The Prison Pipeline

Human traffickers recruiting from among female jail populations to add to their underground crime rings

by Larson Binzer

Aubree Alles looks like any other overworked 36-year-old. Between going back to school, staying involved in her local church, and raising her ten-year-old daughter, she functions on very little sleep and refers to her driver seat of her 2007 Dodge Ram as a second home, office, and call center. No one would ever guess that it has been only five years since the busy mom from Orlando narrowly escaped a life of rape, drugs, and violence.

While serving time for drug possession in 2001, Alles, who was 20 at the time, bonded with her pregnant bunkmate, Rawz, over their shared love of children and history of substance abuse. Both were released at about the same time and Rawz offered Alles room and board in exchange for help around the house and Alles gratefully agreed.

Over the next several months, Alles would not be the woman’s only young houseguest, as many homeless teenagers settled into the apparent haven. From household chores, Rawz promoted Alles to the role of chauffeur and instructed her to drive their housemates to different locations around Orlando, wait outside, and then escort the disheveled women home a half hour later. Alles buried her disgust, thankful for shelter and the consistent supply of the drugs her housemother made available. But when on one of these outings, the girl’s client decided he wanted Alles instead, she joined those who were being regularly being ushered in and out of back doors and motel rooms. Rawz threatened her with eviction or beatings if she did not cooperate.

Alles standing outside an abandoned hotel, where she once lived for several months with her trafficker in room 21

So Alles quickly developed a steady clientele and lived a life coerced into commercial sex at the hands of Rawz and her associates. In that time, Alles amassed a record of 23 criminal convictions for petty crimes and prostitution. And yet in almost two dozen stints in various jails and prisons around central Florida, no one ever thought to ask about what actually had caused her to join the ranks of 49,000 to 56,000 women arrested on prostitution charges annually.

Traffickers, it turns out, have identified the prison system as fertile recruitment territory for their “stables.” Female prison facilities are filled with women serving out sentences for prostitution but who, in fact, are unrecognized victims of human trafficking. They’ve been brought into the life in one of two ways: through manipulators on the inside, like Rawz, who promise their prisonmates stability and employment once they both are released. Or, from the outside, traffickers will seek out young or naive inmates through public records that they sense will be vulnerable to exploitation. The correspondence they initiate leads to similar offers.

Another of the hotels in Orlando where Alles was trafficked

Only recently have prison systems begun to realize how much their correctional officers need to be trained to recognize the signs of trafficking in their midst. For the most part, prison staff are not keyed to spot signs of trafficking among women inmates, or how to look for indicators of recruitment among inmates under their supervision. Although a handful of states have begun to implement training programs to raise the level of awareness in their institutions, most correctional departments have no human trafficking training program at all, and, when asked, had no awareness that prison recruitment is an issue.

In her 23rd prison stint, Alles was finally asked how she had ended up in jail, but not by a correctional officer. Rather, she was approached by a chaplain making rounds who was willing to listen to Alles’ history. The chaplain pieced together that there may have been a more complex tale behind Alles’ prostitution charges. The woman eventually led Alles to a nonprofit organization, Samaritan’s Village, that helped her leave the abusive life with Rawz behind her. None of this assistance came to Alles from the system that incarcerated her.

Alles sorting through donations to the safe house she is working to refurbish, March 2016

In redefining her life, Alles is opening a safe house for other victims of human trafficking where they can come to heal and get help. The Love Church in Orlando has provided her with a three-bedroom refuge for the women and administrative assistance.

“Victoria just called me and said ‘it’s time,’” Alles said of the leader of the church. “She said I’d have to fix it up myself, that it would be hard, but that if I was willing to do it, I could have the house for free to take care of the girls.”

We drove north along the trail — Floridians call it the “OBT,” a road that stretches 433 miles vertically across the state — before Alles abruptly slammed on the brakes to make a quick U-turn. “I remember her!” she cried out, gesturing to a woman on a street corner who was leaning against a white Mustang at a stop sign. “We used to work out here together.” This was one of the streets Alles’ trafficker used to put her out on.

We drove north along the trail — Floridians call it the “OBT,” a road that stretches 433 miles vertically across the state — before Alles abruptly slammed on the brakes to make a quick U-turn. “I remember her!” she cried out, gesturing to a woman on a street corner who was leaning against a white Mustang at a stop sign. “We used to work out here together.” This was one of the streets Alles’ trafficker used to put her out on.

Alles pointed to the darkened enclaves of Orange Blossom Trail as she drove down the street.“It got to the point around here,” she said, “where if a man told a cab driver to ‘take him to the girls,’ the cabbie would know exactly where to go here,” She switched the pop music that was playing on her car radio to the gospel station.

Another hotel where Alles was trafficked along Orange Blossom Trail

After the Mustang pulled away, Alles pulled up alongside the street and called out to the woman—Diane— over and away from a lanky man half perched on a bicycle. Diane was a short black woman with a kind smile and a full bosom that was escaping her white camisole. Her shoulder length hair needed a wash. “Big Baby! Is that you?” Diane yelled, hastening toward the car as soon as she recognized Alles, despite a limp in her right leg. Diane wasn’t one of Rawz’s girls, but she and Alles worked the same area for five years.

The two caught up for several minutes, discussing jobs, mutual friends, and their children.

Finally, Alles offered the woman “hygiene,” handing over a small zip lock filled with sample sized soaps and a hot pink loofa. Alles kept these toiletry bags premade in her car to give to women on the street, as traffickers often don’t provide basic cleaning materials. “Even if they don’t have their own bathroom, at least they can go into a public bathroom and take care of themselves a little bit, to feel like a person again,” Alles would say later.

To Diane, she said, “If you ever want to get out of the life, you give me a call.You don’t have to be ready, you just call me and we’ll do it together.” They exchanged numbers and hugged, and Alles glanced over at the man on the bicycle, who had carefully watched the encounter. “Tell Money to be good,” Alles said before quickly pulling away from Diane’s work corner.

Behind Alles’ truck, Money climbed onto his bike and followed us, pulling up to the driver’s side while we waited to make the turn back onto OBT northbound. “Big Baby?” he said through the half-open window, only his tattered Florida State shirt visible to me in the passenger seat. “Nice wheels. You must be doing good for yourself.” He smiled and pushed his arm into the car to touch Alles’ shoulder. “I love you,” he finished as the road opened up for us to merge.

Alles shivered and let out a disgusted sound as he peddled away. “I haven’t seen him in five years,” she said, explaining that Money was Rawz’s doorman, and someone everyone knew but no one messed with. “He used to stand guard outside the door while she beat me for hours so no one could come in.”

He used to stand guard outside the door while she beat me for hours so no one could come in.”

Money was also the man who intercepted Alles the first time she tried to escape, the failed attempt that led to one six-hour beating. It was this experience that strengthened her determination to escape, even if it cost her her life.

Alles explained that the absence of a pimp or trafficker in the vicinity of a woman selling sex does not mean she is doing so of her own volition. “Ninety percent of the time, women choosing prostitution as their means of supporting themselves are not going to be out here on the street corner,” Alles said. “They’re going to be on backpage or the ‘high class’ ways of finding work.” For the trafficked, the situation is different. “If you’ve got threats against your life, or are hooked on drugs,” she said, “you’re going to do what you have to do.”

Alles explained that the absence of a pimp or trafficker in the vicinity of a woman selling sex does not mean she is doing so of her own volition. “Ninety percent of the time, women choosing prostitution as their means of supporting themselves are not going to be out here on the street corner,” Alles said. “They’re going to be on backpage or the ‘high class’ ways of finding work.” For the trafficked, the situation is different. “If you’ve got threats against your life, or are hooked on drugs,” she said, “you’re going to do what you have to do.”

Human trafficking experts explain that victims are given a daily quota to meet, usually between $500-$1,000, Alles said. They are told that if they come back with less, they will be beaten, starved, or deprived of drugs. Traffickers will also convince the women of their love for them. They may assure them of posting bail in the event of an arrest but then threaten to revoke it if the woman misbehaves. They create a vicious cycle of loyalty and debt that will not be forgiven.

For the past six years, John Meekins* has been studying the jailhouse recruitment of women into human trafficking rings. As correctional officer at the Lowell Correctional Institution in central Florida, he happened to attend a seminar conducted by the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators back in 2010. This voluntary training was the first instruction on sex trafficking that he ever received. It made him think back to earlier parts of his career and the obvious signs of trafficking and abuse that he had missed. This prompted him to begin a “low key” anti-trafficking campaign in his prison by putting up posters that defined human trafficking and provided information about how to report it to prison authorities. The administration has allowed his self-styled campaign but has not officially endorsed it.

For the past six years, John Meekins* has been studying the jailhouse recruitment of women into human trafficking rings. As correctional officer at the Lowell Correctional Institution in central Florida, he happened to attend a seminar conducted by the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators back in 2010. This voluntary training was the first instruction on sex trafficking that he ever received. It made him think back to earlier parts of his career and the obvious signs of trafficking and abuse that he had missed. This prompted him to begin a “low key” anti-trafficking campaign in his prison by putting up posters that defined human trafficking and provided information about how to report it to prison authorities. The administration has allowed his self-styled campaign but has not officially endorsed it.

Several weeks after he began his efforts, an offender approached Meekins and told him that she had been charged with prostitution, but had been under the control of a trafficker named Black who was now demanding that she use her time in prison to recruit other inmates into their circle. She showed him the first of what would turn out to be dozens of letters:

We need a team of like 8 solid bitches who not on no jealous shit and we can not go wrong,” Black wrote in one of his letters to the inmate. “Baby I know there are hoes in there with you and I know you know real people so make it happen.

John Meekins working on a human trafficking presentation in Orlando

It was the first of dozens of similar instances Meekins has encountered. Trafficked women often bounce in and out of correctional facilities on prostitution arrests and while in jail can be used as liaisons for their traffickers to handle in-house recruitment. When the fresh recruit is released, the released inmate’s transition has already been facilitated by mail.

Among Black’s letters to inmates, Meekins found several that provided a window into the methodology. He would ask his targets intimate questions. What were their hopes and dreams when they got out? What did they want? What drugs did they like? Subsequent letters would be filled with promises to fulfil these dreams. They also confirmed the specifics of who would collect them once they were released and what life would be like.

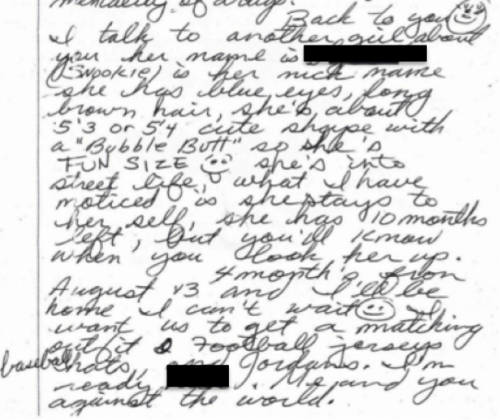

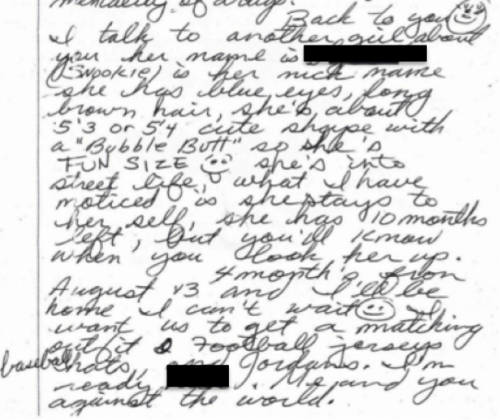

Below is an excerpt from a letter in Meekins’ collection. It’s from a recruiter reporting on her enlistment efforts inside:

I talk to another girl about you, her name is [withheld] (Snookie) is her nick name she has blue eyes, long brown hair, she’s about 5’3 or 5’4 cute shape with a “Bubble Butt” so she’s FUN SIZE (insert smiley) she’s into street life, what I have noticed is she stays to her self, she has 10 months left, but you’ll know when you look her up. 4 months from August 13 and I’ll be home I can’t wait (insert smiley) I want us to get a matching outfit & football jerseys baseball hats, and Jordans. I’m ready [name withheld.] Me and you against the world.

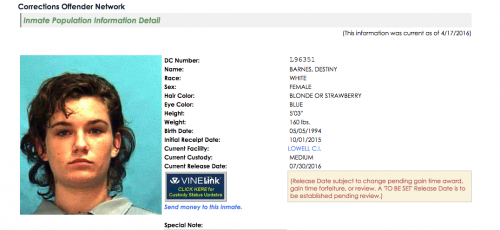

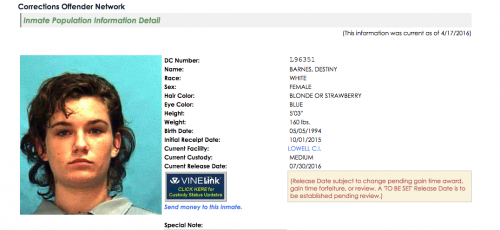

Meekins explained that a letter such as this one would prompt the pimp to reach out to the target and plan how to entice her into his ring. “Heard soooo much about you from my lady,” a trafficker’s letter to a prospect reads. It is dated November 6, 2012 “I feel as tho I already know you. For sure everything I have heard has been positive. You are more than welcome to join our force. As my lady stated we will come pick you up.” He tells her he has seen her photo on the website of the Department of Corrections website. “Think you are a pretty young lady,” he adds.

Jan Miley is a trafficking survivor who spent 11 years under the control of eight different pimps, resulting in more than twenty arrests for prostitution, grand theft auto, and drug possession. The psychological and physical abuse she experienced was extreme. She said that while in prison, she knew she would benefit if she recruited new women into her trafficker’s group and even on the outside, to gain favor for better treatment, would talk other girls she met into coming aboard. “It makes them happy when you bring new girls around,” she said. “That’s more money in their pocket and then you benefit from it as well, maybe for a short time and you only have it one time. But for that a little bit time, you could benefit from it and then they look at you like did something good. It makes you feel good.”

While incarcerated, girls from her stable would keep in contact with their traffickers and inform them about their lives in jail. It is common, Meekins said, for these exchanges to include information about possible new recruits.

Tena Dellaca-Hedrick, another trafficking survivor, has also been a victim advocate at a sexual assault treatment center in Indiana since 2009. She said that during exchanges between a pimp and his new recruit, the women being trafficked will already begin to feel indebted to the prospective new boss. From the beginning of this correspondence, the trafficker will start putting money into the woman’s commissary account —say $10 a month— as a loan.

“What they don’t realize is that $10 comes at extremely high interest rate, so when you get out of prison you might have borrowed $100, or you might have borrowed $500, that $100 is now $10,000 or that $500 might be now $50,000 due to the interest rate piped on the borrowing,” Dellaca-Hedrick said. “So it is kind of shocking, and in the end they find out they cannot work a regular job and pay that back, and the pimp says ‘I got a job for you to pay that back.’ So they are indebted, then, to that human trafficker.”

…in the end they find out they cannot work a regular job and pay that back, and the pimp says ‘I got a job for you to pay that back.’ So they are indebted, then, to that human trafficker.

The traffickers often compound the indebtedness with romance. Through this psychological manipulation, and because the woman comes to believe they are in love, a pimp can make his new prey more accepting of his brutality or the strict rules he imposes. The most important part to understand about these victims, Dellaca-Hedrick said, is that the pattern of psychological torment is particularly acute for those who are “gullible” and “looking for love.”

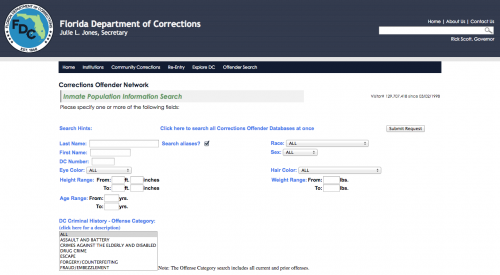

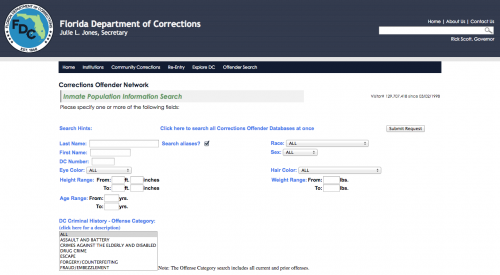

Any categorical search of the DOC website with its publicly available mug shots and individual stats is a marketing bonanza for traffickers. They can easily target fresh supplies of ethnic or age-group demographic best serves their clientele. A categorical search of the site will turn up women by mug shot, crime, release date, physical coloring, height, weight, ethnicity, and age.

Jose Ramirez is a special agent for the Metropolitan Bureau of Investigations, a Florida task force founded in 1978. He is in charge of the unit that works on trafficking cases in central Florida. He told me that the DOC site makes it easy for traffickers to select for the youngest and most attractive girls in the system. “It’s like picking women off a menu,” he said. Since the problem of trafficking has become more evident over the last decade, the bureau now works with FBI, local agencies, and law enforcement to track and capture human traffickers in the area.

Example of a categorial search on the Florida Department of Corrections website

Example of what a query leads to online

It’s like picking women off a menu.

Ramirez’s first successful prosecution of a trafficker took place in 2012. A man in his 70’s, who had been trafficking women for decades, was caught when police found the letters he had been exchanging with an incarcerated female. This was the first of many cases where law enforcement traced traffickers through inmate correspondence. It was also the first trafficking case in Florida in which a pimp’s conviction involved the correctional system.

“In my specific case, the man had a girl within the system who was working as a liaison for him, to recruit girls,” Ramirez said. They also found, as subsequent cases have shown, that the debt inmates were accumulating from money being added to their commissary accounts from outside, known as JPay, was abetting traffickers to have a hold on the women upon release.

Ramirez has joined forces with the American Correctional Association in his efforts to combat prison recruitment. Along with more targeted staff training, he supports a decrease in public access to the personal information about individual inmates.

However, he also realizes that more is needed beyond addressing these obvious structural flaws. That is apparent to Tomas Lares, who co-founded and chairs the Greater Orlando Human Trafficking Task Force. As a collective group, he said, the prevalence of abuse and instability in the personal histories of many inmates makes them particularly vulnerable to traffickers.

“Unfortunately it’s such a breeding ground and such a perfect storm for recruitment because the women are either addicted to a substance, have been arrested multiple times on different charges, or have a history of abuse,” Lares said of the female jail population. “We see the majority of our clients and were abused as a child where there is some form of a neglect or physical abuse. That vulnerability is as at the highest rate. They’re hitting rock bottom.”

Tomas Lares outside a Florida Abolitionist Task Force meeting in March 2016

Lares cited Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to support his observations. Because the women newly out of jail will not have easy access to food, shelter, or clothing, traffickers can entice them with relative luxuries like “drugs, Wendy’s meals and shopping sprees,” he said, and then convince them that sex work will be an expedited means of repayment instead of the actual extortion it is.

The Anti-Trafficking Task Force —”Florida Abolitionists”— is in the earliest phase of creating a program with the University of Central Florida. Their mission is not only to address the systemic problems, but to also educate female jail populations about how to recognize if they are victims of manipulation sexual exploitation. Until the program is underway, the task force has been concentrating on providing training for police officers, correctional staff and other professionals who come into regular contact with victims.

Among these groups are chaplains, who, especially in central Florida, are often very involved with inmates and have proved an excellent source of trafficking identifiers. Since the task force’s first training session for this group back in 2012, the number of reports of both potential victims and recruitment has increased significantly. Despite all the independent attention the issue is receiving in the region, the Florida Department of Corrections has not increased its efforts to investigate the reports that have been filed.

Ramirez emphasized that despite the various independent efforts in central Florida, without appropriate training for correctional personnel, officials will not even be able to recognize signs of trafficking to report to the bureau.

“It’s not easy to identify someone that might be involved in trafficking in the jails,” Ramirez said. “We have been working on how to develop some kind of training. A lot of stuff this is being done of across the nation, so I want to find out what kind of tools we’re going to use, and what kind of training to utilize to train all correctional people.”

Central Florida has plenty of company in its need for training. An informal survey of 41 state correctional departments indicated that 27 of them have no mandatory training in human trafficking. If a corrections officer wants to receive training after hearing about the issue from an outside source, he or she can voluntarily access it. But for anything more than a skimpy two-hour online education, it will likely involve taking time off work and travel that would not be compensated.

Central Florida has plenty of company in its need for training. An informal survey of 41 state correctional departments indicated that 27 of them have no mandatory training in human trafficking. If a corrections officer wants to receive training after hearing about the issue from an outside source, he or she can voluntarily access it. But for anything more than a skimpy two-hour online education, it will likely involve taking time off work and travel that would not be compensated.

Anti-trafficking nonprofit organizations such as Safe Horizon, GEMS, and Polaris Project have taken on some of the burden of training these officers, believing that more awareness and education for prison officials will enable more victims to be identified and ultimately decrease the number of jailhouse recruiters. But with the limited resources the nonprofits have, a comprehensive training program is beyond their capacity.

“We do what we can to train officers in the correctional system,” said Lindsey Speed, a staff member at Traffick 911, a Dallas-based nonprofit. “We will go to the location and offer a two-hour introductory course if they ask us to. But it can be hard to reach everyone, and there is just too much on the subject to be fit into two hours.”

This training typically involves a powerpoint presentation, during which a volunteer from the nonprofit will guide the audience through the definition of trafficking, available statistics, signs of exploitation, and how to identify and converse with potential victims. This lesson could include learning to spot certain types of tattoos, with which pimps often “brand” their girls as a sign to other traffickers, or to recognize signs of abuse, such as a woman’s discomfort in making direct eye contact.

However informative and useful the sessions may be, they do come with drawbacks. First, nonprofits only are allowed to visit the facilities that invite them, leading to inconsistencies in which officers receive the training, and how often. Second, nonprofits against trafficking are very often faith-based, so training can involve opening prayers and religious references, which deters some officers from signing up.

Meekins elaborated on the issue with faith-based programs. “Although they mean well,” he said, “they are super religious. So in order to get trained, or for a girl to get help, they have to subscribe to what these people are saying about their religion. . . . But I guess it’s better than nothing.”

Meekins conducted a survey among trafficking victims in Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala Florida to highlight the lack of consistent staff training. He asked the women what officers could have done better in handling their cases.

“Human Trafficking Survivor No. 1” responded by recounting the beating and sexual assault she endured on the street at the hands of a stranger. She also recalled how police dropped the investigation as soon as they the two previous arrests for prostitution on her rap sheet. “When they looked at my record, they figured I was on a date & it got out of hand,” she wrote. Officers, without the benefit of training, did not consider any other possibilities.

As many trafficking survivors report, what was labeled “prostitution” was actually a case of forced sex labor. “ASK QUESTIONS” was the second part of her reply to Meekins’ questionnaire. “Ask why they are doing it, are they being forced, do they need help,” she wrote. “Don’t belittle & treat every girl who is convicted of prostitution as something not serious.”

Ask why they are doing it, are they being forced, do they need help. Don’t belittle & treat every girl who is convicted of prostitution as something not serious.

Meekins responded to his survey findings by expanding his his anti-trafficking campaign at the Ocala facility. He collaborated with American Military University to create information packs: 4X6 red cards with 16 signs of trafficking listed on one side, and a list of standard questions to ask a suspected victim on the other.

“Have you ever engaged in prostitution? If so, how were you introduced to it?” reads the fifth of six questions. The rest of the queries involve employment, boyfriends, and criminal pasts. Meekins is cognizant of the link between women being involved with trafficking rings, romantic entanglements, sketchy job histories, and earlier convictions for crimes other than prostitution.

His mission is gaining traction. The Inspector General of Florida, Melinda M. Miguel, has recently worked with Meekins through the month of April to investigate the three female prisons in the state and come up with a program to train officers in human trafficking and address the prevalence of recruitment operations and overlooked victims within the facilities.

Survivors themselves, like Dellaca-Hedrick in Indiana and Alles in Florida have been important in driving the change in response. Tajuan McCarty, another human trafficking survivor, founded WellHouse in Alabama for victims of trafficking. She was arrested “more times than she can even remember” during her 10 years of being trafficked. Not once, she said, was she ever asked how she accumulated more than ten prostitution arrests, nor was she screened for trafficking.

“I kept getting arrested for prostitution, but that’s not what it was,” McCarty said. “I was under the control of a trafficker. But the officers didn’t care, they didn’t ask. I was just another prostitute in there, and was treated as such.”

Eventually she escaped her trafficker, went back to school, and opened a safe house for other exploited women, who, she said, also received prostitution records in place of investigations when they came into contact with officers. However, if victims are fortunate enough to escape the control of a trafficker, prostitution arrests can make their rehabilitation process and assimilation back into society incredibly difficult.

Brent Woody, a Florida State University Law School graduate, has taken it upon himself to help rehabilitate victims and get their haunting criminal records expunged. “If they can get those records expunged,” Woody said, “it opens a whole new world for them to be able to get funding and scholarships and help they need to start a new life, because they’re not criminals, they’re victims.”

In 2013, Woody worked with a state legislative team to pass a statute that allows this expungement if the women can prove at trial that they were under a trafficker’s control at the time of their arrest. Woody helps the women to collect the official documentation of their cases which matches federal human trafficking definition standards. Since the legislation became state law three years ago, he has been successful in all 12 cases he has taken on.

This Florida expungement law followed legislation first passed by New York in 2010 that allowed for the sealing victims’ records. Fifteen other states followed, forcing courts to seriously consider that trafficking might be behind some prostitution cases. Currently, 27 states also have vacature laws in place, which offer women some kind of restitution if they can prove that they were trafficked. They too can have their records sealed or cleared.

Former Chief State Judge of New York, Jonathan Lippman, started one of the first task forces in the country dedicated to helping trafficking victims who had been wrongly convicted of prostitution. It is made up of “judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, members of law enforcement, legislators, executive branch officials, forensic experts, victim’s advocates and legal scholars” its website says.

Lippman also opened Human Trafficking Courts in the state, providing women charged with prostitution with a place to have their arraignments held where there was an option other than plea or go to trial. In these new courts, women would automatically be considered for a six month rehabilitation program. If they have no further incidents, the charges could be dropped.

“The focus should be on the demand, on the traffickers and the buyers,” Lippman said in a 2014 New York Times article. “The reality is we don’t make decisions as to who gets arrested, and we want to assure that these victims get the assistance that they need and ultimately get out of ‘the life.’”

To manage the women brought into these courts, Lippman, in 2009, appointed Leigh Latimer to be in charge of the defense of women charged with prostitution. At the time, Latimer had spent more than 20 years working for the Legal Aid Society in New York, aiding and defending those who could not afford legal representation. Although she worked heavily with those faced with drug charges, she always held a special place in her heart for women charged with prostitution. She had noticed throughout her career that these women seemed generally to have been subjected to some kind of abuse or exploitation.

Although not all of her clients were necessarily victims of sex trafficking, the opening of the Human Trafficking Courts combined with human trafficking training —which the Legal Aid Society now offers to others, including law enforcement, judges and lawyers— helped her better understand how victims of human trafficking ended up with prostitution charges. Through a long and grueling process that can take up to two years to complete, she has helped dozens of victims get their records sealed.

The Legal Aid Society is not obligated to screen for trafficking in those it represents, but if trafficking is detected, the lawyers are trained to respond appropriately and lead victims to necessary services. “If clients do disclose trafficking, then there may be other levels of work we can do with them,” Latimer said. Although they treat every client the same, if trafficking is suspected and confirmed, the lawyers know how to converse and seek medical and psychological care for them, unlike many other professionals that come into contact with victims.

When Meekins first began his fight against human trafficking in the correctional system in 2010, his reach was limited to Central Florida. But within a year, he had joined Shared Hope International and the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators, organizations that deal with prevention and awareness. Meekins began making presentations around the country, including to the American Correctional Association, hoping to influence other correctional officers to take note of what was going on with women in their care.

When Meekins first began his fight against human trafficking in the correctional system in 2010, his reach was limited to Central Florida. But within a year, he had joined Shared Hope International and the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators, organizations that deal with prevention and awareness. Meekins began making presentations around the country, including to the American Correctional Association, hoping to influence other correctional officers to take note of what was going on with women in their care.

After hearing a presentation Meekins made in 2013, where he shared statistics and testimonies from trafficking victims who had been incarcerated, James Basinger, Indiana’s the Deputy Commissioner of Operations, had an epiphany similar to the one Meekins experienced in 2010. Perhaps he too had overlooked signs of trafficking in women under his supervision.

When he returned from the conference in Florida, Basinger contacted the Attorney General’s office in Indiana and sought training for the staff of the women’s correctional facilities. He was put in touch with IPATH —Indiana Protection for Abused and Trafficked Humans— to set up a training session for Indiana’s correctional staff of the female institution.

Almost immediately, correctional officers and other employees were put through mandatory training to recognize and respond to signs of sexual abuse in inmates. And within a few months, a recruiter was identified in the women’s prison, communicating to her trafficker in the same manner Meekins had explained from his experiences in Florida.

“There was an incident where females were trying to recruit other females —vulnerable females at the institutions— to get them involved in sex trafficking once they were released,” said Sandra Kibby-Brown, an operations officer in the Indiana Department of Corrections. “These were usually females that had no support upon their release— meaning family and friends— no longer having anything to do with them or where there were challenges or disabilities.”

Kibby-Brown says that the training opened the eyes of prison staff to signs that had always existed, but they did not have the knowledge to recognize. However, with training, officers could oversee inmate’s relationships with their visitors and the terms and codes they used in frequent phone calls and correspondence with traffickers.Kibby-Brown explained that before the training program, “nobody was thinking in terms of slavery” when it came to women in jail for prostitution.

Nobody was thinking in terms of slavery.

The correctional department is now working with Indiana State University to create its own curriculum apart from IPATH’s. But instead of being exclusively for the staff, the department is looking into adapting programs from victim service centers into a learning unit specifically for incarcerated women.

The program would explain what exactly constitutes trafficking, as many women under control of their pimps do not even realize they are being abused, nor that they are legally considered victims and entitled to restitution. Instead, their pimps have convinced their victims that they are willing participants in the abuse and sex work, similar to Stockholm Syndrome. The classes would also give the women access to avenues through which they could report their suspected trafficking. The curriculum would also target those who are vulnerable to recruitment schemes. The goal would be to offer this voluntary class to all inmates, but particularly those at high risk for trafficking.

Ohio women’s prisons are already implementing these kinds of classes for their populations. Although Ohio’s Department of Corrections has not been as aggressive against trafficking as Indiana’s, some individual staff members in the Higher Risk Trade Center for Women have implemented ideas they picked up in voluntary, off-the-clock training events.

Heidi Bishop, an Ohio Department of Corrections staff member, is one of these employees. Bishop received her master’s degree in Social Work from Ohio State in 2014, the same year that the Attorney General of Ohio, Mike DeWine, implemented a mandatory screening program for human trafficking upon women’s entry into the prison system. If the screening reveals that a woman has been trafficked, she is put into a specialized program for prison populations that Bishop created. Bishop estimates that two to three new trafficking victims enter the prison each month.

In Ohio,there is nothing Bishop can do to eradicate the victims’ prison sentences, however, she runs an educational program that is geared towards helping them out of “the life” once their time is served. The classes last up to 16 weeks, and are essentially roundtable discussions led by Bishop and a Salvation Army representative. Each session consists of the same group of identified victims, and discusses what trafficking is, how pimps exploit their girls, and the impact of psychological issues of shame and disgust. Every couple of months, a new round of sessions begins for incoming women once the previous group has “graduated.”

Beyond receiving victims of trafficking, the Ohio reformatory has also — consistent with Indiana and Florida — found incidents of recruitment within its facility. Bishop says it usually happens during a woman’s first 30 to 45 days in reception, because this time is hardest for new inmates to find work duty and make any money, which leaves them dependent on their families and friends. If they don’t receive financial assistance, they are particularly vulnerable to the JPay trafficker arrangement.

However, despite Bishop and colleagues having detected and attempted to respond to this problem, the reformatory is understaffed and undertrained. Bishop, as a social worker, already has a caseload of about 100 inmates apart from her work in anti-trafficking, where she deals with issues ranging from inmate relationships to addiction to domestic violence. So when a trafficking victim is identified and she is expected to provide her services, Bishop is adding that client on top of a load she is already stretched thinly across.

“When I have all those survivors that are being referred to me, 85-90 percent of times they aren’t my clients to begin with, so I am kind of adding clients to my caseload and it’s is hard because my main priority is larger than the area I am responsible for,” Bishop said. “So it’s maybe extra time goes to a human trafficking survivor that has contacted me for help. It is a hard balance, trying to give them the services that they need but not having all that time I need to do that.”

Another issue that the reformatory faces is a lack of manpower. Every prison has an investigation team that handles internal issues, such as rape allegations, staff abusing inmates, and drug activity. These investigators in Ohio have been trained in human trafficking issues, but for the reformatory’s 2,600 inmates, there are only two investigators responsible for all internal criminal investigations. This leaves no time to screen every single phone call and letter with the necessary detail to catch nuances that indicate a trafficking instance, regardless of how well trained the investigators might be.

The National Institute of Corrections is “well aware that a too high percentage of incarcerated women have been victims of human trafficking and know that there is increasing ‘in reach’ to prisons and jails from traffickers through a variety of means,” according to an email response from Maureen Buell, a Correctional Program Specialist at the Bureau of Prisons in Washington, D.C. Buell also said that the National Institute of Corrections “might be” taking steps against these problems in the future. But as of now, even as aware as it is of the issue, there is no action being taken from the federal control station of U.S. correctional institutions.

Also, given the fact that of the 27 states with no training programs, nine responded that they are not aware of any trafficking issues whatsoever in the prison system.

Buell and Meekins both recommended that I reach out to Evelyn Bush, the Correctional Program Specialist of the Prisons Division for the National Institute of Corrections. She has taken an interest in trafficking in the criminal justice system and made presentations for the American Correctional Association on the topic. However, Ms. Bush did not reply to [five] phone and email inquiries.

In response to the fact that the Institute has created no anti trafficking program in response to the issue despite knowledge of its occurrence, Alles believes cost a larger factor than the safety of the women. “How dare they put a price tag on a woman’s head,” she wrote in an email in April, after the Institute had responded to my inquiries after several months. “Shame on them. Now I fight harder to change laws!”

How dare they put a price tag on a woman’s head. Shame on them. Now I fight harder to change laws!

While in Florida, Alles walked me up to a small, one-story building nestled at the back of several acres of wooded land behind her church, forty-five minutes north of the Disney-inhabited area of Orlando. “It’s quiet out here,” she commented as she opened the back door, which was unlocked. “The girls will like that, I think.”

The building served as a schoolhouse for a Haitian community in the area until 2005, when the school shut down and the property was returned to The Love Church. Since then, the building had fallen into disuse, until the church director called Alles in 2014 and gave it to her to open a safe house for the girls, on the condition that she was willing to repair it herself.

We walked down a long hallway, passing two common areas with old couches and school desks cluttered in the corners. There are three large sleeping areas, a kitchen crying out for renovation, and a bathroom with a newly donated shower and toilet that looked out of place beside the dilapidated walls and cracked tiles.

Alles has thrown herself into the project, mostly alone. Donations are financing her repairs, supplemented by her own savings and earnings. She has worked at call centers and collection agencies and has also waitressed. For now the house is only inhabited by donation boxes of women’s clothes and bedding materials, all sitting alongside stacks of elementary school books and blackboards with fifth grade vocabulary words barely visible from the early 2000’s. But within the next six months, Alles hopes to bring her first girl home.

“It’s got a long way to go, but it’s a good place to start,” she said as she took a seat in her back office, moving stacks of papers and letters off a chair to offer me a place to sit. Clearly, she was usually in the space alone.

Views of the safe house Alles is working to refurbish

When the repairs are finished, Alles is determined to fill the house with women trying to escape their traffickers, never turning a woman away if she has a bed available.

“I’m just going keep showing my face and let them know that I’m real, I’m not about games,” Alles said of the girls on the street. “There’s no law enforcement behind me to get them, it’s just me— Big Baby,” she continued. “It’s just the same person you knew then, someone not on drugs that will help you. There’s no doorman at this house and there’s a bed, and you can sleep, and you’re not going to wake to someone beating you. No gimmicks, just real life.”

There’s no doorman at this house and there’s a bed, and you can sleep, and you’re not going to wake to someone beating you.

The car ride was mostly silent after the long day together, except for Alles quietly humming along with the gospel station she still had playing and occasionally asking me if I was ok.

We pulled up to the Days Inn right as the sun set. She asked if I was would be all right getting back to my room. I gave her a quizzical look as I zipped up my camera bag.

“I wasn’t going to say anything,” she said as she put the car in park. “But this hotel was one of the places where I was frequently trafficked.”

I scurried towards the lobby as she pulled away, nervously glancing around before hurrying to my hotel room and bolting the door behind me.

*John Meekins spoke to me for this article independently. He in no way represents the views of Lowell Correctional Facility.

Larson Binzer is a recent graduate from New York University, where she studied political science and journalism, graduating with honors. She was a senior editor for the student newspaper Washington Square News, and interned at several anti-trafficking nonprofits and as a press intern on Capitol Hill. Originally from Texas, she now lives in New York City where she is a District Representative for Rep. Carolyn Maloney and plans on attending law school in the fall of 2017.

Larson Binzer is a recent graduate from New York University, where she studied political science and journalism, graduating with honors. She was a senior editor for the student newspaper Washington Square News, and interned at several anti-trafficking nonprofits and as a press intern on Capitol Hill. Originally from Texas, she now lives in New York City where she is a District Representative for Rep. Carolyn Maloney and plans on attending law school in the fall of 2017.

Aubree Alles looks like any other overworked 36-year-old. Between going back to school, staying involved in her local church, and raising her ten-year-old daughter, she functions on very little sleep and refers to her driver seat of her 2007 Dodge Ram as a second home, office, and call center. No one would ever guess that it has been only five years since the busy mom from Orlando narrowly escaped a life of rape, drugs, and violence.

While serving time for drug possession in 2001, Alles, who was 20 at the time, bonded with her pregnant bunkmate, Rawz, over their shared love of children and history of substance abuse. Both were released at about the same time and Rawz offered Alles room and board in exchange for help around the house and Alles gratefully agreed.

Over the next several months, Alles would not be the woman’s only young houseguest, as many homeless teenagers settled into the apparent haven. From household chores, Rawz promoted Alles to the role of chauffeur and instructed her to drive their housemates to different locations around Orlando, wait outside, and then escort the disheveled women home a half hour later. Alles buried her disgust, thankful for shelter and the consistent supply of the drugs her housemother made available. But when on one of these outings, the girl’s client decided he wanted Alles instead, she joined those who were being regularly being ushered in and out of back doors and motel rooms. Rawz threatened her with eviction or beatings if she did not cooperate.

Alles standing outside an abandoned hotel, where she once lived for several months with her trafficker in room 21

So Alles quickly developed a steady clientele and lived a life coerced into commercial sex at the hands of Rawz and her associates. In that time, Alles amassed a record of 23 criminal convictions for petty crimes and prostitution. And yet in almost two dozen stints in various jails and prisons around central Florida, no one ever thought to ask about what actually had caused her to join the ranks of 49,000 to 56,000 women arrested on prostitution charges annually.

Traffickers, it turns out, have identified the prison system as fertile recruitment territory for their “stables.” Female prison facilities are filled with women serving out sentences for prostitution but who, in fact, are unrecognized victims of human trafficking. They’ve been brought into the life in one of two ways: through manipulators on the inside, like Rawz, who promise their prisonmates stability and employment once they both are released. Or, from the outside, traffickers will seek out young or naive inmates through public records that they sense will be vulnerable to exploitation. The correspondence they initiate leads to similar offers.

Another of the hotels in Orlando where Alles was trafficked

Only recently have prison systems begun to realize how much their correctional officers need to be trained to recognize the signs of trafficking in their midst. For the most part, prison staff are not keyed to spot signs of trafficking among women inmates, or how to look for indicators of recruitment among inmates under their supervision. Although a handful of states have begun to implement training programs to raise the level of awareness in their institutions, most correctional departments have no human trafficking training program at all, and, when asked, had no awareness that prison recruitment is an issue.

In her 23rd prison stint, Alles was finally asked how she had ended up in jail, but not by a correctional officer. Rather, she was approached by a chaplain making rounds who was willing to listen to Alles’ history. The chaplain pieced together that there may have been a more complex tale behind Alles’ prostitution charges. The woman eventually led Alles to a nonprofit organization, Samaritan’s Village, that helped her leave the abusive life with Rawz behind her. None of this assistance came to Alles from the system that incarcerated her.

Alles sorting through donations to the safe house she is working to refurbish, March 2016

In redefining her life, Alles is opening a safe house for other victims of human trafficking where they can come to heal and get help. The Love Church in Orlando has provided her with a three-bedroom refuge for the women and administrative assistance.

“Victoria just called me and said ‘it’s time,’” Alles said of the leader of the church. “She said I’d have to fix it up myself, that it would be hard, but that if I was willing to do it, I could have the house for free to take care of the girls.”

![]() We drove north along the trail — Floridians call it the “OBT,” a road that stretches 433 miles vertically across the state — before Alles abruptly slammed on the brakes to make a quick U-turn. “I remember her!” she cried out, gesturing to a woman on a street corner who was leaning against a white Mustang at a stop sign. “We used to work out here together.” This was one of the streets Alles’ trafficker used to put her out on.

We drove north along the trail — Floridians call it the “OBT,” a road that stretches 433 miles vertically across the state — before Alles abruptly slammed on the brakes to make a quick U-turn. “I remember her!” she cried out, gesturing to a woman on a street corner who was leaning against a white Mustang at a stop sign. “We used to work out here together.” This was one of the streets Alles’ trafficker used to put her out on.

Alles pointed to the darkened enclaves of Orange Blossom Trail as she drove down the street.“It got to the point around here,” she said, “where if a man told a cab driver to ‘take him to the girls,’ the cabbie would know exactly where to go here,” She switched the pop music that was playing on her car radio to the gospel station.

Another hotel where Alles was trafficked along Orange Blossom Trail

After the Mustang pulled away, Alles pulled up alongside the street and called out to the woman—Diane— over and away from a lanky man half perched on a bicycle. Diane was a short black woman with a kind smile and a full bosom that was escaping her white camisole. Her shoulder length hair needed a wash. “Big Baby! Is that you?” Diane yelled, hastening toward the car as soon as she recognized Alles, despite a limp in her right leg. Diane wasn’t one of Rawz’s girls, but she and Alles worked the same area for five years.

The two caught up for several minutes, discussing jobs, mutual friends, and their children.

Finally, Alles offered the woman “hygiene,” handing over a small zip lock filled with sample sized soaps and a hot pink loofa. Alles kept these toiletry bags premade in her car to give to women on the street, as traffickers often don’t provide basic cleaning materials. “Even if they don’t have their own bathroom, at least they can go into a public bathroom and take care of themselves a little bit, to feel like a person again,” Alles would say later.

To Diane, she said, “If you ever want to get out of the life, you give me a call.You don’t have to be ready, you just call me and we’ll do it together.” They exchanged numbers and hugged, and Alles glanced over at the man on the bicycle, who had carefully watched the encounter. “Tell Money to be good,” Alles said before quickly pulling away from Diane’s work corner.

Behind Alles’ truck, Money climbed onto his bike and followed us, pulling up to the driver’s side while we waited to make the turn back onto OBT northbound. “Big Baby?” he said through the half-open window, only his tattered Florida State shirt visible to me in the passenger seat. “Nice wheels. You must be doing good for yourself.” He smiled and pushed his arm into the car to touch Alles’ shoulder. “I love you,” he finished as the road opened up for us to merge.

Alles shivered and let out a disgusted sound as he peddled away. “I haven’t seen him in five years,” she said, explaining that Money was Rawz’s doorman, and someone everyone knew but no one messed with. “He used to stand guard outside the door while she beat me for hours so no one could come in.”

He used to stand guard outside the door while she beat me for hours so no one could come in.”

Money was also the man who intercepted Alles the first time she tried to escape, the failed attempt that led to one six-hour beating. It was this experience that strengthened her determination to escape, even if it cost her her life.

![]() Alles explained that the absence of a pimp or trafficker in the vicinity of a woman selling sex does not mean she is doing so of her own volition. “Ninety percent of the time, women choosing prostitution as their means of supporting themselves are not going to be out here on the street corner,” Alles said. “They’re going to be on backpage or the ‘high class’ ways of finding work.” For the trafficked, the situation is different. “If you’ve got threats against your life, or are hooked on drugs,” she said, “you’re going to do what you have to do.”

Alles explained that the absence of a pimp or trafficker in the vicinity of a woman selling sex does not mean she is doing so of her own volition. “Ninety percent of the time, women choosing prostitution as their means of supporting themselves are not going to be out here on the street corner,” Alles said. “They’re going to be on backpage or the ‘high class’ ways of finding work.” For the trafficked, the situation is different. “If you’ve got threats against your life, or are hooked on drugs,” she said, “you’re going to do what you have to do.”

Human trafficking experts explain that victims are given a daily quota to meet, usually between $500-$1,000, Alles said. They are told that if they come back with less, they will be beaten, starved, or deprived of drugs. Traffickers will also convince the women of their love for them. They may assure them of posting bail in the event of an arrest but then threaten to revoke it if the woman misbehaves. They create a vicious cycle of loyalty and debt that will not be forgiven.

![]() For the past six years, John Meekins* has been studying the jailhouse recruitment of women into human trafficking rings. As correctional officer at the Lowell Correctional Institution in central Florida, he happened to attend a seminar conducted by the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators back in 2010. This voluntary training was the first instruction on sex trafficking that he ever received. It made him think back to earlier parts of his career and the obvious signs of trafficking and abuse that he had missed. This prompted him to begin a “low key” anti-trafficking campaign in his prison by putting up posters that defined human trafficking and provided information about how to report it to prison authorities. The administration has allowed his self-styled campaign but has not officially endorsed it.

For the past six years, John Meekins* has been studying the jailhouse recruitment of women into human trafficking rings. As correctional officer at the Lowell Correctional Institution in central Florida, he happened to attend a seminar conducted by the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators back in 2010. This voluntary training was the first instruction on sex trafficking that he ever received. It made him think back to earlier parts of his career and the obvious signs of trafficking and abuse that he had missed. This prompted him to begin a “low key” anti-trafficking campaign in his prison by putting up posters that defined human trafficking and provided information about how to report it to prison authorities. The administration has allowed his self-styled campaign but has not officially endorsed it.

Several weeks after he began his efforts, an offender approached Meekins and told him that she had been charged with prostitution, but had been under the control of a trafficker named Black who was now demanding that she use her time in prison to recruit other inmates into their circle. She showed him the first of what would turn out to be dozens of letters:

We need a team of like 8 solid bitches who not on no jealous shit and we can not go wrong,” Black wrote in one of his letters to the inmate. “Baby I know there are hoes in there with you and I know you know real people so make it happen.

John Meekins working on a human trafficking presentation in Orlando

It was the first of dozens of similar instances Meekins has encountered. Trafficked women often bounce in and out of correctional facilities on prostitution arrests and while in jail can be used as liaisons for their traffickers to handle in-house recruitment. When the fresh recruit is released, the released inmate’s transition has already been facilitated by mail.

Among Black’s letters to inmates, Meekins found several that provided a window into the methodology. He would ask his targets intimate questions. What were their hopes and dreams when they got out? What did they want? What drugs did they like? Subsequent letters would be filled with promises to fulfil these dreams. They also confirmed the specifics of who would collect them once they were released and what life would be like.

Below is an excerpt from a letter in Meekins’ collection. It’s from a recruiter reporting on her enlistment efforts inside:

I talk to another girl about you, her name is [withheld] (Snookie) is her nick name she has blue eyes, long brown hair, she’s about 5’3 or 5’4 cute shape with a “Bubble Butt” so she’s FUN SIZE (insert smiley) she’s into street life, what I have noticed is she stays to her self, she has 10 months left, but you’ll know when you look her up. 4 months from August 13 and I’ll be home I can’t wait (insert smiley) I want us to get a matching outfit & football jerseys baseball hats, and Jordans. I’m ready [name withheld.] Me and you against the world.

Jan Miley is a trafficking survivor who spent 11 years under the control of eight different pimps, resulting in more than twenty arrests for prostitution, grand theft auto, and drug possession. The psychological and physical abuse she experienced was extreme. She said that while in prison, she knew she would benefit if she recruited new women into her trafficker’s group and even on the outside, to gain favor for better treatment, would talk other girls she met into coming aboard. “It makes them happy when you bring new girls around,” she said. “That’s more money in their pocket and then you benefit from it as well, maybe for a short time and you only have it one time. But for that a little bit time, you could benefit from it and then they look at you like did something good. It makes you feel good.”

While incarcerated, girls from her stable would keep in contact with their traffickers and inform them about their lives in jail. It is common, Meekins said, for these exchanges to include information about possible new recruits.

Tena Dellaca-Hedrick, another trafficking survivor, has also been a victim advocate at a sexual assault treatment center in Indiana since 2009. She said that during exchanges between a pimp and his new recruit, the women being trafficked will already begin to feel indebted to the prospective new boss. From the beginning of this correspondence, the trafficker will start putting money into the woman’s commissary account —say $10 a month— as a loan.

“What they don’t realize is that $10 comes at extremely high interest rate, so when you get out of prison you might have borrowed $100, or you might have borrowed $500, that $100 is now $10,000 or that $500 might be now $50,000 due to the interest rate piped on the borrowing,” Dellaca-Hedrick said. “So it is kind of shocking, and in the end they find out they cannot work a regular job and pay that back, and the pimp says ‘I got a job for you to pay that back.’ So they are indebted, then, to that human trafficker.”

…in the end they find out they cannot work a regular job and pay that back, and the pimp says ‘I got a job for you to pay that back.’ So they are indebted, then, to that human trafficker.

The traffickers often compound the indebtedness with romance. Through this psychological manipulation, and because the woman comes to believe they are in love, a pimp can make his new prey more accepting of his brutality or the strict rules he imposes. The most important part to understand about these victims, Dellaca-Hedrick said, is that the pattern of psychological torment is particularly acute for those who are “gullible” and “looking for love.”

Any categorical search of the DOC website with its publicly available mug shots and individual stats is a marketing bonanza for traffickers. They can easily target fresh supplies of ethnic or age-group demographic best serves their clientele. A categorical search of the site will turn up women by mug shot, crime, release date, physical coloring, height, weight, ethnicity, and age.

Jose Ramirez is a special agent for the Metropolitan Bureau of Investigations, a Florida task force founded in 1978. He is in charge of the unit that works on trafficking cases in central Florida. He told me that the DOC site makes it easy for traffickers to select for the youngest and most attractive girls in the system. “It’s like picking women off a menu,” he said. Since the problem of trafficking has become more evident over the last decade, the bureau now works with FBI, local agencies, and law enforcement to track and capture human traffickers in the area.

Example of a categorial search on the Florida Department of Corrections website

Example of what a query leads to online

It’s like picking women off a menu.

Ramirez’s first successful prosecution of a trafficker took place in 2012. A man in his 70’s, who had been trafficking women for decades, was caught when police found the letters he had been exchanging with an incarcerated female. This was the first of many cases where law enforcement traced traffickers through inmate correspondence. It was also the first trafficking case in Florida in which a pimp’s conviction involved the correctional system.

“In my specific case, the man had a girl within the system who was working as a liaison for him, to recruit girls,” Ramirez said. They also found, as subsequent cases have shown, that the debt inmates were accumulating from money being added to their commissary accounts from outside, known as JPay, was abetting traffickers to have a hold on the women upon release.

Ramirez has joined forces with the American Correctional Association in his efforts to combat prison recruitment. Along with more targeted staff training, he supports a decrease in public access to the personal information about individual inmates.

However, he also realizes that more is needed beyond addressing these obvious structural flaws. That is apparent to Tomas Lares, who co-founded and chairs the Greater Orlando Human Trafficking Task Force. As a collective group, he said, the prevalence of abuse and instability in the personal histories of many inmates makes them particularly vulnerable to traffickers.

“Unfortunately it’s such a breeding ground and such a perfect storm for recruitment because the women are either addicted to a substance, have been arrested multiple times on different charges, or have a history of abuse,” Lares said of the female jail population. “We see the majority of our clients and were abused as a child where there is some form of a neglect or physical abuse. That vulnerability is as at the highest rate. They’re hitting rock bottom.”

Tomas Lares outside a Florida Abolitionist Task Force meeting in March 2016

Lares cited Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to support his observations. Because the women newly out of jail will not have easy access to food, shelter, or clothing, traffickers can entice them with relative luxuries like “drugs, Wendy’s meals and shopping sprees,” he said, and then convince them that sex work will be an expedited means of repayment instead of the actual extortion it is.

The Anti-Trafficking Task Force —”Florida Abolitionists”— is in the earliest phase of creating a program with the University of Central Florida. Their mission is not only to address the systemic problems, but to also educate female jail populations about how to recognize if they are victims of manipulation sexual exploitation. Until the program is underway, the task force has been concentrating on providing training for police officers, correctional staff and other professionals who come into regular contact with victims.

Among these groups are chaplains, who, especially in central Florida, are often very involved with inmates and have proved an excellent source of trafficking identifiers. Since the task force’s first training session for this group back in 2012, the number of reports of both potential victims and recruitment has increased significantly. Despite all the independent attention the issue is receiving in the region, the Florida Department of Corrections has not increased its efforts to investigate the reports that have been filed.

Ramirez emphasized that despite the various independent efforts in central Florida, without appropriate training for correctional personnel, officials will not even be able to recognize signs of trafficking to report to the bureau.

“It’s not easy to identify someone that might be involved in trafficking in the jails,” Ramirez said. “We have been working on how to develop some kind of training. A lot of stuff this is being done of across the nation, so I want to find out what kind of tools we’re going to use, and what kind of training to utilize to train all correctional people.”

![]() Central Florida has plenty of company in its need for training. An informal survey of 41 state correctional departments indicated that 27 of them have no mandatory training in human trafficking. If a corrections officer wants to receive training after hearing about the issue from an outside source, he or she can voluntarily access it. But for anything more than a skimpy two-hour online education, it will likely involve taking time off work and travel that would not be compensated.

Central Florida has plenty of company in its need for training. An informal survey of 41 state correctional departments indicated that 27 of them have no mandatory training in human trafficking. If a corrections officer wants to receive training after hearing about the issue from an outside source, he or she can voluntarily access it. But for anything more than a skimpy two-hour online education, it will likely involve taking time off work and travel that would not be compensated.

Anti-trafficking nonprofit organizations such as Safe Horizon, GEMS, and Polaris Project have taken on some of the burden of training these officers, believing that more awareness and education for prison officials will enable more victims to be identified and ultimately decrease the number of jailhouse recruiters. But with the limited resources the nonprofits have, a comprehensive training program is beyond their capacity.

“We do what we can to train officers in the correctional system,” said Lindsey Speed, a staff member at Traffick 911, a Dallas-based nonprofit. “We will go to the location and offer a two-hour introductory course if they ask us to. But it can be hard to reach everyone, and there is just too much on the subject to be fit into two hours.”

This training typically involves a powerpoint presentation, during which a volunteer from the nonprofit will guide the audience through the definition of trafficking, available statistics, signs of exploitation, and how to identify and converse with potential victims. This lesson could include learning to spot certain types of tattoos, with which pimps often “brand” their girls as a sign to other traffickers, or to recognize signs of abuse, such as a woman’s discomfort in making direct eye contact.

However informative and useful the sessions may be, they do come with drawbacks. First, nonprofits only are allowed to visit the facilities that invite them, leading to inconsistencies in which officers receive the training, and how often. Second, nonprofits against trafficking are very often faith-based, so training can involve opening prayers and religious references, which deters some officers from signing up.

Meekins elaborated on the issue with faith-based programs. “Although they mean well,” he said, “they are super religious. So in order to get trained, or for a girl to get help, they have to subscribe to what these people are saying about their religion. . . . But I guess it’s better than nothing.”

Meekins conducted a survey among trafficking victims in Lowell Correctional Institution in Ocala Florida to highlight the lack of consistent staff training. He asked the women what officers could have done better in handling their cases.

“Human Trafficking Survivor No. 1” responded by recounting the beating and sexual assault she endured on the street at the hands of a stranger. She also recalled how police dropped the investigation as soon as they the two previous arrests for prostitution on her rap sheet. “When they looked at my record, they figured I was on a date & it got out of hand,” she wrote. Officers, without the benefit of training, did not consider any other possibilities.

As many trafficking survivors report, what was labeled “prostitution” was actually a case of forced sex labor. “ASK QUESTIONS” was the second part of her reply to Meekins’ questionnaire. “Ask why they are doing it, are they being forced, do they need help,” she wrote. “Don’t belittle & treat every girl who is convicted of prostitution as something not serious.”

Ask why they are doing it, are they being forced, do they need help. Don’t belittle & treat every girl who is convicted of prostitution as something not serious.

Meekins responded to his survey findings by expanding his his anti-trafficking campaign at the Ocala facility. He collaborated with American Military University to create information packs: 4X6 red cards with 16 signs of trafficking listed on one side, and a list of standard questions to ask a suspected victim on the other.

“Have you ever engaged in prostitution? If so, how were you introduced to it?” reads the fifth of six questions. The rest of the queries involve employment, boyfriends, and criminal pasts. Meekins is cognizant of the link between women being involved with trafficking rings, romantic entanglements, sketchy job histories, and earlier convictions for crimes other than prostitution.

His mission is gaining traction. The Inspector General of Florida, Melinda M. Miguel, has recently worked with Meekins through the month of April to investigate the three female prisons in the state and come up with a program to train officers in human trafficking and address the prevalence of recruitment operations and overlooked victims within the facilities.

Survivors themselves, like Dellaca-Hedrick in Indiana and Alles in Florida have been important in driving the change in response. Tajuan McCarty, another human trafficking survivor, founded WellHouse in Alabama for victims of trafficking. She was arrested “more times than she can even remember” during her 10 years of being trafficked. Not once, she said, was she ever asked how she accumulated more than ten prostitution arrests, nor was she screened for trafficking.

“I kept getting arrested for prostitution, but that’s not what it was,” McCarty said. “I was under the control of a trafficker. But the officers didn’t care, they didn’t ask. I was just another prostitute in there, and was treated as such.”

Eventually she escaped her trafficker, went back to school, and opened a safe house for other exploited women, who, she said, also received prostitution records in place of investigations when they came into contact with officers. However, if victims are fortunate enough to escape the control of a trafficker, prostitution arrests can make their rehabilitation process and assimilation back into society incredibly difficult.

Brent Woody, a Florida State University Law School graduate, has taken it upon himself to help rehabilitate victims and get their haunting criminal records expunged. “If they can get those records expunged,” Woody said, “it opens a whole new world for them to be able to get funding and scholarships and help they need to start a new life, because they’re not criminals, they’re victims.”

In 2013, Woody worked with a state legislative team to pass a statute that allows this expungement if the women can prove at trial that they were under a trafficker’s control at the time of their arrest. Woody helps the women to collect the official documentation of their cases which matches federal human trafficking definition standards. Since the legislation became state law three years ago, he has been successful in all 12 cases he has taken on.

This Florida expungement law followed legislation first passed by New York in 2010 that allowed for the sealing victims’ records. Fifteen other states followed, forcing courts to seriously consider that trafficking might be behind some prostitution cases. Currently, 27 states also have vacature laws in place, which offer women some kind of restitution if they can prove that they were trafficked. They too can have their records sealed or cleared.

Former Chief State Judge of New York, Jonathan Lippman, started one of the first task forces in the country dedicated to helping trafficking victims who had been wrongly convicted of prostitution. It is made up of “judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, members of law enforcement, legislators, executive branch officials, forensic experts, victim’s advocates and legal scholars” its website says.

Lippman also opened Human Trafficking Courts in the state, providing women charged with prostitution with a place to have their arraignments held where there was an option other than plea or go to trial. In these new courts, women would automatically be considered for a six month rehabilitation program. If they have no further incidents, the charges could be dropped.

“The focus should be on the demand, on the traffickers and the buyers,” Lippman said in a 2014 New York Times article. “The reality is we don’t make decisions as to who gets arrested, and we want to assure that these victims get the assistance that they need and ultimately get out of ‘the life.’”

To manage the women brought into these courts, Lippman, in 2009, appointed Leigh Latimer to be in charge of the defense of women charged with prostitution. At the time, Latimer had spent more than 20 years working for the Legal Aid Society in New York, aiding and defending those who could not afford legal representation. Although she worked heavily with those faced with drug charges, she always held a special place in her heart for women charged with prostitution. She had noticed throughout her career that these women seemed generally to have been subjected to some kind of abuse or exploitation.

Although not all of her clients were necessarily victims of sex trafficking, the opening of the Human Trafficking Courts combined with human trafficking training —which the Legal Aid Society now offers to others, including law enforcement, judges and lawyers— helped her better understand how victims of human trafficking ended up with prostitution charges. Through a long and grueling process that can take up to two years to complete, she has helped dozens of victims get their records sealed.

The Legal Aid Society is not obligated to screen for trafficking in those it represents, but if trafficking is detected, the lawyers are trained to respond appropriately and lead victims to necessary services. “If clients do disclose trafficking, then there may be other levels of work we can do with them,” Latimer said. Although they treat every client the same, if trafficking is suspected and confirmed, the lawyers know how to converse and seek medical and psychological care for them, unlike many other professionals that come into contact with victims.