The Contraband Crisis

The inability of the arts and antiquities community to combat the crisis of looting by ISIS in the Middle East

by Marina Zheng

Photograph by Kelly Lowery/U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement

Not until Nina Burleigh was ready to leave did she make sense of all the mysterious comings and goings from the luxurious Tel Aviv apartment of Shlomo Moussaieff during their six hour interview. Moussaieff was well known for the fortune he had amassed as an international dealer in Holy Land relics and religious antiquities. His natural scowl and signature dark-framed glasses added to that mystique. But all that passing back and forth of wrapped packages and the hushed conversations in Hebrew left Burleigh baffled.

It wasn’t until she was briefly alone with one of his visitors, a Brooklyn native who spoke perfect English, did the journalist get a better idea of what she had witnessed. Burleigh learned that the woman had come to sell the dealer something “very special.” The package she brought and unwrapped for her held an exquisite Aramaic incantation bowl, a delicate museum piece that Burleigh quickly realized had almost certainly been looted from Iraq.

The journey of the incantation bowl is one that countless antiquities and art objects have made over the millennia. In the 20th century, the Germans sold “degenerate” or modern art to fund their country’s war effort. The genocidal Khmer Rouge plundered Cambodia’s terrains. African warlords still sell “blood diamonds” to fund insurgency.

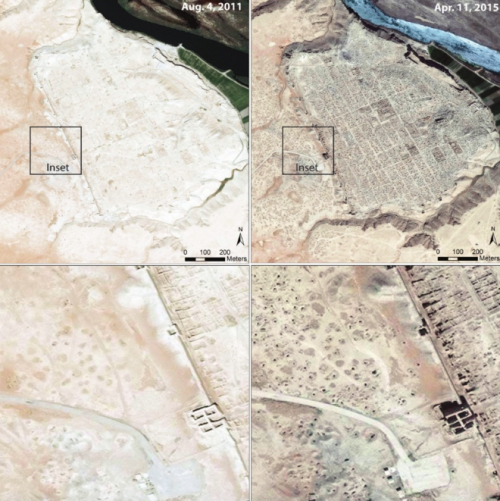

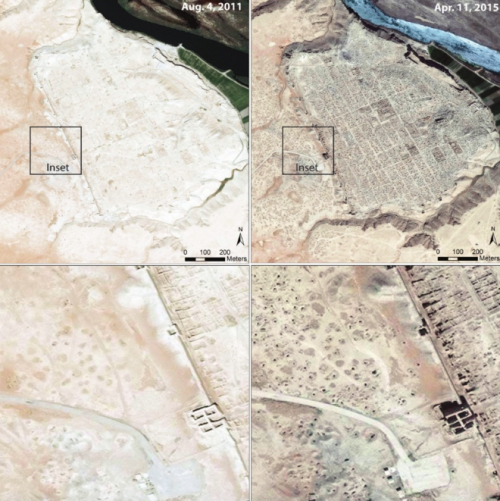

But over the past decade, looting in the Middle East has risen to crisis proportions, dramatically heightened by the recent involvement of ISIS in the illegal excavation and selling of ancient objects. Jesse Casana, a professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College, has methodically compiled and compared satellite images that document the extent of the looting. For data from 2007 onwards, he relied on images supplied by Digital Globe and those from as far back as the 1960s came from a CIA-operated CORONA satellite. He examined some 1,300 Syrian archaeological sites and included his research in a special issue of Near Eastern Archaeology, an academic journal published by the American School of Oriental Research.

Casana’s research disclosed that looting in Syria has been at the hands of both ISIS and the opposition forces. But the practice has been almost twice as extensive in ISIS controlled areas. Casana classifies the looting as severe in 22.9 percent of the territories under the Syrian regime’s control, a figure that goes up to 42.7 percent in ISIS-controlled areas. Moreover, the practice has been far more destructive under ISIS, which has been far cruder and more heavy-handed in its excavation methods. Since the war began in 2012, a fifth of all 15,000 archaeological sites in Syria have been plundered.

Dura Europos, eastern Syria, appearing on imagery from August 2011 and April 2015. In a closeup around the Palmyrene Gate, dozens of decades-old looting holes are visible (bottom left). Since 2014, the entire site has been severely looted with fresh looting holes clearly visible in the same area. Imagery © Digital Globe 2015.

The crisis prompted two journalists and a group of eight professors specializing in subjects such as archeology, law, and Near Eastern studies to gather for a conference at Wellesley College on September 24, 2015. Burleigh, a national political reporter for Newsweek, was among the first to speak. As a child, her playground was close to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Nearby sits Assyrian winged bulls that the university excavated in Iraq in 1929 and brought to the United States. Burleigh’s Assyrian grandmother was similarly displaced, forced to flee her home country of Iran when the Turks invaded. At just eight years old, she became a refugee who never saw her parents again. And with her two older sisters, she had to bury a baby brother on the road to safety.

For Burleigh, it was all personal, but others at the conference had a less emotional response. Salam al-Kuntar, an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, began her presentation with a tribute to the 700 Muslims worshippers who had been killed during a stampede in Mecca the day before.

“It is quite sad but among all sadness in the Middle East…” she trailed off with a defeated laugh. Al-Kuntar was struck by how little funding has gone into documenting the looting crisis or trying to find a solution. She might have a point. The FBI, for example, has only 16 agents on its art crime squad. These members also double as bomb duty watchmen, a job title that has little relationship to arts and antiquities. And in the city of London, which has one of the largest art markets in the world, the Art and Antiquities Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service recently experienced a budget cut that brought down its annual funding to the low hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Al-Kuntar told a story about her own experience in 2001, when she helped to set up a museum in the Syrian city of Deir Attya. In 2013, the Iraqi government retrieved memory sticks from an ISIS military base that contained images of looted items stolen from the same museum, estimating the value of the contraband at $500,000. But al-Kuntar said the figure was overblown; she knew for a fact that most of the items in the museum were replicas. “The patchy data that I have,” she said of the information given to her by the people in the region, “it’s inconsistent.”

Morag Kersel is in the business of monitoring and assessing the antiquities trade, specifically the looting of archeological sites. She is a professor at DePaul University in Chicago. “Demand is the driver of destruction,” she repeated over and over again during her presentation at the conference.

“I firmly believe that there would quite certainly be less looting if people and institutions did not want to own any undocumented pieces of the Middle Eastern past. So as an archeologist, in an ideal world, of course, I would like to see no looting, no selling, no buying of antiquities.”

Kersel used the term “acquisition apologetics” to describe the practice of collectors and curators who justify their questionable purchases with excuses such as, they were collecting dust in a private collection, or, we would never have discovered them otherwise. She proposed a strong solution: shame collectors so they will not buy undocumented artifacts, or better yet, stop buying artifacts altogether.

Hugh Eakins, a senior editor at the New York Review of Books, sat among the suit-clad panelists in his running sneakers and oversized olive green khakis. “I want to begin with a fairytale,” Eakins said. “It’s a story by Hans Christian Anderson. Maybe some of you know it. It’s called ‘The Most Incredible Thing.’”

Once upon a time, there was a contest in which the man who could create the most incredible thing would win the kingdom and the hand of the princess. For the competition, a gifted artist designed the world’s most magnificent clock. At the sight of the masterpiece, the people and judges unanimously agreed that the artist deserved the prizes. But suddenly, a man took an ax and dumbfounded the judges by walking through the crowd to the clock and smashing it to pieces. Demolishing a work of art like that? His action stunned the judges and instead of rewarding the artist, they declared the destroyer the winner.

“I did want to leave you with a more uplifting thought,” Eakins said. Just as the forced wedding was about to take place, the parts of the broken timepiece magically marched back into the hall and reassembled themselves into the beautiful clock. That, in turn, left the destroyer in defeat and the prize went back to the clockmaker.

“The spirit of art can’t be destroyed,” Eakins said. “Recognizing our conceptual difficulty with ISIS and with Syria, we really need to concentrate our attention and all of our resources on what can be done, what can be saved, and who can be saved.”

For all the back-and-forth at the conference, possible solutions were few. Every suggestion was countered. There was no consensus. “I don’t want to actually validate the atrocities that ISIS commits by speaking about them publicly,” said Clemens Reichel, a professor of Near & Middle Eastern civilizations at the University of Toronto, “And yet at the same time, can we just walk away from it? I don’t have the answer.”

Al-Kuntar picked up on the theme of the media’s role. Should academics disseminate their knowledge by cooperating with journalists? “Well, let’s ask the journalists here,” she said, directing her attention to Burleigh. “In covering ISIS and destruction, what are you looking for? What is the message you want to send out?” Burleigh responded, “Well, we’re not the ones who determine the message. We just ask the questions and take the information.”

“Yeah, but like—” al-Kuntar started to respond before Burleigh cut in. Academics, she said, should take a cautious approach when speaking to journalists. Burleigh stressed the importance of setting ground rules and establishing open communication.

At that moment, Patty Gerstenblith, a law professor at DePaul, interjected to disagree. Journalists, she said, are “coming in with an agenda.” Burleigh shot back. “I wouldn’t say they’re coming in with an agenda, but more like they want to know the facts.”

“Well,” said Gerstenblith, “they only want one answer for the fact.” During a recent interview with a journalist, the professor was asked to provide a statistic. When she tried to explain to the reporter that the question he asked could not be summed up by a number, he lost interest in the exchange.

The conference attempted to address another important question. Should the academics show images of looting and destruction by ISIS in classrooms? Should they use this “pornography of violence” in their teaching?

Jeremy Hutton responded in favor. He is a professor of Hebrew and Semitic Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “I consider myself an educator, that’s my job,” he said. “I am here to teach people, that is what I do. I’m not opposed to using still shots that show their destruction because this is educational.”

“But for what goal? To stir debate? To do what?” Charles E. Jones of Penn State University asked in outrage.

An audience member, middle-aged in a leather biker jacket with a mane of long wild hair, screamed from the back row: “We want people to call the senators!”

“To do what?” asked Jones.

“To begin to start the process of stopping looted materials from entering America,” the man said. “How do you stir people to political action? By not showing them images?”

The panel’s moderator was Guy Rogers, a professor of history and classics at Wellesley. He remained quiet through most of the day’s discussion, but in those last few minutes, he rose to pose a thought that summarized the conference, and perhaps the crisis as a whole.

“Most of what I’ve heard, quite frankly, has been quite defensive,” he said. “But if anybody has any more, slightly more proactive, aggressive, and likely-to-be-effective way of stopping people from doing these things, I’d like to hear them.”

A minute of silence passed as the panelists looked to each other with a sense of frustration-tinged helplessness. Finally, Hutton uttered three last words that spoke for everyone.

“I have nothing.”

The antiquities crisis can be traced back to 2014, when ISIS gained control of territories that Syrians had already been excavating, albeit on a more modest scale. Amr al-Azm, a professor of Middle East history and anthropology at Shawnee State University, explains that the terrorist group began licensing the looting to civilians and requesting a 20 percent cut of profits on all excavated objects. The situation soon escalated; over the summer of 2014, ISIS began to provide manpower and equipment to accelerate the looting. The more support they made available, the more money they could pocket. The group can claim up to 90 percent of the profit given that they provide all the resources.

After an excavation, al-Azm explained, there is a grace period for the looter to sell the objects and remit to ISIS its lion’s share. If the individual fails to do so, ISIS claims the right to confiscate the items and sell them, either at auctions which are often held in the Syrian city of Raqqa, or through middlemen who contact buyers via social media platforms.

Al-Azm has received many of these messages on the popular instant messaging service WhatsApp. His affiliation is a result of his research, which focuses on tracking artifacts from conflict region to determine whether they’ve been stolen from a museum or looted right out of the ground. He said that getting in touch with a seller is no more difficulty than visiting the old markets of southern Turkey.

“Everybody knows somebody on the inside who is involved in looting and somebody on the outside who acts as a middlemen,”

al-Azm said. “I don’t usually respond. If I were to be involved in a negotiation, then yes I would. But there would be a specific reason why I would be doing that.” For example, he might do so for the sake of tracking an object.

The asking prices of looted objects can range from $5 to roughly $250,000 with room for negotiation. Of all the messages that al-Azm has received, one of the most impressive featured a set of mosaics that had an estimated value of anywhere from $10,000 to $50,000.

Exactly how much is ISIS profiting from the looting of antiquities? “A bloody amount,” al-Azm said. “We can say that looted antiquities form an important source of revenue for them. It’s not just organized, it’s institutionalized.”

Looting sponsored by ISIS falls under what the group calls its Department of Precious Things That Come Out of the Ground, or Diwan al-Rikaz in Arabic. This classifies antiquities with oil, another source of revenue and control for the terrorist group. While experts do not have reliable data as to how much ISIS has amassed from its antiquities operations, a New Yorker article noted collection of at least $265,00 for a six months period in 2015.

In 2011, U.S. customs officials in Memphis seized a shipment of 200 to 300 small clay tablets and began investigating this alleged illicit importation of cultural heritage from Iraq. The artifacts had arrived from Israel and were slated for display at the Museum of the Bible, set to open in Washington, D.C. in 2017. The Green family, which owns the Hobby Lobby craft stores chain, is funding the new museum.The family is known for both its fundamentalist Christian values and its substantial art collection. The case epitomizes the fear that archaeologists, art historians, and experts in the antiquities field have that looted artifacts from Syria or Iraq are ending up on U.S. soil.

It also points up the conflict between the various stakeholders in the arts and antiquities communities. Archeologists and museum curators, for example, disagree over the ethics and propriety of acquiring antiquities from conflict zones. Archaeologists stress that there should be no market for these artifacts; curators emphasize the need to protect these precious objects from possible destruction.

As Bruce Altshuler of New York University enumerated the various vantage points: “Historians and archeologists care about [the] scientific record,” he said. “People in the source countries care about heritage. People at museums might care about [the artifacts] as aesthetic objects. So there are different kinds of interests involved.”

As a professor of museum studies, he loyally sides with the museums. From his perspective, the circulation of art objects is vital to the growth and development of these important public institutions. “Well, what are the alternatives here?” he asked matter-of-factly. “Demand is necessary for museums to function. Museums don’t exist apart from that world; that is how things get into museums.”

Others, however, disagree with the notion that these objects are better off sitting in glass display boxes or hanging on well-guarded walls. Stephennie Mulder is a professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. She first became enamored of the subject in a class on Islamic civilization taught by the historian Peter von Sivers in her undergraduate days at the University of Utah. “There was this sense that this incredible, rich world—which had not been a part of my education at all—opened up,” she said with a faint smile, her blue eyes lighting up at the thought. “There was this whole universe of an incredible, opulent, imperial world that I had never learned about.”

Discussing the current crisis takes Mulder back to the 12 years she spent in Syria as an archeologist. For her and many colleagues who have had intimate connections with the civilians living in these war-torn regions, it is difficult to separate out their personal responses to the human strife. “I don’t think I separate my professional side from my personal side very well. I really care about that place and the thing that really gets to you…” she trailed off. “Yes, Syria was—and I hope it still is—a stunningly beautiful place with this rich world of antiquities.” In the end, she said, it is really the people of Syria who capture the heart. “You have to remember that the collection and sale of these objects literally have a cost in human lives,”she said. “Putting them in these museums settings sometimes make it difficult to remember that these objects have contexts and histories that are linked to real people.”

The crisis almost cost Jennifer Udell her job as the official curator of the arts at Fordham University. In the early days of January, 2014, she was largely responsible for the university’s acquisition of nine rare Syrian mosaics from a church built in the fifth century. Udell was featured in a short university magazine article about the purchase.

“Well-meaning friends put that story on Facebook, saying ‘look at what we got, yay!’” Udell said, gesturing dramatically with her hands. “And then not-so-well-meaning friends of well-meaning friends piled on, and immediately started screaming ‘provenance, provenance, provenance.’”

She found the response ridiculous. “First thing you should know is that I was waiting at the tarmac at JFK with a fist full of dollars and waiting for all the conflict antiquities to come out of Syria,” Udell sarcastically joked. “Okay, that’s not what happened.”

The university had, in fact, acquired the artifacts legally in Beirut, where they had been kept since 1972. Fordham’s due diligence determined that their likely point of origin was Syria. As for provenance, she said they came with “paperwork that can only be described as rare and enviable in the world of collecting antiquities.”

Jennifer Udell, photographed with her colleague Dr. Michael Peppard, was largely responsible for the acquisition of nine Syrian mosaics dating back to the fifth century. Imagery © Inside Fordham

“Now I don’t know what 1972 has to do with 2014,” she added, “except that people who are looking for a problem will try to make these huge leaps.”

After the kerfuffle over the article, Udell was on her way upstate for a short trip. That Friday, she checked her email one last time before she took off. There were two messages in her inbox: one from an investigative journalist named Jason Felch and the other from David Gill, an archaeologist. Both challenged her role in the university’s acquisition of the mosaics.

There was nothing relaxing about the weekend. Udell spent it crafting a statement and providing all the background information she had about the mosaics, aside from the name of the donor, who had requested to remain anonymous. On Monday morning, she sent the statement to both men. Gill responded dismissively but Felch challenged her further with words to the effect of: Dear Jennifer, thank you so much! Your transparency is going to go a long way in dispelling the critic, but the devil is in the details. For instance, why does the donor want to remain anonymous?

Felch’s persistence stems from the abundance of false ownership histories and bogus paper trails he encountered while reporting about looted antiquities. “One of the things I do and I think museums and auction houses and everybody else should do is come at these provenance stories with a skeptical eye,” Felch said. “So what I was doing with Fordham was saying, ‘Have you guys run these down?’”

Months go by and the university continues to ignore Felch’s request for more documents, prompting him to wonder why, especially since Udell told him that the university had done its due diligence before agreeing to the acquisition. “There are two main points here; one is did ‘they do the research’ and two is ‘are they transparent about it?’” Felch said. “As a university in particular, I feel like they have an obligation to be.”

In the meantime, Felch posted more on his well-known blog “Chasing Aphrodite” to publicly raise questions about the mosaic’s origins. The former Los Angeles Times reporter, who was fired from the newspaper for having an “inappropriate relationship” with a confidential source, is also the author of Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum. The book was a 2006 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting. For Udell, it was exasperating. “I tried to play fair with him, I was really transparent,” she said. “What did he do? He turned tail.”

At the U.S. federal level, there is action. Last summer, Sen. Robert Casey Jr., a Pennsylvania Democrat, along with two Republican senators, Chuck Grassley of Iowa and David Perdue of Georgia, introduced the “Protect and Preserve International Cultural Property Act” bill as an attempt to address the problem from the homefront.

In April, the bill was unanimously voted in by the Senate after passing through the House of Representatives in June of 2015. Now, it awaits the president’s signature. If signed, the bill will impose an import ban on all Syrian antiquities removed from the Middle Eastern country after March of 2011. It will also enable the president to put at-risk objects in U.S. custody as temporary shelter.

The concept of safekeeping has also been endorsed by the Association of Art Museum Directors, who outlined the organization’s position in its October 2015 Protocols for Safe Havens for Works of Cultural Significance from Countries in Crisis. Under this framework, foreign owners of at-risk items can request the artifacts’ temporary safekeeping at various international museums.

The new document supersedes an earlier protocol, passed June 2008, and changes the organization’s position on ownership. While the older document affirms permanent acquisition by museums, the newer one uses the language of temporary safekeeping by promising the return of artifacts to their countries of origin. “The timing of the return of works will depend on the circumstances existing in the country from which the works were removed, but if possible should be effected as soon as practical after the situation giving rise to the need for a safe haven has passed,” the protocol states.

Anita Difanis, who handles government affairs for the group, said the association has shared the protocols widely throughout the international museum community in hopes of sparking conversation, especially at museums in the crisis area. Indeed, many legal experts think that little can be done by the United States, considering its distance from the epicenter of the crisis.

James McAndrew sits in his law office at GDLSK LLP on the 25th floor of a Park Avenue high rise. Diplomas and certificates line his walls while photographs of his children line his desk. Back in 1988, he was a special agent at U.S. Customs and Border Protection. McAndrew explained that at the time, there was only one agent in the entire country who had the responsibility of conducting investigations in the art and antiquities world– too few to do significant work in an area wrought with unregulation.

McAndrews understood how easily art could be used to launder money. “You can buy a $100 million Picasso painting, take it out of the frame, fold it in half, stick it inside your New York TImes newspaper, go through TSA, hand your newspaper to the TSA agent as you walk through the metal detector, and then come out the other side as the TSA guy gives back your newspaper,” McAndrew said. “Of course, $100 million of illicit proceeds.”

He developed the International Art Theft Program for Homeland Security. Over the course of 10 years, he trained some 400 agents in how to detect stolen works of art and arrange for their return to the rightful source countries.

“As I was being aggressive and training the agents to be aggressive in what to look for, I realized that there was no mechanisms or procedures in place for the collectors and dealers, auction houses, and museums to now respond to the mass amount of cultural claims,” McAndrew said. “So I felt like it got a little out of control with the government and I thought that it wasn’t what I was espousing as the person responsible for the training.”

The realization prompted McAndrews to enter private practice, where he is defending institutions that own disputed art. Having experienced both sides of the game, McAndrew is well versed in the powers and limitations of U.S. legal efforts. And in his opinion, none of them can combat the crisis of looting in the Middle East. These proposals are merely political soundbites, he said. While creating the impression that lawmakers are being proactive, they have little authority in these matters.

“We can pass all the resolutions in the world but there is nothing we can do,” he said. “The people that need to respond and lead are the countries in the region, the ones that surround Syria and Iraq.” In other words, since objects looted by ISIS are likely to pass through multiple countries before they ever—if ever—end up in the United States, it is critical for the countries that are closest to the conflict to take extra precautions to stop the illicit trade. McAndrews pointed to Lebanon and Cyprus as key places where a given work might “cool off.” “And then all of a sudden, three years later, it shows up in a shipment from Dubai or from Hong Kong into the U.S. and nothing on it says, ‘Oh by the way, I was just dug out of the ground in Iraq.’”

A solution, McAndrew said, could be the 1983 convention on the Cultural Property Implementation Act, which President Ronald Reagan signed into law. It clearly states that any source country which has undertaken internal measures to address the problem can request that the United States impose import restrictions on any of its archeological objects that have been looted and traded abroad. The idea is that both parties must put in equal effort; the responsibility cannot be solely that of the United States. “Now if Israel or Iran, for example, want to just close their eyes and say ‘I’m not doing anything,’ then we need to punish them [and] sanction those countries,” McAndrew said.

Technology might also offer a way forward. Palmyra once stood as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, housing some of the best-preserved temples in the region. Ever since ISIS took over the Syrian city and began the systematic destruction of its heritage sites, independent cultural organizations have been creating three-dimensional digital models of the destroyed monuments. The Arch of Triumph, a secular structure that was demolished by ISIS in October of 2015, has been digitally recreated in London’s Trafalgar Square. The replica weighs 11 tons and is 20 feet tall, which is two-thirds of the arch’s original size. Plans for installing such digital models at tourists sites in New York City are also in the works and news of the ISIS retreat from Palmyra in late March has given rise to thoughts of using the same technology to produce a replica of how the whole city once looked.

A replica of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph has been temporarily recreated at Trafalgar Square in London. Image © Getty

While looters use the web as a marketplace for stolen antiquities, protectors of cultural heritage find it equally accommodating. International law enforcement agencies have set up online databases of looted items. The FBI’s database lists 15,000 objects and INTERPOL’s contains 48,000. This enables dealers and buyers to identify unauthorized items.

The Institute for Digital Archeology, a joint venture between Harvard University, Oxford University, and Dubai’s Museum of the Future, attempts to combine archeology with technology. Its Million Image Database Project has developed an inexpensive and easy-to-use three-dimensional camera with automated GPS stamping capacity. Volunteers take these cameras to UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger and are tasked with taking pictures of the artifacts at those sites, in case they are looted in the future. These images are then sent back to the institute’s headquarters at Oxford

The photographs are stamped with a time and location that help track the movement of a given item. When one appears on the market, the images can be consulted to locate its excavation spot and approximate when it was looted. Some 1,000 cameras are in the field and to date, some 200,000 images have been scanned. By the end of the year, the institute hopes to have 5,000 cameras in circulation and a million images added to its database.

The barriers to effective response are manifold. To start with, the United States has broken diplomatic relations with Syria. The issue of looting in the Middle East is simply out of U.S. jurisdiction. The various proposals and resolutions that have been put forth by the United States or the United Nations do not carry the force of law. Although in August of 2015, the FBI posted an official statement advising prospective buyers to avoid purchasing undocumented artifacts from the Middle East, it was a warning and not a law. In February of 2015, the U.N. Security Council passed “Resolution 2199” as a call for the collective effort to stop the illegal trade of antiquities from conflict regions in the Middle East. But it stands as only a non-binding agreement among its signatories.

The sheer volatility of the region is a restriction in itself.

“Overcoming those dangers is huge in a place like Syria right now. It’s almost unfathomable how anything could come out, even the people can’t get out,”

said Anita Difanis of the AAMD. “So while [ISIS is] bombing cities and communities, it’s pretty hard to go in and do anything organized.”

In the early stages of the Syrian civil war, a group of 200 archeologists who called themselves the Monuments Men travelled unarmed through rebel territory with a shared mission to save ancient artifacts in Syria. The name is a reference to the historians, professors, and curators who protected artwork from Nazi looting during World War II, memorialized in a recent Hollywood film. But since the group’s formation four years ago, ISIS has killed 15 of the monuments men, one, 82-year-old Khaled al-Asaad, was the former general manager of Palmyra’s antiquities and museums. He was beheaded for refusing to reveal the locations of archeological objects.

Another hurdle is perhaps more conceptual and less obvious than the first: the issue of defining provenance in light of the current looting crisis. McAndrews explained its significance. “‘Provenance’ now becomes a real word,” he said. “Now I’ll say, define provenance. What’s acceptable provenance to you versus you, you, and you? And no one has a consistent answer. That’s a problem.”

In today’s art market, only 25 percent of the objects have undisputed provenance. As for the rest, nobody can say for certain where the pieces originate. McAndrew stated that this is also a result of shifting national borders over time. “Because the Ottoman Empire, when they defeated the Romans, are in this area. And the Babylonians go here,” McAndrew said, grabbing a piece of scrap paper from his folder and drawing out a rough sketch of the region. “And then they crossed and they didn’t have today’s modern-day boundaries. That’s a very key issue and it’s no one’s fault.”

A new report released by the National Center for Policy Analysis in January estimates that since 2013, ISIS has earned $36 million to $360 million from selling looted antiquities. To put into perspective just how much damage can be done with even this low estimate of $36 million, the report states that a terrorist attack on par with 9/11 only costs $400,000 to $500,000 to execute.

David Grantham, the author of the study and a senior fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis, argues that authorities need to realize the definite link between terrorism and illegal antiquities. He cites Al-Qaeda as another terrorist group that tried to use profits from the antiquities trade to fund its activities. In 1999, Mohamed Atta attempted to sell Afghan objects to a German university professor. He “claimed that he was selling artifacts to purchase an airplane.” Just two years later, Atta piloted a Boeing 767 into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

“I think the military and the government can take a stronger action going into an area of conflict and we can probably do more there,” Grantham said, citing U.S. troops in Iraq as an example. “Assuming it’s coming from areas like Syria, where we don’t have troops on the ground per se, it becomes more cooperative.”

Antiquities organizations take a similar stance. In April, the Antiquities Coalition, the Middle East Institute, and the Asia Society created a task force report titled #CultureUnderThreat that demands military action by the White House.

“U.S. armed forces and their coalition partners should engage in military air strikes, as appropriated, against targets threatening known heritage sites as part of their comprehensive mission to defeat violent extremism,” the report said.

Grantham was a soldier himself in the mid-2000s. He was deployed to Afghanistan in 2006 and Iraq in 2008 on what he jokingly called an “all-expense-paid trip.” It was during his time as a Special Agent with the Air Force Office of Special Investigations that he had the opportunity to have prolonged interaction with Afghani and Iraqi locals and develop an appreciation for their cultures. It led him to study Arabic in Austin on his return to the United States.

On a fundamental level, how many people not involved in the issue understand the importance of cultural heritage and the need to protect it? For archaeologists, museum curators, and other experts in the field, providing an incentive for more people to care is first and foremost in finding a solution to the looting crisis. The task will not be an easy one judging by the attendance at the Wellesley conference in September. Only 20 people sat in an auditorium that can hold hundreds.

Disillusion and frustration permeated the space at the end of that day-long panel discussion. No conclusions were reached, no solutions were provided. The speakers could not seem to agree with one another and the audience members seemed unsure of whose opinions to take most seriously. Stephennie Mulder was one of the last to leave the auditorium. The UT-Austin professor stayed behind to chat with some of the students who attended the conference.

“By the way, not all academic conferences are like that,” she joked, referring to the heated debates that had occurred towards the end of the day. “Many are boring.”

As an archeologist and a scholar, Mulder believes her job is “to craft a narrative and raise a new generation of young people—and also of people who are already [my age] and older—to begin to shift consciousness on the significance of heritage in general.” She thinks that being well informed helps spark the incentive to care. The Temple of Bel in Palmyra, she said, is a perfect example. In August of 2015, ISIS blew up the structure, which has been standing since 32 A.D. Mulder explained that the parthenon-sized structure was considered to be of equivalent beauty and importance to its Greek counterpart.

The Temple of Bel before its destruction in August, 2015.

“But I wonder how many people have heard of the Temple of Bel before it was destroyed,” Mulder said. “If the Parthenon stands for the birth of democracy, the Temple of Bel stands for the kind of multi-cultural society that we all want to be a part of. And that idea was lost with the building, but how many people knew that?”

Photograph by Kelly Lowery/U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement

Not until Nina Burleigh was ready to leave did she make sense of all the mysterious comings and goings from the luxurious Tel Aviv apartment of Shlomo Moussaieff during their six hour interview. Moussaieff was well known for the fortune he had amassed as an international dealer in Holy Land relics and religious antiquities. His natural scowl and signature dark-framed glasses added to that mystique. But all that passing back and forth of wrapped packages and the hushed conversations in Hebrew left Burleigh baffled.

It wasn’t until she was briefly alone with one of his visitors, a Brooklyn native who spoke perfect English, did the journalist get a better idea of what she had witnessed. Burleigh learned that the woman had come to sell the dealer something “very special.” The package she brought and unwrapped for her held an exquisite Aramaic incantation bowl, a delicate museum piece that Burleigh quickly realized had almost certainly been looted from Iraq.

The journey of the incantation bowl is one that countless antiquities and art objects have made over the millennia. In the 20th century, the Germans sold “degenerate” or modern art to fund their country’s war effort. The genocidal Khmer Rouge plundered Cambodia’s terrains. African warlords still sell “blood diamonds” to fund insurgency.

But over the past decade, looting in the Middle East has risen to crisis proportions, dramatically heightened by the recent involvement of ISIS in the illegal excavation and selling of ancient objects. Jesse Casana, a professor of anthropology at Dartmouth College, has methodically compiled and compared satellite images that document the extent of the looting. For data from 2007 onwards, he relied on images supplied by Digital Globe and those from as far back as the 1960s came from a CIA-operated CORONA satellite. He examined some 1,300 Syrian archaeological sites and included his research in a special issue of Near Eastern Archaeology, an academic journal published by the American School of Oriental Research.

Casana’s research disclosed that looting in Syria has been at the hands of both ISIS and the opposition forces. But the practice has been almost twice as extensive in ISIS controlled areas. Casana classifies the looting as severe in 22.9 percent of the territories under the Syrian regime’s control, a figure that goes up to 42.7 percent in ISIS-controlled areas. Moreover, the practice has been far more destructive under ISIS, which has been far cruder and more heavy-handed in its excavation methods. Since the war began in 2012, a fifth of all 15,000 archaeological sites in Syria have been plundered.

Dura Europos, eastern Syria, appearing on imagery from August 2011 and April 2015. In a closeup around the Palmyrene Gate, dozens of decades-old looting holes are visible (bottom left). Since 2014, the entire site has been severely looted with fresh looting holes clearly visible in the same area. Imagery © Digital Globe 2015.

The crisis prompted two journalists and a group of eight professors specializing in subjects such as archeology, law, and Near Eastern studies to gather for a conference at Wellesley College on September 24, 2015. Burleigh, a national political reporter for Newsweek, was among the first to speak. As a child, her playground was close to the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Nearby sits Assyrian winged bulls that the university excavated in Iraq in 1929 and brought to the United States. Burleigh’s Assyrian grandmother was similarly displaced, forced to flee her home country of Iran when the Turks invaded. At just eight years old, she became a refugee who never saw her parents again. And with her two older sisters, she had to bury a baby brother on the road to safety.

For Burleigh, it was all personal, but others at the conference had a less emotional response. Salam al-Kuntar, an anthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania, began her presentation with a tribute to the 700 Muslims worshippers who had been killed during a stampede in Mecca the day before.

“It is quite sad but among all sadness in the Middle East…” she trailed off with a defeated laugh. Al-Kuntar was struck by how little funding has gone into documenting the looting crisis or trying to find a solution. She might have a point. The FBI, for example, has only 16 agents on its art crime squad. These members also double as bomb duty watchmen, a job title that has little relationship to arts and antiquities. And in the city of London, which has one of the largest art markets in the world, the Art and Antiquities Unit of the Metropolitan Police Service recently experienced a budget cut that brought down its annual funding to the low hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Al-Kuntar told a story about her own experience in 2001, when she helped to set up a museum in the Syrian city of Deir Attya. In 2013, the Iraqi government retrieved memory sticks from an ISIS military base that contained images of looted items stolen from the same museum, estimating the value of the contraband at $500,000. But al-Kuntar said the figure was overblown; she knew for a fact that most of the items in the museum were replicas. “The patchy data that I have,” she said of the information given to her by the people in the region, “it’s inconsistent.”

Morag Kersel is in the business of monitoring and assessing the antiquities trade, specifically the looting of archeological sites. She is a professor at DePaul University in Chicago. “Demand is the driver of destruction,” she repeated over and over again during her presentation at the conference.

“I firmly believe that there would quite certainly be less looting if people and institutions did not want to own any undocumented pieces of the Middle Eastern past. So as an archeologist, in an ideal world, of course, I would like to see no looting, no selling, no buying of antiquities.”

Kersel used the term “acquisition apologetics” to describe the practice of collectors and curators who justify their questionable purchases with excuses such as, they were collecting dust in a private collection, or, we would never have discovered them otherwise. She proposed a strong solution: shame collectors so they will not buy undocumented artifacts, or better yet, stop buying artifacts altogether.

Hugh Eakins, a senior editor at the New York Review of Books, sat among the suit-clad panelists in his running sneakers and oversized olive green khakis. “I want to begin with a fairytale,” Eakins said. “It’s a story by Hans Christian Anderson. Maybe some of you know it. It’s called ‘The Most Incredible Thing.’”

Once upon a time, there was a contest in which the man who could create the most incredible thing would win the kingdom and the hand of the princess. For the competition, a gifted artist designed the world’s most magnificent clock. At the sight of the masterpiece, the people and judges unanimously agreed that the artist deserved the prizes. But suddenly, a man took an ax and dumbfounded the judges by walking through the crowd to the clock and smashing it to pieces. Demolishing a work of art like that? His action stunned the judges and instead of rewarding the artist, they declared the destroyer the winner.

“I did want to leave you with a more uplifting thought,” Eakins said. Just as the forced wedding was about to take place, the parts of the broken timepiece magically marched back into the hall and reassembled themselves into the beautiful clock. That, in turn, left the destroyer in defeat and the prize went back to the clockmaker.

“The spirit of art can’t be destroyed,” Eakins said. “Recognizing our conceptual difficulty with ISIS and with Syria, we really need to concentrate our attention and all of our resources on what can be done, what can be saved, and who can be saved.”

For all the back-and-forth at the conference, possible solutions were few. Every suggestion was countered. There was no consensus. “I don’t want to actually validate the atrocities that ISIS commits by speaking about them publicly,” said Clemens Reichel, a professor of Near & Middle Eastern civilizations at the University of Toronto, “And yet at the same time, can we just walk away from it? I don’t have the answer.”

Al-Kuntar picked up on the theme of the media’s role. Should academics disseminate their knowledge by cooperating with journalists? “Well, let’s ask the journalists here,” she said, directing her attention to Burleigh. “In covering ISIS and destruction, what are you looking for? What is the message you want to send out?” Burleigh responded, “Well, we’re not the ones who determine the message. We just ask the questions and take the information.”

“Yeah, but like—” al-Kuntar started to respond before Burleigh cut in. Academics, she said, should take a cautious approach when speaking to journalists. Burleigh stressed the importance of setting ground rules and establishing open communication.

At that moment, Patty Gerstenblith, a law professor at DePaul, interjected to disagree. Journalists, she said, are “coming in with an agenda.” Burleigh shot back. “I wouldn’t say they’re coming in with an agenda, but more like they want to know the facts.”

“Well,” said Gerstenblith, “they only want one answer for the fact.” During a recent interview with a journalist, the professor was asked to provide a statistic. When she tried to explain to the reporter that the question he asked could not be summed up by a number, he lost interest in the exchange.

The conference attempted to address another important question. Should the academics show images of looting and destruction by ISIS in classrooms? Should they use this “pornography of violence” in their teaching?

Jeremy Hutton responded in favor. He is a professor of Hebrew and Semitic Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “I consider myself an educator, that’s my job,” he said. “I am here to teach people, that is what I do. I’m not opposed to using still shots that show their destruction because this is educational.”

“But for what goal? To stir debate? To do what?” Charles E. Jones of Penn State University asked in outrage.

An audience member, middle-aged in a leather biker jacket with a mane of long wild hair, screamed from the back row: “We want people to call the senators!”

“To do what?” asked Jones.

“To begin to start the process of stopping looted materials from entering America,” the man said. “How do you stir people to political action? By not showing them images?”

The panel’s moderator was Guy Rogers, a professor of history and classics at Wellesley. He remained quiet through most of the day’s discussion, but in those last few minutes, he rose to pose a thought that summarized the conference, and perhaps the crisis as a whole.

“Most of what I’ve heard, quite frankly, has been quite defensive,” he said. “But if anybody has any more, slightly more proactive, aggressive, and likely-to-be-effective way of stopping people from doing these things, I’d like to hear them.”

A minute of silence passed as the panelists looked to each other with a sense of frustration-tinged helplessness. Finally, Hutton uttered three last words that spoke for everyone.

“I have nothing.”

The antiquities crisis can be traced back to 2014, when ISIS gained control of territories that Syrians had already been excavating, albeit on a more modest scale. Amr al-Azm, a professor of Middle East history and anthropology at Shawnee State University, explains that the terrorist group began licensing the looting to civilians and requesting a 20 percent cut of profits on all excavated objects. The situation soon escalated; over the summer of 2014, ISIS began to provide manpower and equipment to accelerate the looting. The more support they made available, the more money they could pocket. The group can claim up to 90 percent of the profit given that they provide all the resources.

After an excavation, al-Azm explained, there is a grace period for the looter to sell the objects and remit to ISIS its lion’s share. If the individual fails to do so, ISIS claims the right to confiscate the items and sell them, either at auctions which are often held in the Syrian city of Raqqa, or through middlemen who contact buyers via social media platforms.

Al-Azm has received many of these messages on the popular instant messaging service WhatsApp. His affiliation is a result of his research, which focuses on tracking artifacts from conflict region to determine whether they’ve been stolen from a museum or looted right out of the ground. He said that getting in touch with a seller is no more difficulty than visiting the old markets of southern Turkey.

“Everybody knows somebody on the inside who is involved in looting and somebody on the outside who acts as a middlemen,”

al-Azm said. “I don’t usually respond. If I were to be involved in a negotiation, then yes I would. But there would be a specific reason why I would be doing that.” For example, he might do so for the sake of tracking an object.

The asking prices of looted objects can range from $5 to roughly $250,000 with room for negotiation. Of all the messages that al-Azm has received, one of the most impressive featured a set of mosaics that had an estimated value of anywhere from $10,000 to $50,000.

Exactly how much is ISIS profiting from the looting of antiquities? “A bloody amount,” al-Azm said. “We can say that looted antiquities form an important source of revenue for them. It’s not just organized, it’s institutionalized.”

Looting sponsored by ISIS falls under what the group calls its Department of Precious Things That Come Out of the Ground, or Diwan al-Rikaz in Arabic. This classifies antiquities with oil, another source of revenue and control for the terrorist group. While experts do not have reliable data as to how much ISIS has amassed from its antiquities operations, a New Yorker article noted collection of at least $265,00 for a six months period in 2015.

In 2011, U.S. customs officials in Memphis seized a shipment of 200 to 300 small clay tablets and began investigating this alleged illicit importation of cultural heritage from Iraq. The artifacts had arrived from Israel and were slated for display at the Museum of the Bible, set to open in Washington, D.C. in 2017. The Green family, which owns the Hobby Lobby craft stores chain, is funding the new museum.The family is known for both its fundamentalist Christian values and its substantial art collection. The case epitomizes the fear that archaeologists, art historians, and experts in the antiquities field have that looted artifacts from Syria or Iraq are ending up on U.S. soil.

It also points up the conflict between the various stakeholders in the arts and antiquities communities. Archeologists and museum curators, for example, disagree over the ethics and propriety of acquiring antiquities from conflict zones. Archaeologists stress that there should be no market for these artifacts; curators emphasize the need to protect these precious objects from possible destruction.

As Bruce Altshuler of New York University enumerated the various vantage points: “Historians and archeologists care about [the] scientific record,” he said. “People in the source countries care about heritage. People at museums might care about [the artifacts] as aesthetic objects. So there are different kinds of interests involved.”

As a professor of museum studies, he loyally sides with the museums. From his perspective, the circulation of art objects is vital to the growth and development of these important public institutions. “Well, what are the alternatives here?” he asked matter-of-factly. “Demand is necessary for museums to function. Museums don’t exist apart from that world; that is how things get into museums.”

Others, however, disagree with the notion that these objects are better off sitting in glass display boxes or hanging on well-guarded walls. Stephennie Mulder is a professor of Islamic art and architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. She first became enamored of the subject in a class on Islamic civilization taught by the historian Peter von Sivers in her undergraduate days at the University of Utah. “There was this sense that this incredible, rich world—which had not been a part of my education at all—opened up,” she said with a faint smile, her blue eyes lighting up at the thought. “There was this whole universe of an incredible, opulent, imperial world that I had never learned about.”

Discussing the current crisis takes Mulder back to the 12 years she spent in Syria as an archeologist. For her and many colleagues who have had intimate connections with the civilians living in these war-torn regions, it is difficult to separate out their personal responses to the human strife. “I don’t think I separate my professional side from my personal side very well. I really care about that place and the thing that really gets to you…” she trailed off. “Yes, Syria was—and I hope it still is—a stunningly beautiful place with this rich world of antiquities.” In the end, she said, it is really the people of Syria who capture the heart. “You have to remember that the collection and sale of these objects literally have a cost in human lives,”she said. “Putting them in these museums settings sometimes make it difficult to remember that these objects have contexts and histories that are linked to real people.”

The crisis almost cost Jennifer Udell her job as the official curator of the arts at Fordham University. In the early days of January, 2014, she was largely responsible for the university’s acquisition of nine rare Syrian mosaics from a church built in the fifth century. Udell was featured in a short university magazine article about the purchase.

“Well-meaning friends put that story on Facebook, saying ‘look at what we got, yay!’” Udell said, gesturing dramatically with her hands. “And then not-so-well-meaning friends of well-meaning friends piled on, and immediately started screaming ‘provenance, provenance, provenance.’”

She found the response ridiculous. “First thing you should know is that I was waiting at the tarmac at JFK with a fist full of dollars and waiting for all the conflict antiquities to come out of Syria,” Udell sarcastically joked. “Okay, that’s not what happened.”

The university had, in fact, acquired the artifacts legally in Beirut, where they had been kept since 1972. Fordham’s due diligence determined that their likely point of origin was Syria. As for provenance, she said they came with “paperwork that can only be described as rare and enviable in the world of collecting antiquities.”

Jennifer Udell, photographed with her colleague Dr. Michael Peppard, was largely responsible for the acquisition of nine Syrian mosaics dating back to the fifth century. Imagery © Inside Fordham

“Now I don’t know what 1972 has to do with 2014,” she added, “except that people who are looking for a problem will try to make these huge leaps.”

After the kerfuffle over the article, Udell was on her way upstate for a short trip. That Friday, she checked her email one last time before she took off. There were two messages in her inbox: one from an investigative journalist named Jason Felch and the other from David Gill, an archaeologist. Both challenged her role in the university’s acquisition of the mosaics.

There was nothing relaxing about the weekend. Udell spent it crafting a statement and providing all the background information she had about the mosaics, aside from the name of the donor, who had requested to remain anonymous. On Monday morning, she sent the statement to both men. Gill responded dismissively but Felch challenged her further with words to the effect of: Dear Jennifer, thank you so much! Your transparency is going to go a long way in dispelling the critic, but the devil is in the details. For instance, why does the donor want to remain anonymous?

Felch’s persistence stems from the abundance of false ownership histories and bogus paper trails he encountered while reporting about looted antiquities. “One of the things I do and I think museums and auction houses and everybody else should do is come at these provenance stories with a skeptical eye,” Felch said. “So what I was doing with Fordham was saying, ‘Have you guys run these down?’”

Months go by and the university continues to ignore Felch’s request for more documents, prompting him to wonder why, especially since Udell told him that the university had done its due diligence before agreeing to the acquisition. “There are two main points here; one is did ‘they do the research’ and two is ‘are they transparent about it?’” Felch said. “As a university in particular, I feel like they have an obligation to be.”

In the meantime, Felch posted more on his well-known blog “Chasing Aphrodite” to publicly raise questions about the mosaic’s origins. The former Los Angeles Times reporter, who was fired from the newspaper for having an “inappropriate relationship” with a confidential source, is also the author of Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum. The book was a 2006 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Investigative Reporting. For Udell, it was exasperating. “I tried to play fair with him, I was really transparent,” she said. “What did he do? He turned tail.”

At the U.S. federal level, there is action. Last summer, Sen. Robert Casey Jr., a Pennsylvania Democrat, along with two Republican senators, Chuck Grassley of Iowa and David Perdue of Georgia, introduced the “Protect and Preserve International Cultural Property Act” bill as an attempt to address the problem from the homefront.

In April, the bill was unanimously voted in by the Senate after passing through the House of Representatives in June of 2015. Now, it awaits the president’s signature. If signed, the bill will impose an import ban on all Syrian antiquities removed from the Middle Eastern country after March of 2011. It will also enable the president to put at-risk objects in U.S. custody as temporary shelter.

The concept of safekeeping has also been endorsed by the Association of Art Museum Directors, who outlined the organization’s position in its October 2015 Protocols for Safe Havens for Works of Cultural Significance from Countries in Crisis. Under this framework, foreign owners of at-risk items can request the artifacts’ temporary safekeeping at various international museums.

The new document supersedes an earlier protocol, passed June 2008, and changes the organization’s position on ownership. While the older document affirms permanent acquisition by museums, the newer one uses the language of temporary safekeeping by promising the return of artifacts to their countries of origin. “The timing of the return of works will depend on the circumstances existing in the country from which the works were removed, but if possible should be effected as soon as practical after the situation giving rise to the need for a safe haven has passed,” the protocol states.

Anita Difanis, who handles government affairs for the group, said the association has shared the protocols widely throughout the international museum community in hopes of sparking conversation, especially at museums in the crisis area. Indeed, many legal experts think that little can be done by the United States, considering its distance from the epicenter of the crisis.

James McAndrew sits in his law office at GDLSK LLP on the 25th floor of a Park Avenue high rise. Diplomas and certificates line his walls while photographs of his children line his desk. Back in 1988, he was a special agent at U.S. Customs and Border Protection. McAndrew explained that at the time, there was only one agent in the entire country who had the responsibility of conducting investigations in the art and antiquities world– too few to do significant work in an area wrought with unregulation.

McAndrews understood how easily art could be used to launder money. “You can buy a $100 million Picasso painting, take it out of the frame, fold it in half, stick it inside your New York TImes newspaper, go through TSA, hand your newspaper to the TSA agent as you walk through the metal detector, and then come out the other side as the TSA guy gives back your newspaper,” McAndrew said. “Of course, $100 million of illicit proceeds.”

He developed the International Art Theft Program for Homeland Security. Over the course of 10 years, he trained some 400 agents in how to detect stolen works of art and arrange for their return to the rightful source countries.

“As I was being aggressive and training the agents to be aggressive in what to look for, I realized that there was no mechanisms or procedures in place for the collectors and dealers, auction houses, and museums to now respond to the mass amount of cultural claims,” McAndrew said. “So I felt like it got a little out of control with the government and I thought that it wasn’t what I was espousing as the person responsible for the training.”

The realization prompted McAndrews to enter private practice, where he is defending institutions that own disputed art. Having experienced both sides of the game, McAndrew is well versed in the powers and limitations of U.S. legal efforts. And in his opinion, none of them can combat the crisis of looting in the Middle East. These proposals are merely political soundbites, he said. While creating the impression that lawmakers are being proactive, they have little authority in these matters.

“We can pass all the resolutions in the world but there is nothing we can do,” he said. “The people that need to respond and lead are the countries in the region, the ones that surround Syria and Iraq.” In other words, since objects looted by ISIS are likely to pass through multiple countries before they ever—if ever—end up in the United States, it is critical for the countries that are closest to the conflict to take extra precautions to stop the illicit trade. McAndrews pointed to Lebanon and Cyprus as key places where a given work might “cool off.” “And then all of a sudden, three years later, it shows up in a shipment from Dubai or from Hong Kong into the U.S. and nothing on it says, ‘Oh by the way, I was just dug out of the ground in Iraq.’”

A solution, McAndrew said, could be the 1983 convention on the Cultural Property Implementation Act, which President Ronald Reagan signed into law. It clearly states that any source country which has undertaken internal measures to address the problem can request that the United States impose import restrictions on any of its archeological objects that have been looted and traded abroad. The idea is that both parties must put in equal effort; the responsibility cannot be solely that of the United States. “Now if Israel or Iran, for example, want to just close their eyes and say ‘I’m not doing anything,’ then we need to punish them [and] sanction those countries,” McAndrew said.

Technology might also offer a way forward. Palmyra once stood as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, housing some of the best-preserved temples in the region. Ever since ISIS took over the Syrian city and began the systematic destruction of its heritage sites, independent cultural organizations have been creating three-dimensional digital models of the destroyed monuments. The Arch of Triumph, a secular structure that was demolished by ISIS in October of 2015, has been digitally recreated in London’s Trafalgar Square. The replica weighs 11 tons and is 20 feet tall, which is two-thirds of the arch’s original size. Plans for installing such digital models at tourists sites in New York City are also in the works and news of the ISIS retreat from Palmyra in late March has given rise to thoughts of using the same technology to produce a replica of how the whole city once looked.

A replica of Palmyra’s Arch of Triumph has been temporarily recreated at Trafalgar Square in London. Image © Getty

While looters use the web as a marketplace for stolen antiquities, protectors of cultural heritage find it equally accommodating. International law enforcement agencies have set up online databases of looted items. The FBI’s database lists 15,000 objects and INTERPOL’s contains 48,000. This enables dealers and buyers to identify unauthorized items.

The Institute for Digital Archeology, a joint venture between Harvard University, Oxford University, and Dubai’s Museum of the Future, attempts to combine archeology with technology. Its Million Image Database Project has developed an inexpensive and easy-to-use three-dimensional camera with automated GPS stamping capacity. Volunteers take these cameras to UNESCO’s List of World Heritage in Danger and are tasked with taking pictures of the artifacts at those sites, in case they are looted in the future. These images are then sent back to the institute’s headquarters at Oxford

The photographs are stamped with a time and location that help track the movement of a given item. When one appears on the market, the images can be consulted to locate its excavation spot and approximate when it was looted. Some 1,000 cameras are in the field and to date, some 200,000 images have been scanned. By the end of the year, the institute hopes to have 5,000 cameras in circulation and a million images added to its database.

The barriers to effective response are manifold. To start with, the United States has broken diplomatic relations with Syria. The issue of looting in the Middle East is simply out of U.S. jurisdiction. The various proposals and resolutions that have been put forth by the United States or the United Nations do not carry the force of law. Although in August of 2015, the FBI posted an official statement advising prospective buyers to avoid purchasing undocumented artifacts from the Middle East, it was a warning and not a law. In February of 2015, the U.N. Security Council passed “Resolution 2199” as a call for the collective effort to stop the illegal trade of antiquities from conflict regions in the Middle East. But it stands as only a non-binding agreement among its signatories.

The sheer volatility of the region is a restriction in itself.

“Overcoming those dangers is huge in a place like Syria right now. It’s almost unfathomable how anything could come out, even the people can’t get out,”

said Anita Difanis of the AAMD. “So while [ISIS is] bombing cities and communities, it’s pretty hard to go in and do anything organized.”

In the early stages of the Syrian civil war, a group of 200 archeologists who called themselves the Monuments Men travelled unarmed through rebel territory with a shared mission to save ancient artifacts in Syria. The name is a reference to the historians, professors, and curators who protected artwork from Nazi looting during World War II, memorialized in a recent Hollywood film. But since the group’s formation four years ago, ISIS has killed 15 of the monuments men, one, 82-year-old Khaled al-Asaad, was the former general manager of Palmyra’s antiquities and museums. He was beheaded for refusing to reveal the locations of archeological objects.

Another hurdle is perhaps more conceptual and less obvious than the first: the issue of defining provenance in light of the current looting crisis. McAndrews explained its significance. “‘Provenance’ now becomes a real word,” he said. “Now I’ll say, define provenance. What’s acceptable provenance to you versus you, you, and you? And no one has a consistent answer. That’s a problem.”

In today’s art market, only 25 percent of the objects have undisputed provenance. As for the rest, nobody can say for certain where the pieces originate. McAndrew stated that this is also a result of shifting national borders over time. “Because the Ottoman Empire, when they defeated the Romans, are in this area. And the Babylonians go here,” McAndrew said, grabbing a piece of scrap paper from his folder and drawing out a rough sketch of the region. “And then they crossed and they didn’t have today’s modern-day boundaries. That’s a very key issue and it’s no one’s fault.”

A new report released by the National Center for Policy Analysis in January estimates that since 2013, ISIS has earned $36 million to $360 million from selling looted antiquities. To put into perspective just how much damage can be done with even this low estimate of $36 million, the report states that a terrorist attack on par with 9/11 only costs $400,000 to $500,000 to execute.

David Grantham, the author of the study and a senior fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis, argues that authorities need to realize the definite link between terrorism and illegal antiquities. He cites Al-Qaeda as another terrorist group that tried to use profits from the antiquities trade to fund its activities. In 1999, Mohamed Atta attempted to sell Afghan objects to a German university professor. He “claimed that he was selling artifacts to purchase an airplane.” Just two years later, Atta piloted a Boeing 767 into the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

“I think the military and the government can take a stronger action going into an area of conflict and we can probably do more there,” Grantham said, citing U.S. troops in Iraq as an example. “Assuming it’s coming from areas like Syria, where we don’t have troops on the ground per se, it becomes more cooperative.”

Antiquities organizations take a similar stance. In April, the Antiquities Coalition, the Middle East Institute, and the Asia Society created a task force report titled #CultureUnderThreat that demands military action by the White House.

“U.S. armed forces and their coalition partners should engage in military air strikes, as appropriated, against targets threatening known heritage sites as part of their comprehensive mission to defeat violent extremism,” the report said.

Grantham was a soldier himself in the mid-2000s. He was deployed to Afghanistan in 2006 and Iraq in 2008 on what he jokingly called an “all-expense-paid trip.” It was during his time as a Special Agent with the Air Force Office of Special Investigations that he had the opportunity to have prolonged interaction with Afghani and Iraqi locals and develop an appreciation for their cultures. It led him to study Arabic in Austin on his return to the United States.

On a fundamental level, how many people not involved in the issue understand the importance of cultural heritage and the need to protect it? For archaeologists, museum curators, and other experts in the field, providing an incentive for more people to care is first and foremost in finding a solution to the looting crisis. The task will not be an easy one judging by the attendance at the Wellesley conference in September. Only 20 people sat in an auditorium that can hold hundreds.

Disillusion and frustration permeated the space at the end of that day-long panel discussion. No conclusions were reached, no solutions were provided. The speakers could not seem to agree with one another and the audience members seemed unsure of whose opinions to take most seriously. Stephennie Mulder was one of the last to leave the auditorium. The UT-Austin professor stayed behind to chat with some of the students who attended the conference.

“By the way, not all academic conferences are like that,” she joked, referring to the heated debates that had occurred towards the end of the day. “Many are boring.”

As an archeologist and a scholar, Mulder believes her job is “to craft a narrative and raise a new generation of young people—and also of people who are already [my age] and older—to begin to shift consciousness on the significance of heritage in general.” She thinks that being well informed helps spark the incentive to care. The Temple of Bel in Palmyra, she said, is a perfect example. In August of 2015, ISIS blew up the structure, which has been standing since 32 A.D. Mulder explained that the parthenon-sized structure was considered to be of equivalent beauty and importance to its Greek counterpart.

The Temple of Bel before its destruction in August, 2015.

“But I wonder how many people have heard of the Temple of Bel before it was destroyed,” Mulder said. “If the Parthenon stands for the birth of democracy, the Temple of Bel stands for the kind of multi-cultural society that we all want to be a part of. And that idea was lost with the building, but how many people knew that?” ![]()