Migration Squared

Cubans who migrated to Venezuela escaping Fidel Castro, relived past experiences when Hugo Chavez rose to power. Two leftist regimes buffeted their destinies.

by Rachelle Krygier Azrak

By Rachelle Krygier Azrak

One afternoon last December, Madelin Martinez chatted as she blew dry my hair at a salon in Miami. Four months earlier, she had left her own beauty shop in Caracas in hands of her brother-in-law. Venezuela’s economic chaos and astounding levels of crime had driven her to seek a new life in the United States along with her husband and children. “One would wish to never have to migrate, mi niña,” she said. She turned off the blow dryer and looked into the mirror to meet my eyes. “It is exhausting. And scary.”

This was not the first time the 51-year-old woman with short blonde hair and tired blue eyes felt forced into such a decision. Thirty five years earlier, at age 17, Madelin and her family fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba for Caracas. In 2015, she found herself in the same position, looking to escape another government whose policies proved too delimiting. “It felt like I had really bad luck,” she said between ironic laughs.

The experience of Marvin Perez and his family was somewhat similar. In 1992, 28-year-old Marvin and his brother attempted to escape Cuba in a self-fashioned raft only to be apprehended about three miles off shore and brought back to the island. They were labeled dissenters; they and their family lost their jobs as a result. Marvin managed to get to Caracas and lived there for seven years, during which his family joined him. But their journey did not end in Venezuela. Less than two years after Hugo Chavez came to power, they crossed the Mexican border to seek parole in the United States.

Only the particulars make the stories of the Martinez and Perez families unique. They are among thousands of Cubans who fled to Venezuela after Castro came to power in 1959. Although Venezuela used to be the second largest site of Cuban diaspora after the United States, with some 40,000 Cubans calling the country home in the 1980s, the numbers dropped dramatically after Chavez came to power. A majority of those migrants have since sought refuge elsewhere, escaping the policies he put in place and that his hand-picked successor, President Nicolás Maduro Moros, has perpetuated since the death of Chavez in 2013. Today, only about 10,000 Cubans remain in in their adopted homeland.

Venezuela’s Cubans experienced first hand the whole of the Latin America’s transition to what scholars call the “new left,” a reference to the continent’s broad leftist political trend that began in the 1990s. It drew force from Castro’s political philosophy and, under the influence of Chavez, spread throughout the southern cone, reaching Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Nicaragua, and Uruguay.

My own family’s story differs somewhat in that our double migration—triple, actually—has taken place over three generations with relocations from Poland and Lithuania to Cuba to Venezuela to the United States. Yet it was these intercontinental movements that got me thinking about the ways in which the Castro and Chavez regimes have so directly shaped our lives and those of thousands of others.

My paternal great grandparents migrated from Eastern Europe to Cuba, escaping anti-Semitism and economic uncertainty. At the start of the 1960s, they all left Havana for Caracas with the first wave of émigrés who fled the Cuban Revolution. Since then, my aunt, my father’s youngest sibling, is the first and only Krygier to leave Venezuela permanently. She moved to Miami in 2007 for her children’s sake, to spare them Caracas’ growing atmosphere of delinquency, economic deterioration, and political fallout. I study in the United States, as does my cousin, the daughter of my father’s oldest sibling. Neither my cousin or I has decided whether to seek to stay after our student visas expire or to go back to Venezuela where our parents and grandparents still live.

Thinking about how much both the Cuban revolution and the upheaval caused by Chavez have buffeted my destiny and that of all my family members, I couldn’t help but wonder about the impact of this double migration on the thousands of Cuban migrants to Venezuela, who found themselves living under a system established by a leader who was advised and supported by the very regime they had fled Cuba to escape.

For Madelin Martinez, the hairstylist, the decision to uproot herself for the second time in 30 years has meant a long, tough journey to peace of mind. The effects of policies enacted by leftist regimes have been limiting and shaping her fate since Dec. 31, 1959, six years before she was born. On that night, the then president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista, escaped to the Dominican Republic, ending seven years of brutal dictatorship and prompting a triumph for Castro and his five-year-old 26th of July Movement.

Madelin Martinez at the salon she used to own in Caracas.

In the early hours of the following day, Castro, then 31, descended from the mountains where his movement had been waging guerrilla warfare, and headed to Santiago de Cuba. “The Revolution starts now,” he said, addressing an uproarious crowd of thousands. He declared the formation of a new government and marched across the island, entering Havana on Jan. 8. The parents of Martinez, now divorced, were adolescents at the time. Her mother, Norma Fanego, was 12 and her father, Rolando Martinez, was 14. They had not yet met, even though both lived in the same Havana neighborhood of El Cerro. They joined in the celebration with their neighbors, holding up signs and shouting slogans as they tussled with the crowds to get close enough to Castro to touch him as he paraded by.

Seated on the living room sofa of the house Martinez left behind in Caracas, her father, now 74, recalled how rapidly Communist and totalitarian policies took hold in Cuba. By the beginning of 1960, the Revolution had sentenced and killed about 490 opponents of the new regime. Near the end of the year, the United States declared its embargo and in the middle of 1961, conducted the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

That was also the year Castro publicly declared himself a Marxist Leninist. He closed newspapers and expropriated all privately owned companies, including oil refineries, factories, and casinos. “Not just that! Everything,” Rolando Martinez said. “The man who had a little stand of mangoes, the kiosk in the corner. Every little commerce.” He tended to be repetitious and went off on tangents as he went as with his story, like the one about why he divorced Martinez’s mother and married, Isabel, another Cuban woman whom he then divorced once in Venezuela “because she smoked cigarettes.” He married a third woman, a Venezuelan this time, because “Venezuelan women are beautiful.”

Rolando Martinez, at the house his daughter Madelin left behind in Caracas.

It was in recounting the events that drove his family from Cuba that he displayed the most emotion. His tone was passionate but laced with cynicism. His voice got louder at those points and his small blue eyes opened wide.

When the government expropriated the company that employed Rolando’s father, the older man continued working as a distributor, but for a new owner: the revolutionary government. Under the supervision of a commander of the regime, Rolando Martinez’s father drove his truck to shops around the neighborhood and stocked them with the popular La Estrella candies, chocolates, and cookies. Soon his wage dropped.

“Suddenly there were no ingredients to make the products with,” Rolando said. There was no chocolate to make the Spanish turron with . . . the specialty of La Estrella.” He clearly shared the local fondness for turrones before they—like so many other high quality products—disappeared from the Cuban market. He said that before the raw ingredients started to become unavailable, the La Estrella factory even employed an expert Spanish turronero to guide production of the nougat-style treat.

Rolando met his future wife at a social gathering near his home in 1962. They soon started dating. He was 17 years old and working as a draftsman at a government-owned company that built steel structures. With thin chalk, he drew the construction layouts of the bridges, roads and buildings that designers described to him. It was a job he loved, despite the poor pay. Norma Fanego was 15 years old and starting her senior year of high school. To help out with her family’s finances, every morning before she went to school, she worked in a factory, wrapping candy.

Rolando Martinez was happy enough in his work, but there was trouble in the home. His 19-year-old brother Reinaldo Martinez, was involved in anti-government activities that his family feared would lead to his arrest. Although Reinaldo had fought with Castro’s movement against Batista, he came to believe that the country’s new leader was betraying the Revolution and joined the Jóvenes Desafectos, a group of young men who became disaffected with Castro. “They realized that they had overthrown the Devil to replace him with Lucifer,” Rolando said between laughs. In 1963, a government secret service official infiltrated a meeting at which the group discussed plans to steal arms to incite revolt. Reinaldo was sentenced to nine years of prison.

One year later Rolando Martinez and Norma Fanego wed. He was 20 and Norma, 18. Unable to find housing of their own, they moved in with Rolando’s parents.

Near Miami International Airport, I met Fanego in her first floor apartment. She is 70 now, a matron in comfy sweatpants with burgundy-tinted hair. Seated in a big leather chair she asked countless nervous questions about my intentions before she spoke excitedly and at length. She said the home of her parents-in-law, with their son in prison, “was a house of mourning.”

By then Norma was working in a Havana beauty shop that the government had expropriated. In 1964, when she became pregnant with Madelin, clients brought her what were precious gifts in a time of such scarcity: diapers and milk.

As the regime took control of all the production on the island and started subsidizing products, the supply of everything, even the most basic goods—in fact, especially the basic goods—became precarious. To regulate food distribution, the government imposed the tarjetas de racionamiento system. Every household received ration cards that stipulated the amount of food that they could buy at government-regulated prices, depending on the number of family members. Although the lack of food was the most severe, cars, home appliances, medicines—almost all products became hard to come by.

To stay out of trouble the newlyweds would work at a Revolutionary Committee office near their house every other Sunday. They patrolled the neighborhood to see if anyone was involved in counter-revolutionary activities. They always returned with a blank report. They hated the job. They also bartered for products they lacked. Norma once worked at the salon for weeks without pay “because I needed a frigidaire,” she said, “and they gave it to me.”

Every week, Rolando would help his mother carry pots of lima beans to the tiny Isla de Pinos, now known as Isla de la Juventud, where his brother was serving out his sentence at the Presidio Modelo, but he was not allowed inside. Only their mother was. On one of their trips, Reinaldo gave their mother a gift for Rolando, a belt that he made with nylon. When Rolando put the belt around his waist, its two ends barely reached the bones on the sides of his hips. Rolando burst into tears. “‘How does this fit my brother,’ I said, ‘if he was so muscular. How is my brother doing then,” he asked his mother, “ How does he look?’”

By the time of Reinaldo’s release at age 29, Madelin Martinez was seven years old and had a three-year-old brother, Reinaldito, named in her uncle’s honor. The divorce of their parents came two years later and the children remained with their father. Norma Fanego moved back in with her own parents.

At home, Madelin often heard anti-government comments, especially from her uncle. Her father warned her never to repeat at school what she heard at home. “I lived terrified that something would come out of my mouth,” she said. One day a teacher asked her if her family was planning to leave the country, and she said yes, because she had heard that her uncle was making arrangements. If the government got wind of a family’s plans to leave, lost jobs were common with no new opportunities for work. It was seen as an act of treason. And there was shunning. Neighbors would gather in the streets to throw eggs and shout, gusanos, traidores. Worms. Traitors. Luckily, Madelin’s teacher did not pursue the question further.

Madelin remembers her childhood in Havana as “rather boring and simple,” but happy. “Cubans have great personalities,” she said. “They are joyful people, they are always joking and partying. But if you made a party, there was not much to eat or drink, so just sharing time with people was pretty much what we did. There were no soft drinks, no chocolate, no candy.” She played at the houses of friends, drew with chalk on the sidewalks, or played soccer in the streets. In the summers, the government mandated that children spend 45 days of the school vacation period at camp. They would wake up at 5 a.m and by 6 they would be on trucks standing for hours, until they got to the fields where they would spend the whole day picking potatoes and tomatoes. They ate mostly rice with beans, or whatever their parents managed to bring them on Sundays, when they were allowed to take the long trip to visit them.

Sometimes, during the school year, there were forays for ice cream at Copelia, when it was available, or to the movies, where technical glitches would often bring the screening to an end mid-show.

Rolando Martinez recalled a night at the movies in the late 1970s when a Castro newsreel was shown. His address included reference to Cuba being “on the right path,” in a “sea of happiness.” Rolando found Castro’s words so moving, they gave him goosebumps, even though he knew that what the president was saying was not true. “It was incredible,” Rolando said. “I turned to my friend and told him to look at my skin. And he said, ‘That is the power of good speech.’”

“Charisma,” Rolando said with a nod. “It is what all dictator’s rely on for power. From Hitler to Chavez.”

By 1980, Rolando’s brother managed to gain passage to Venezuela, which had begun to accept hundreds of ex-Cuban political prisoners. As Professor Holly Ackerman explains in an essay, this arrangement between the two countries was mutually beneficial. Castro was glad to get dissenters out of the country instead of keeping them in the prisons or unemployed in the streets, and the Venezuelan government welcomed the optics of accepting opponents of communism. The Cuban expat community in Venezuela was more than glad to absorb them. Once in Caracas, Reinaldo Martinez hoped his ex-prisoner status would help him obtain visas for the rest of his family, including Norma, as the mother of his nephews.

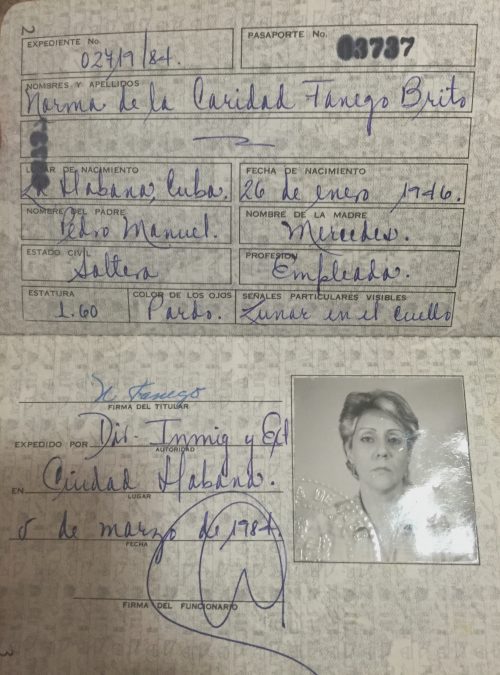

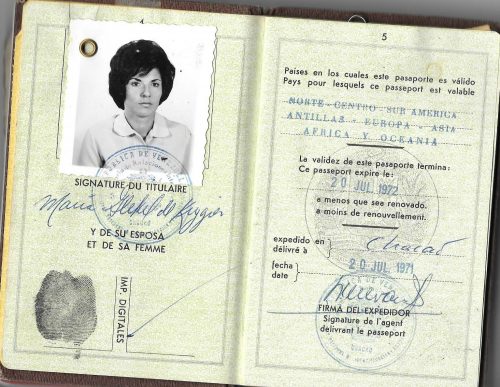

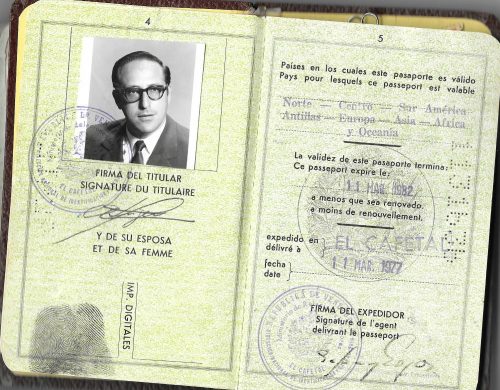

Norma Fanego’s Cuban passport

And it did. Four years later, he filed family reunification papers on their behalf and sent them money to pay for exit permission fees. Madelin Martinez packed all her belongings in a 12-pound suitcase—less “than you would put in for a one-week trip”—and boarded a plane with her mother, her brother, her father and his second wife, and her widowed grandmother. Before they left, government officials scoured the house to make sure they did not take more belongings than the law permitted. “They counted the knives, the forks, the television,” she said. “They didn’t even let you take your photos, your watch, nothing.”

The decision to relocate was especially difficult on Madelin’s mother. It meant leaving her own family in Cuba. True, she was with her children, but also with the family of the man she had been divorced from for a decade and his second wife. “I would have liked to have left by my own means,” she said, letting the thought trail off with raised eyebrows and a puckered forehead.

At dawn on May 9, 1984, the Martinez family arrived in Caracas. Madelin, by then 17, looked in amazement at the highway billboards advertising Coca Cola, Herbert Compote, and Mavesa Butter. “In Cuba all the signs said “Fidel” or “Martí” or “El Che Guevara,” she said. He first trip to a supermarket made her “dizzy,” she said. “with the amount of food and cans one besides the other.”

By the time the Martinez family arrived, Venezuela was receiving its third of five waves of Cuban émigrés. The community had grown to 13,000 with about 7,000 immigrants arriving during the period between 1978 and 1989. They were mostly former political prisoners and their largely lower middle class relatives. Among them were also some 900 travelers of the Mariel mass migration, which a sharp economic downturn in Cuba propelled in 1980. At that time, thousands of Cubans asked the Peruvian embassy for asylum and Castro allowed anyone who wanted to leave Cuba to do so.

In Caracas, the family moved into the two-bedroom apartment of Reinaldo and his wife in the center of Caracas. Rolando and his new wife promptly found work as janitors in a residential building, and Rolando soon was able to resume his career as a draftsman. Madelin and her mother took jobs as hairdressers at Sandro, a popular salon in the middle-class neighborhood of Chacaito. Through a co-worker, Madelin met her future husband, Javier Belloso, a Venezuelan who owned a computer accessories store.

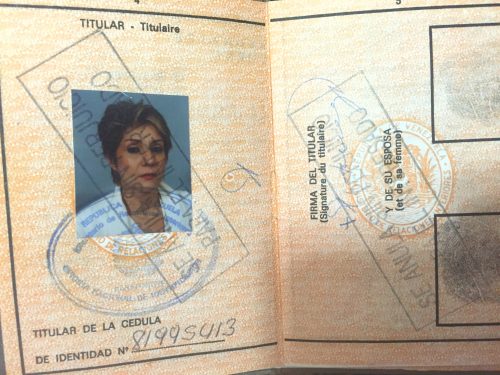

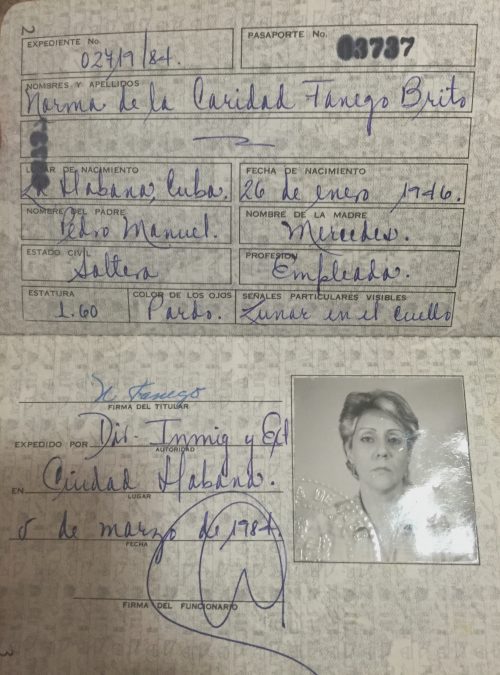

Norma Fanego’s Venezuelan passport

Life rolled along until 12 years later. Norma Fanego remembered the date, Feb. 4, 1992. She saw Chavez on television for the first time.. This was just before he went to jail for a failed coup against President Carlos Andres Perez. Chavez, wearing a red Castro-like beret, said “Comrades, for now we didn’t meet our objectives…I asume in front of you the responsibility of this Bolivarian military movement.” A year later, Perez’s successor, President Rafael Caldera, released Chavez in a move to differentiate himself from the corruption scandals and unpopular neoliberal reforms of his predecessor. Already there were rumors that Chavez would soon succeed in presidency. Indeed, Chavez visited Cuba in 1994 to start planning his 1998 presidential campaign with Castro’s help.

Norma began to obsess about a Cuban déjà vu and two years later, decided to leave Caracas in 1994, a good four years before Chavez became president. She packed up herself and her son, who was in the thrall of young local drug addicts, and moved to Miami on tourist visas. Once there, without working papers, she began working black, cleaning the floors of salons. Both she and her son were granted residency the following year as part of the Cuban Adjustment Act. Soon after, she passed a hairdresser course and was licensed to resume her profession doing cuts, blowouts and hair color once again.

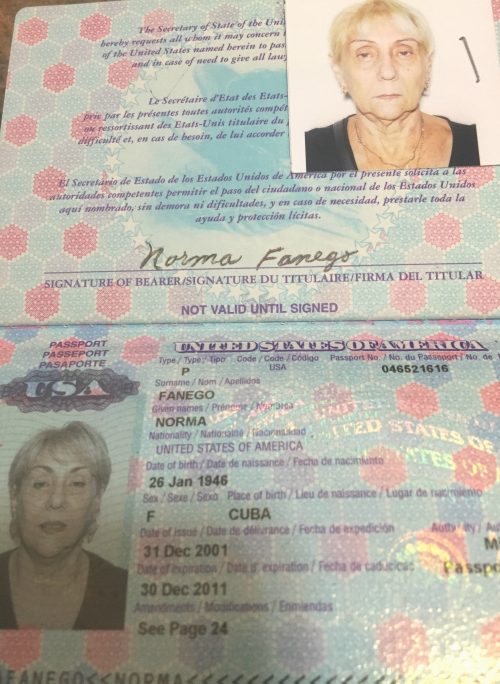

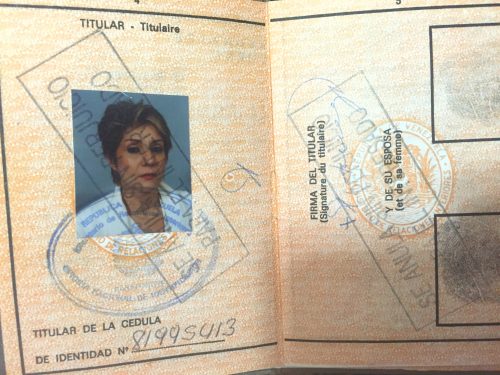

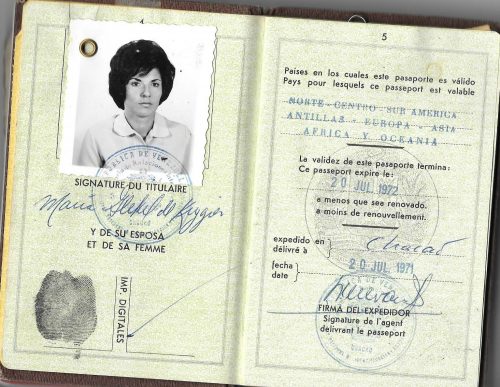

Norma Fanego’s American passport

Nonetheless, she was consumed with anxiety and bouts of depression. She had several minor car accidents and over the next five years, found it so difficult to concentrate at work that she went disability. “I was in a crisis,” she said. “All I did was cry. I didn’t know where to go. I wanted to go back to Venezuela, I wanted to go back to Cuba.” She mentioned her son and that he died in 2014, when he was in his late 30s. The details were still too difficult for her to discuss. “I have pain inside me. I have struggled with the changes of one country to another,” was all that she would say.

A study of migration psychology prepared by American Psychology Association found that when immigrants experience mental health difficulties, it is usually related to the immigration experience. It has been called “acculturative stress,” a condition that may cause depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. The study also found that the age of a person when the migration takes place “shapes how the migrant unfolds in the new society.” Assimilation for those closer to retirement age is always harder.

Norma walked me to the door of her apartment. “Mijita,” my little girl, she said when I turned around to leave, “don’t forget to talk in there about what happens to you when you migrate. Explain it, tu sabes?” You know? “When you migrate to any country in the world, even if you are able to do well financially, you stop being you. You understand? Sometimes I ask myself, what am I?” she said. “Cuban? Venezuelan? American? I am none of those.”

“Sometimes I ask myself, what am I?” she said. “Cuban? Venezuelan? American? I am none of those.”

Madelin Martinez did not make the decision to migrate to the United States until 21 years after her mother’s flight, and long after 1999, when she and her father first confirmed their suspicions about Chavez’s intentions. Together, they were watching a broadcast of one of his first speeches as president, one in which he said that Venezuela was swimming towards the “sea of happiness.” They gave each other a look. “‘You see,” her father remarked at the time, recalling this exact phrase from another dictator’s mouth. “This guy is going to do the same thing as the huevon [ jerk] of Fidel.”

The decision to leave was made harder by how well established her family had become in Caracas, where since 2007, Madelin had owned her own salon. But there were unmistakable links between the Castro regime they had escaped and the Venezuelan government under which they lived; Chavez visited Cuba 27 times throughout his rule, and spent the last days of his life there, getting treated for cancer.

By 2015, the underside of his Bolivarian Revolution was inescapable. When Madelin and I met at her Caracas salon, four months before our second encounter in Miami, her clients were complaining about how long they had to spend in supermarket lines to buy toilet paper and trying to figure out where the rumor mill said one could buy cooking oil. They brought their own hair products imported from abroad because they were none to be found in Caracas. The price of a mani-pedi was a third of the minimum wage. “It is, I would say, like Cuba in colors,” Madelin said in between the noise of the blow dryers, “Not as bad as was Cuba, but very similar.”

The Martinez migrated from Cuba to Venezuela in 1984. The mother, Norma Fanego, left Caracas to Miami in 1994. Madelin joined her in 2015. Rolando, the father, is still in Caracas.

On the morning of August 29, 2015, Madelin, her husband Javier, and their youngest child, Christian, left Caracas and landed at Miami international Airport in the evening. She showed the immigration officer her renewed Cuban passport and said that she wanted to adhere to the Cuban Adjustment Act.

The family was led to the Homeland Security room. They sat for hours. Madelin was anxious. After five hours of thorough questioning, document scanning, and fingerprint recordings, the officer granted them parole and explained the steps to follow from that point on. It was almost midnight. Their daughter, Melanie, a student at Miami Dade College had already gone through the parole process and was waiting for them outside the airport. She and Madelin broke into tears when they hugged. They had not seen each other since Christmas.

From the taxi, Madelin called her own mother, Norma. “She was crying so much my poor mami.” Norma was thrilled to have them nearby at last. It put her more at ease. Nonetheless, she said, “the damage is done, the emptiness is there.”

“After achieving all that I did in Venezuela, how am I going to do it all again, being 52 years old?”

As for Madelin, leaving Venezuela also brought a new set of hurts “because I truly valued the country even more than my own and, well, it turns out that the same thing happens to me again.” She nodded and looked down. “After achieving all that I did in Venezuela, how am I going to do it all again, being 52 years old?”

Last December, Marvin Perez invited me to his home north of Miami, in Kendall, for a Sunday morning breakfast of arepas and cuban dark coffee, a tradition his family started when they arrived in from Caracas in February 2000.

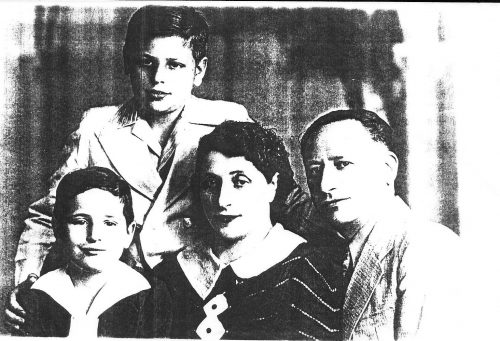

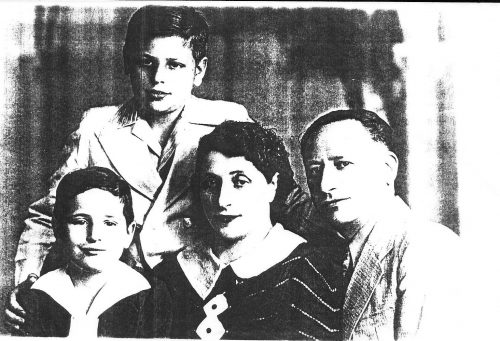

The Martinez having breakfast in their house in Kendall. From left to right: Claudia (Marvin’s daughter), Maira (Marvin’s wife), Marvin, Augusto (Marvin’s father), and Ana Maria (Marvin’s mother).

We all sliced our arepas open and filled them with egg and cheese. Ana Maria

Moros, Marvin’s 79-year-old mother, offered to prepare a plate for her husband, Marvin’s 77-year-old father, Augusto Perez. He declined in favor of coffee only. She had already eaten but helped herself to another arepa. Conversation quickly veered to the uselessness of renewing U.S. relations with Cuba and the absurdity of Venezuelan politics.

Marvin Perez

After the plates were cleared, Marvin told me about life in Cuba before his move to Caracas in 1993. Tears cut his voice. “I have beautiful memories of the people there,” he said, recalling his work as an electrical engineer at a government shipyard plant in Cienfuegos. He nodded toward his daughter, Claudia, who, at 18, aspires to be a journalist and was taking her own notes beside me. Marvin went on, “The people I worked with there, they were beautiful people. But they differed with me. In their political views.”

Although it took his family many years to decide to leave Cuba, the move to abandon Venezuela came quickly–only one year after the Chavez victory in 1998. The Perezes’ double migration differs from that of the Martinez clan not only in departure timelines but also in that they belong to a different professional and social class. Like Marvin, his two brothers are engineers. His mother, now retired, was a chemistry teacher, and his father, a professor and researcher in physics.

Between 1981 and 1985, as the former Soviet Union was collapsing, Marvin Perez studied electrical engineering at what is now the Eastern Ukranian University in the city of Lugansk, which was then Voroshilovgrad. This was under an arrangement that obliged him to go back to Cuba and work for the regime.

Marvin’s time in the Soviet Union coincided with talks of modernizing the country’s crumbling economy and eventually with the neoliberal reforms instituted under Perestroika during the presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev. Until his Soviet sojourn, Perez had never questioned his country’s communist system. But he now found himself nursing the hope that Cuba, too, would ride a similar “wave of change.”

“Instead of mounting the wave, the government distanced itself from it more and more”

What he found on return was the opposite. “Instead of mounting the wave, the government distanced itself from it more and more,” he said. Indeed the close relationship between Cuba and the Soviet Union dwindled. Castro was openly critical of Gorbachev’s reform efforts and of his impulse towards political democracy. Castro was also aware that the USSR’s ailing economy would mean a slowdown in the assistance on which Cuba relied. In a speech that Castro gave in 1989, when Gorbachev visited the island, he suggested that Cuba did not need the Perestroika measures because it was different “in size, ethnic diversity and history” from the USSR, and because it did not have to surmount the legacy of terror left by Stalin. “Unless you consider me a kind of Stalin,” he was quoted as saying jovially.

Augusto Perez

Marvin also found that his father’s work in physics at the Institute of Havana had been stymied. He wasn’t permitted to attend conferences or communicate with scientists in other parts of the world.¨I was isolated in essence because of an ideological issue,” Augusto said, raising his eyebrows. Only sporadically did Augusto let his guard down, like he did when I pointed to the two Cuban cigars that were peeking out of his shirt pocket. “I haven’t always liked smoking” he said, smiling and taking the cigars out to show me, “But about one year ago I started smoking one tabaco every Sunday.”

Augusto’s prospects at work fell even further when authorities caught Marvin and one of his brothers a mile off-coast of Cuba in a desperate and “rather immature” attempt to flee the country, as Marvin put it. It was 1992. Cuba was in a Periodo Especial, a time of severe economic crisis and high levels of repression. The chaos was exacerbated by an upsurge in the impact of the by then longstanding American embargo and the collapse of the Soviet Union a year earlier.

In times of such repression, to leave Cuba without permission was a punishable offense. Marvin and his brother were detained. The trials lasted one month. Since the government did not find evidence that they intended to “steal” any government property to take abroad (basically anything would be considered as such, but they threw themselves to the sea with nothing) they were freed. But by default, they lost their jobs: they were considered dissenters by all workplaces across the country. The blow immediately hit their family. Augusto was continually insulted by his bosses and peers, and gradually lost access to research tools. He finally quit, or as he put it, was “indirectly fired,” and started driving a cab.

Ana María Perez

Marvin’s mother Ana Maria, was working in the Education Ministry. Her chemistry books were used in schools throughout the country. But after the raft episode, she quit her job “because of ethical reasons,” she said. She did not want to work for the government any more. She started corresponding with a cousin in Venezuela to arrange for her children to migrate and the cousin soon filed family reunification papers. With the tips he received from tourists in dollars, Augusto covered the fees to get his children government permission to leave.. Months later, in December of 1993, Marvin and his brother boarded a plane to Caracas.

“Everything amazed me. The modern car I was picked up in, the modern buildings, the Christmas decorations.”

His first impressions were much like Madelin’s. Although he had lived outside of Cuba, he had never experienced capitalism in its full expression. “Everything amazed me,” he said, “The modern car I was picked up in, the modern buildings, the Christmas decorations.” Cuba’s secularity meant no national celebration of Christmas and although Ana Maria remained a Catholic, she kept it secret to protect the family.

Marvin, his brother, and their parents who joined them four years later, became part of a small fourth wave of Cuban migrants who arrived to Venezuela in the 1990s. Unlike the Martinez family who arrived in the ‘80s, when the country was experiencing relative growth and openness to immigration, the Perez family was greeted by a Venezuela cast into chaos by a slump in oil prices and a series of corruption scandals. As a result, Holly Ackerman explains in an essay, migration policies were strengthened and the inflow of Cubans slowed. Those who came, did so mostly through family reunification, like the Perezes, or through other unusual (and illegal) means. Experts say that it was then that Castro found in Hugo Chavez a figure that he envisioned would take advantage of the crisis and fill the void the fall of the USSR had left.

In January of 1993, Pepsicola Venezuela accepted Marvin’s application for a job in its factory, where he worked in the process of bottling. They sent him for training to Calabozo, a city about four hours away from Caracas.

It was in his first months in the Venezuelan plains that Marvin remembers first experiencing the fluctuations of a free economy. His first paycheck in the Venezuelan currency- Bolívar- was equivalent to 700 dollars and the second one, only one month later, was worth a hundred dollars less. “I was impressed. I had never seen devaluation or inflation,” he said. “There was no such thing in Cuba.”

Marvin struggled the first years to assimilate into a system where you worked and got paid fairly for what you did. “You have to learn to cope in such system,” he said. “Socialist systems are paternalistic. They give you everything, in very little quantities, but everything.”

Marvin delved into the rural culture of the Venezuelan plains. He listened to someone play the harp for the first time, danced to the rhythm of musica llanera and went to countless cock fights.

He was soon sent to Maracay, about two hours away from Caracas, where he had cousins and where, after a couple of months, he moved in with his future wife, Maira. In 1997 their first daughter Claudia was born, they got married, and Marvin’s parents emigrated from Cuba to join them. “I was desperate to reunite with my children,” Ana Maria told me with tears in her eyes.

Augusto said they assimilated quickly. “It was an extraordinarily similar feeling between the Cuban character and the Venezuelan one,¨ he said. “And the cultural life was similar to Cuba’s before Fidel.” Yet as a man in his late 50s, he was not able to find full-time employment. Ana Maria took massage courses. “I thought that if I didn’t work as a teacher, I needed to do something else,” she said. But only three months later, she found a position as a teacher at a high school. Chavez rose to power two years later.

“We Cubans,” Marvin said, “had already lived what you Venezuelans still had to live.”

“They say that if history doesn’t repeat itself, it rhymes,” Marvin said. The Perez were not going to wait. “We Cubans,” Marvin said, “had already lived what you Venezuelans still had to live.”

Marvin said to his friends, ojo pelao –beware- whenever they talked about politics. Augusto did so too. “But ideological processes always have an enthusiastic and utopia initial period, even for the most sensible and well-intentioned people,” he said. Ana Maria, too, tried to make her coworkers see that despite the fact that Chavez won by election and not by revolt, as Castro had, his ideas had the same glimmer.

Fausto Masó, a a well-known Caracas journalist and analyst, took a position similar to Ana Maria’s when we met last December at the Cafe Arabica, where businessmen and intellectuals meet for breakfast. Masó migrated from Cuba to Venezuela in the 1970s. He said Venezuela was nothing like Cuba because the government did not need such radicalism, and that Chavez was nothing like Fidel, because he did not need to be. For one thing, Venezuela had oil money that permitted Chavez to enact leftist policies without imposing a huge financial burden on the population and for another, global realities had changed since the Cold War era in which Castro came to power.

Masó’s response was reminiscent of something Castro himself had said back in 1999, three weeks after Chavez won the elections. “You cannot do what we did back in 1959,” he told an audience at the Central University of Venezuela. “You will have to be much more patient than us, and I’m referring to the part of the population that is craving immediate radical social and economic changes in the country. If the Cuban Revolution would have triumphed in a moment like this one, it would not have been able to sustain itself.”

“We never ever imagined when we migrated to Venezuela that there would be such a drastic political change,”

Still, what the Perez family heard, like did the Martinez, were the rumbles of impending loss of freedom. “We never ever imagined when we migrated to Venezuela that there would be such a drastic political change,” Ana Maria said. “What you value the most in those situations is liberty. And I felt it. And that’s why we left Venezuela right away.”

Marvin left before the rest of the family to figure out how they would all migrate. Near the end of 1999, without knowing that he was eligible for emigration to the United States under the Cuban Adjustment Act, or that he could go to the Mexican frontier and ask for parole at the U.S. booth, he crossed the Mexican border alone at Matamoros and walked over a bridge into Brownsville. The American authorities detained him for one month, until they sorted out that he was Cuban and sent him to Florida for court proceedings.

During his time detained in Brownsville he familiarized himself with the laws and told his parents and brothers to seek parole at the Mexican border, and his wife and daughter to enter as tourists and wait for him to obtain residency for them. By February 20, 2000, the whole family was in Miami.

Marvin Perez migrated from Havana to Caracas in 1993. His parents joined him in 1997. They all left Caracas to Miami in 2000.

After one year of court hearings during which Marvin worked installing rugs, the judges offered him residency. He accepted, and was able to extend the privilege to his wife and daughter. After jumping from installing rugs to wood floors to alarms, Marvin landed a job with Pepsicola in Orlando in 2002, again in their bottling factory. He worked there for six years until the 2008 housing crisis, when he decided it was a good time to buy a house in Miami where the rest of the family lived. By then, he and Maira had a second child, a son, whom they named after Marvin.

They moved to their current house in the south of Miami and Marvin started working at his current job at New Era, a company that produces electric energy. His wife Maira got a job in the cafeteria of the school where they sent their children. Their son is now 11 years old and Claudia, 19.

Marvin was 29 when he made his second transition. He is now 52. He said the move to Miami from Venezuela was not so hard because Miami is so much “an extension of Latin America. Here you can find croquetas cubanas and hallacas,” he said. They remain close to their Venezuelan connections—his wife’s family is there as are the godparents of their children and so many of their friends. Their last ties to Cuba are nearly gone. Almost no family remains there, save one maternal uncle, and so much time has passed since his departure.

When Augusto, the physicist, arrived in Miami, he started working in Publix, moving the shopping carts. After a few years he landed a position giving mathematics and physics lectures at Miami Dade College, where he still teaches. Ana Maria started as a teacher’s assistant and tutor for foreign students at South Miami Senior High but then began teaching chemistry at Miami Dade College. “I never wanted to leave, I was always scared. Not Cuba. Not Venezuela. If my children wouldn’t have left, I would have stayed. I always think that I will not be able to cope with the change. I then face it, I would say with some degree of success, but I’m always scared beforehand. The same happened when I arrived in Caracas,” she said. ‘Where do we start working? What do we do?’”

“Where do we start working? What do we do?”

The whole Perez family walked me to the door as I left. They stood outside the house and waved until I was out of view, in the way my paternal grandparents have always said goodbye when we leave their home. They walk us to the door of their apartment and keep waving until the elevator leaves. When I was in elementary school, I recall my parents complaining that it was dangerous for them to wait outside their previous house for a long time. Delinquency in Caracas was already a big issue.

On my way back to my friend’s home where I was staying, I called my parents to ask if perhaps this long goodbye might be a Cuban tradition. They laughed. My dad suggested that it might be an immigrant thing, “You know, of people who have experienced real farewells.” Maybe so, I thought, and remembered how hard it was for me to leave five years ago and how much I have always wanted to go back. This is not to compare my choice to pursue a career abroad to any of these migrants’ stories, but still, it was hard. Hard for my parents to let me go, hard to even think of the possibility of not going back. I tried not to cling to the thought, because the uncertainty is a constant source of frustration, and switched to recalling the summer afternoon I had spent with my grandfather in Caracas, piecing together the story of his parents’ escape from Poland to Cuba and then with him from Cuba to Venezuela. I thought of how hard it would be for him to migrate again.

My grandfather was sipping a marroncito, the coffee with milk he always favors, after our lunch of black beans, meat, rice and sweet plantains. He was sitting on the balcony of his apartment, eyes were fixated on the Avila mountain that surrounds the valley of Caracas. “And como se llama,”—how does one say—”we left Cuba and now tu sabes”—you know—“we are here… and ojala ojala”—hopefully—“Venezuela gets better,” he said, grabbing a cookie.

At 82, his sentences often include a como se llama and more than a few pauses while he tries to find words to express himself. As painful as these lapses are for the family, they must be even more so for a man as erudite as Alberto Krygier, who wrote about politics and economics for 20 years for El Nacional, and taught management at several universities in Caracas. This followed a 30-year career as an accountant and an economic consultant to former Venezuelan presidents Carlos Andres Perez and Jaime Lusinchi.

I put my guayoyito—Americano—on the glass table between us. His mind searched as we went on. “My mother, what was her name, I don’t remember her name. How can I? MARIA,” he shouted to my grandmother, who had gone back into the house to answer the telephone.

“Ana, Ana was her name right?,” I said.

“Eh?”

“Her name was Ana,” I said, louder this time.

“Si, Ana,” he said, rolling his eyes at his forgetfulness.

Ana Silberberg, my great grandmother, left the small Polish town of Stopnica in 1924. The three million Jews who lived in Poland then, were caught in between conflicts among the new neighbors of the Second Republic of Poland created by the Allied powers after World War I. Poles who associated Jews with the Bolshevik revolution massacred them throughout the country. My family’s economic condition declined as Jews were not allowed to work in civil service, public schools, or state-run monopolies.

Ana joined a group of Zionists who had planned to get to Palestine by way of Havana and the United States. She was a passionate Zionist and Communist, as were so many Jews in Eastern Europe at the time. In Havana, the wait for documents made the 25-year-old grow desperate. “She had no money so she smuggled in a boat” bound for Miami, my grandfather said and nodded, sliding his lower lip over his upper lip, a tick of his. When her boat arrived U.S. authorities detained her and deported her back to Cuba. “Cuba received her and also my dad,” Adada said. I brushed cookie crumbs off his shirt.

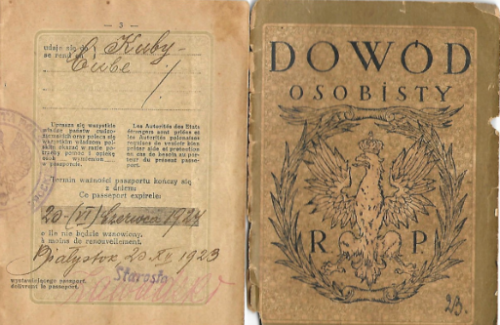

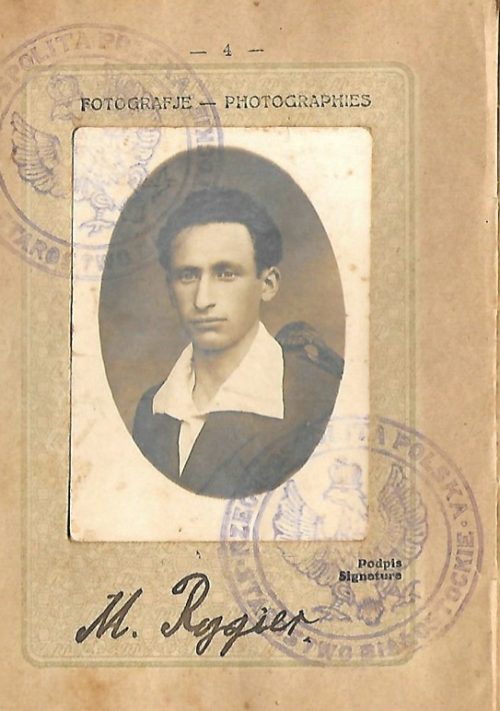

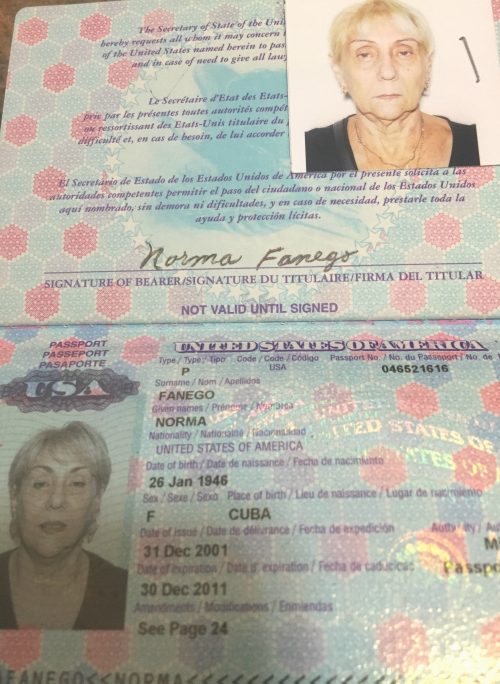

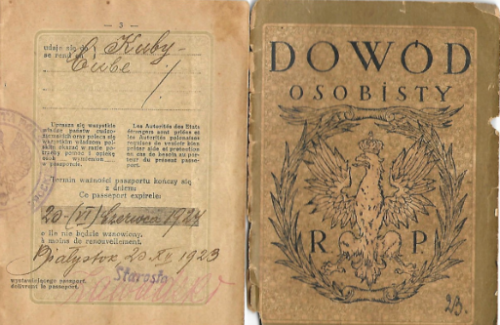

Max’s Polish Passport

Like Ana, my great grandfather Max Krygier, was a Zionist and a Communist who wanted to go to Palestine and work on a kibbutz. He fled his birth town of Staszow with a group that hoped to reach Palestine via Germany. But in Berlin, they were unable to get the required permits, so Max joined his brother to travel to Cuba in 1923 with the idea of getting to the United States from there.

My greatgrandfather Max’s Polish passport.

Ana and Max both became part of a wave of Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern European and Russia who arrived in Havana at that time. An established community of 8,000 Jews helped them find their way during their first years on the Caribbean Island. They soon met and married in 1929. They climbed the ladder to the upper middle class when Max came to own a shoe shop. Two years later, my grandfather’s older brother, Eduardo, was born. In 1934 my grandfather, Alberto, was born.

Most of the Cuban Jewish community arrived in the manner of my great grandparents–empty handed. In fact Cuba had been receiving Jews as far back as 1492 when the Inquisition expelled them from Spain. In the 1920s, Sephardic Jews arrived from Central Europe and Turkey as the Turkish war of liberation unfolded, and in the early 1940s, some 3,000 Jews found refuge on the island, escaping the Nazis.

By 1952, the Jewish population of Cuba had grown to 15,000. Mostly businessmen, Jews were involved in all aspects of Cuban economy, especially sugarcane, tobacco, and the garment business. My grandmother’s dad, Jacobo Glekel, for example, who had arrived to Cuba from Lithuania in the early 1920s, had a men’s clothing shop.

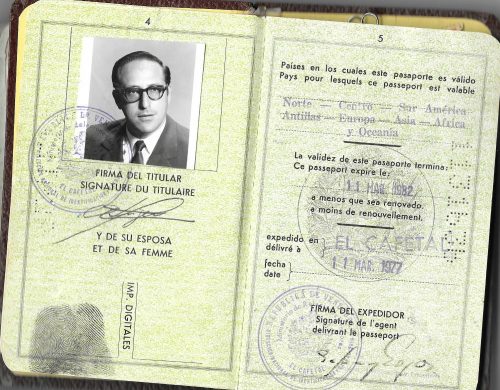

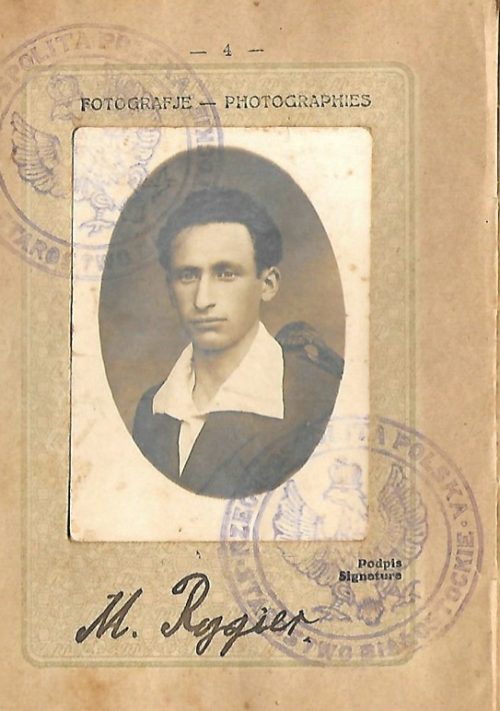

From left to right: Alberto, Eduardo, Ana, and Max

Adada—like we call my grandfather—and my grandmother Maria Glekel met in 1955 at the Casino Deportivo, a club in Havana where the Jewish youth came together in the afternoons. Adada was 21 years old and in college and Mima—as we in the family call my grandmother—was 16 and still in high school.

While studying at the University of Havana for a law degree by day and an accounting degree by night, Adada worked with student groups to overthrow Batista. In a way, he was engaged in efforts that advanced Castro’s cause.

The dictatorship notwithstanding, my grandparents remember their lives in Cuba as joyful, tranquil, and culturally engaged. Their childhood friend, Ida Schumer, whose parents were also Polish refugees, recalls Havana as the quintessence of modernity. “We were in the last Coca Cola of the desert,” she said.

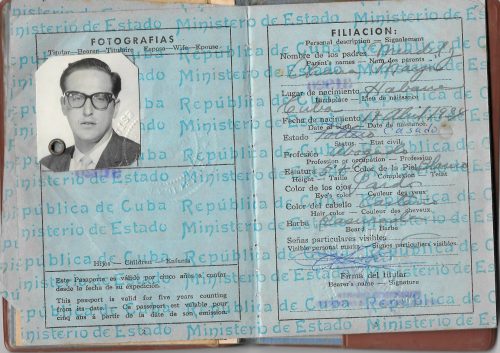

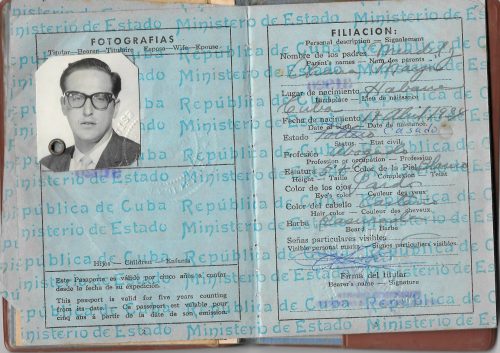

Alberto’s Cuban passport

In 1957, while Adada was studying in New Orleans for a masters degree in consulting from Tulane, it took weeks for the letters he sent back to my grandmother in Havana to arrive. Mima remembers his long detailed accounts of his whereabouts, his impeccable spelling and the poetic phrasing of his sentences. They married in Havana a year later, in 1958. Mima was 20 years old; Adada was 25. They promptly moved to New York where he went to work for the then “Big Five” accounting firm, Arthur Andersen. Their plan was to go back to Cuba after a year or two.

From their new home on West 8th Street, they celebrated Castro’s triumph. But in the end of 1959, when Mima gave Adada an ultimatum to leave New York because she couldn’t stand the cold winters, Castro’s fusillading of opponents and confiscation of lands and businesses made the prospect of return untenable. Friends back home were trying to leave and their parents were struggling to keep their businesses going.

In 1960, Adada accepted a transfer to Venezuela, a tropical South American country where some of his friends had already established. It was growing, foreign-owned companies were flourishing, the economy was stable, and the culture, the language and the people were similar to Cuba’s. Plus, it was summer all year round so Maria would not complain.

One year later, the Castro government confiscated the shoe shop of one of my great grandfathers and the men’s clothing store of the other. They and their wives filled one suitcase each and went to Caracas to live with my grandparents. By then, Venezuelan President Romulo Betancourt was leading what the Cuban government called “hemispheric aggressions” against the revolution.

Alberto’s Venezuelan passport

My grandfather’s story is like that of other Jewish Cubans whose families, over generations, in the space of 95 years, have migrated three times. Most of their families went to Cuba from the Middle East, Western and Eastern Europe, and then left during the first years of Castro’s rule, when the Jewish Community of Cuba was reduced by two times. Generally educated professionals, now between the ages of 80 and 90, they arrived to Venezuela about 40 years before Chavez came to power, joining a Jewish community that like Cuba’s was constituted by migrants from all around the world. Most of them either migrated or have children who did so throughout the Bolivarian Revolution. Ida Schumer, who arrived in Caracas in 1960, expressed it this way: “We the Jews have the button of just running away. Sadly, it is in our souls.”

“We the Jews have the button of just running away. Sadly, it is in our souls.”

Maria’s Venezuelan passport

My Aunt Francis was born in Caracas, two years after my grandparents arrived and my father, Aron, came two years later, in 1964. By the time my Aunt Tamara was born in 1971, my grandparents were well-established, as were the 15,000 members of the growing Jewish community. (By then the community in Cuba had been reduced to only 800 members). Adada had founded a successful consulting firm, Krygier & Asociados, following a decade with Arthur Andersen as one of its main representatives in Latin America. His two bouts working as a presidential adviser took place between 1974 and 1989.

A decade later, Chavez triumphed and within a year he changed the name of the country to Republica Bolivariana de Venezuela, created a new constitution, and made other adjustments that expanded the range of his powers. Within four years, he nationalized Venezuela’s rich oil resources and started expropriating private companies. By 2013, a total of 1285 private businesses had been shifted to government control. Like Castro’s, Chavez’s speeches vilified the middle and upper classes, accused their members of imperialism and responsibility for all the country’s problems, and extolled the hero of the country’s independence movement, Simon Bolivar.

My greatgrandparents Max and Ana migrated separately from Poland to Cuba in 1924. They both left Havana to Caracas in 1961, joining my grandfather Alberto and my grandmother Maria who arrived in 1960.

My grandparents did not leave. Their whole lives were in Venezuela: their work, their children, grandchildren and now great grandchildren. They have aged as their adopted country has come to resemble what they had hoped to leave behind.

I was only five years old in 1999, but I recall hearing my family’s conversations throughout my childhood; Mima’s warnings ya tu vas a ver—you will soon see—how this will turn into Cuba. And her children’s inevitable reply: Don’t exaggerate Ma. It’s not the same.

My mom remembers that Mima in fact predicted what would happen in very specific ways. She said for example, that something similar to the Milicias Cubanas would emerge, groups of people who would sign up to defend the revolution through medical, educational and military programs. My mother remembers how farfetched that idea seemed before it took root in Venezuela. And yet in 2003, the government established the Misiones and in 2005, the Bolivarian Militia. It then turned out that a substantial part of the workers would be sent directly from Cuba.

This past January, I met in Caracas with political scientist Carlos Romero, a professor at the Universidad Católica Andres Bello, at a cafe that had no water to serve us. He elaborated on the 40,000 Cuban workers who had come to Venezuela by 2007 as part of a treaty between the two countries: Venezuelan oil was traded for Cuban labor. They outnumbered the core Cuban community in Venezuela which currently has about 10 thousand members. He said the workers could be seen as the fifth wave of Cuban migrants to the country. Thousands of them—20,000, Romero specified-—have since “deserted” the program and sought residency in the United States.

Slogan on Caracas highway: “Only through Socialism we will have homeland.”

In 2014, the year after Chavez died, oil prices plummeted from $100 a barrel to $62, a loss of government revenue so drastic it exposed the previous 17 years of economic mismanagement. Nicolas Maduro followed Chavez as president, winning what many charged were fraudulent elections. Oil prices declined again to $37 a barrel, deepening the economic crisis even further.

Now illustrations of Chavez’s eyes linger on Caracas buildings and graffiti of his face on street side walls. His slogans are still on the billboards where commercial advertisements had dazzled Martinez when she first arrived. Yet never has the Chavista government been so unpopular. The fallout from the failures of the regime are pervasive. Even the the poor, the regime’s main support base, has lost faith.

Residents waiting in line to enter Government sponsored supermarket in Petare, an slum in Caracas.

Residents are only able to buy basic food items on a specific days of the week depending on the last digit of their national identification cards, their cedulas, an echo for the country’s Cuban natives of the tarjetas de racionamiento. Those with the means can resort to the black market where 11 cartons of milk recently cost my father the equivalent of a month’s minimum wage. Medicines, toilet paper, and harina pan, the flour to make arepas and empanadas, are either too expensive or impossible to find.

The unemployment rate is the highest in Latin America. The currency’s official value compared with the dollar is not even 10 percent of its value on the black market. The IMF predicts the inflation rate in Venezuela will reach 700 percent this year, the highest in the world on par with Zimbabwe’s in its hyperinflation days in 2006.

The severity of the crisis has led to an increase in the already intense sense of insecurity. Conditions were already difficult before Chavez came to power but became worse with every year of his rule. Venezuela now has the world’s second highest homicide rate, and Caracas holds the world’s No. 1 spot among cities. Kidnappings and assaults are everyday occurrences.

Conversations at our Shabbat tables and in our family Whatsapp groups (both maternal and paternal) have veered to urgent concerns. “Good morning. I need bleach, dishwashing soap, detergent, and skim milk. That’s it for now. Thank you,” typed my grandmother recently.

Who needs olive oil or shampoo? I have a contact who has both.

Since you are going to Miami soon, can you bring some Ensure for Adada?

Have you seen what apples are worth?

Food was awful last night. Restaurants are getting bad, right?

Sometimes there are jokes. My uncle likes to say, But we have Patria! But we have homeland, a Chavez saying to justify the struggles that his revolution caused.

My father is an oncological surgeon. Although the price of a visit to a doctor’s office costs the same as five packs of flour on the black market, migrating would pose even greater challenges. At 52, he would not only have to struggle with growing a practice, but would have years to spend to re-validate his medical credentials before he could see patients. But even more than this holds us back from leaving Venezuela permanently. Our strong sense of belonging persists.

But even more than this holds us back from leaving Venezuela permanently. Our strong sense of belonging persists.

In the 2012 presidential election where opposition leader Henrique Capriles Radonski campaigned against Hugo Chavez, I went home from New York for the weekend, just to vote. That night we all shouted at each other, mostly at my dad, who was not admitting the gravity of what had happened. The country will soon hit rock bottom and change will come, he said. My mother, who usually takes his side and is our most optimistic voice, even joined my brothers and me in a show of frustration.

We had the same reaction in 2013, when Capriles denounced as fraud the election win of Maduro’s by little more than 1 percent of the vote. Months later, my brother joined bands of furious students in the streets. I remember containing my tears in class as a photo of him appeared in my Whatsapp feed, getting in the front lines of a protest that was dispersed with tear gas. In various demonstrations, 43 people died and hundreds of others were detained. I swear I tried to stop him, my mother texted me, but he’s enraged.

Then last Dec. 6, a coalition of opposition parties won the legislative elections. I called my mother at midnight and we spoke for half an hour between bouts of laughter and tears. For the first time in 17 years, the prospect of the Venezuela my family had come to call home might not be lost. Might. The opposition is currently going through the process of recollecting signatures to revoke the president through a referendum. Our family’s future, like that of the country’s, is still as it has been as long I can remember: absolutely uncertain.

But we all try to remain hopeful as we have been taught since we were very young. When I was 12, my parents engaged passionately in all of the protests of 2002 that ended in a failed coup attempt against Chavez. The jean jacket that my mother had worn during the marches, full of Venezuelan flag pins and opposition symbols, hung in our living room for many years. She took it down at some point, when the memories it occasioned became too bitter for us all. Just the other day, I asked her what had become of it. “I keep it safe, as a historic document of how much we have fought to achieve our so much awaited democracy, our liberty!,” she texted back. “Every time I add a new pin, I hang it back in the closet with the certainty that, although it might not be the last one, the story will end with the jacket framed in an acrylic box and hanged in the most inescapable wall of the house. I do not lose hope” Days later, she clarified: “It’s not only that we don’t lose hope. There’s a lot of us Venezuelans who are convinced that countries don’t die, and that if we don’t end up participating in its reconstruction, we have raised children who will.”

Notes:

- Carlos A. Romero, Cuba y Venezuela: “La génesis y el desarrollo de una utopía bilateral”. Recollection of Essays: Cuba, Estados Unidos, y América Latina frente a los desafíos hemisféricos. Icaria Editorial- Ediciones CRIES 2011.

- Holly Ackerman, Different Diasporas: Cubans in Venezuela, 1959-1998. Collection of Essays: Cuba: Idea of a Nation Displaced. Edited by Adrea O’Reilly Herrera. State University of New York Press, 2007

- Josefina Rios Hernandez and Amanda Contreras, Los Cubanos: Sociología de una comunidad de inmigrantes en Venezuela. Fondo Editorial Tropykos. Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales-UCV Caracas, 1996.

- Unmarked: Crossroads. The psychology of immigration in the New Century. American Psychology Association 2002.

- Fidel en Caracas: ¨una revolución sólo puede ser hija de la cultura y las ideas¨ Oficina de publicaciones del Consejo de Estado, La Havana, 1999.

- Carlos A. Romero, Cuba y Venezuela: “La génesis y el desarrollo de una utopía bilateral”. Recollection of Essays: Cuba, Estados Unidos, y América Latina frente a los desafíos hemisféricos. Icaria Editorial- Ediciones CRIES 2011.

- Carlos A. Romero, Cuba y Venezuela: “La génesis y el desarrollo de una utopía bilateral”. Recollection of Essays: Cuba, Estados Unidos, y América Latina frente a los desafíos hemisféricos. Icaria Editorial- Ediciones CRIES 2011.

- Venezuela is now Cuba’s main commercial partner. In 2009 it was calculated that 25 percent of its exports and 31% of its imports are to and from the island. It exports oil and its derivatives, textiles and construction materials while it imports technical assistance, medicines and labor. Cuba owed by 2009 4,975 million dollars, 24% of which was owed to PDVSA. (Carlos A. Romero, Cuba y Venezuela: “La génesis y el desarrollo de una utopía bilateral”. Recollection of Essays: Cuba, Estados Unidos, y América Latina frente a los desafíos hemisféricos. Icaria Editorial- Ediciones CRIES 2011.)

By Rachelle Krygier Azrak

One afternoon last December, Madelin Martinez chatted as she blew dry my hair at a salon in Miami. Four months earlier, she had left her own beauty shop in Caracas in hands of her brother-in-law. Venezuela’s economic chaos and astounding levels of crime had driven her to seek a new life in the United States along with her husband and children. “One would wish to never have to migrate, mi niña,” she said. She turned off the blow dryer and looked into the mirror to meet my eyes. “It is exhausting. And scary.”

This was not the first time the 51-year-old woman with short blonde hair and tired blue eyes felt forced into such a decision. Thirty five years earlier, at age 17, Madelin and her family fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba for Caracas. In 2015, she found herself in the same position, looking to escape another government whose policies proved too delimiting. “It felt like I had really bad luck,” she said between ironic laughs.

The experience of Marvin Perez and his family was somewhat similar. In 1992, 28-year-old Marvin and his brother attempted to escape Cuba in a self-fashioned raft only to be apprehended about three miles off shore and brought back to the island. They were labeled dissenters; they and their family lost their jobs as a result. Marvin managed to get to Caracas and lived there for seven years, during which his family joined him. But their journey did not end in Venezuela. Less than two years after Hugo Chavez came to power, they crossed the Mexican border to seek parole in the United States.

Only the particulars make the stories of the Martinez and Perez families unique. They are among thousands of Cubans who fled to Venezuela after Castro came to power in 1959. Although Venezuela used to be the second largest site of Cuban diaspora after the United States, with some 40,000 Cubans calling the country home in the 1980s, the numbers dropped dramatically after Chavez came to power. A majority of those migrants have since sought refuge elsewhere, escaping the policies he put in place and that his hand-picked successor, President Nicolás Maduro Moros, has perpetuated since the death of Chavez in 2013. Today, only about 10,000 Cubans remain in in their adopted homeland.

Venezuela’s Cubans experienced first hand the whole of the Latin America’s transition to what scholars call the “new left,” a reference to the continent’s broad leftist political trend that began in the 1990s. It drew force from Castro’s political philosophy and, under the influence of Chavez, spread throughout the southern cone, reaching Bolivia, Ecuador, Brazil, Argentina, Nicaragua, and Uruguay.

My own family’s story differs somewhat in that our double migration—triple, actually—has taken place over three generations with relocations from Poland and Lithuania to Cuba to Venezuela to the United States. Yet it was these intercontinental movements that got me thinking about the ways in which the Castro and Chavez regimes have so directly shaped our lives and those of thousands of others.

My paternal great grandparents migrated from Eastern Europe to Cuba, escaping anti-Semitism and economic uncertainty. At the start of the 1960s, they all left Havana for Caracas with the first wave of émigrés who fled the Cuban Revolution. Since then, my aunt, my father’s youngest sibling, is the first and only Krygier to leave Venezuela permanently. She moved to Miami in 2007 for her children’s sake, to spare them Caracas’ growing atmosphere of delinquency, economic deterioration, and political fallout. I study in the United States, as does my cousin, the daughter of my father’s oldest sibling. Neither my cousin or I has decided whether to seek to stay after our student visas expire or to go back to Venezuela where our parents and grandparents still live.

Thinking about how much both the Cuban revolution and the upheaval caused by Chavez have buffeted my destiny and that of all my family members, I couldn’t help but wonder about the impact of this double migration on the thousands of Cuban migrants to Venezuela, who found themselves living under a system established by a leader who was advised and supported by the very regime they had fled Cuba to escape.

![]()

For Madelin Martinez, the hairstylist, the decision to uproot herself for the second time in 30 years has meant a long, tough journey to peace of mind. The effects of policies enacted by leftist regimes have been limiting and shaping her fate since Dec. 31, 1959, six years before she was born. On that night, the then president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista, escaped to the Dominican Republic, ending seven years of brutal dictatorship and prompting a triumph for Castro and his five-year-old 26th of July Movement.

Madelin Martinez at the salon she used to own in Caracas.

In the early hours of the following day, Castro, then 31, descended from the mountains where his movement had been waging guerrilla warfare, and headed to Santiago de Cuba. “The Revolution starts now,” he said, addressing an uproarious crowd of thousands. He declared the formation of a new government and marched across the island, entering Havana on Jan. 8. The parents of Martinez, now divorced, were adolescents at the time. Her mother, Norma Fanego, was 12 and her father, Rolando Martinez, was 14. They had not yet met, even though both lived in the same Havana neighborhood of El Cerro. They joined in the celebration with their neighbors, holding up signs and shouting slogans as they tussled with the crowds to get close enough to Castro to touch him as he paraded by.

Seated on the living room sofa of the house Martinez left behind in Caracas, her father, now 74, recalled how rapidly Communist and totalitarian policies took hold in Cuba. By the beginning of 1960, the Revolution had sentenced and killed about 490 opponents of the new regime. Near the end of the year, the United States declared its embargo and in the middle of 1961, conducted the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

That was also the year Castro publicly declared himself a Marxist Leninist. He closed newspapers and expropriated all privately owned companies, including oil refineries, factories, and casinos. “Not just that! Everything,” Rolando Martinez said. “The man who had a little stand of mangoes, the kiosk in the corner. Every little commerce.” He tended to be repetitious and went off on tangents as he went as with his story, like the one about why he divorced Martinez’s mother and married, Isabel, another Cuban woman whom he then divorced once in Venezuela “because she smoked cigarettes.” He married a third woman, a Venezuelan this time, because “Venezuelan women are beautiful.”

Rolando Martinez, at the house his daughter Madelin left behind in Caracas.

It was in recounting the events that drove his family from Cuba that he displayed the most emotion. His tone was passionate but laced with cynicism. His voice got louder at those points and his small blue eyes opened wide.

When the government expropriated the company that employed Rolando’s father, the older man continued working as a distributor, but for a new owner: the revolutionary government. Under the supervision of a commander of the regime, Rolando Martinez’s father drove his truck to shops around the neighborhood and stocked them with the popular La Estrella candies, chocolates, and cookies. Soon his wage dropped.

“Suddenly there were no ingredients to make the products with,” Rolando said. There was no chocolate to make the Spanish turron with . . . the specialty of La Estrella.” He clearly shared the local fondness for turrones before they—like so many other high quality products—disappeared from the Cuban market. He said that before the raw ingredients started to become unavailable, the La Estrella factory even employed an expert Spanish turronero to guide production of the nougat-style treat.

Rolando met his future wife at a social gathering near his home in 1962. They soon started dating. He was 17 years old and working as a draftsman at a government-owned company that built steel structures. With thin chalk, he drew the construction layouts of the bridges, roads and buildings that designers described to him. It was a job he loved, despite the poor pay. Norma Fanego was 15 years old and starting her senior year of high school. To help out with her family’s finances, every morning before she went to school, she worked in a factory, wrapping candy.

Rolando Martinez was happy enough in his work, but there was trouble in the home. His 19-year-old brother Reinaldo Martinez, was involved in anti-government activities that his family feared would lead to his arrest. Although Reinaldo had fought with Castro’s movement against Batista, he came to believe that the country’s new leader was betraying the Revolution and joined the Jóvenes Desafectos, a group of young men who became disaffected with Castro. “They realized that they had overthrown the Devil to replace him with Lucifer,” Rolando said between laughs. In 1963, a government secret service official infiltrated a meeting at which the group discussed plans to steal arms to incite revolt. Reinaldo was sentenced to nine years of prison.

One year later Rolando Martinez and Norma Fanego wed. He was 20 and Norma, 18. Unable to find housing of their own, they moved in with Rolando’s parents.

Near Miami International Airport, I met Fanego in her first floor apartment. She is 70 now, a matron in comfy sweatpants with burgundy-tinted hair. Seated in a big leather chair she asked countless nervous questions about my intentions before she spoke excitedly and at length. She said the home of her parents-in-law, with their son in prison, “was a house of mourning.”

By then Norma was working in a Havana beauty shop that the government had expropriated. In 1964, when she became pregnant with Madelin, clients brought her what were precious gifts in a time of such scarcity: diapers and milk.

As the regime took control of all the production on the island and started subsidizing products, the supply of everything, even the most basic goods—in fact, especially the basic goods—became precarious. To regulate food distribution, the government imposed the tarjetas de racionamiento system. Every household received ration cards that stipulated the amount of food that they could buy at government-regulated prices, depending on the number of family members. Although the lack of food was the most severe, cars, home appliances, medicines—almost all products became hard to come by.

To stay out of trouble the newlyweds would work at a Revolutionary Committee office near their house every other Sunday. They patrolled the neighborhood to see if anyone was involved in counter-revolutionary activities. They always returned with a blank report. They hated the job. They also bartered for products they lacked. Norma once worked at the salon for weeks without pay “because I needed a frigidaire,” she said, “and they gave it to me.”

Every week, Rolando would help his mother carry pots of lima beans to the tiny Isla de Pinos, now known as Isla de la Juventud, where his brother was serving out his sentence at the Presidio Modelo, but he was not allowed inside. Only their mother was. On one of their trips, Reinaldo gave their mother a gift for Rolando, a belt that he made with nylon. When Rolando put the belt around his waist, its two ends barely reached the bones on the sides of his hips. Rolando burst into tears. “‘How does this fit my brother,’ I said, ‘if he was so muscular. How is my brother doing then,” he asked his mother, “ How does he look?’”

By the time of Reinaldo’s release at age 29, Madelin Martinez was seven years old and had a three-year-old brother, Reinaldito, named in her uncle’s honor. The divorce of their parents came two years later and the children remained with their father. Norma Fanego moved back in with her own parents.

At home, Madelin often heard anti-government comments, especially from her uncle. Her father warned her never to repeat at school what she heard at home. “I lived terrified that something would come out of my mouth,” she said. One day a teacher asked her if her family was planning to leave the country, and she said yes, because she had heard that her uncle was making arrangements. If the government got wind of a family’s plans to leave, lost jobs were common with no new opportunities for work. It was seen as an act of treason. And there was shunning. Neighbors would gather in the streets to throw eggs and shout, gusanos, traidores. Worms. Traitors. Luckily, Madelin’s teacher did not pursue the question further.

Madelin remembers her childhood in Havana as “rather boring and simple,” but happy. “Cubans have great personalities,” she said. “They are joyful people, they are always joking and partying. But if you made a party, there was not much to eat or drink, so just sharing time with people was pretty much what we did. There were no soft drinks, no chocolate, no candy.” She played at the houses of friends, drew with chalk on the sidewalks, or played soccer in the streets. In the summers, the government mandated that children spend 45 days of the school vacation period at camp. They would wake up at 5 a.m and by 6 they would be on trucks standing for hours, until they got to the fields where they would spend the whole day picking potatoes and tomatoes. They ate mostly rice with beans, or whatever their parents managed to bring them on Sundays, when they were allowed to take the long trip to visit them.

Sometimes, during the school year, there were forays for ice cream at Copelia, when it was available, or to the movies, where technical glitches would often bring the screening to an end mid-show.

Rolando Martinez recalled a night at the movies in the late 1970s when a Castro newsreel was shown. His address included reference to Cuba being “on the right path,” in a “sea of happiness.” Rolando found Castro’s words so moving, they gave him goosebumps, even though he knew that what the president was saying was not true. “It was incredible,” Rolando said. “I turned to my friend and told him to look at my skin. And he said, ‘That is the power of good speech.’”

“Charisma,” Rolando said with a nod. “It is what all dictator’s rely on for power. From Hitler to Chavez.”

By 1980, Rolando’s brother managed to gain passage to Venezuela, which had begun to accept hundreds of ex-Cuban political prisoners. As Professor Holly Ackerman explains in an essay, this arrangement between the two countries was mutually beneficial. Castro was glad to get dissenters out of the country instead of keeping them in the prisons or unemployed in the streets, and the Venezuelan government welcomed the optics of accepting opponents of communism. The Cuban expat community in Venezuela was more than glad to absorb them. Once in Caracas, Reinaldo Martinez hoped his ex-prisoner status would help him obtain visas for the rest of his family, including Norma, as the mother of his nephews.

Norma Fanego’s Cuban passport

And it did. Four years later, he filed family reunification papers on their behalf and sent them money to pay for exit permission fees. Madelin Martinez packed all her belongings in a 12-pound suitcase—less “than you would put in for a one-week trip”—and boarded a plane with her mother, her brother, her father and his second wife, and her widowed grandmother. Before they left, government officials scoured the house to make sure they did not take more belongings than the law permitted. “They counted the knives, the forks, the television,” she said. “They didn’t even let you take your photos, your watch, nothing.”

The decision to relocate was especially difficult on Madelin’s mother. It meant leaving her own family in Cuba. True, she was with her children, but also with the family of the man she had been divorced from for a decade and his second wife. “I would have liked to have left by my own means,” she said, letting the thought trail off with raised eyebrows and a puckered forehead.

At dawn on May 9, 1984, the Martinez family arrived in Caracas. Madelin, by then 17, looked in amazement at the highway billboards advertising Coca Cola, Herbert Compote, and Mavesa Butter. “In Cuba all the signs said “Fidel” or “Martí” or “El Che Guevara,” she said. He first trip to a supermarket made her “dizzy,” she said. “with the amount of food and cans one besides the other.”

By the time the Martinez family arrived, Venezuela was receiving its third of five waves of Cuban émigrés. The community had grown to 13,000 with about 7,000 immigrants arriving during the period between 1978 and 1989. They were mostly former political prisoners and their largely lower middle class relatives. Among them were also some 900 travelers of the Mariel mass migration, which a sharp economic downturn in Cuba propelled in 1980. At that time, thousands of Cubans asked the Peruvian embassy for asylum and Castro allowed anyone who wanted to leave Cuba to do so.

In Caracas, the family moved into the two-bedroom apartment of Reinaldo and his wife in the center of Caracas. Rolando and his new wife promptly found work as janitors in a residential building, and Rolando soon was able to resume his career as a draftsman. Madelin and her mother took jobs as hairdressers at Sandro, a popular salon in the middle-class neighborhood of Chacaito. Through a co-worker, Madelin met her future husband, Javier Belloso, a Venezuelan who owned a computer accessories store.

Norma Fanego’s Venezuelan passport

Life rolled along until 12 years later. Norma Fanego remembered the date, Feb. 4, 1992. She saw Chavez on television for the first time.. This was just before he went to jail for a failed coup against President Carlos Andres Perez. Chavez, wearing a red Castro-like beret, said “Comrades, for now we didn’t meet our objectives…I asume in front of you the responsibility of this Bolivarian military movement.” A year later, Perez’s successor, President Rafael Caldera, released Chavez in a move to differentiate himself from the corruption scandals and unpopular neoliberal reforms of his predecessor. Already there were rumors that Chavez would soon succeed in presidency. Indeed, Chavez visited Cuba in 1994 to start planning his 1998 presidential campaign with Castro’s help.

Norma began to obsess about a Cuban déjà vu and two years later, decided to leave Caracas in 1994, a good four years before Chavez became president. She packed up herself and her son, who was in the thrall of young local drug addicts, and moved to Miami on tourist visas. Once there, without working papers, she began working black, cleaning the floors of salons. Both she and her son were granted residency the following year as part of the Cuban Adjustment Act. Soon after, she passed a hairdresser course and was licensed to resume her profession doing cuts, blowouts and hair color once again.

Norma Fanego’s American passport

Nonetheless, she was consumed with anxiety and bouts of depression. She had several minor car accidents and over the next five years, found it so difficult to concentrate at work that she went disability. “I was in a crisis,” she said. “All I did was cry. I didn’t know where to go. I wanted to go back to Venezuela, I wanted to go back to Cuba.” She mentioned her son and that he died in 2014, when he was in his late 30s. The details were still too difficult for her to discuss. “I have pain inside me. I have struggled with the changes of one country to another,” was all that she would say.