxicity testing.

Despite the result in Beaufort, Bell said future jellyballing ventures in South Carolina are not out of the question. “They’ve obviously worked through it somehow down in Georgia,” Bell said. “I think a lot of the pushback we saw down in our southern county, Beaufort County, some of it was perceptions from how things played out in Georgia in the early years. And they didn’t want that in their towns.”

Jellyballers reel in their catch off the coast of Darien, GA.

A catch of jellyfish doesn’t stay fresh for long so a nearby processing plant is essential. And because jellyballers catch such huge quantities, shipping them long distance woudl be cost-prohibitive, Bell said. Although 95 percent of their weight is water according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, it is only removed during processing and not counted in the weight that buyers pay for. So having the removal process happen at source is essential.

Though Bell thinks the chances of resurrecting the processing plant are slim in 2019, residents haven’t forgot about it. Some of them, like my kayaking instructor, wish the Beaufort plant had stuck around so tourists wouldn’t see so many jellyfish in the water.

![]()

Dr. Jennifer Purcell was reached over Skype from Brazil, where she has been studying tropical jellyfish for the past year. In fact, her entire career has been devoted to the “rodents of the sea,” as she calls them, a pursuit inspired by her first encounter with jellyfish as a four-year-old. Even if Carolina Low Country decided on a way to address the problem locally, she said, its scale is global. Americans, she said, are in denial about the world’s jellyfish problem. Because so few accept that the climate is changing as a result of human action (23% according to 2018 survey conducted by Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication), they don’t tend to take action as readily as their counterparts overseas.

At the end of my conversation with Dr. Purcell, I asked which of the potential solutions we discussed could mitigate the world’s jellyfish problem. “Oh honey,” she said, “it’s already too late.”

![]()