Welcome to the Hell Hole

Where poverty meets mental illness

by Anne Cruz

She is a 21-year-old community college student in graphic design who has suffered from anxiety and depression since she was eight years old. She lives in a modest frame house in Paterson, New Jersey, with her parents and her brother, who has cerebral palsy. Stephanie, who asked to be identified only by her first name, does what she can to address her symptoms. From internet forums, for instance, she has learned to stave off the onset of panic attacks by taking three long breaths to keep her from hyperventilating.

Professional help, she said, has never been an option, not even after she was hospitalized overnight at age 13 because a classmate overheard her contemplating suicide.

In Stephanie’s family, other financial burdens have kept her mental health from being a priority. Her father works as an auto technician; her mother stays at home to tend to her younger brother’s needs, feeding him every four hours and administering his medication several times a day.

Beyond the breathing technique, Stephanie’s art is her main coping mechanism. When she draws or paints, she said, she’s able to “let everything go.” It also gives her a way to earn money from freelance art commissions to help pay for her college classes two days a week. Her parents help cover the rest of her costs, which range from $300 to $1,000 per class.

The teenaged hospitalization episode could have been the turning point for her to begin professional mental health care. Doctors at the time identified her symptoms. They made a preliminary diagnosis and urged her parents to follow up by seeking professional help for her. They even threatened to report the family to Child Protective Services if they did not. Her parents agreed but only to secure her release from the hospital. “It was out of the question,” Stephanie said. “We couldn’t afford it.”

Not even a sliding scale payment scheme would have made consistent treatment for Stephanie possible. Given the invisibility of her illness, it was hard for her family to understand its urgency. She said that not only would her family struggle with the financial burden of treatment, but their own cultural beliefs saw mental illness as weakness rather than as a medical condition. This attitude is not uncommon in their Latino community in Paterson, which has an average annual income of $32,915.

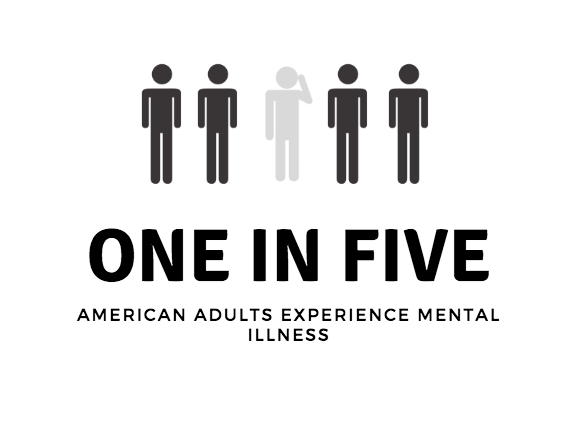

Stephanie’s situation puts her among the 20 percent of American adults who experience mental illness, and also among those without the resources to confront the difficulties their condition presents. As hard as mental illness can be for anyone to face, poverty dramatically exacerbates its impact on the individual.

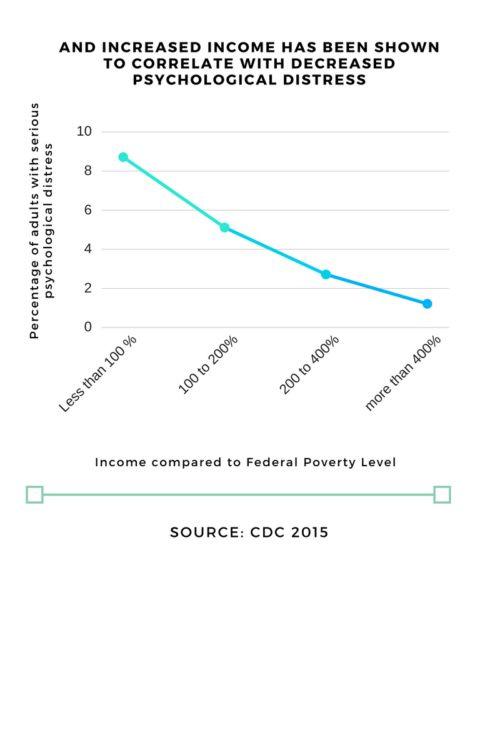

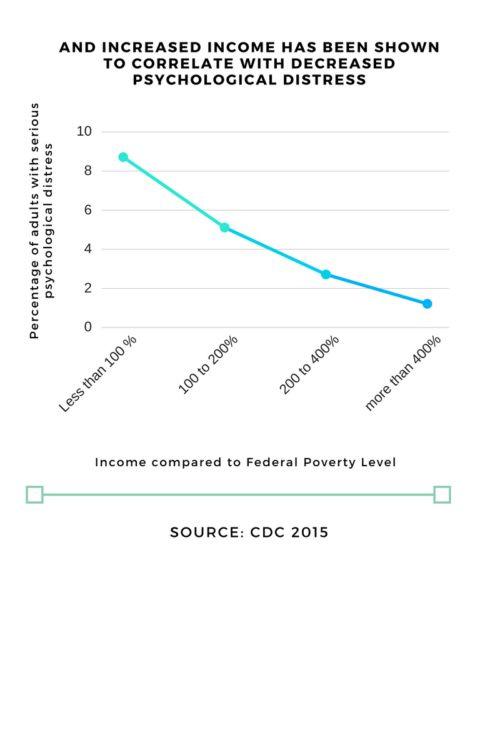

A 2015 study by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that among US adults, a decrease in income level correlated with an increase in serious psychological distress. Individuals may be able to find emergency short-term help at no cost, but sustained reliable treatment is rarely possible for the economically disadvantaged. The barriers are not always seen: from the cost of medication to the cultural stigmas that discourage therapy and prevent individuals like Stephanie from seeking professional care. Others are afraid of the discrimination that may result from their diagnoses. As a result, the poor who suffer from mental illness must make do with limited resources, worsening both their health and their financial insecurity.

Cost is the most obvious impediment to treatment. It is sometimes a trigger for anxiety itself. For Carrie, a 33-year-old living in Minnesota, her fear of being denied coverage for her mental illness prevented her from seeking treatment for more than 10 years.

Carrie’s paternal family had a history of bipolar disorder, and her mother’s family is “full of depressives,” many of whose lives ended in suicide. On particularly rough days, Carrie said she feels as if she is doomed to repeat the fate of her grandparents and several other relatives, who died after their untreated mental illnesses made them reclusive hoarders.

“I remember how my aunt died, and trying to clean out her house by literally wading through waist-high garbage,” Carrie said, calling the experience one of the most horrible days in her life. “So there’s a sense of, ‘Is there a script? Is there nothing I can do to not follow?’ Will I end up like my grandfather and my grandmother, who let themselves die from neglect?”

Carrie, who grew up in Maryland, had experienced bipolar disorder’s telltale swings of depression and mania since she was in high school, but didn’t seek treatment at that time. Her mother worked as a school administrator and her father was frequently in and out of work due to his own mental health. Carrie’s parents did not see mental illness as the reason for the behavior patterns in the family and that discouraged her from seeking help.

In college, Carrie’s depressive to manic mood swings had her alternating between acing and failing her courses until she dropped out of school. At 21, a stranger entered Carrie’s home and sexually assaulted her. That prompted the State of Maryland to pay for her therapy and counseling, during which the therapist suggested a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Carrie asked the therapist not to include a diagnosis in his notes — she was uninsured and knew that bipolar disorder would be considered a pre-existing condition that would complicate her ability to obtain health insurance in the future.

“I said, ‘You cannot write that down,’” Carrie remembered, and he understood. “I could not afford the medication and if I had that on my record, it’s possible I would never get health insurance, period.”

Before the passing of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were considered pre-existing conditions. More than 30 states allowed insurance companies to use these conditions—everything from postpartum anxiety to acne—to increase premiums or deny coverage. One study found that premiums were raised as much as 50 percent for someone with depression. Although these provisions did not specifically target people with mental illness, insurance companies often used such diagnoses to increase the cost of care before the ACA. In effect, the treatment that should have been helping those with mental illness created even more worry.

In 2005, when Carrie began therapy, she had already heard horror stories from those seeking insurance with pre-existing conditions and knew that some therapists would go so far as to change a diagnosis from, say, borderline personality disorder to bipolar disorder, so that it would seem like a new condition and thus side-step future insurance issues. “I had a friend who had that happen to her,” Carrie said. “And when she changed health insurance from job to job, her therapist had to invent new diagnoses for her each time.”

Carrie said her friend’s medication also changed with each new diagnosis, ineffectively treating her illness. The state of Maryland provided her with free counseling after she was assaulted, but when she moved to Minnesota, the coverage did not travel with her. She did not want to jump between diagnoses, and knew she could not afford $600 to $700 dollars worth of psychiatric medication each month on her own. So at that point, she opted for no treatment or medication at all.

Carrie married in 2007 and one year later, her husband got a job at IKEA, which provided both of them with health care benefits. Having insurance enabled Carrie to get an official diagnosis of bipolar II disorder and severe anxiety. Since then, Carrie receives psychiatric evaluations every few months and takes a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant during the winter months for symptoms of seasonal affective disorder, and the occasional anxiety sedative.

Even though both Carrie and her husband have found stable work, the couple still faces financial complications. Halfway through our first interview, Carrie fielded a call from a debt collection agency. “I don’t feel like taking it,” she said. While her husband’s job pays their bills and provides essential health coverage, there are not many advancement opportunities at the home store conglomerate. Still, Carrie’s husband stays with the company because the health insurance is so vital, and Carrie’s medication is too valuable to risk.

While the ACA has protected people like Carrie since 2014, efforts to repeal it create worries about maintaining treatment and medication in the foreseeable future. If repealed, Carrie could lose her coverage if her husband switches jobs, or if IKEA changes providers. Losing Obamacare could also mean increased premiums with their existing plan. These anxieties, Carrie said, pile onto the already existing symptoms of her illness.

“That’s where poverty locks you in,” Carrie said. “It tied my husband to this job until Obamacare because if he left the job, he knew that I would probably maybe last six months before I killed myself. Even though he had offers that would have been theoretically for better jobs, he couldn’t take them.”

Carrie’s stress over paying for both her medication and bills is not a singular experience, but it’s a common stressor among those struggling with mental illness and poverty.

A 2016 study by the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute found that adults with depression and problem debt (a sign of financial instability) were more than four times more likely to have depression symptoms after 18 months than those without problem debt. The institute also found that for anxiety, those with financial instability were 1.8 times more likely to still identify with the disorder 18 months later than those with dissimilar socioeconomic factors.

The same study reported that more than 80 percent of the survey’s 5,500 respondents with mental health problems said their financial situation had made their mental health problem worse. For those with depression, financial woes can worsen feelings of helplessness. For people like Carrie, who experience immense anxiety in their everyday lives, the added pressure to make ends meet foster anxious thoughts.

“Money is a huge issue, it’s very anxiety inducing.” Carrie said. “I can’t open my checking account to just look at how much money we have.”

Carrie also described how her anxiety and money concerns compound one another when dealing with the day-to-day necessities like keeping house. She said having a mental illness is like arriving at a speed bump. Those without mental illness are able to recognize obstacles and slow down accordingly, but for Carrie, her anxiety makes her view the speed bump as a road-block she cannot react to quickly enough or well enough.

“I’m frequently living in the kind of situation where you don’t let people come over because it’s too embarrassing,” she said. “Our sink has not been draining for about a year, so we have it run into a bucket which I empty into the toilet. I would rather deal with that than call a plumber and find out we can’t afford it.”

Carrie and others like her are protected by ACA for now, despite attempts to repeal it through the 2017 American Health Care Act that passed in the House of Representatives but never made it to a Senate vote. But with a president in office who campaigned on the promise to repeal ACA and Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, a future attempt to remove protections for those with pre-existing conditions is more likely than not to become law. Given the uncertain future of health policy, Carrie said she wouldn’t know what to do if faced with the choice between necessary, expensive treatments and her other financial obligations.

“With the laws being what they are, anything could happen at any moment with the government,” Carrie said. “Obamacare could leave. And then who knows what would happen?”

Less visible impediments to obtaining the care an individual needs often come from a combination of family and community norms. Stephanie, the graphic designer, for example, said her Latino family’s conservative views may not have been the primary block to her seeking help, but they did make doing so more difficult. It was hard for her to talk to her parents about what she was experiencing. “When you’re from a family that doesn’t really talk about mental illness ,“ she said, “it kind of becomes taboo.”

I asked if she had any sort of support system beyond her family — if not a therapist, perhaps a local support group of some kind. She said no. If there were organized mental health resources in Paterson, she was not aware of them. She does, however, have one friend she can confide in, who also grew up in Paterson. Aless V. is a 21-year-old film and television production student at New York University who has had ADHD since she was five years old and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder last year. The two young women sometimes share confidences and support one another.

Aless’s parents escaped severe hardship and poverty in Peru to immigrate to the United States when she was a young child. As with Stephanie, manifestations of Aless’s condition also appeared early on in life. But in Aless’s case, her family’s memories of life in South America dominated their views on mental illness. Aless felt that the difficulties she was experiencing in and out of school simply paled by comparison to what her parents had endured before they came to the United States.

“I think my parents are very empathetic people,” Aless said. “I think they understand when I’m in pain, but if I’m just saying, ‘I’m struggling with this’ or ‘This is making me anxious,’ I don’t think they have a grip on what that means.”

Not only was their lack of understanding a block, but when Aless was 10, her parents divorced, sending the family below the poverty line for a couple of years. Her mother, who was uninsured at the time, became the children’s primary source of support and even if she had been inclined to seek professional help for her daughter, she could not have afforded it. On top of that was the cultural stigma Aless said her community ascribes to mental health treatments like therapy or medication. The power of mental health stigma is well documented in its ability to dissuade those needing help from seeking it.

As Aless explained it, her family and neighbors in Paterson “associate therapy with mental clinics, which they would call loony bins. It’s such an outdated term, but even in a community that’s so heavily people of color, mostly black and Latino, words like that are what we got out of American culture. That’s one of the things that sticks.”

Aless explained that in her community, caring too much about one’s mental state is seen as an indulgence or a sign of weakness. “To care would be considered taking it too seriously,” she said, “or you’re thinking too much into it.” That wasn’t to say depression and anxiety weren’t common in the community, but that talking about it was the taboo. In Paterson, Aless said, “There’s a general culture that says, ‘Suck it up,’ the only way for you to feel better about suppressing your own pain is to tell others to do the same thing.”

Nevertheless, despite all the impediments, when the family’s financial situation stabilized years later, her parents did allow her to seek help. Aless saw a therapist, who prescribed medication that she has been taking ever since. So in her view, help “came with money,” she said. “It came with access, and, like, better security. I started going to doctors.

“There’s a difference when you don’t have money to deal with something,” she went on. “You pretend the problem doesn’t exist, and the moment you have the money to deal with it, you remember that it exists.”

Dr. Peter Guarnaccia is a medical anthropologist at Rutgers University who researches mental illness in Latino communities. He said Aless’s and Stephanie’s experiences with stigma were typical of the attitudes he has encountered in other such cases. Cultural stigmas on mental illness are not unique to Latinos, he said, but they can be a particularly strong force within these communities.

Echoing Aless, he said, “I think there is also this idea of, ‘It’s up to you to get over on your own,’ the idea that it’s almost a moral failing rather than an illness is also part of it. I think class, gender, culture all interact together to affect that.”

In a 2006 paper Guarnaccia co-authored, “‘It’s Like Going through an Earthquake’: Anthropological Perspectives on Depression among Latino Immigrants,” he particularly examined the cultural barriers to mental health care faced by immigrants. Participants in his focus groups would face and overcome financial and bureaucratic obstacles to treatment, only to be ostracized in their communities. Twelve years after the study’s publication, Guarnaccia still remembers one woman from the focus group who was finally able to seek treatment, only to have her neighbors call her “la loca,” or the crazy woman, when she returned home from therapy.

“I think the challenge is that [people think] if you’re not mentally healthy, you’re loco, or crazy, and there isn’t a lot of understanding of all the different ways of having mental health problems in between,” Guarnaccia said. “In many Latino countries, mental health services aren’t widely available. So people don’t really understand what they are. What people do know is that there are hospitals for people with serious mental issues. That’s their understanding of it.”

Aless regularly saw these misunderstandings of mental illness in her hometown when trying to find support for her anxiety and ADHD. “If you’re going to doctor, getting any help whatsoever, then you have to be crazy, you have to be certifiable,” she said, saying there wasn’t any recognition that someone could function well while dealing with their mental illness. “With older generations,” she said, “it’s worse. A lot of them being immigrants from countries with an even stronger stigma, they teach children to suppress symptoms and can’t really comprehend what these people are going through. It is out of fear more than it is out of judgment.”

Cultural views on values such as control and hardiness can cause further isolation for individuals experiencing mental illness or even self-stigmatization. Guarnaccia spoke of the work of a colleague of his, Roberto Lewis-Fernández, who has studied the importance in Latino culture of being in control. “One of the scariest ways to be ill is to be out of control,” Guarnaccia said. “ That kind of feeling is seen as very, very serious.”

Guarnaccia and Lewis-Fernández have studied ataques de nervios, a syndrome similar to panic attacks that is known to affect Caribbean Latinos. Guarnaccia said that one of the condition’s key features is the loss of emotional, physical, cognitive control. “Roberto particularly emphasized that that’s really the kind of core issue in ataques de nervios. Being mentally ill is being out of control and that scene is very scary both internally when someone feels that way, but also by the community at large.”

Ultimately, Guarnaccia thinks that addressing cultural stigmas in these groups is crucial to improving their community mental health care models. Culture, he said, can be a reason why a community might reject certain methods of treatment, like psychiatric medication, and understanding common misconceptions can help create more culturally competent care.

Citing the reactions of Latino immigrants in his focus groups, he noted another aspect of the tendency to stigmatize: “People feel like the medications are very dangerous, that they can be addictive,” Guarnaccia said. ” In their home countries, the medications that are available often are some of the older medications, at least for people who are using the public mental health system, older medications which can be more addictive than the newer medication. And they don’t realize the differences. So it’s the stigma of mental illness, but it’s also the stigma of treatment.”

Aless said that in her case, as disinclined as her parents were to putting her on medication, they still preferred pills to talk therapy. “So even with years and years of experience, they still don’t know about why my illness exists or what it is. All they can ever see is the physical aspect: my grades went up when I started taking medication, so that medication is helping. But they don’t understand there’s a condition that is the source.”

Stephanie and Aless did not go to the same public high school. Thanks to scholarships, Aless was able to attend DePaul Catholic High School, a private school in Wayne, NJ, where the median household income was three times that of families in Paterson. At DePaul, seeing therapists was commonplace among Aless’ more privileged classmates. That experience gave her access to far more information about mental health issues than had been available in her home community. It also gave her far more acceptance of her condition than was available to Stephanie or most of her other hometown peers.

“Seeing the way wealthier students were treated for their own conditions at least informed me of the impact that mental illness can have on a person regardless of their circumstances,” Aless said. She still experienced bullying and isolation in her new school, and the helpful changes in her behavior came with some undesirable side effects. Nonetheless, “Even if the social aspect of it was quite unpleasant and biased,” Aless said, “at least the teachers and staff recognized the prevalence of problems. This built up my understanding of mental illness and at least gave me a realistic take on how the world sees mental illness in a demographic other than the one I lived in at home.”

From a public health standpoint, being able to recognize the symptoms of mental illness, or mental health literacy, is critical. When a community is unfamiliar with symptoms or manifestations of mental illness, people are less likely to recognize their symptoms and take steps to seek help.

In Guarnaccia’s view, “Overall, people with less education from lower socioeconomic classes have less access to information about all of the different kinds of mental illnesses.” He added that such information gaps mimick the treatment gaps that socioeconomic disparities cause. “They have less of a resource-base from which to evaluate what’s going on when someone has a mental illness,” he said.

The public schools could be providers of mental health education, but school psychiatrists or administrators are spread too thin to address all the needs of so many students. And when public schools are funded by local property taxes, poor communities have less money to pay teachers, let alone to pay for more mental health professionals.

Jacqueline Paulino has worked as a bilingual school psychologist for the New York City Department of Education for more than 15 years. In her mid-forties, Paulino divides her time between two public primary schools in the Bronx, helping parents and teachers identify students’ possible learning disabilities and collaborating with teachers and parents on Independent Educational Plans, or IEPs. The school where I met Paulino, P.S. 246 Poe Center, has a population of more than 700 students and is listed as being at 112 percent capacity. Almost 90 percent of Poe Center’s students qualify for free or reduced price meals, and 34 percent are English language learners.

Paulino said that even though her title is school psychologist, she rarely gives consultations with teachers outside of the IEP or disability context. Her job description does not often make use of her master’s level education in psychology to deal with a child who may have mental health issues. When students are referred to her, it is usually because they are missing their learning benchmarks or demonstrating signs of a disability. There are few resources for children who may be struggling with psychological or emotional issues. They may not be aware of the help they are entitled to receive with a referral from teachers or social workers.

“We should be counseling and consulting with teachers if the child needs help,” Paulino said of school psychologists. “But the social workers are more trained to deal with them directly and our caseload is so high that we only have time to do evaluations and help develop IEPs.”

All the same, schools in lower income areas are less likely to guide their students toward mental health care, limiting students’ ability to find it normal to talk to a therapist or to take antidepressants. Consequently, mental illness can remain untreated and compound its negative impact when sufferers do not seek or know they need care.

Aless’s experience bears this out.”In my home life, mentions of mental illness at met with laughs. At school in my hometown, it is barely regarded with respect by the teachers. They subscribe to society’s perspective that some people just need to grow up,” Aless said. “Students get no real understanding even of the distinction between the different conditions a person could have. No one would learn the difference between simple manic states versus troubling erratic symptoms, for example. There is no ill will in my hometown against people who are struggling, just a lack of comprehension that can lead to insensitive behavior.”

Another issue emanating from untreated mental illness the impact in can have on long-term physical health. Carrie, the 33-year-old with severe anxiety bipolar disorder, said she knows well the physical toll that mental illnesses can take because of the decade without treatment.

“It destroyed my body,” Carrie said. “I have stomach damage, I have kidney damage, my brain quite literally is damaged, because when you have bipolar or the manifestations of severe anxiety, your adrenal glands become overactive. You’re constantly in fight or flight syndrome. It destroys your body because your body is trying to fight it. It destroyed my ovaries and I wound up with severe scar tissue over everything. My stomach lining has been eaten up by constant nausea.” She also said the adrenaline releases and subsequent reproductive organ scarring related to her untreated anxiety ultimately meant she and her husband could not naturally have their own children. “I would say that it’s pretty likely that [mental illness] cost of me having kids, and I’m fairly ongoingly bitter about that,” Carrie said.

Her worry about physical issues in later life is not unfounded. Some of the most compelling research on the effects of untreated emotional or mental health needs are the studies on Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs. Originally discussed in a joint study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente in the 1990s, ACEs are significant risk factors for later medical and mental health problems, including heart disease, depression, and diabetes.

While not mental illnesses in and of themselves, research on ACEs can also be applicable to the physical processes that occur when mental illnesses go untreated. When children experience ACEs, such as neglect or abuse, their bodies can react to chronic stress throughout childhood and into adulthood by inhibiting growth, increasing risk for cancer, certain diseases, and an increase in the likelihood of illicit drug use. Trauma’s relationship to mental illness is also well documented, most notably in its role in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, which is often seen in combat veterans, rape survivors and others who have experienced or witnessed a life-threatening event. But even if children experience an ACE and toxic stress without developing PTSD, the experience can alter not only their physical and mental health, but also the way their brains function and develop.

When a child experiences multiple ACEs, that also create a “dose-relationship” with other health issues, meaning that a person who has more ACEs is more likely to be at risk for medical, social, or behavioral problems. So although nearly 60 percent of adults may have at least one ACE, the negative health outcomes are compounded among the smaller proportion of people who have multiple ACE factors. For example, Stephanie, Aless, or Carrie, with ACE scores that include persistent mental illness, divorce, and exposure to family members’ substance abuse or other instabilities, have bodies that are at a much higher risk for serious health problems such as obesity, cancer, or bone fragility later in life.

Carrie, for one, is dealing with the consequences of her earlier lack of a mental health care plan. “The period that I was untreated because I could not afford to have treatment has probably shortened my lifespan by maybe ten years,” she said.

The way Carrie described the physical effects of her period without treatment mirrors the way ACEs have been shown to affect the endocrine system. Long periods of high stress in response to ACEs or mental illness symptoms mean that cortisol (a hormone that is released during fight-or-flight responses) is continuously released into the body, disrupting delicate hormonal balances that affect growth and metabolism. The constant release of stress hormones can also affect reproductive health, like it did with Carrie.

One study found that increased stress influenced women’s menstrual cycles, with 33 percent of the sampled incarcerated women under high stress reporting irregular periods, compared to the national average of 13 percent of women who reported experiencing irregular periods. Over time, hormonal irregularity from chronic stress can affect fertility, costing women like Carrie the opportunity have children in addition to adversely affecting their health overall.

In her book, The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity, Dr. Nadine Burke-Harris details her work integrating her patients’ ACE scores (the number of ACEs encountered before their 18th birthday) with their primary health care. She first found the 1990s-era CDC/ Kaiser Permanente study while working at a health clinic in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood. Patients would occasionally come in with seemingly inexplicable symptoms, such as stunted growth and development that was unresponsive to changes in diet or supplements.

“The ACE study is powerful for a lot of reasons, but a big one is that its focus goes beyond behavioral or mental health outcomes,” Burke-Harris writes. “Most people intuitively understand there’s a connection between trauma in childhood and risky behavior, like drinking too much, eating poorly and smoking, in adulthood. But what most people don’t recognize is that there is a connection between early life adversity and well-known killers like heart disease and cancer. Every day in the clinic I saw the way my patients’ exposure to ACEs was taking a toll on their bodies. They may have been too young for heart disease, but I could certainly see the early signs in their high rates of obesity and asthma.”

Even though her book predominantly discusses the case studies she examined while working a low-income community health center, Burke-Harris consistently warns against lumping ACEs and their subsequent health issues in together with poverty. Although the young people who came to her practice were at a higher risk for being exposed to trauma from gang violence or having incarcerated family members, ACEs were by no means a poverty-exclusive problem.

“While I knew all too well that poor communities experienced higher doses of adversity, I was worried that the issue was being framed as a ‘poor-people problem,'” Burke-Harris writes in her book. But while community stressors like growing up in an impoverished neighborhood can influence health outcomes, Burke-Harris argues that ACEs can, and do, happen to people regardless of class or race.

Carrie’s mental illness and the effects of her prolonged inability to treat it have created numerous challenges that she and her husband must face, but she said their inability to start a family lays the heaviest emotional burden.

She said that her mental illness not only interfered with her ability to have her own biological children, but that it also prevents her from starting a family through other means. “We can’t adopt because you can’t — no reputable [adopting agency] will go with somebody who has a bipolar 2 diagnosis. It’s just a fact of life,” Carrie said.

“You can say all you want that, ‘well you be great parents anyway,'” she explained further. “But if you’ve got, as always, childless couples who are lining up, people who are equal to us in most ways but, first of all, will usually make more money because they’re in a better place to do that, but also the same as us in every way except they’re healthy, you’re going to go with that.”

While adoption agencies and state regulators don’t explicitly prohibit those with mental illnesses from adopting children, it is something that is usually taken into account in the adoption process. Before a child is placed with an adoptive family, states typically require a home study to evaluate the family’s ability to provide and care for the adopted child. Home studies typically involve one-on-one interviews, home visits, and criminal history checks. And in 18 states and American Samoa, home study evaluations also require the prospective parent’s mental health information when determining their eligibility for adoption. An applicant’s mental health history isn’t always a deal breaker, but adoption providers nonetheless bring mental health criteria into their consideration process.

Adoption discrimination against mental illness sufferers like Carrie isn’t outright, but the fear of discrimination is very real. A Google search for “adoptive parent mental illness” will come up with dozens of articles, blog posts, and forum discussions on whether disclosure of mental illness will cost an individual or couple the ability to adopt. Answers range from hopeful to pessimistic, “The agency only wanted to know that I am stable and what I do to remain stable. It was no problem at all,” wrote one commenter. “We were honest with the County we are working with and so far, the reaction is only negative,” wrote another prospective parent. “It is trying when you have one division of the County approving your application to move forward and therefore look like they are not prejudice of mental illness and then the next group only has to deny you for “not being the best fit.”

For Stephanie, the 22-year-old aspiring artist, fear of discrimination was her family’s largest deterrent to her seeking help for her. Lack of money and cultural stigma both strengthened her parents’ argument against pursuing mental health care, but the most significant factor was the fear that, if she were diagnosed, she wouldn’t be able to claim guardianship of her younger brother if her parents died unexpectedly or otherwise were absent from their children’s lives.

Her brother is now at an adult age, but his disability makes it impossible for him to live on his own. Stephanie already has taken on a great deal of her brother’s care. She helps her mother administer his cerebral palsy medication and feed him his meals. In her parents’ minds, documenting Stephanie’s mental illness with a diagnosis or treatment would be tantamount to dooming their younger, disabled child to be a ward of the state.

“I don’t think it’s wholly a financial problem,” Stephanie said of her inability to seek treatment. “It’s more that they’re scared about the whole guardianship thing, and to let other people in my family know about [my illness].”

I asked if her family had ever sought a legal opinion or done research on obtaining legal guardianship while treating a mental illness, but Stephanie said even just the prospect of her being denied the ability to take responsibility for him was enough to scare her parents away from treatment for her.

I asked Dr. Guarnaccia if he’d ever heard of a situation like Stephanie’s. He did not answer specifically, but offered, “That’s the challenge. It’s not that the fears aren’t real. The assessments may not actually be accurate, but in that kind of a case, it may prevent people from seeking treatment because they don’t want it on their medical record or they’re afraid somebody might find it and use it against them.”

Ultimately, people like Stephanie, Carrie, and Aless have to make do with the resources that they have, however flawed or inadequate they may be. ACA, for the time being, has at least mitigated the most tangible hurdle, financial cost. But many challenges still remain. Dr. Guarnaccia said that on a more broader scale, developing more mental health education in underserved communities will be crucial in addressing mental illness as a public health issue in years to come.

“There’s a lot to be done on education about mental illness and particular education about medication treatment,” he said. “We have to have people treat the disease just like any other, and focus on that it’s really not your fault. We don’t have as good an understanding of where mental illnesses come from as we would like. Compared to something like hypertension, we have an idea of what it is and how to treat it, but for mental illness that’s a lot less clear.”

She is a 21-year-old community college student in graphic design who has suffered from anxiety and depression since she was eight years old. She lives in a modest frame house in Paterson, New Jersey, with her parents and her brother, who has cerebral palsy. Stephanie, who asked to be identified only by her first name, does what she can to address her symptoms. From internet forums, for instance, she has learned to stave off the onset of panic attacks by taking three long breaths to keep her from hyperventilating.

Professional help, she said, has never been an option, not even after she was hospitalized overnight at age 13 because a classmate overheard her contemplating suicide.

In Stephanie’s family, other financial burdens have kept her mental health from being a priority. Her father works as an auto technician; her mother stays at home to tend to her younger brother’s needs, feeding him every four hours and administering his medication several times a day.

Beyond the breathing technique, Stephanie’s art is her main coping mechanism. When she draws or paints, she said, she’s able to “let everything go.” It also gives her a way to earn money from freelance art commissions to help pay for her college classes two days a week. Her parents help cover the rest of her costs, which range from $300 to $1,000 per class.

The teenaged hospitalization episode could have been the turning point for her to begin professional mental health care. Doctors at the time identified her symptoms. They made a preliminary diagnosis and urged her parents to follow up by seeking professional help for her. They even threatened to report the family to Child Protective Services if they did not. Her parents agreed but only to secure her release from the hospital. “It was out of the question,” Stephanie said. “We couldn’t afford it.”

Not even a sliding scale payment scheme would have made consistent treatment for Stephanie possible. Given the invisibility of her illness, it was hard for her family to understand its urgency. She said that not only would her family struggle with the financial burden of treatment, but their own cultural beliefs saw mental illness as weakness rather than as a medical condition. This attitude is not uncommon in their Latino community in Paterson, which has an average annual income of $32,915.

Stephanie’s situation puts her among the 20 percent of American adults who experience mental illness, and also among those without the resources to confront the difficulties their condition presents. As hard as mental illness can be for anyone to face, poverty dramatically exacerbates its impact on the individual.

A 2015 study by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention found that among US adults, a decrease in income level correlated with an increase in serious psychological distress. Individuals may be able to find emergency short-term help at no cost, but sustained reliable treatment is rarely possible for the economically disadvantaged. The barriers are not always seen: from the cost of medication to the cultural stigmas that discourage therapy and prevent individuals like Stephanie from seeking professional care. Others are afraid of the discrimination that may result from their diagnoses. As a result, the poor who suffer from mental illness must make do with limited resources, worsening both their health and their financial insecurity.

Cost is the most obvious impediment to treatment. It is sometimes a trigger for anxiety itself. For Carrie, a 33-year-old living in Minnesota, her fear of being denied coverage for her mental illness prevented her from seeking treatment for more than 10 years.

Carrie’s paternal family had a history of bipolar disorder, and her mother’s family is “full of depressives,” many of whose lives ended in suicide. On particularly rough days, Carrie said she feels as if she is doomed to repeat the fate of her grandparents and several other relatives, who died after their untreated mental illnesses made them reclusive hoarders.

“I remember how my aunt died, and trying to clean out her house by literally wading through waist-high garbage,” Carrie said, calling the experience one of the most horrible days in her life. “So there’s a sense of, ‘Is there a script? Is there nothing I can do to not follow?’ Will I end up like my grandfather and my grandmother, who let themselves die from neglect?”

Carrie, who grew up in Maryland, had experienced bipolar disorder’s telltale swings of depression and mania since she was in high school, but didn’t seek treatment at that time. Her mother worked as a school administrator and her father was frequently in and out of work due to his own mental health. Carrie’s parents did not see mental illness as the reason for the behavior patterns in the family and that discouraged her from seeking help.

In college, Carrie’s depressive to manic mood swings had her alternating between acing and failing her courses until she dropped out of school. At 21, a stranger entered Carrie’s home and sexually assaulted her. That prompted the State of Maryland to pay for her therapy and counseling, during which the therapist suggested a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Carrie asked the therapist not to include a diagnosis in his notes — she was uninsured and knew that bipolar disorder would be considered a pre-existing condition that would complicate her ability to obtain health insurance in the future.

“I said, ‘You cannot write that down,’” Carrie remembered, and he understood. “I could not afford the medication and if I had that on my record, it’s possible I would never get health insurance, period.”

Before the passing of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder were considered pre-existing conditions. More than 30 states allowed insurance companies to use these conditions—everything from postpartum anxiety to acne—to increase premiums or deny coverage. One study found that premiums were raised as much as 50 percent for someone with depression. Although these provisions did not specifically target people with mental illness, insurance companies often used such diagnoses to increase the cost of care before the ACA. In effect, the treatment that should have been helping those with mental illness created even more worry.

In 2005, when Carrie began therapy, she had already heard horror stories from those seeking insurance with pre-existing conditions and knew that some therapists would go so far as to change a diagnosis from, say, borderline personality disorder to bipolar disorder, so that it would seem like a new condition and thus side-step future insurance issues. “I had a friend who had that happen to her,” Carrie said. “And when she changed health insurance from job to job, her therapist had to invent new diagnoses for her each time.”

Carrie said her friend’s medication also changed with each new diagnosis, ineffectively treating her illness. The state of Maryland provided her with free counseling after she was assaulted, but when she moved to Minnesota, the coverage did not travel with her. She did not want to jump between diagnoses, and knew she could not afford $600 to $700 dollars worth of psychiatric medication each month on her own. So at that point, she opted for no treatment or medication at all.

Carrie married in 2007 and one year later, her husband got a job at IKEA, which provided both of them with health care benefits. Having insurance enabled Carrie to get an official diagnosis of bipolar II disorder and severe anxiety. Since then, Carrie receives psychiatric evaluations every few months and takes a mood stabilizer, an antidepressant during the winter months for symptoms of seasonal affective disorder, and the occasional anxiety sedative.

Even though both Carrie and her husband have found stable work, the couple still faces financial complications. Halfway through our first interview, Carrie fielded a call from a debt collection agency. “I don’t feel like taking it,” she said. While her husband’s job pays their bills and provides essential health coverage, there are not many advancement opportunities at the home store conglomerate. Still, Carrie’s husband stays with the company because the health insurance is so vital, and Carrie’s medication is too valuable to risk.

While the ACA has protected people like Carrie since 2014, efforts to repeal it create worries about maintaining treatment and medication in the foreseeable future. If repealed, Carrie could lose her coverage if her husband switches jobs, or if IKEA changes providers. Losing Obamacare could also mean increased premiums with their existing plan. These anxieties, Carrie said, pile onto the already existing symptoms of her illness.

“That’s where poverty locks you in,” Carrie said. “It tied my husband to this job until Obamacare because if he left the job, he knew that I would probably maybe last six months before I killed myself. Even though he had offers that would have been theoretically for better jobs, he couldn’t take them.”

Carrie’s stress over paying for both her medication and bills is not a singular experience, but it’s a common stressor among those struggling with mental illness and poverty.

A 2016 study by the Money and Mental Health Policy Institute found that adults with depression and problem debt (a sign of financial instability) were more than four times more likely to have depression symptoms after 18 months than those without problem debt. The institute also found that for anxiety, those with financial instability were 1.8 times more likely to still identify with the disorder 18 months later than those with dissimilar socioeconomic factors.

The same study reported that more than 80 percent of the survey’s 5,500 respondents with mental health problems said their financial situation had made their mental health problem worse. For those with depression, financial woes can worsen feelings of helplessness. For people like Carrie, who experience immense anxiety in their everyday lives, the added pressure to make ends meet foster anxious thoughts.

“Money is a huge issue, it’s very anxiety inducing.” Carrie said. “I can’t open my checking account to just look at how much money we have.”

Carrie also described how her anxiety and money concerns compound one another when dealing with the day-to-day necessities like keeping house. She said having a mental illness is like arriving at a speed bump. Those without mental illness are able to recognize obstacles and slow down accordingly, but for Carrie, her anxiety makes her view the speed bump as a road-block she cannot react to quickly enough or well enough.

“I’m frequently living in the kind of situation where you don’t let people come over because it’s too embarrassing,” she said. “Our sink has not been draining for about a year, so we have it run into a bucket which I empty into the toilet. I would rather deal with that than call a plumber and find out we can’t afford it.”

Carrie and others like her are protected by ACA for now, despite attempts to repeal it through the 2017 American Health Care Act that passed in the House of Representatives but never made it to a Senate vote. But with a president in office who campaigned on the promise to repeal ACA and Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, a future attempt to remove protections for those with pre-existing conditions is more likely than not to become law. Given the uncertain future of health policy, Carrie said she wouldn’t know what to do if faced with the choice between necessary, expensive treatments and her other financial obligations.

“With the laws being what they are, anything could happen at any moment with the government,” Carrie said. “Obamacare could leave. And then who knows what would happen?”

Less visible impediments to obtaining the care an individual needs often come from a combination of family and community norms. Stephanie, the graphic designer, for example, said her Latino family’s conservative views may not have been the primary block to her seeking help, but they did make doing so more difficult. It was hard for her to talk to her parents about what she was experiencing. “When you’re from a family that doesn’t really talk about mental illness ,“ she said, “it kind of becomes taboo.”

I asked if she had any sort of support system beyond her family — if not a therapist, perhaps a local support group of some kind. She said no. If there were organized mental health resources in Paterson, she was not aware of them. She does, however, have one friend she can confide in, who also grew up in Paterson. Aless V. is a 21-year-old film and television production student at New York University who has had ADHD since she was five years old and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder last year. The two young women sometimes share confidences and support one another.

Aless’s parents escaped severe hardship and poverty in Peru to immigrate to the United States when she was a young child. As with Stephanie, manifestations of Aless’s condition also appeared early on in life. But in Aless’s case, her family’s memories of life in South America dominated their views on mental illness. Aless felt that the difficulties she was experiencing in and out of school simply paled by comparison to what her parents had endured before they came to the United States.

“I think my parents are very empathetic people,” Aless said. “I think they understand when I’m in pain, but if I’m just saying, ‘I’m struggling with this’ or ‘This is making me anxious,’ I don’t think they have a grip on what that means.”

Not only was their lack of understanding a block, but when Aless was 10, her parents divorced, sending the family below the poverty line for a couple of years. Her mother, who was uninsured at the time, became the children’s primary source of support and even if she had been inclined to seek professional help for her daughter, she could not have afforded it. On top of that was the cultural stigma Aless said her community ascribes to mental health treatments like therapy or medication. The power of mental health stigma is well documented in its ability to dissuade those needing help from seeking it.

As Aless explained it, her family and neighbors in Paterson “associate therapy with mental clinics, which they would call loony bins. It’s such an outdated term, but even in a community that’s so heavily people of color, mostly black and Latino, words like that are what we got out of American culture. That’s one of the things that sticks.”

Aless explained that in her community, caring too much about one’s mental state is seen as an indulgence or a sign of weakness. “To care would be considered taking it too seriously,” she said, “or you’re thinking too much into it.” That wasn’t to say depression and anxiety weren’t common in the community, but that talking about it was the taboo. In Paterson, Aless said, “There’s a general culture that says, ‘Suck it up,’ the only way for you to feel better about suppressing your own pain is to tell others to do the same thing.”

Nevertheless, despite all the impediments, when the family’s financial situation stabilized years later, her parents did allow her to seek help. Aless saw a therapist, who prescribed medication that she has been taking ever since. So in her view, help “came with money,” she said. “It came with access, and, like, better security. I started going to doctors.

“There’s a difference when you don’t have money to deal with something,” she went on. “You pretend the problem doesn’t exist, and the moment you have the money to deal with it, you remember that it exists.”

Dr. Peter Guarnaccia is a medical anthropologist at Rutgers University who researches mental illness in Latino communities. He said Aless’s and Stephanie’s experiences with stigma were typical of the attitudes he has encountered in other such cases. Cultural stigmas on mental illness are not unique to Latinos, he said, but they can be a particularly strong force within these communities.

Echoing Aless, he said, “I think there is also this idea of, ‘It’s up to you to get over on your own,’ the idea that it’s almost a moral failing rather than an illness is also part of it. I think class, gender, culture all interact together to affect that.”

In a 2006 paper Guarnaccia co-authored, “‘It’s Like Going through an Earthquake’: Anthropological Perspectives on Depression among Latino Immigrants,” he particularly examined the cultural barriers to mental health care faced by immigrants. Participants in his focus groups would face and overcome financial and bureaucratic obstacles to treatment, only to be ostracized in their communities. Twelve years after the study’s publication, Guarnaccia still remembers one woman from the focus group who was finally able to seek treatment, only to have her neighbors call her “la loca,” or the crazy woman, when she returned home from therapy.

“I think the challenge is that [people think] if you’re not mentally healthy, you’re loco, or crazy, and there isn’t a lot of understanding of all the different ways of having mental health problems in between,” Guarnaccia said. “In many Latino countries, mental health services aren’t widely available. So people don’t really understand what they are. What people do know is that there are hospitals for people with serious mental issues. That’s their understanding of it.”

Aless regularly saw these misunderstandings of mental illness in her hometown when trying to find support for her anxiety and ADHD. “If you’re going to doctor, getting any help whatsoever, then you have to be crazy, you have to be certifiable,” she said, saying there wasn’t any recognition that someone could function well while dealing with their mental illness. “With older generations,” she said, “it’s worse. A lot of them being immigrants from countries with an even stronger stigma, they teach children to suppress symptoms and can’t really comprehend what these people are going through. It is out of fear more than it is out of judgment.”

Cultural views on values such as control and hardiness can cause further isolation for individuals experiencing mental illness or even self-stigmatization. Guarnaccia spoke of the work of a colleague of his, Roberto Lewis-Fernández, who has studied the importance in Latino culture of being in control. “One of the scariest ways to be ill is to be out of control,” Guarnaccia said. “ That kind of feeling is seen as very, very serious.”

Guarnaccia and Lewis-Fernández have studied ataques de nervios, a syndrome similar to panic attacks that is known to affect Caribbean Latinos. Guarnaccia said that one of the condition’s key features is the loss of emotional, physical, cognitive control. “Roberto particularly emphasized that that’s really the kind of core issue in ataques de nervios. Being mentally ill is being out of control and that scene is very scary both internally when someone feels that way, but also by the community at large.”

Ultimately, Guarnaccia thinks that addressing cultural stigmas in these groups is crucial to improving their community mental health care models. Culture, he said, can be a reason why a community might reject certain methods of treatment, like psychiatric medication, and understanding common misconceptions can help create more culturally competent care.

Citing the reactions of Latino immigrants in his focus groups, he noted another aspect of the tendency to stigmatize: “People feel like the medications are very dangerous, that they can be addictive,” Guarnaccia said. ” In their home countries, the medications that are available often are some of the older medications, at least for people who are using the public mental health system, older medications which can be more addictive than the newer medication. And they don’t realize the differences. So it’s the stigma of mental illness, but it’s also the stigma of treatment.”

Aless said that in her case, as disinclined as her parents were to putting her on medication, they still preferred pills to talk therapy. “So even with years and years of experience, they still don’t know about why my illness exists or what it is. All they can ever see is the physical aspect: my grades went up when I started taking medication, so that medication is helping. But they don’t understand there’s a condition that is the source.”

Stephanie and Aless did not go to the same public high school. Thanks to scholarships, Aless was able to attend DePaul Catholic High School, a private school in Wayne, NJ, where the median household income was three times that of families in Paterson. At DePaul, seeing therapists was commonplace among Aless’ more privileged classmates. That experience gave her access to far more information about mental health issues than had been available in her home community. It also gave her far more acceptance of her condition than was available to Stephanie or most of her other hometown peers.

“Seeing the way wealthier students were treated for their own conditions at least informed me of the impact that mental illness can have on a person regardless of their circumstances,” Aless said. She still experienced bullying and isolation in her new school, and the helpful changes in her behavior came with some undesirable side effects. Nonetheless, “Even if the social aspect of it was quite unpleasant and biased,” Aless said, “at least the teachers and staff recognized the prevalence of problems. This built up my understanding of mental illness and at least gave me a realistic take on how the world sees mental illness in a demographic other than the one I lived in at home.”

From a public health standpoint, being able to recognize the symptoms of mental illness, or mental health literacy, is critical. When a community is unfamiliar with symptoms or manifestations of mental illness, people are less likely to recognize their symptoms and take steps to seek help.

In Guarnaccia’s view, “Overall, people with less education from lower socioeconomic classes have less access to information about all of the different kinds of mental illnesses.” He added that such information gaps mimick the treatment gaps that socioeconomic disparities cause. “They have less of a resource-base from which to evaluate what’s going on when someone has a mental illness,” he said.

The public schools could be providers of mental health education, but school psychiatrists or administrators are spread too thin to address all the needs of so many students. And when public schools are funded by local property taxes, poor communities have less money to pay teachers, let alone to pay for more mental health professionals.

Jacqueline Paulino has worked as a bilingual school psychologist for the New York City Department of Education for more than 15 years. In her mid-forties, Paulino divides her time between two public primary schools in the Bronx, helping parents and teachers identify students’ possible learning disabilities and collaborating with teachers and parents on Independent Educational Plans, or IEPs. The school where I met Paulino, P.S. 246 Poe Center, has a population of more than 700 students and is listed as being at 112 percent capacity. Almost 90 percent of Poe Center’s students qualify for free or reduced price meals, and 34 percent are English language learners.

Paulino said that even though her title is school psychologist, she rarely gives consultations with teachers outside of the IEP or disability context. Her job description does not often make use of her master’s level education in psychology to deal with a child who may have mental health issues. When students are referred to her, it is usually because they are missing their learning benchmarks or demonstrating signs of a disability. There are few resources for children who may be struggling with psychological or emotional issues. They may not be aware of the help they are entitled to receive with a referral from teachers or social workers.

“We should be counseling and consulting with teachers if the child needs help,” Paulino said of school psychologists. “But the social workers are more trained to deal with them directly and our caseload is so high that we only have time to do evaluations and help develop IEPs.”

All the same, schools in lower income areas are less likely to guide their students toward mental health care, limiting students’ ability to find it normal to talk to a therapist or to take antidepressants. Consequently, mental illness can remain untreated and compound its negative impact when sufferers do not seek or know they need care.

Aless’s experience bears this out.”In my home life, mentions of mental illness at met with laughs. At school in my hometown, it is barely regarded with respect by the teachers. They subscribe to society’s perspective that some people just need to grow up,” Aless said. “Students get no real understanding even of the distinction between the different conditions a person could have. No one would learn the difference between simple manic states versus troubling erratic symptoms, for example. There is no ill will in my hometown against people who are struggling, just a lack of comprehension that can lead to insensitive behavior.”

Another issue emanating from untreated mental illness the impact in can have on long-term physical health. Carrie, the 33-year-old with severe anxiety bipolar disorder, said she knows well the physical toll that mental illnesses can take because of the decade without treatment.

“It destroyed my body,” Carrie said. “I have stomach damage, I have kidney damage, my brain quite literally is damaged, because when you have bipolar or the manifestations of severe anxiety, your adrenal glands become overactive. You’re constantly in fight or flight syndrome. It destroys your body because your body is trying to fight it. It destroyed my ovaries and I wound up with severe scar tissue over everything. My stomach lining has been eaten up by constant nausea.” She also said the adrenaline releases and subsequent reproductive organ scarring related to her untreated anxiety ultimately meant she and her husband could not naturally have their own children. “I would say that it’s pretty likely that [mental illness] cost of me having kids, and I’m fairly ongoingly bitter about that,” Carrie said.

Her worry about physical issues in later life is not unfounded. Some of the most compelling research on the effects of untreated emotional or mental health needs are the studies on Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACEs. Originally discussed in a joint study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente in the 1990s, ACEs are significant risk factors for later medical and mental health problems, including heart disease, depression, and diabetes.

While not mental illnesses in and of themselves, research on ACEs can also be applicable to the physical processes that occur when mental illnesses go untreated. When children experience ACEs, such as neglect or abuse, their bodies can react to chronic stress throughout childhood and into adulthood by inhibiting growth, increasing risk for cancer, certain diseases, and an increase in the likelihood of illicit drug use. Trauma’s relationship to mental illness is also well documented, most notably in its role in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, which is often seen in combat veterans, rape survivors and others who have experienced or witnessed a life-threatening event. But even if children experience an ACE and toxic stress without developing PTSD, the experience can alter not only their physical and mental health, but also the way their brains function and develop.

When a child experiences multiple ACEs, that also create a “dose-relationship” with other health issues, meaning that a person who has more ACEs is more likely to be at risk for medical, social, or behavioral problems. So although nearly 60 percent of adults may have at least one ACE, the negative health outcomes are compounded among the smaller proportion of people who have multiple ACE factors. For example, Stephanie, Aless, or Carrie, with ACE scores that include persistent mental illness, divorce, and exposure to family members’ substance abuse or other instabilities, have bodies that are at a much higher risk for serious health problems such as obesity, cancer, or bone fragility later in life.

Carrie, for one, is dealing with the consequences of her earlier lack of a mental health care plan. “The period that I was untreated because I could not afford to have treatment has probably shortened my lifespan by maybe ten years,” she said.

The way Carrie described the physical effects of her period without treatment mirrors the way ACEs have been shown to affect the endocrine system. Long periods of high stress in response to ACEs or mental illness symptoms mean that cortisol (a hormone that is released during fight-or-flight responses) is continuously released into the body, disrupting delicate hormonal balances that affect growth and metabolism. The constant release of stress hormones can also affect reproductive health, like it did with Carrie.

One study found that increased stress influenced women’s menstrual cycles, with 33 percent of the sampled incarcerated women under high stress reporting irregular periods, compared to the national average of 13 percent of women who reported experiencing irregular periods. Over time, hormonal irregularity from chronic stress can affect fertility, costing women like Carrie the opportunity have children in addition to adversely affecting their health overall.

In her book, The Deepest Well: Healing the Long-Term Effects of Childhood Adversity, Dr. Nadine Burke-Harris details her work integrating her patients’ ACE scores (the number of ACEs encountered before their 18th birthday) with their primary health care. She first found the 1990s-era CDC/ Kaiser Permanente study while working at a health clinic in San Francisco’s Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood. Patients would occasionally come in with seemingly inexplicable symptoms, such as stunted growth and development that was unresponsive to changes in diet or supplements.

“The ACE study is powerful for a lot of reasons, but a big one is that its focus goes beyond behavioral or mental health outcomes,” Burke-Harris writes. “Most people intuitively understand there’s a connection between trauma in childhood and risky behavior, like drinking too much, eating poorly and smoking, in adulthood. But what most people don’t recognize is that there is a connection between early life adversity and well-known killers like heart disease and cancer. Every day in the clinic I saw the way my patients’ exposure to ACEs was taking a toll on their bodies. They may have been too young for heart disease, but I could certainly see the early signs in their high rates of obesity and asthma.”

Even though her book predominantly discusses the case studies she examined while working a low-income community health center, Burke-Harris consistently warns against lumping ACEs and their subsequent health issues in together with poverty. Although the young people who came to her practice were at a higher risk for being exposed to trauma from gang violence or having incarcerated family members, ACEs were by no means a poverty-exclusive problem.

“While I knew all too well that poor communities experienced higher doses of adversity, I was worried that the issue was being framed as a ‘poor-people problem,'” Burke-Harris writes in her book. But while community stressors like growing up in an impoverished neighborhood can influence health outcomes, Burke-Harris argues that ACEs can, and do, happen to people regardless of class or race.

Carrie’s mental illness and the effects of her prolonged inability to treat it have created numerous challenges that she and her husband must face, but she said their inability to start a family lays the heaviest emotional burden.

She said that her mental illness not only interfered with her ability to have her own biological children, but that it also prevents her from starting a family through other means. “We can’t adopt because you can’t — no reputable [adopting agency] will go with somebody who has a bipolar 2 diagnosis. It’s just a fact of life,” Carrie said.

“You can say all you want that, ‘well you be great parents anyway,'” she explained further. “But if you’ve got, as always, childless couples who are lining up, people who are equal to us in most ways but, first of all, will usually make more money because they’re in a better place to do that, but also the same as us in every way except they’re healthy, you’re going to go with that.”

While adoption agencies and state regulators don’t explicitly prohibit those with mental illnesses from adopting children, it is something that is usually taken into account in the adoption process. Before a child is placed with an adoptive family, states typically require a home study to evaluate the family’s ability to provide and care for the adopted child. Home studies typically involve one-on-one interviews, home visits, and criminal history checks. And in 18 states and American Samoa, home study evaluations also require the prospective parent’s mental health information when determining their eligibility for adoption. An applicant’s mental health history isn’t always a deal breaker, but adoption providers nonetheless bring mental health criteria into their consideration process.

Adoption discrimination against mental illness sufferers like Carrie isn’t outright, but the fear of discrimination is very real. A Google search for “adoptive parent mental illness” will come up with dozens of articles, blog posts, and forum discussions on whether disclosure of mental illness will cost an individual or couple the ability to adopt. Answers range from hopeful to pessimistic, “The agency only wanted to know that I am stable and what I do to remain stable. It was no problem at all,” wrote one commenter. “We were honest with the County we are working with and so far, the reaction is only negative,” wrote another prospective parent. “It is trying when you have one division of the County approving your application to move forward and therefore look like they are not prejudice of mental illness and then the next group only has to deny you for “not being the best fit.”

For Stephanie, the 22-year-old aspiring artist, fear of discrimination was her family’s largest deterrent to her seeking help for her. Lack of money and cultural stigma both strengthened her parents’ argument against pursuing mental health care, but the most significant factor was the fear that, if she were diagnosed, she wouldn’t be able to claim guardianship of her younger brother if her parents died unexpectedly or otherwise were absent from their children’s lives.

Her brother is now at an adult age, but his disability makes it impossible for him to live on his own. Stephanie already has taken on a great deal of her brother’s care. She helps her mother administer his cerebral palsy medication and feed him his meals. In her parents’ minds, documenting Stephanie’s mental illness with a diagnosis or treatment would be tantamount to dooming their younger, disabled child to be a ward of the state.

“I don’t think it’s wholly a financial problem,” Stephanie said of her inability to seek treatment. “It’s more that they’re scared about the whole guardianship thing, and to let other people in my family know about [my illness].”

I asked if her family had ever sought a legal opinion or done research on obtaining legal guardianship while treating a mental illness, but Stephanie said even just the prospect of her being denied the ability to take responsibility for him was enough to scare her parents away from treatment for her.

I asked Dr. Guarnaccia if he’d ever heard of a situation like Stephanie’s. He did not answer specifically, but offered, “That’s the challenge. It’s not that the fears aren’t real. The assessments may not actually be accurate, but in that kind of a case, it may prevent people from seeking treatment because they don’t want it on their medical record or they’re afraid somebody might find it and use it against them.”

Ultimately, people like Stephanie, Carrie, and Aless have to make do with the resources that they have, however flawed or inadequate they may be. ACA, for the time being, has at least mitigated the most tangible hurdle, financial cost. But many challenges still remain. Dr. Guarnaccia said that on a more broader scale, developing more mental health education in underserved communities will be crucial in addressing mental illness as a public health issue in years to come.

“There’s a lot to be done on education about mental illness and particular education about medication treatment,” he said. “We have to have people treat the disease just like any other, and focus on that it’s really not your fault. We don’t have as good an understanding of where mental illnesses come from as we would like. Compared to something like hypertension, we have an idea of what it is and how to treat it, but for mental illness that’s a lot less clear.”

![]()