Vital or Vain?

Can community media make a comeback?

by John Ambrosio

The studio at Manhattan Neighborhood Network.

I first walked into the television studios at the Manhattan Neighborhood Network on 59th Street in late April of 2014 to watch “The Chris Gethard Show.” This staple of the late-night comedy scene, attended that night by about 50 other people—mostly regulars, many in costume—was a New York City cult favorite, known for its adventures in experimental, participatory broadcasting. Under the direction of its eponymous host, past episodes have featured everything from a presidential debate with the Rent is Too Damn High Party’s Jimmy McMillan to the concoction and consumption of a milkshake made of whatever callers asked the hosts to throw into a blender.

Gethard’s show could only really happen at a place like MNN, which, as a public access station, gives airtime to anyone with an address ending in a Manhattan zip code. While the station’s programming does not always take the form of underground comedy or vomit-inducing smoothies, the basic idea behind public access is to facilitate whatever community producers decide to present. Whatever, in this case, includes things like the challenge-based art show “Let’s Paint TV,” in which the host John Kilduff takes calls and paints pictures while running on a treadmill, or the X-rated MNN party show, “SubZero TV,” which features hip-hop performances interspliced with gratuitously pornographic dance sequences. Above all else, says Alliance for Community Media president Mike Wassenar, public access is a platform where all comers gets to say and do what they want.

The Chris Gethard Show.

This directive has been in place since the launch of public access television more than 40 years ago. It puts the same tools the dominant mass media outlets use into the hands of people whose voices “real TV” normally excludes. “We may be living in a golden age of quality television,” said Wassenar. “But it’s not television that necessarily describes my world or your world or your needs.”

Public access is meant to address those needs, which would otherwise be ignored. As a result, local public access programming tends to reflect the community it serves. Middle-American public access stations, for example, “tend to have polka” shows, Wassenar said, simply because they would likely never been aired in media centers like Los Angeles and New York City.

Advocates like Wassenar, however, maintain that public access still serves the public good. He holds out hope that the challenges the medium faces will ultimately prove to be nothing more than growing pains that will help it evolve for the better.But, after decades of shows like Gethard’s—along with programming that range from the political and educational to spiritual and cultural—public access is facing some difficult questions about its future. Local governments have been slashing the budgets of public access television station and cable providers have lobbied hard for new legislation that would free them of their obligation to fund these shoestring operations. Some have argued that developments like the Internet might render public access television obsolete. Even the late Red Burns, who many consider the godmother of public access, eventually came to dismiss it derisively as nothing more than “vanity video,” as one of her protégés Dan O’Sullivan, recalled her saying.

“We may be living in a golden age of quality television,” said Wassenar. “But it’s not television that necessarily describes my world or your world or your needs.”

To grapple with these questions—and to understand what’s at stake, how public access is being threatened, and how serious that threat is—we need to examine the medium’s origins and purpose. But, before all that, let’s look at what happens when the tools of mass media are handed to everyday people.

Gethard’s show, which relies heavily on input from the in-studio audience, from callers, and from a live chatroom where viewers comment in real-time, is as good an example as any of what can happen when amateurs seize the airwaves.

True to form, the show was a chaotic mess that night two years ago. As soon as the cameras turned on, for no apparent reason, the audience began bellowing a chant “Eat more butts,” much to Gethard’s delight.

After about 10 minutes, the musical guest, a Brooklyn-based punk rocker named Jeff Rosenstock started playing a song that incorporated the audience’s pro-analingus message, prompting people to get up on their feet and yell the same chant even louder. When the crowd finally settled, Gethard offered only a meek, “Sometimes that’s how our show begins,” before beginning his planned intro. By then, he was 16 minutes into the hour-long program.

From there, the show fell back into its regular format, which consists of Gethard and his panel of fellow comedians fielding calls on some topic; this night, anxiety. One regular caller, known only as “Sudo,” used his airtime to make unintelligible noises while the panelists wondered aloud what he wanted from them. Minutes later, another caller named Paige called in to voice some of her fears and ask the panelists for life advice. Between the phone calls and the chanting and periodic check-ins with the chat room, the audience steered the show more than the host, which, yes, meant the whole thing ran into the rocks more than once.

The studio’s four HD cameras—operated by a volunteer staff made up mostly of art school students and other local comedians—captured the anarchic display. This debauched signal was sent to the sound booth down the hall and then relayed almost instantaneously through the same set of cables that Time Warner uses to deliver all its content to homes throughout Manhattan.

While it could be argued that “The Chris Gethard Show” meets the criteria of Burns’ “vanity video,” even the most skeptical viewer would find it hard to deny that there is something inherently exciting about amateurs making television. It is a bit like giving lit fireworks to a dog. It probably will go horribly, horribly wrong, but, when it succeeds in making something watchable, it’s that much more engaging because of how miraculous it is.

More importantly, “The Chris Gethard Show” parallels the spirit of what public access as a whole is meant to support: an open platform for the likes of Gethard, Paige, “Sudo,” and the studio audience. A place for everyone.

In his book, Public Radio and Television in America, Ralph Englemen describes the creation of public access television as “a historical accident,” that was, “the result of the confluence of social and technological development that spawned strategic if transitory alliances.” To put it in a way that the architects of public access might have preferred, public access was and is an experiment.

In 1970, a cadre of advocates capitalized on widespread public frustration over the closed-door negotiations then underway to establish a cable franchise in Manhattan. They pressured the Teleprompter Corporation cable company into making a last minute addition to its 20-year franchise contract for the borough. Teleprompter’s president at the time, Irving Khan, promised in this agreement that the company would “open our [two] public channels at no charge.” He promised to reserve them for noncommercial programming that any New Yorker could produce at the service provider’s expense.

The founding principle behind the agreement is that the airwaves—literally the spectrum of electromagnetic frequencies capable of carrying broadcast signals—are too precious and too scarce for any one company to own. They are, by default, a public good. To take advantage of this resource, the advocates argued, the television companies needed to give its owners—the public—some form of compensation, or rent.

So, a little more than a year later, in July of 1971, the first two public access stations opened for business, giving the people of New York City newfound access to this precious, unique resource.

Among those best positioned to take advantage of the deal were Burns and George Stoney, two filmmaker-educators who’d been involved with earlier participatory filmmaking experiments in Canada. Through the video group they co-founded, the Alternate Media Center at New York University, they brought together a team of documentarians and other filmmakers to generate interactive and community programming.

While their media center would eventually shift away from public access when it evolved into NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, O’Sullivan, the current ITP chair, said the program’s founders saw the start of amateur TV as a media revolution waiting to happen.

In 1967, Sony debuted its Portapak video camera, a camcorder precursor that was among the first consumer-grade portable cameras. When Burns saw this, O’Sullivan said, she realized video was going to change everything; “That’s going to change who can tell what stories.”

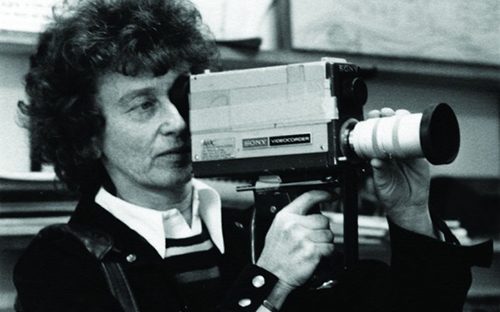

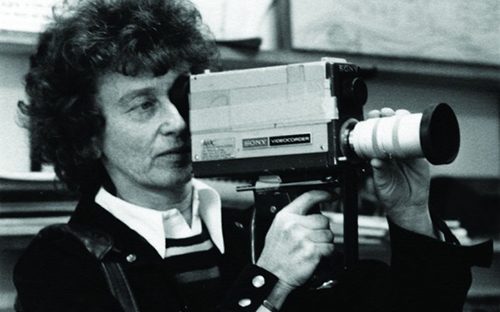

Red Burns with a Protapak camera.

Using this revolutionary technology, members of the collectives that operated out of the center went all around the city to gather some of those new stories. In an era still dominated by the four major networks, these community media pioneers distinguished themselves by concentrating on what the evening news ignored: small stories that mattered to everyday New Yorkers.

One early video made by Burns and her students, for example, was an hour-long documentary about a neighborhood in need of a new stop light. Using one of those revolutionary Portapacks, the students recorded the flow of traffic at the intersection and interviewed residents. When they’d finished the film, they showed the tape to city officials, who then acquiesced to the neighborhood’s requests. “This was really empowering and really convinced me that this had a lot of legs,” Burns said in an interview before her death in 2013.

These student collectives, along with three others founded by the New York State Council on the Arts—the Global Village, the Radiance Corporation and People’s Video Theater— were soon producing 200 hours of television a week for the two public access channels. All of these groups drew heavily on the successes and failures of earlier forays into the medium, some from professionally produced public television networks in the United States and Canada.

In March, 1972, the Federal Communications Commission issued its Cable Television Report and Order. Using the Teleprompter deal as a model, it mandated that all cable systems operating in markets with 3,500 or more subscribers establish noncommercial access stations for public, educational and governmental access.

Included in this mandate was the FCC’s assertion of regulatory control over cable. This, the commission believed, could be used to turn cable—partially through public access—into a medium that could facilitate “local expression,” “diversity,” “a sense of community to cable subscribers,” and “the functioning of democratic institutions.” The intention, in other words, was to create the 20th century version of the town square—a mass media-driven venue where ordinary people could gather for the exchange of ideas.

Public access advocates, like Burns and Stoney, saw this function as a vital contribution to modern, electrified society. O’Sullivan said at its best, public access mitigates some of the undesirable effects of mass communication. “Until television and film came along, media was pretty symmetrical,” O’Sullivan said, adding that media such as books, newspapers, and magazine, provided for a one-to-one relationship between creator and consumer. With the advent of film and television, the relationship became one-to-many, and limited access to the tools of media to the few. This is a problem, O’Sullivan said, because “the more democratically available the means of expression are, the healthier our society will be.”

The success of these early experiments encouraged more public access stations to crop up all over the country. Burns’ Alternate Media Center sent interns and apprentices to places like Bloomington, Indiana; Concord, New Hampshire; and Reading, Pennsylvania, and trained local facilitators. Even cable companies—eager to appeal to customers in markets where they had yet to gain a foothold—got in on the bonanza as a public relations tool. They provided the promise of public access as an incentive to get city and towns to sign onto their service.

“The more democratically available the means of expression are, the healthier our society will be.”

Durings the 1970s and 1980s, the relationship between local governments, public access centers, and cable companies evolved into what we know it as today. With a few exceptions until recently, each city or town managed its own community access outlet.

The funding that cable companies provided to public access stations comes from a “franchise fee,” or a fee levied by the municipality in exchange for having allowed the local cable franchise to operate. This fee is usually set at about five percent of the cable company’s total gross revenue from the town’s subscribers. The federal government also compelled cable companies to provide special funding directly to stations at a rate of about one percent of the cable company’s gross revenue in that local market. This one percent is known as Public, Educational, and Governmental funding—or PEG for short—and is restricted for use on “capital costs,” such as equipment and rental fees for studio space.

In 1992, Congress passed another Cable Act, clarifying earlier laws and making franchise fee money fungible, thus allowing local governments to spend it any way they chose. In times when local governments were strapped for cash, this meant that they could raid the public access stations for money to use on infrastructure, education, or anything else a city pays for.

Even still, for the next few years, public access television plugged along. From its origins in experimental video collectives in New York City, the medium soon entered the larger pop culture lexicon through movies like “Wayne’s World” and early MTV shows like “Squirt TV,” which originally ran on MNN and imitated the kitschiness of public access. A brief heyday in the 1980s and 1990s gave way to a whole new set of challenges as new companies entered the cable business.

With few exceptions, cable franchises have traditionally been negotiated on a local level, a direct result of how the cable industry developed. In the 1970s and 1980s, as cable lines and infrastructure stretched their way slowly from the cities to the hinterlands, each new municipal client got its own deal with a cable company. As a result, funding allocated for public access television varied from locale to locale. The more the town or city wanted a public access outlet, the more funding they would allocate to it in the deal.

Some states began to revise that model in the early 2000s, as telecom companies, particularly AT&T, attempted to expand in states like California. But the patchwork, town-by-town approach proved too costly and unwieldy. Instead, AT&T proposed a statewide model In California, this took the form of the Digital Infrastructure and Video Competition Act, known as DIVCA, which framed the argument for statewide franchising as a way to “encourage competition.” Before then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed DIVCA into law late in 2006, cable providers in California enjoyed exclusive domain over every town they served. The telecom companies contended that the arrangement constituted monopoly control. As an argument was a pretty easy sell. People love the free market almost as much as they hate their cable provider.

But, just to make sure things went as smoothly as possible, AT&T also spent $23 million on pro-DIVCA ads and political donations in the state of California in 2006. The bill’s sponsor—then-speaker Fabian Nuñez—was among the beneficiaries, collecting nearly $80,000 in direct donations from AT&T in 2005 and 2006. There were even accusations that Nuñez reaped indirect financial benefits for his support.

While Nuñez maintains his sponsorship of the bill grew out of his belief that it would drive healthy competition, several watchdog groups questioned his motives. After term limits forced him out of the statehouse in 2008, Nuñez accepted a job at Mercury Public Affairs, which did little to quell speculation, as client rolodex of the California-based consulting firm includes AT&T.

Even the big, bad cable companies like Time Warner and Comcast, which originally withheld their support for the measure, eventually became DIVCA proponents, even though it would cause them to lose control over local markets. This change of heart happened once the bill reached the State Senate, where lawmakers revised the bill, granting cable companies the same right to negotiate on a statewide level that was being proposed for the telecom companies. In other words, the right to negotiate on a statewide level is of greater value than a virtual monopoly over local markets. With this kind of support, the bill passed unanimously in the State Assembly and 33-4 in the State Senate.

The new law took effect in 2007 and also relaxed many of the earlier regulations, including those surrounding public access funding from cable companies. DIVCA did not eliminate, but loosened the need to pay local governments hundreds of thousands, even millions, of dollars to rent the airwaves from the people. As the San Francisco-based lobbyist Sue Buske said, “The only rent that goes back from the cable company to the local government is something called the franchise fee, and that’s capped by the federal government.”

Local governments, she said, have lost the right to negotiate for anything more. “In a lot of the states that this happened,” Buske said. “The state governments and the legislatures gave the cable operators a free pat. There’s very little oversight of the operation of the cable company.”

Sue Buske, media consultant and President of the Buske Group.

The cap on the franchise fee is 5 percent. This means that up to 5 percent of the provider’s gross revenue from customers in a given city goes back to that city’s government. In addition, DIVCA allows local entities to request PEG support of 1 percent of the holder’s gross revenues. So, in principle, as much as 6 percent of gross cable revenue could be given to access centers, although in practice, it rarely ends up being that much.

First off, cities and towns don’t always get the full 5 percent franchise fee. This is especially true in places where the cable providers make the franchise fees a line-item on monthly cable bills. That means the customer is often charged for a service that should be the company’s responsibility. The line item fee may even appear on the bills of customers whose cities don’t even operate public access stations.

And even in cities and towns that do host public access stations, the franchise payment they receive may go to other municipal priorities. Making matters worse, Buske said, the timing of this law—at the beginning of the Great Recession—meant that cash-strapped cities often “needed that 5 percent to plow the streets.” Public access budgets were slashed or gutted entirely.

That leaves the 1 percent provision for funds to support PEG. According to federal law, however, “[a] local entity may, by ordinance, establish a fee to support PEG channel facilities.” Key words: “may” and “facilities.” Under DIVCA, the PEG money that comes from that 1 percent of gross cable revenue is restricted to use on facilities only. As a result, many public access centers can afford to rent studios, but not to hire the staff needed to operate them.

“The state governments and the legislatures gave the cable operators a free pat. There’s very little oversight of the operation of the cable company.”

In California, the negative impact of DIVCA on public access television was almost immediate. At least 51 stations closed down since the law went into effect, mostly around San Francisco and L.A. freed of the responsibility to provide those stations with support, the full revenue from those markets now stays with the cable provider. While 1 to 6 percent in additional revenue doesn’t sound like a lot, those small amount do add up.

“It’s not an inconsequential amount of money,” Wassenar said. “If you figure that franchise fees are capped at 5 percent of gross franchise money and let’s say there’s 10,000 subscribers and the average subscriber pays $70 a month. So that’s $700,000 a month times 12: it’s now $8.4 million. Five percent of that would be what, about $400,000?”

Take that 400,000 and multiply it times 51, and it’s more than $20 million a year. And that’s only if each town had just 10,000 subscribers, which is a pretty conservative estimate for medium-sized suburbs of two of the largest metropolitan areas in the country.

So sure, the cable companies no longer control the individual markets outright, but AT&T just cut its expenses by upwards of $20 million a year. That’s enough to air one of those ads where the company brags about how much they save you when you switch.

And while, in theory, this new competition should have driven cable bills down; in practice, the average cable bill in California, like the average cable bill in every other state, has only increased. In effect, it has meant customers are getting fewer services at a higher price.

“There’s been no drop in consumer prices, which is actually one of the great claims, ‘We get local governments out of the way and they’ll go down,’” Wassenar said. “That hasn’t been the case. Prices have been raising consistently by about nine percent each year regardless of the economy, and that’s been driven by profit-seeking by channel providers.”

State-wide franchising laws like DIVCA have now passed in 27 states, leading to the closure of “at least hundreds” of public access centers. How many public access stations have shut downs is hard to tabulate, as the total number of centers in the United States is a trade secret among cable companies and not shared with the public.

According to Wassenar, DIVCA and laws like it are easily the biggest current threat to the medium. Laws like DIVCA, he explained, make it harder for stations to secure funding, which was already perilously scarce when the economic downturn hit. Making matters worse, Wassenar adds, is the way technology has outpaced available funding. Even New York City’s MNN—one of the most secure and well-funded stations in the country—only started offering its first HD channel in March 2016, after years of negotiation and fundraising.

“It’s a combination of unfavorable public policy, plus pressure on local government, plus rapid technological and audience change—those are really the main challenges we face,” Wassenar said. “So we need to be able to find ways to solve the first two so that we can respond to the last one.”

One of the possible solutions being pursued is legislation at the federal level. According to Buske, “All it’d take would be one or two words in the Cable Act,” to end the restriction on PEG money and create some more protections for public access providers.

So far, the only concrete action taken has been in the form of the Community Access Preservation Act. The proposed law would amend the Communications Act to end PEG restrictions and have cable companies pay for the cost of improving signal quality. The bill was last introduced by Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin in May of 2015 but remains stalled in committee. Govtrack.us, a site that monitors acts of Congress, reports that the bill has only an 8 percent chance of moving to the full Senate and no more than 4 percent chance of passage.

While advocates like Buske and Wassenar still see the bill as the best shot at preserving community media, others who believe in the democratic spirit of public access favor finding new ways to make the tools of mass media more widely available.

On a regular Monday evening, the fourth floor workshop that houses ITP at NYU is busy. Two guys having a lively conversation about programming brush past me, shouting something vague and jargony about “design.” Grad students and professors work in tandem on Rube Goldberg-looking machines or toy intensely with microchips. The whole place feels very Wonka-esque—just with cameras and computer guts instead of sweets.

If public access television is the endearingly amateurish, homespun vision of participatory media, then the ITP is its sleeker, more modern cousin. It’s no wonder, then, that both owe much of their origins to the same woman: Red Burns.

Burns laid the groundwork for turning her Alternate Media Center into ITP in 1979, when she convinced Time Warner to run an additional wire from their cable network to an NYU facility. This gave Burns and her students air time on the same cable system that public access used. However, thanks to her first-hand understanding of the limitations of public access, Burns would would go on to use this resource to much different ends.

The goal this time around was to have a slightly higher degree of control and put things in the hands of professionals. The unwashed masses could still interact, but the professionals were there to keep it all on the rails. O’Sullivan said himself that “it wasn’t very interactive,” in those early days.

The Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU.

At first, ITP worked on connecting the different networks, which, at the time, were just TV and phone. This was where O’Sullivan got his start with NYU. He worked with Burns as a student, creating shows like “Dan’s Apartment,” an interactive experiment that allowed viewers to tour his tiny studio using the touch-tone dial pads on their phones. This would cycle them through a series of static shots he had taken with a video camera.

Since the most recent technological revolution has turned everyone and his brother into a videographer, O’Sullivan predicts that the future of interactive media is going to be about bridging the technical gap between regular people and the tools of mass media. To do so, he proposes making the the more costly elements of filmmaking—elaborate sets, visual effects, rich sound details—more readily available and interchangeable.

“When you shoot a film, you shoot it in whole cloth, you don’t shoot it in bits,” O’Sullivan said. “You can’t rearrange it. We’re trying to change that.” His vision of community media is one of a global community coming together to tell stories using each other’s ‘elements.’”

A guy in Ontario, for example, might use a computer-generated background made by a tech wiz in Bloomington or a song written by a musician in Tuscaloosa as details in his short film. In other words, he hopes to give people the freedom to make things without the burden of technical know-how.

While O’Sullivan said that public access television will still likely continue to have a place in this world, it may not look like it does now and it will never match the internet in reach.

Public access die-hards, like Suzanne St. John-Crane of San Jose’s CreaTV, still believe in the current conventions of public access TV. Her station opened in 2007 out of the ashes of San Jose’s previous public access station, which closed in DIVCA’s wake. Since their federal PEG money is restricted to use on facilities, the new station has had no choice but to cover the majority of its budget—which in 2016 is projected at just under $2 million—on its own.

The public access studio at CreaTV in San Jose.

“There are those of us in public access that have seen the writing on the wall and have been forced to take a look at the model and evolve,” St. John-Crane said. “I think that’s the key word here: evolve. And many of us are.”

That evolution, she added, doesn’t often take the form of high-tech solutions. Instead, it simply means finding creative ways to raise money, the chief among them simply proving to their communities that they are worth the investment. This has led to initiatives by CreaTV San Jose that run the gamut from media education programs in local schools to offering their services to the local government. While some experiments have had more success than others, St. John-Crane says they have given her and CreaTV a previously unheard of level of autonomy and self-reliance.

“We’re kind of like ‘Wayne’s World’ on steroids.”

Despite the success of these newer methods, St. John-Crane still believes the thing that may ultimately prove to be public access television’s saving grace is simply the fact that there’s nothing quite like it out there. While trying to explain what public access does to someone from IDEO, a prestigious California design firm, St. John-Crane came to the realization that the public access “brand” may be more popular than she originally thought.

“I told him, ‘We’re kind of like ‘Wayne’s World’ on steroids,’” St. John-Crane said. “And [the designer] said ‘Don’t discount that—that’s DIY, that’s big right now.’ And sure enough a couple years later you have Zach Galifianakis doing ‘Between Two Ferns,’ with the President, which is a total public access rip off, and you have Stephen Colbert going to a public access station in Michigan.”

That DIY aesthetic certainly also helped Chris Gethard, whose show is in its second season after making the jump from public access to the cable network Fusion. The ability to move up the commercial ladder was due in part to its under-produced, public access style. Call it what you will—amateurish, wildly unpredictable, or so-bad-it’s-good—it has its charms.

Ultimately, St. John-Crane believes that unusual appeal has contributed to a revival in the format, which she hopes will sustain it for at least a few more years.

“I think it’s having a Renaissance right now and as someone who has been working in community TV for 20 years, it’s very interesting,” St. John-Crane said. “I think if we play our cards right and our Congress people pay attention, we could be making some very exciting things.”

The studio at Manhattan Neighborhood Network.

I first walked into the television studios at the Manhattan Neighborhood Network on 59th Street in late April of 2014 to watch “The Chris Gethard Show.” This staple of the late-night comedy scene, attended that night by about 50 other people—mostly regulars, many in costume—was a New York City cult favorite, known for its adventures in experimental, participatory broadcasting. Under the direction of its eponymous host, past episodes have featured everything from a presidential debate with the Rent is Too Damn High Party’s Jimmy McMillan to the concoction and consumption of a milkshake made of whatever callers asked the hosts to throw into a blender.

Gethard’s show could only really happen at a place like MNN, which, as a public access station, gives airtime to anyone with an address ending in a Manhattan zip code. While the station’s programming does not always take the form of underground comedy or vomit-inducing smoothies, the basic idea behind public access is to facilitate whatever community producers decide to present. Whatever, in this case, includes things like the challenge-based art show “Let’s Paint TV,” in which the host John Kilduff takes calls and paints pictures while running on a treadmill, or the X-rated MNN party show, “SubZero TV,” which features hip-hop performances interspliced with gratuitously pornographic dance sequences. Above all else, says Alliance for Community Media president Mike Wassenar, public access is a platform where all comers gets to say and do what they want.

The Chris Gethard Show.

This directive has been in place since the launch of public access television more than 40 years ago. It puts the same tools the dominant mass media outlets use into the hands of people whose voices “real TV” normally excludes. “We may be living in a golden age of quality television,” said Wassenar. “But it’s not television that necessarily describes my world or your world or your needs.”

Public access is meant to address those needs, which would otherwise be ignored. As a result, local public access programming tends to reflect the community it serves. Middle-American public access stations, for example, “tend to have polka” shows, Wassenar said, simply because they would likely never been aired in media centers like Los Angeles and New York City.

Advocates like Wassenar, however, maintain that public access still serves the public good. He holds out hope that the challenges the medium faces will ultimately prove to be nothing more than growing pains that will help it evolve for the better.But, after decades of shows like Gethard’s—along with programming that range from the political and educational to spiritual and cultural—public access is facing some difficult questions about its future. Local governments have been slashing the budgets of public access television station and cable providers have lobbied hard for new legislation that would free them of their obligation to fund these shoestring operations. Some have argued that developments like the Internet might render public access television obsolete. Even the late Red Burns, who many consider the godmother of public access, eventually came to dismiss it derisively as nothing more than “vanity video,” as one of her protégés Dan O’Sullivan, recalled her saying.

“We may be living in a golden age of quality television,” said Wassenar. “But it’s not television that necessarily describes my world or your world or your needs.”

To grapple with these questions—and to understand what’s at stake, how public access is being threatened, and how serious that threat is—we need to examine the medium’s origins and purpose. But, before all that, let’s look at what happens when the tools of mass media are handed to everyday people.

Gethard’s show, which relies heavily on input from the in-studio audience, from callers, and from a live chatroom where viewers comment in real-time, is as good an example as any of what can happen when amateurs seize the airwaves.

True to form, the show was a chaotic mess that night two years ago. As soon as the cameras turned on, for no apparent reason, the audience began bellowing a chant “Eat more butts,” much to Gethard’s delight.

After about 10 minutes, the musical guest, a Brooklyn-based punk rocker named Jeff Rosenstock started playing a song that incorporated the audience’s pro-analingus message, prompting people to get up on their feet and yell the same chant even louder. When the crowd finally settled, Gethard offered only a meek, “Sometimes that’s how our show begins,” before beginning his planned intro. By then, he was 16 minutes into the hour-long program.

From there, the show fell back into its regular format, which consists of Gethard and his panel of fellow comedians fielding calls on some topic; this night, anxiety. One regular caller, known only as “Sudo,” used his airtime to make unintelligible noises while the panelists wondered aloud what he wanted from them. Minutes later, another caller named Paige called in to voice some of her fears and ask the panelists for life advice. Between the phone calls and the chanting and periodic check-ins with the chat room, the audience steered the show more than the host, which, yes, meant the whole thing ran into the rocks more than once.

The studio’s four HD cameras—operated by a volunteer staff made up mostly of art school students and other local comedians—captured the anarchic display. This debauched signal was sent to the sound booth down the hall and then relayed almost instantaneously through the same set of cables that Time Warner uses to deliver all its content to homes throughout Manhattan.

While it could be argued that “The Chris Gethard Show” meets the criteria of Burns’ “vanity video,” even the most skeptical viewer would find it hard to deny that there is something inherently exciting about amateurs making television. It is a bit like giving lit fireworks to a dog. It probably will go horribly, horribly wrong, but, when it succeeds in making something watchable, it’s that much more engaging because of how miraculous it is.

More importantly, “The Chris Gethard Show” parallels the spirit of what public access as a whole is meant to support: an open platform for the likes of Gethard, Paige, “Sudo,” and the studio audience. A place for everyone.

In his book, Public Radio and Television in America, Ralph Englemen describes the creation of public access television as “a historical accident,” that was, “the result of the confluence of social and technological development that spawned strategic if transitory alliances.” To put it in a way that the architects of public access might have preferred, public access was and is an experiment.

In 1970, a cadre of advocates capitalized on widespread public frustration over the closed-door negotiations then underway to establish a cable franchise in Manhattan. They pressured the Teleprompter Corporation cable company into making a last minute addition to its 20-year franchise contract for the borough. Teleprompter’s president at the time, Irving Khan, promised in this agreement that the company would “open our [two] public channels at no charge.” He promised to reserve them for noncommercial programming that any New Yorker could produce at the service provider’s expense.

The founding principle behind the agreement is that the airwaves—literally the spectrum of electromagnetic frequencies capable of carrying broadcast signals—are too precious and too scarce for any one company to own. They are, by default, a public good. To take advantage of this resource, the advocates argued, the television companies needed to give its owners—the public—some form of compensation, or rent.

So, a little more than a year later, in July of 1971, the first two public access stations opened for business, giving the people of New York City newfound access to this precious, unique resource.

Among those best positioned to take advantage of the deal were Burns and George Stoney, two filmmaker-educators who’d been involved with earlier participatory filmmaking experiments in Canada. Through the video group they co-founded, the Alternate Media Center at New York University, they brought together a team of documentarians and other filmmakers to generate interactive and community programming.

While their media center would eventually shift away from public access when it evolved into NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program, O’Sullivan, the current ITP chair, said the program’s founders saw the start of amateur TV as a media revolution waiting to happen.

In 1967, Sony debuted its Portapak video camera, a camcorder precursor that was among the first consumer-grade portable cameras. When Burns saw this, O’Sullivan said, she realized video was going to change everything; “That’s going to change who can tell what stories.”

Red Burns with a Protapak camera.

Using this revolutionary technology, members of the collectives that operated out of the center went all around the city to gather some of those new stories. In an era still dominated by the four major networks, these community media pioneers distinguished themselves by concentrating on what the evening news ignored: small stories that mattered to everyday New Yorkers.

One early video made by Burns and her students, for example, was an hour-long documentary about a neighborhood in need of a new stop light. Using one of those revolutionary Portapacks, the students recorded the flow of traffic at the intersection and interviewed residents. When they’d finished the film, they showed the tape to city officials, who then acquiesced to the neighborhood’s requests. “This was really empowering and really convinced me that this had a lot of legs,” Burns said in an interview before her death in 2013.

These student collectives, along with three others founded by the New York State Council on the Arts—the Global Village, the Radiance Corporation and People’s Video Theater— were soon producing 200 hours of television a week for the two public access channels. All of these groups drew heavily on the successes and failures of earlier forays into the medium, some from professionally produced public television networks in the United States and Canada.

In March, 1972, the Federal Communications Commission issued its Cable Television Report and Order. Using the Teleprompter deal as a model, it mandated that all cable systems operating in markets with 3,500 or more subscribers establish noncommercial access stations for public, educational and governmental access.

Included in this mandate was the FCC’s assertion of regulatory control over cable. This, the commission believed, could be used to turn cable—partially through public access—into a medium that could facilitate “local expression,” “diversity,” “a sense of community to cable subscribers,” and “the functioning of democratic institutions.” The intention, in other words, was to create the 20th century version of the town square—a mass media-driven venue where ordinary people could gather for the exchange of ideas.

Public access advocates, like Burns and Stoney, saw this function as a vital contribution to modern, electrified society. O’Sullivan said at its best, public access mitigates some of the undesirable effects of mass communication. “Until television and film came along, media was pretty symmetrical,” O’Sullivan said, adding that media such as books, newspapers, and magazine, provided for a one-to-one relationship between creator and consumer. With the advent of film and television, the relationship became one-to-many, and limited access to the tools of media to the few. This is a problem, O’Sullivan said, because “the more democratically available the means of expression are, the healthier our society will be.”

The success of these early experiments encouraged more public access stations to crop up all over the country. Burns’ Alternate Media Center sent interns and apprentices to places like Bloomington, Indiana; Concord, New Hampshire; and Reading, Pennsylvania, and trained local facilitators. Even cable companies—eager to appeal to customers in markets where they had yet to gain a foothold—got in on the bonanza as a public relations tool. They provided the promise of public access as an incentive to get city and towns to sign onto their service.

“The more democratically available the means of expression are, the healthier our society will be.”

Durings the 1970s and 1980s, the relationship between local governments, public access centers, and cable companies evolved into what we know it as today. With a few exceptions until recently, each city or town managed its own community access outlet.

The funding that cable companies provided to public access stations comes from a “franchise fee,” or a fee levied by the municipality in exchange for having allowed the local cable franchise to operate. This fee is usually set at about five percent of the cable company’s total gross revenue from the town’s subscribers. The federal government also compelled cable companies to provide special funding directly to stations at a rate of about one percent of the cable company’s gross revenue in that local market. This one percent is known as Public, Educational, and Governmental funding—or PEG for short—and is restricted for use on “capital costs,” such as equipment and rental fees for studio space.

In 1992, Congress passed another Cable Act, clarifying earlier laws and making franchise fee money fungible, thus allowing local governments to spend it any way they chose. In times when local governments were strapped for cash, this meant that they could raid the public access stations for money to use on infrastructure, education, or anything else a city pays for.

Even still, for the next few years, public access television plugged along. From its origins in experimental video collectives in New York City, the medium soon entered the larger pop culture lexicon through movies like “Wayne’s World” and early MTV shows like “Squirt TV,” which originally ran on MNN and imitated the kitschiness of public access. A brief heyday in the 1980s and 1990s gave way to a whole new set of challenges as new companies entered the cable business.

With few exceptions, cable franchises have traditionally been negotiated on a local level, a direct result of how the cable industry developed. In the 1970s and 1980s, as cable lines and infrastructure stretched their way slowly from the cities to the hinterlands, each new municipal client got its own deal with a cable company. As a result, funding allocated for public access television varied from locale to locale. The more the town or city wanted a public access outlet, the more funding they would allocate to it in the deal.

Some states began to revise that model in the early 2000s, as telecom companies, particularly AT&T, attempted to expand in states like California. But the patchwork, town-by-town approach proved too costly and unwieldy. Instead, AT&T proposed a statewide model In California, this took the form of the Digital Infrastructure and Video Competition Act, known as DIVCA, which framed the argument for statewide franchising as a way to “encourage competition.” Before then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signed DIVCA into law late in 2006, cable providers in California enjoyed exclusive domain over every town they served. The telecom companies contended that the arrangement constituted monopoly control. As an argument was a pretty easy sell. People love the free market almost as much as they hate their cable provider.

But, just to make sure things went as smoothly as possible, AT&T also spent $23 million on pro-DIVCA ads and political donations in the state of California in 2006. The bill’s sponsor—then-speaker Fabian Nuñez—was among the beneficiaries, collecting nearly $80,000 in direct donations from AT&T in 2005 and 2006. There were even accusations that Nuñez reaped indirect financial benefits for his support.

While Nuñez maintains his sponsorship of the bill grew out of his belief that it would drive healthy competition, several watchdog groups questioned his motives. After term limits forced him out of the statehouse in 2008, Nuñez accepted a job at Mercury Public Affairs, which did little to quell speculation, as client rolodex of the California-based consulting firm includes AT&T.

Even the big, bad cable companies like Time Warner and Comcast, which originally withheld their support for the measure, eventually became DIVCA proponents, even though it would cause them to lose control over local markets. This change of heart happened once the bill reached the State Senate, where lawmakers revised the bill, granting cable companies the same right to negotiate on a statewide level that was being proposed for the telecom companies. In other words, the right to negotiate on a statewide level is of greater value than a virtual monopoly over local markets. With this kind of support, the bill passed unanimously in the State Assembly and 33-4 in the State Senate.

The new law took effect in 2007 and also relaxed many of the earlier regulations, including those surrounding public access funding from cable companies. DIVCA did not eliminate, but loosened the need to pay local governments hundreds of thousands, even millions, of dollars to rent the airwaves from the people. As the San Francisco-based lobbyist Sue Buske said, “The only rent that goes back from the cable company to the local government is something called the franchise fee, and that’s capped by the federal government.”

Local governments, she said, have lost the right to negotiate for anything more. “In a lot of the states that this happened,” Buske said. “The state governments and the legislatures gave the cable operators a free pat. There’s very little oversight of the operation of the cable company.”

Sue Buske, media consultant and President of the Buske Group.

The cap on the franchise fee is 5 percent. This means that up to 5 percent of the provider’s gross revenue from customers in a given city goes back to that city’s government. In addition, DIVCA allows local entities to request PEG support of 1 percent of the holder’s gross revenues. So, in principle, as much as 6 percent of gross cable revenue could be given to access centers, although in practice, it rarely ends up being that much.

First off, cities and towns don’t always get the full 5 percent franchise fee. This is especially true in places where the cable providers make the franchise fees a line-item on monthly cable bills. That means the customer is often charged for a service that should be the company’s responsibility. The line item fee may even appear on the bills of customers whose cities don’t even operate public access stations.

And even in cities and towns that do host public access stations, the franchise payment they receive may go to other municipal priorities. Making matters worse, Buske said, the timing of this law—at the beginning of the Great Recession—meant that cash-strapped cities often “needed that 5 percent to plow the streets.” Public access budgets were slashed or gutted entirely.

That leaves the 1 percent provision for funds to support PEG. According to federal law, however, “[a] local entity may, by ordinance, establish a fee to support PEG channel facilities.” Key words: “may” and “facilities.” Under DIVCA, the PEG money that comes from that 1 percent of gross cable revenue is restricted to use on facilities only. As a result, many public access centers can afford to rent studios, but not to hire the staff needed to operate them.

“The state governments and the legislatures gave the cable operators a free pat. There’s very little oversight of the operation of the cable company.”

In California, the negative impact of DIVCA on public access television was almost immediate. At least 51 stations closed down since the law went into effect, mostly around San Francisco and L.A. freed of the responsibility to provide those stations with support, the full revenue from those markets now stays with the cable provider. While 1 to 6 percent in additional revenue doesn’t sound like a lot, those small amount do add up.

“It’s not an inconsequential amount of money,” Wassenar said. “If you figure that franchise fees are capped at 5 percent of gross franchise money and let’s say there’s 10,000 subscribers and the average subscriber pays $70 a month. So that’s $700,000 a month times 12: it’s now $8.4 million. Five percent of that would be what, about $400,000?”

Take that 400,000 and multiply it times 51, and it’s more than $20 million a year. And that’s only if each town had just 10,000 subscribers, which is a pretty conservative estimate for medium-sized suburbs of two of the largest metropolitan areas in the country.

So sure, the cable companies no longer control the individual markets outright, but AT&T just cut its expenses by upwards of $20 million a year. That’s enough to air one of those ads where the company brags about how much they save you when you switch.

And while, in theory, this new competition should have driven cable bills down; in practice, the average cable bill in California, like the average cable bill in every other state, has only increased. In effect, it has meant customers are getting fewer services at a higher price.

“There’s been no drop in consumer prices, which is actually one of the great claims, ‘We get local governments out of the way and they’ll go down,’” Wassenar said. “That hasn’t been the case. Prices have been raising consistently by about nine percent each year regardless of the economy, and that’s been driven by profit-seeking by channel providers.”

State-wide franchising laws like DIVCA have now passed in 27 states, leading to the closure of “at least hundreds” of public access centers. How many public access stations have shut downs is hard to tabulate, as the total number of centers in the United States is a trade secret among cable companies and not shared with the public.

According to Wassenar, DIVCA and laws like it are easily the biggest current threat to the medium. Laws like DIVCA, he explained, make it harder for stations to secure funding, which was already perilously scarce when the economic downturn hit. Making matters worse, Wassenar adds, is the way technology has outpaced available funding. Even New York City’s MNN—one of the most secure and well-funded stations in the country—only started offering its first HD channel in March 2016, after years of negotiation and fundraising.

“It’s a combination of unfavorable public policy, plus pressure on local government, plus rapid technological and audience change—those are really the main challenges we face,” Wassenar said. “So we need to be able to find ways to solve the first two so that we can respond to the last one.”

One of the possible solutions being pursued is legislation at the federal level. According to Buske, “All it’d take would be one or two words in the Cable Act,” to end the restriction on PEG money and create some more protections for public access providers.

So far, the only concrete action taken has been in the form of the Community Access Preservation Act. The proposed law would amend the Communications Act to end PEG restrictions and have cable companies pay for the cost of improving signal quality. The bill was last introduced by Democratic Senator Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin in May of 2015 but remains stalled in committee. Govtrack.us, a site that monitors acts of Congress, reports that the bill has only an 8 percent chance of moving to the full Senate and no more than 4 percent chance of passage.

While advocates like Buske and Wassenar still see the bill as the best shot at preserving community media, others who believe in the democratic spirit of public access favor finding new ways to make the tools of mass media more widely available.

On a regular Monday evening, the fourth floor workshop that houses ITP at NYU is busy. Two guys having a lively conversation about programming brush past me, shouting something vague and jargony about “design.” Grad students and professors work in tandem on Rube Goldberg-looking machines or toy intensely with microchips. The whole place feels very Wonka-esque—just with cameras and computer guts instead of sweets.

If public access television is the endearingly amateurish, homespun vision of participatory media, then the ITP is its sleeker, more modern cousin. It’s no wonder, then, that both owe much of their origins to the same woman: Red Burns.

Burns laid the groundwork for turning her Alternate Media Center into ITP in 1979, when she convinced Time Warner to run an additional wire from their cable network to an NYU facility. This gave Burns and her students air time on the same cable system that public access used. However, thanks to her first-hand understanding of the limitations of public access, Burns would would go on to use this resource to much different ends.

The goal this time around was to have a slightly higher degree of control and put things in the hands of professionals. The unwashed masses could still interact, but the professionals were there to keep it all on the rails. O’Sullivan said himself that “it wasn’t very interactive,” in those early days.

The Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU.

At first, ITP worked on connecting the different networks, which, at the time, were just TV and phone. This was where O’Sullivan got his start with NYU. He worked with Burns as a student, creating shows like “Dan’s Apartment,” an interactive experiment that allowed viewers to tour his tiny studio using the touch-tone dial pads on their phones. This would cycle them through a series of static shots he had taken with a video camera.

Since the most recent technological revolution has turned everyone and his brother into a videographer, O’Sullivan predicts that the future of interactive media is going to be about bridging the technical gap between regular people and the tools of mass media. To do so, he proposes making the the more costly elements of filmmaking—elaborate sets, visual effects, rich sound details—more readily available and interchangeable.

“When you shoot a film, you shoot it in whole cloth, you don’t shoot it in bits,” O’Sullivan said. “You can’t rearrange it. We’re trying to change that.” His vision of community media is one of a global community coming together to tell stories using each other’s ‘elements.’”

A guy in Ontario, for example, might use a computer-generated background made by a tech wiz in Bloomington or a song written by a musician in Tuscaloosa as details in his short film. In other words, he hopes to give people the freedom to make things without the burden of technical know-how.

While O’Sullivan said that public access television will still likely continue to have a place in this world, it may not look like it does now and it will never match the internet in reach.

Public access die-hards, like Suzanne St. John-Crane of San Jose’s CreaTV, still believe in the current conventions of public access TV. Her station opened in 2007 out of the ashes of San Jose’s previous public access station, which closed in DIVCA’s wake. Since their federal PEG money is restricted to use on facilities, the new station has had no choice but to cover the majority of its budget—which in 2016 is projected at just under $2 million—on its own.

The public access studio at CreaTV in San Jose.

“There are those of us in public access that have seen the writing on the wall and have been forced to take a look at the model and evolve,” St. John-Crane said. “I think that’s the key word here: evolve. And many of us are.”

That evolution, she added, doesn’t often take the form of high-tech solutions. Instead, it simply means finding creative ways to raise money, the chief among them simply proving to their communities that they are worth the investment. This has led to initiatives by CreaTV San Jose that run the gamut from media education programs in local schools to offering their services to the local government. While some experiments have had more success than others, St. John-Crane says they have given her and CreaTV a previously unheard of level of autonomy and self-reliance.

“We’re kind of like ‘Wayne’s World’ on steroids.”

Despite the success of these newer methods, St. John-Crane still believes the thing that may ultimately prove to be public access television’s saving grace is simply the fact that there’s nothing quite like it out there. While trying to explain what public access does to someone from IDEO, a prestigious California design firm, St. John-Crane came to the realization that the public access “brand” may be more popular than she originally thought.

“I told him, ‘We’re kind of like ‘Wayne’s World’ on steroids,’” St. John-Crane said. “And [the designer] said ‘Don’t discount that—that’s DIY, that’s big right now.’ And sure enough a couple years later you have Zach Galifianakis doing ‘Between Two Ferns,’ with the President, which is a total public access rip off, and you have Stephen Colbert going to a public access station in Michigan.”

That DIY aesthetic certainly also helped Chris Gethard, whose show is in its second season after making the jump from public access to the cable network Fusion. The ability to move up the commercial ladder was due in part to its under-produced, public access style. Call it what you will—amateurish, wildly unpredictable, or so-bad-it’s-good—it has its charms.

Ultimately, St. John-Crane believes that unusual appeal has contributed to a revival in the format, which she hopes will sustain it for at least a few more years.

“I think it’s having a Renaissance right now and as someone who has been working in community TV for 20 years, it’s very interesting,” St. John-Crane said. “I think if we play our cards right and our Congress people pay attention, we could be making some very exciting things.”