Mefloquine Mondays

Is an Army-developed antimalarial the new Agent Orange?

by Daniel Costa-Roberts

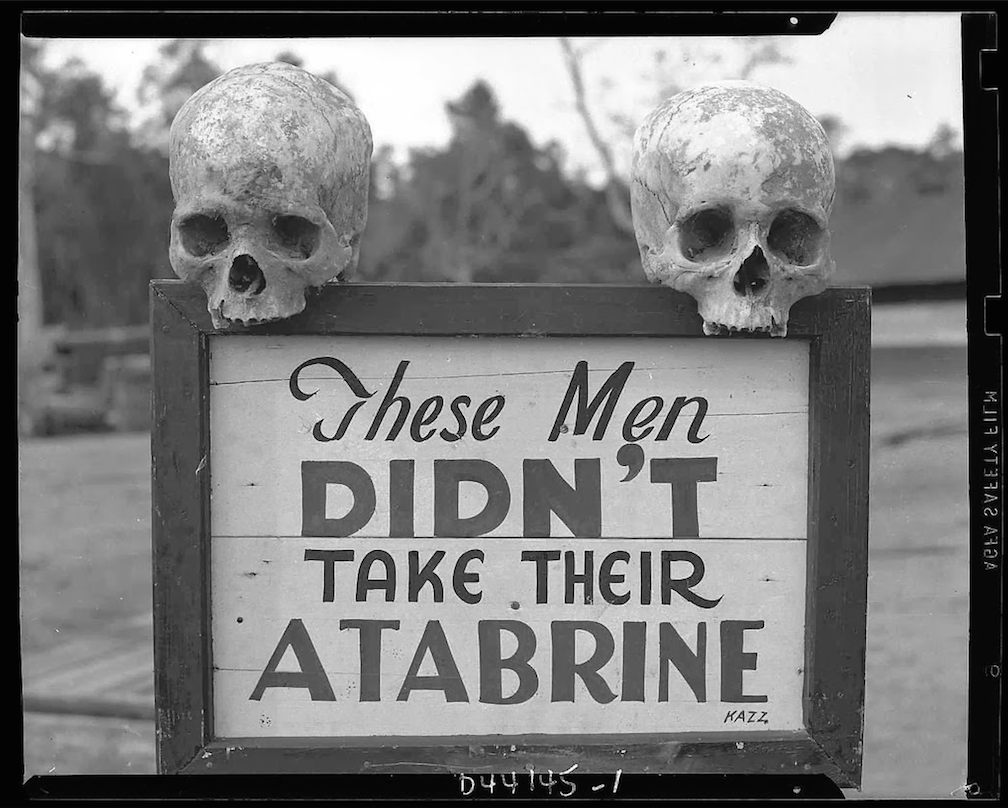

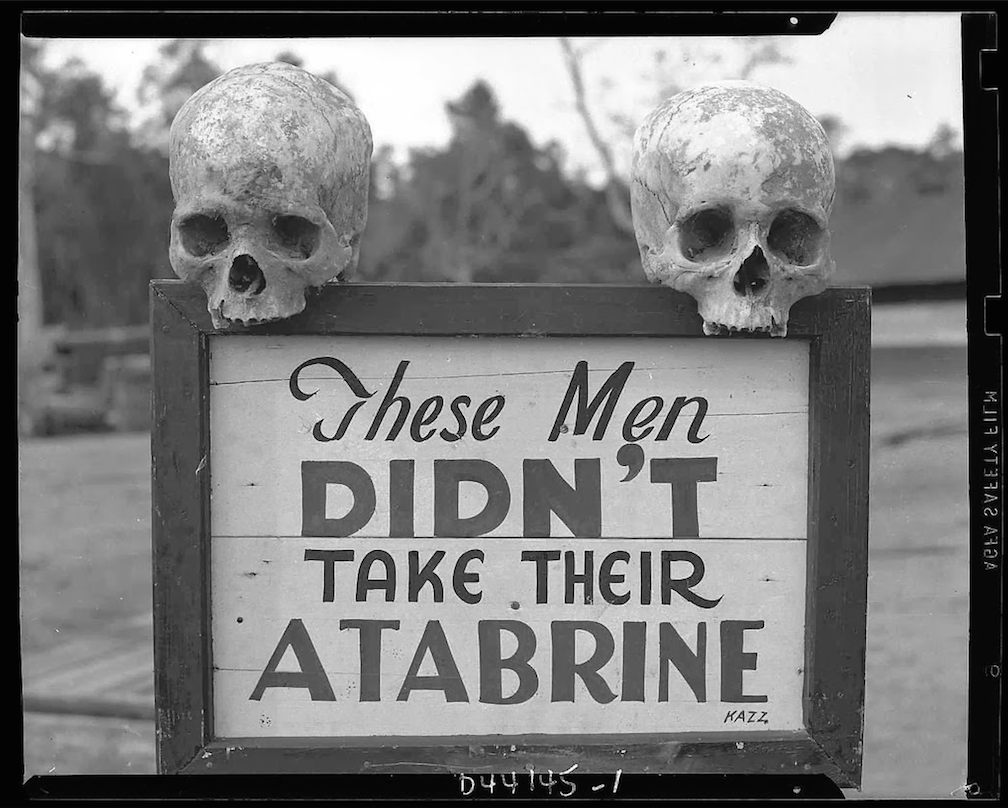

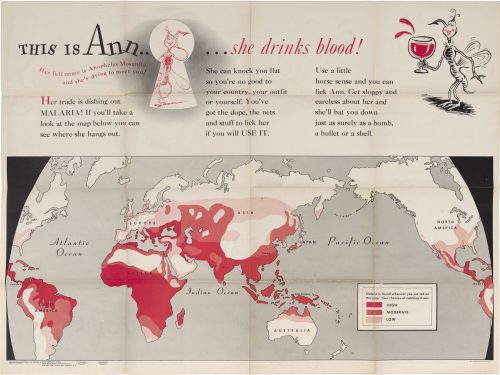

A sign posted at the 363rd Station Hospital in Papua New Guinea during World War II admonishes soldiers to take their antimalarials

The first hint of the crisis that would come to define Capt. Remington Nevin’s career appeared one morning early in January 2007, in the form of an Army medic holding a black plastic garbage bag in his outstretched hands.

The man stood at the exit of Fort Bragg’s “Green Ramp” staging area, where Nevin and the rest of his unit in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division had waited restively to board a jet that would fly them on the first leg of their journey to Afghanistan. As the soldiers filed out onto the runway, each was instructed to grab a packet of meds from the garbage bag. Nevin, the unit’s new preventive medicine doctor, did as he was told when his turn came. Without looking, he reached in and pulled out a cardboard package filled with dime-sized, chalky white tablets of an antimalarial called mefloquine hydrochloride, also known by its trade name, Lariam.

Given how unceremoniously the drug was distributed, the soldiers had no reason to suspect what medical regulators already knew: Mefloquine was a dangerous drug whose range of alarming neurological and psychiatric side effects might even include suicide. Even then, Nevin was aware that Department of Defense rules required the medication to be prescribed cautiously and with close attention to the recipient’s medical history. Yet the label on the package that Nevin plucked from the bag bore another soldier’s name.

Nevin was a recent transplant to the unit—to his chagrin, his insignias were still pinned to his camo fatigues rather than sewn on, the tell-tale sign of an “FNG.” Even had he wanted to, he probably could not have changed the unit’s antimalarial policies, which were decided before his arrival. In any case, he was not especially concerned. What Nevin knew about mefloquine at the time hewed to the Pentagon line, highlighted in a 2002 DoD memo: Rarely, the drug could cause problems and thus should not be given to people with mental health issues, but its effectiveness in malaria prevention outweighed its risks.

Soon, however, Nevin “recognized that even perfectly healthy people could be affected by the drug—that their behavior, personality, mood could be altered. It certainly upset patterns of sleep,” he told me.

While he was in Afghanistan, Nevin began to investigate the drug’s history and the scant available research about it. By the time he left the country, he was “quite convinced that this was a very dangerous drug—that we should not be using it at all.”

In the early 1960s, the emergence of drug-resistant forms of the protozoan that causes malaria rendered chloroquine—then the U.S. military’s mainstay antimalarial—ineffective in many parts of the world, including Vietnam. In response, the Army developed mefloquine and shepherded it through clinical testing.

It gradually became clear that mefloquine was a potent toxin that could cause debilitating and sometimes permanent side effects, but military health care providers continued to issue it to service members en masse, most notably in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military officials repeatedly ignored or downplayed evidence that the medication’s side effects are more common and more severe than they initially believed. And the military flouted its own rules for prescribing the drug, endangering thousands of soldiers and leaving some disabled. These problems persisted until 2013, when the DoD revised its policy and made mefloquine a drug of last resort.

Along with advocacy by Nevin and others, new research about the drug’s risks and side effects likely spurred the change. It may not have played a role in the DoD’s decision, but one recent finding has serious implications for veterans’ health: Symptoms of mefloquine toxicity can closely resemble those of combat-related mental health problems like post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

These similarities can lead doctors to make mistaken diagnoses of PTSD, or to miss the fact that a soldier is suffering from the effects of mefloquine toxicity in addition to PTSD. Nevin has documented more than a dozen such cases. By virtue of granting soldiers disability compensation, the VA has even given de facto acknowledgment in a few cases. Yet the number of veterans whose PTSD or similar diagnoses were either caused or exacerbated by taking mefloquine is unclear. Some important data simply do not exist—many soldiers’ mefloquine prescriptions were never recorded, for instance. The Pentagon has declined many requests to release other vital information, such as whether veterans who took the drug have higher rates of PTSD. In doing so, the military has made it nearly impossible to determine the scope of the veterans’ health problem posed by mefloquine-related brain damage, which Nevin believes is “the third signature injury of modern war.”

For armies in malarious areas, drugs that prevent and treat malaria are almost as important as fuel, food, or bullets. Without them, soldiers die.

“The history of malaria in war might almost be taken to be the history of war itself.”

Since antiquity, malaria has marched with armies and killed soldiers, often shaping history in the process. Alexander the Great may have succumbed to it. Historians speculate that Attila the Hun’s fear of exposing his armies to a city rife with malaria stopped him from sacking Rome in A.D. 492. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. Grant all suffered from the malady. It has been such a constant feature of human conflict that a British Royal Army doctor once wrote—with only slight hyperbole—that “the history of malaria in war might almost be taken to be the history of war itself.”

When the U.S. Army’s Medical Department was formed in 1775, scientists had little understanding of the germ theory of disease, much less the specific causes of malaria—then referred to by names like “intermittent fever,” “marsh fever,” and “ague.” And although the characteristic progression of violent chills, scalding fevers, vomiting, headaches, profuse sweating, delirium, and sometimes even death was all too familiar, little was known about how to prevent it. However inadequate, the prevailing wisdom in 18th-century preventive medicine was to urge troops to avoid miasmic vapors found in swamps and bogs, particularly during spring and late summer.

In 1820, two Parisian chemists isolated quinine, the first effective antimalarial. Sixty years later, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, a French army surgeon, discovered Plasmodium protozoa in a patient’s blood and identified them as the cause of malaria. In 1897, a British doctor named Ronald Ross demonstrated that mosquitoes transmitted Laveran’s parasite. Knowing malaria’s cause and manner of transmission gave scientists the information they needed to find effective new ways to fight the disease. The epochal significance of Ross’ breakthrough moved him to verse:

With tears and toiling breath,

I find thy cunning seeds,

O million-murdering Death.

I know this little thing

A myriad men will save.

By the early 20th century, the United States, and the Army in particular, had moved into the world lead in the study and control of malaria, forced, in part, by the disastrous spread of malarial infection among Panama Canal workers. The Army transferred Col. William Crawford Gorgas, a physician, to the isthmus. Gorgas had done pioneering work to curb yellow fever in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. When Gorgas began his work in 1906, some 26,000 people were employed on the canal project. That year, malaria sent about 21,000 of them to the hospital—more than 80 percent of the workforce. Gorgas had the swamps drained to control mosquito populations and instituted a mandatory twice-daily ration of 150 milligrams of quinine per worker. By 1912, he had reduced the hospitalization rate to 1.6 percent—a feat so staggering that a contemporary referred to it as “a chapter in human achievement for which it would be hard to find a parallel.”

Even with these breakthroughs in the understanding and management of malaria, the disease still posed major problems in later American operations abroad.

World War II was a particular case in point. From the Philippines to Sicily, malaria ravaged U.S. troops. In the South Pacific, the disease caused eight times more casualties (a term that describes both deaths and injuries) than did combat.

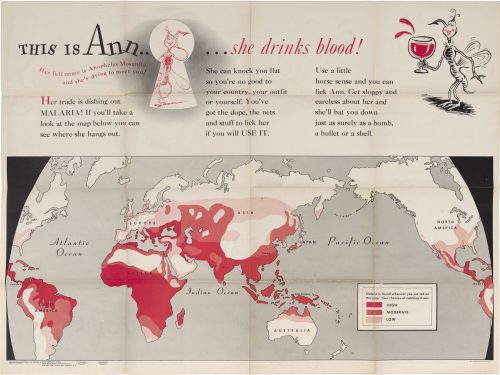

A 1943 Army malaria-prevention illustration created by Theodor Geisel, later known as Dr. Seuss

In desperation, the United States embarked on a search for antimalarial drugs, eventually settling on quinacrine, a compound that German chemists had invented in the early 1930s. Quinacrine (brand name Atabrine) was moderately effective and helped the Allies control malaria rates. Ultimately, however, problematic side effects forced the Army to develop alternatives. Soldiers who took quinacrine experienced headaches, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, nightmares, and even psychosis. The drug—which was originally developed as an industrial dye—also had a tendency to turn their skin and eyes yellow.

As evidence emerged during the war demonstrating how common the negative effects of the drug could be, the military’s reaction foreshadowed how, decades later, it would respond to mefloquine. The military restricted information about the drug’s side effects for the duration of the war. A 1944 Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery newsletter—described by Nevin as a publication “containing information and signed official recommendations which should be considered doctrinal”—said only that “psychological disturbances occasionally appear” in users, and that the quinacrine could cause “mild excitement” and, rarely, “acute maniacal psychoses.”

As the war ended and American GIs left malarious areas, the Army’s drug discovery program continued. By 1947, it produced an alternative called chloroquine. Although it was chemically related to quinine and quinacrine—all three belong to the family of quinoline derivatives that also includes mefloquine—it was thought to be safer and more effective than the other two.

For the next decade or so, chloroquine worked well in protecting American troops stationed abroad, until a deadly form of the malaria parasite developed resistance to the drug. By 1961, it was infecting American soldiers stationed in Vietnam and had spread across Southeast Asia. Again, the military founds its main weapon against malaria useless; again, it initiated a frantic drug development push.

In 1961, scientists at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research embarked on the costliest drug search ever mounted to date, a titanic undertaking in which Army researchers collaborated with a host of governmental agencies, academic organizations, and companies, including 175 external contractors. By 1968, they were screening up to 1,000 chemical compounds every month, to little effect. None of the hundreds of thousands of drugs they tested had proven safe and effective. Meanwhile, 9,000 miles away, American soldiers remained vulnerable.

The program bore fruit a year later. The researchers found a compound—then known only by a Walter Reed experimental number, WR 142490—that worked against the parasite and was not unduly toxic. The drug, later named mefloquine, seemed like a godsend.

At some point in the 1970s—the details are obscure, having never been made public—the DoD started collaborating with the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Hoffman-La Roche. The two entities soon began the testing needed to bring the drug to market.

Initial published reports were glowing. Early testing revealed little in the way of serious adverse reactions to the drug.

Although the apparent absence of toxic side effects was seen as encouraging, hindsight suggests this was not evidence of drug safety, but rather of insufficient research. Mefloquine was tested less extensively than most pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ashley Croft, a former British Army physician and a prominent critic of mefloquine’s use has noted the drug’s clinical trials were rushed, and that researchers ignored danger signs.

Nevin knows this story well. He has been as central to mefloquine’s recent history as anyone alive. Had he been born three decades earlier, he might have been part of the cohort of Army doctors who developed and tested the drug. But instead, Nevin was born in Canada in 1974, the son of an American draft-dodger who fled North to avoid the very war that gave rise to mefloquine; and he has has done most of his mefloquine-related work as a civilian. Nevin ended his 14-year career with the Army in 2012 and enrolled in public health doctoral program at Johns Hopkins University. He has made a relentless, almost obsessive study of the drug and its effects ever since, but he didn’t plan it that way.

Nevin’s future in the Army had been promising. He was a top preventive medicine student in medical school—he won an award for it—then a top preventive medicine resident. He was given a distinguished first assignment. People told him he’d be Army surgeon general one day, although he modestly says he thinks they were exaggerating. “I had a nice corner office. Life was very good. I hired half a dozen staff to work for me,” Nevin told me.

By the end of his deployment to Afghanistan, that had all changed. While he was there, he got a look at how military health care works in practice. It was much more troubling than the view from his corner office just outside the Washington, D.C. Beltway. A number of things he saw in Afghanistan troubled him, the Army’s mefloquine practices important among them. He spoke out. “By the time I returned home from Afghanistan, of course, you know my career prospects had taken a turn for the worse. I realized I’m probably not going to be serving a career in the military,” Nevin told me.

He also began to see mefloquine as a serious, unacknowledged threat to soldiers’ health, one that he felt uniquely positioned to confront. “You are just in the wrong place at the wrong time—or the right place at the right time,” he said, “where an issue lands in your lap and you realize there is really no one else that can address this as well as you can at the moment. And it becomes your responsibility.”

A picture of Nevin that appears on his website

Nevin has published dozens of scientific articles about issues related to mefloquine, research that has made him the most prominent American scientist in the field. He has also chronicled the drug’s effects on dozens of people, many of them veterans, and is often retained as an expert witness in trials involving mefloquine. He has also appeared before Congress and the British House of Commons, urging lawmakers to restrict the drug’s use.

Nevin has become something of a niche media darling. A quote from him is almost perfunctory in news stories about mefloquine. Quite apart from his articulateness and professional distinction, he makes an impression with his booming voice, salt-and-pepper beard, and distinctive manner of dress—several open buttons often leaving a triangle of chest hair on roguish display.

Nevin has doggedly investigated the military’s mistakes regarding mefloquine policy and development. In his account, lack of adequate clinical testing was mefloquine’s birth defect, the first of many mistakes leading to the considerable harm it has caused.

The rush through Walter Reed and Roche drug trials meant no normal preclinical animal testing took place. This was an oversight, Nevin said: Scientists knew that other members of mefloquine’s chemical family had toxic effects on the brain, so it would have been logical to check whether mefloquine did, too. Instead, researchers moved quickly to Phase I, the first of three stages of human testing that medicines undergo in the hope of Food and Drug Administration approval.

“The problem with mefloquine is that the preclinical testing was clearly incomplete based on what should have been known about its mechanism of toxicity,” Nevin wrote in an email. Dizziness and other common side effects that the researchers identified as early as the first testing phase “were not fully characterized as being related to CNS toxicity,” he said, using the acronym for central nervous system. “A more detailed search for CNS effects was therefore not performed.”

Had researchers looked more closely during Phase I, they might have realized that a considerable number of the study’s subjects suffered such symptoms as nightmares, insomnia, and anxiety, whose origins all lay in the central nervous system. Had things gone differently, the drug might never have made it to the second testing phase. But the researchers assumed the side effects were short-term and not indicators of permanent brain damage.

Nevin finds it incredible that the drug passed Phase I. “It very likely took significant effort to intentionally overlook or ignore the side effects that were undoubtedly occurring during these early study stages,” he said.

In the course of reporting this story, I tried to speak with many of the important figures involved in mefloquine’s development. Many have died. Of those contacted who could have responded, all either declined to comment or never replied to repeated messages.

Roche never undertook conventional Phase III testing, which typically involves randomized, blinded trials involving large numbers of human subjects. The company may not have had much choice in the matter, however, since there were no good alternative malaria drugs against which to compare it at the time. This was, of course, why mefloquine was developed in the first place.

European regulators approved mefloquine in 1985 and the FDA followed four years later. During those years, adverse effects were reported. Roche and the World Health Organization received dozens of reports from European physicians who described troubling symptoms that they saw patients prescribed mefloquine. In 1992, the WHO and Roche released a joint review of all such reports they had received between 1985 and 1990. They listed physical and mental side effects that had been observed, such as aggression, psychosis, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, paranoia, hallucinations, anxiety, and unusual dreams. Notably, the document went so far as to say that “some of the neurological and psychiatric events reported were severe and alarming.” The report also pointed out that 2 percent of the patients experienced “longer-term” issues. It was only years later that Roche included mention of possible chronic problems on the drug’s product information.

The WHO carefully noted that there was no proof that mefloquine caused the reported events, and that available research into the drug’s effects was “too preliminary to warrant radical changes in international guidelines.” But it did put out interim instructions warning certain groups not to use the drug, including people operating machinery and those who relied on their fine motor coordination, citing airline pilots as an example.

At the time of licensure in the United States, drug regulators may have been hesitant to withhold approval of the era’s most effective antimalarial, especially on the basis of preliminary accounts of putatively rare, usually transient side effects. It is clear, however, that Roche and the WHO knew that mefloquine users were reporting dangerous, occasionally persistent side effects at the time the drug was cleared for use in the United States. The WHO had even warned some users against taking it.

U.S. approval of mefloquine made it the antimalarial of choice among American civilians in the 1990s, when Americans were filling thousands of prescriptions for it daily, especially those traveling to the tropics. The surge in prescriptions meant a like increase in the number of unpleasant reactions, including occasional reports of Americans who became psychotic while traveling. This, in turn, prompted doctors and reporters to scrutinize the drug more closely, and evidence of the drug’s dangers began to accumulate. But the American public remained largely unaware.

September 11, 2001 set in motion events that changed that. As American troops deployed to Afghanistan, and later, Iraq, many were issued the chalky white tablets. More American service members were taking the drug than ever before, and a succession of media reports about mefloquine’s use in the military soon gained national attention. One of these involved Staff Sgt. Georg-Andreas Pogány, whose story I pieced together from medical case studies, my interviews with Pogány, a July 2004 Gentleman’s Quarterly story, and other news stories.

In late September 2003, Pogány, an Army human intelligence collector, deployed to Iraq, where he and his 12-man Special Forces detachment were stationed in an abandoned house in the city of Samarra. Just days into the tour, he lost his mind.

The ordeal began on the night of Sept. 29, his third day in country. Pogány jerked awake from an intensely vivid nightmare—he dreamed that the room he slept in had erupted into an inferno—and was convinced that his unit was under attack. He quickly grabbed his weapon and slung on his combat gear, believing that the enemy was breaking into the room. Panicking, he began a tactical search of his unit’s sleeping quarters. He saw ghastly, harrowing things as he swept from room to room: mangled corpses lying in the beds where his unit members belonged; Iraqi prisoners, their hands bound, kneeling beside a man with a gash running half the length of his leg; his own mutilated remains staring up at him from a body bag.

At this point, Pogány began to suspect that he was hallucinating. He returned to his bed and lay down, anxious and unable to sleep. He vomited. He trembled as he watched phantasmic shells burst through the ceiling and cave the room in. Time crawled by at a pace much slower than in reality. He vomited again and again until morning. Two days earlier, he had taken his third weekly dose of mefloquine.

In medical parlance, mefloquine is an idiosyncratic central nervous system toxicant whose effects are heterogenous. Jargon aside, this is a revealing phrase. The term “heterogeneous” refers to mefloquine’s incredibly diverse side effects, which include sores in the mouth, upset stomach, extreme sensitivity to light, insomnia and abnormal dreams, permanent vertigo, personality changes, and unwarranted, violent feelings of rage—or even actual violence. (There are also strong suggestions that the drug leads to suicide, although Roche does not acknowledge a causal link.) “Idiosyncratic” simply means that, for unknown reasons, some people react negatively to the drug while others do not. People of similar age, build, medical history, and health can take the same dose of mefloquine and have totally different reactions. Some use it without incident; others, like Pogány, become psychotic after the third dose. On these rare occasions, mefloquine madness can be extraordinary.

Nevin described the phenomenon in a 2013 Huffington Post article:

In a grip of such a terrifying psychosis, victims have jumped from buildings, or shot or stabbed themselves in grisly ways reminiscent of scenes from M. Night Shyamalan’s film “The Happening.” Those who have survived mefloquine’s psychotic effects describe experiencing morbid fascination with death, eerie dreamlike out-of-body states, and often uncontrollable compulsions and impulsivity towards acts of violence and self-harm.

This was likely the case for a 27-year-old French citizen whose almost unimaginably macabre suicide was chronicled in a 2010 case report. In the final weeks of his life, the man had taken mefloquine before flying to Africa. Soon after he returned to France, his naked corpse was found on the floor of his apartment. Photographs of the scene show his slender form lying in graceful repose on the checkered carpet. Both are soaked with blood, as is the handle of a kitchen knife that lies near his body, its blade snapped clean off—the autopsy found it lodged in his temporal lobe.

The man had no history of mental illness, and blood and urine samples showed that the only drugs in his system were mefloquine and chloroquine. The circumstances of his death led the authors of the report to record their “very strong presumption” that mefloquine either caused or contributed to his demise. Apart from the rarity of healthy people committing suicide was the exceedingly unusual way he died. Only about 3 percent of suicides involve sharp objects, and virtually none of those feature stab wounds to the skull. The study reported that fewer than 30 such cases have been documented since 1928, and these mostly involved mental patients and prisoners. Equally disturbingly, the autopsy detailed eight significant wounds on the man’s body. Of these, the study authors wrote, “none were associated with tentative wounds,” meaning they showed no evidence of hesitation.

The morning after Pogány’s episode, he told his team sergeant that he was freaking out, that he was afraid he was having a nervous breakdown. The sergeant thought that he was just reacting to the stress of deployment. In the days since his arrival in Iraq, the strain had been considerable. He had seen the shredded corpse of an Iraqi torn apart by machine gun fire, and with his unit, sweating in the heat of noonday Iraq, spent five harrowing hours exposed and helpless at a dangerous intersection when a vehicle in their convoy broke down. The man told Pogány to pull his head out of his ass and refused his request to be sent somewhere for treatment. All that day, Sept. 30, Pógany kept hallucinating. He heard muffled voices plotting to kill him. As he talked with his team members, he saw them as skeletal remains.

Eventually, Pogány told the sergeant he couldn’t go on. He insisted on treatment, even if it meant sending him home. The sergeant tried to dissuade him, saying he’d give Pogány until lunchtime to make up his mind. Pogány kept insisting he was not all right. It was only then that sergeant confiscated Pogány’s weapon and confined him on suicide watch until he could be transferred for evaluation. As he awaited this assessment, he was repeatedly told that he had two choices: Return to his duties as normal or face legal charges for refusing orders.

Eventually, Pogány was moved to a base in Tikrit, about 50 miles away. The journey there, in an armored convoy, was dangerous. Just that morning, another convoy had been attacked along the very same route. Pogány wanted his gun back for the ride, but was told he couldn’t have it.

Things started happening quickly: Pogány was confined at the base and told to stay away from the other soldiers, apparently because his superiors thought he was a coward. He met with an Army psychologist, Capt. Marc Houck, who believed Pogány was having a combat-stress reaction, a normal response to the psychic strain of war. Houck recommended local treatment—Pogány should be removed from his duties temporarily, taught coping techniques, and allowed to rest for a week or so before going back to his unit. Instead, he was put on a plane to the United States, where he would be treated like a criminal.

Pogány’s wife was told not to show up to welcome him home when he landed on Oct. 7, just a week after his meltdown. Instead, two soldiers were there to greet him when he got off the plane. The men searched him, took away his knife, computer, and phone, and later his personal handgun. Another week later, the Army charged him with cowardice, a very serious, highly unusual accusation which the Army had not made against a soldier in 35 years. It was punishable by death.

The Army did not execute Pogány for his alleged crime. Instead, it dropped the charge after a month, offering no explanation of why it had done so, and accused him of a lesser offense: dereliction of duty. By this point, in November 2003, Pogány knew mefloquine had caused his ordeal. The knowledge was a relief—it meant he hadn’t simply broken under pressure; he wasn’t a coward—but it did not immediately help his legal case.

The Army initially rejected the possibility that mefloquine had played a part in his breakdown, challenging the claim on the basis that there was no documentation proving that Pogány had received the drug. When he produced leftover tablets that he still had, the Army conceded that he had taken mefloquine, but refused to accept the exposure as a legal defense.

Another month passed, and the Army abandoned the dereliction of duty charge, offering a plea bargain, which Pogány rejected. He wanted a trial, which would allow him to demand explanations publicly. The Army demurred. Over the next several months, while the Army considered additional charges, Pogány underwent a series of medical tests. He was diagnosed with PTSD; military doctors confirmed that mefloquine could well have caused the psychological symptoms he experienced in Iraq; a specialist determined that he had a vestibular injury affecting his balance as well as nystagmus (a condition in which the eyes move involuntarily), both likely results of brain damage caused by mefloquine toxicity.

In July of 2004, the Army dropped its case against Pogány entirely, apparently because it decided mefloquine had played a role in his breakdown. At the time, a Special Operations spokesman told United Press International, “Additional information became available over time that indicates that Staff Sgt. Pogany may have medical problems that require treatment. Our primary concern is the health of Staff Sgt. Pogány.”

Pogány was medically retired from the Army in 2006 for the vestibular injury, but the military remains a presence in his life. There’s still something of the soldier in the way he communicates (Pogány described an Army official as having “a hard-on for the guy” to mean that he bore someone a grudge, and he scheduled interviews with me for times like 14:15, using the military’s 24-hour time format). And he still works with service members, serving as CEO of the Uniformed Services Justice Advocacy Group, a nonprofit that advocates and provides legal services for veterans.

Some physical problems like vertigo and sensitivity to light still plague him, and he has some odd cognitive problems—when he types, his fingers often press a different button than the one his brain intended, for instance. But his psychiatric symptoms have mostly dissipated and his health is generally good. And if it were not for his reaction to mefloquine and all that followed, he thinks he would have ended up in a different line of work, and wouldn’t have helped the hundreds of service members whom he’s worked with since leaving the Army.

For all the nightmarish quality of Pogány’s mefloquine reaction and the Army’s response to it, he has the consolation of being mostly unharmed; the experience even gave his life purpose in many ways. Other mefloquine veterans aren’t so lucky in either respect: Many experience debilitating long-term effects, a fact the Department of Veterans Affairs has acknowledged by granting disability pay to several veterans affected by the drug.

Pogány’s experience garnered considerable media attention, unlike many other veterans, like Dylan Cole, who have experienced similar ordeals and still live with chronic effects of the drug. Cole’s mefloquine story began in 2008, when he and the other Marines in his unit started taking the medication a week before they deployed to Afghanistan’s Helmand Province.

“I haven’t got a full night’s sleep since the day I took that pill.”

In a photo from the night he deployed, Cole, now 29, looks confident and healthy, but the drug was already having an effect. As in Pogány’s case, vivid dreams were the first effect he noticed. Scientists now recognize this reaction as more than a side effect of the drug. They call it a “prodrome” of mefloquine toxicity—in other words, a harbinger of worse to come. The instructions that Roche sends with prescriptions of Lariam notes that insomnia and vivid dreams are a “very common” side effect, meaning they affect more than 10 percent of those who take mefloquine, and that depression or anxiety symptoms can occur in between 1 and 10 percent of users. Some research suggests the frequency of these prodromal side effects may be close to 30 percent. As late as 2009, however, Pentagon guidelines continued to state that the risk of psychiatric symptoms was “1 per 2,000-13,000 persons,” a statistic that makes the problem appear hundreds of times less common than current research suggests.

“They start pretty much once you take it,” Cole said of the dreams. The literature and interviews with soldiers indicate these reactions are commonplace enough for service members gave nicknames to the days when they took their weekly dose, when the effects was particularly intense. Some units had Psycho Tuesdays; others had Wacky Wednesdays. Cole and the men he served with took their pills on Mondays. “We all made jokes,” Cole told me. “Mefloquine Monday—what crazy dreams will we have tonight?”

Eight years on, the humor has worn off, but the sleep problems persist. Even over the phone from his native Pittsburgh, his voice has a croaky, weary edge to it. “The dreams, that just never stopped, even after I stopped the medication,” he said. “That irritability of it—like if you don’t sleep, you get very irritable and with those dreams like that you’ll wake up all the time. “You never get, like, a full night’s sleep. I haven’t got a full night’s sleep since the day I took that pill,” Cole said. Later, he told me, “the only thing I found helped was drinking. That’s the only time I’d get a solid four or five hours of sleep.”

Cole said anyone given to nightmares would find them intensified after taking the drug, but most of the time “it’s just everything is off-the-walls crazy—crazy dreams. Not always, like, horrible, horrible things, but it’s always crazy and vivid like you’re awake.”

Dylan Cole (right) poses with his friend the night before they deployed to Afghanistan

This verisimilitude, which is sometimes described as “hyperrealism, or “technicolor clarity” in the literature, can be unnerving long after waking up. Cole said his dreams are so vivid that he sometimes has to think hard to distinguish reality from what he imagines as he sleeps. “There’s times I’d wake up and have to sit there and think about it for a minute—‘did that happen or not happen?’”

Not all mefloquine dreams are terrifying; Nevin’s certainly weren’t during his Afghan deployment. During an interview in his Johns Hopkins office, he described what he experienced in his sleep as wonderful and enjoyable. He dreamed that he was a rock star, he told me, with a slightly sheepish grin that seemed to hint at visions not purely musical.

Cole and others who experience strange dreams and interrupted sleep may never return to normal. Summarizing a recent study of people who reported adverse reactions to mefloquine, Nevin told me, “Roughly a quarter of those folks who were troubled with nightmares are still reporting nightmares three years later. And presumably, those nightmares will last forever at that point. That’s a chronic, permanent problem.”

Brian Estill’s experience with the drug has been perhaps the most debilitating of all the mefloquine veterans I talked to.

Estill comes from a military family. One of his grandfathers served in the Army and the other in the Marines. His dad was an Army man, too—Estill was born on a U.S. Army base in Germany, and he and his four siblings spent their childhoods bouncing around Europe and the American South as Army brats. He joined the Marine Corps in 1994, right out of high school. Frank Estill, himself an Army veteran, says the family was proud of his little brother. Brian was a golden boy: He was a talented high school football player and he was popular. “Us normal guys we’d chase girls, you know. But the girls would just come to Brian naturally, so we were all jealous,” Frank told me, laughing.

Like his brother, Brian Estill is kind, soft-spoken, and friendly, with manners that match his Southern accent. But he gets agitated when he talks about mefloquine.

“I was an outstanding Marine,” he told me, exasperated. His future with the Corps certainly seems to have been bright. He was meritoriously promoted. A Navy achievement medal he received in 1995 cites a long list of his soldierly virtues, including “exceptional professional ability, initiative, and loyal dedication to duty.” It also commends his “exceptional mental and physical stamina.”

Those superlatives no longer applied to Estill just one year later. The mefloquine that he took while deployed left him physically uncomfortable—the anxiety he suffers can feel like a heart attack, like an “elephant sitting on my chest.” It robbed him of his sharp mind, too. And when it comes to the Corps, he certainly doesn’t feel any sense of semper fi.

In 1996, the Navy’s USS Guam was rerouted away from its scheduled operations and sent to Liberia, where it was stationed off the coast to assist in Operation Assured Response, part of an effort to protect the U.S. embassy in the capital city of Monrovia.

Estill was on the Guam and he was given mefloquine to protect him from malaria, which plagues West Africa.

His whole unit was prescribed the pills, he told me. “We were all given mefloquine, and we all reacted differently to it,” Estill said. He thinks more than half of them suffered from side effects.

He noticed the effects after his very first dose. “I just had all these strange things come over me,” he said. “I got emotional. I had to hide. You know, there’s 2,000 people on the USS Guam and I couldn’t be around none of them. I had to find a hiding place—I just felt like I needed to hide; I needed to cry; I needed to—just all this weird shit was comin’ up to the surface and I didn’t know how to deal with it, man.”

Now, 20 years later, daily life is hard for him. He struggles with a range of effects like depression. He’s attempted suicide twice; some days are better than others, but the desire to try again is often with him. “I’m still suicidal. I’m still depressant. I’m still scatterbrained,” he said. “Man, I’m still fucked up from it.”

For 12 years after leaving the Marines in 1997, he tried cope alone, avoiding visits to the VA until 2009, when he finally sought help. At that point, he said, “I was getting ready to kill myself, man. I was so close. I almost feel like that right now.”

He receives 50 percent disability pay from the VA: In 2009 a doctor there diagnosed him with a “substance-induced mood disorder,” and they’ve given him a range of pills, including lithium and antidepressants. Nothing has helped much.

A masonry mosaic that Brian Estill made to depict the feelings that mefloquine causes him. He calls the piece “Mefloquine Mars.”

Several times during our interviews, Estill trailed off with a phrase like, “That’s all—I can’t remember anything else, man.” He has trouble remembering small things, like the name of his VA-prescribed antidepressant, and also crucial moments in his life. At points he talked faster, his voice raised. “Still to this day, I can’t remember my kids being young. I just—sometimes I walk around in circles in my apartment ‘cause I don’t know what to do, I don’t know what to do next,” he said. “I’m a mess, dude. And I blame it on Lariam; I blame it on mefloquine. Fuck this shit.”

Despite the range of mefloquine reactions that Remington Nevin, Georg-Andreas Pogány, Dylan Cole, and Brian Estill experienced, and the different ways their lives have changed since taking it, one thing unites their experiences: All the veterans I spoke with say they were given mefloquine with a similar lack of oversight and failure to observe rules about how the drug should be prescribed—rules that existed to prevent serious adverse effects. Not in every case was the abuse of policy as flagrant as it was when Nevin was given another soldier’s prescription, but almost every soldier interviewed recalled a similarly lax distribution model. In two recountings, groups of soldiers were handed handed Ziplocs full of loose mefloquine tablets.

Dylan Cole says that the Monday before he and the other Marines in his unit deployed to Afghanistan, they were told to gather for a meeting about mefloquine. “They had a little auditorium on base and we all went to a little meeting about it and there was a paper coming around that said, ‘the doses they want to get you is not FDA-approved,’” Cole told me, adding that the dose they were asked to sign off on was twice the standard 250 milligrams. The risk of adverse reactions to mefloquine is greater at higher doses. “I didn’t sign it. I just handed the paper on and refused to sign it. I didn’t say anything because they would’ve made me sign it. But they still made me take the medicine.”

None of the soldiers I interviewed was properly informed about mefloquine’s side effects or told to stop taking the drug at the onset of prodromal symptoms. Pogány told me that for weeks after his breakdown in Iraq, he kept taking mefloquine because he had no idea that it was to blame for his symptoms. He simply thought he was losing his mind.

Cole says he was given very little information about the drug he was asked to sign off on. “It’s not like when you go to the doctor and they tell you, like, the prescription you’re getting, the side effects, or what it’s for and all that,” he said, referring to dealing with the Corps medics who handed the drug out. “They told us it’s so we don’t get malaria” and mentioned vivid dreams. But they brought the dreams up only as a likely side effect, not as cause for concern. He laughed derisively when I asked him if he was informed of any circumstances under which he should discontinue its use. “There was no option to stop taking it,” he said.

In a period of less than six weeks during the summer of 2002, there were five spousal homicides at the Army’s Fort Bragg base in North Carolina. In two of them, the soldier involved also killed himself. It is likely that three of the men took mefloquine while deployed to Afghanistan, although the Army report only definitively lists two as having done so. So many murder-suicides, committed in rapid succession on the same Army base, naturally became a national news story and the Army quickly dispatched a team to investigate.

In its report on the cluster, the Army epidemiological consultation—or “EPICON”—team dismissed mefloquine as a factor in the slayings, without much apparent effort to investigate the connection. Instead, the report cited marital discord—exacerbated by issues like the stress of frequent deployments and flawed support systems for soldiers and their families—as “a major factor” in the deaths. The investigation ignored the fact that none of the soldiers involved had a history of domestic violence before they started taking mefloquine. Spouse-on-spouse murders rarely happen without a pattern of earlier abuse.

According to Nevin, his former boss, Col. Robert DeFraites, who oversaw the investigation, influenced the investigators to ignore mefloquine as a possible contributor. “He already determined from higher headquarters that they could not conclude the mefloquine role. They never actually investigated that. It was understood that they were not going to accept that as a conclusion,” Nevin said. “So the results of the investigation in this context are meaningless because they didn’t do the investigation.” DeFraites declined to be interviewed for this story.

Dr. Elspeth Ritchie, who is now retired, served on the Army team that investigated the Fort Bragg cluster, representing the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs as a subject matter expert. Ritchie’s account of the team’s investigation departs from Nevin’s. The two have often co-written studies on mefloquine’s mental health effects, but Ritchie says that in this case, as they often do, they disagree on one theme. Where Nevin sometimes perceives a concerted military effort to hide evidence of mefloquine’s harmful effects, Ritchie’s versions of events tend to be less sinister. “The brief version is he sees conspiracy; I see incompetence,” or other shortcomings caused by human fallibility rather than malice, she told me.

For example, Ritchie does not see any evidence of a cover-up, of an Army conspiracy to pressure the EPICON team into leaving mefloquine out of its report. “I can’t say it didn’t happen,” she said, “but I think the bulk of the team, you know—we looked at everything pretty closely.”

She does indicate some bias, however, in the team’s lack of findings on any link between mefloquine and the spate of killings. “There probably were biases against finding mefloquine as a cause. I’m not sure of the reason for the biases. Certainly we were not told” not to investigate such a connection, Ritchie said. “But I think the bias was towards finding problems with, for example, access to mental health care.”

As new evidence of the drug’s effects has emerged, Ritchie does now think it may have played a greater role in the cluster than its dismissal in the 2002 report would indicate. For example, the EPICON investigators knew that one of the dead Fort Bragg soldiers, Sgt. 1st Class Rigoberto Nieves, had taken mefloquine six months before—having just discovered his wife’s infidelity—he pulled a pistol out of his nightstand and shot her and then turned the gun on himself. What no one definitively knew until researchers demonstrated it two years later, however, is that mefloquine can permanently damage brain cells, causing side effects that may persist well after the drug leaves a user’s body. Without that key piece of information, it was much harder to implicate Nieve’s mefloquine use in what otherwise looked like a textbook murder-suicide dynamic.

“So at the time,” she said, “it didn’t seem like mefloquine was a contributing factor. For me what’s happened is over time, I’ve learned more about mefloquine, and in retrospect, I do think it was a contributing factor” in several of the cases.

In the military’s ubiquitous alphabet-soup shorthand, prescription drugs like mefloquine are called FHPPP—force health protection prescription products. As early as 2003, Defense Department policy made strict stipulations about FHPPP, which still apply today. Only qualified medical providers who have received instruction about how to issue such drugs—and when not to—can give them out. They have to do so with written prescriptions, which must be documented in the recipient’s medical records. And providers are required to report any adverse events that patients inform them of. These requirements reflect existing Roche product information and guidelines from the CDC and FDA.

The Fort Bragg EPICON team expressed concern that mefloquine was not consistently being prescribed properly to soldiers. As a side note in its report, the team wrote:

One of the concerns raised regarding mefloquine use by active duty personnel at Fort Bragg was the reported inconsistency in the medical documentation and risk communication during the prescription process. This factor, coupled with inconsistent screening of individuals who may be at increased risk for neuropsychiatric side effects, does not meet prescribing standards according to CDC guidelines or the latest drug company warnings/package inserts.

This problem, however, was not isolated to Fort Bragg, or even to the Army. Although Army personnel constituted the majority of U.S. service members given mefloquine, administration of the drug in the Navy and Marines Corps was little better.

Nonetheless, in early 2004, a senior military medical leader told Congress that the Pentagon was meeting all these guidelines. Dr. William Winkenwerder, who was the assistant secretary of defense for health affairs, confirmed to a House Armed Services subcommittee that FDA guidelines for using the medication were being followed. “Every service member is screened and receives information about possible side effects before taking the product,” he testified. “That is our policy, and that is what should be done.”

Winkenwerder went on to say that a study he had ordered was underway. It would assess the frequency of adverse events, including suicide, associated with the drug. “Hopefully,” he said, “we will get some answers to some of the concerns that have been expressed.”

The study seems never to have been published. Before and after Winkenwerder’s testimony, Nevin told me, the Pentagon has continued “routinely prescribing the drug ‘off label’ to those with contraindications, or continuing to compel its use in service members suffering and reporting prodromal symptoms.”

While Nevin was still in the Army, he published the results of a review of the medical records of a group of U.S. military personnel who had deployed to Afghanistan in 2007, as he had. The study’s question was straightforward: How many of these service members were given mefloquine even though they had mental health issues that should have barred such prescriptions? His conclusion was damning: One in seven service members with “neuropsychiatric contraindications” received a prescription for mefloquine, a systemic failure that Nevin said left those soldiers in much greater danger of suffering adverse reactions.

In a 2008 presentation to the Army Office of the Surgeon General, an Army doctor reported that during the 2008 fiscal year, “at least 5% of Army soldiers were prescribed mefloquine” despite having a known contraindication, a problem that persisted as late as 2013.

The military’s mefloquine mistakes may have extended beyond long-term, systemic failure to ensure that its use of the drug was in line with medical and legal standards. There are suggestions that military officials downplayed problems with the medication.

Media reports have chronicled some of these incidents. Two journalists, Mark Benjamin and Dan Olmsted, were responsible for the most important reporting on mefloquine. From 2002 to 2005, the duo wrote dozens of articles about the use of the drug in the military, winning the National Mental Health Association’s Best Wire Service Reporting award for United Press International. Among their most notable stories were an early investigation into the connection between mefloquine and suicide and an exposé implicating mefloquine in all six suicides of Special Forces soldiers between September 2001 and September 2004. (Pogány knew one of these men; Chief Warrant Officer William Howell was a member of his Special Forces detachment in Iraq). Suicides among these elite troops are unusual. They include some of the world’s most highly trained warriors and undergo extensive psychological screening as part of their training.

One of the suspicious incidents that the two reporters wrote about concerns suicides among soldiers stationed in Iraq. In February, 2004, the Army’s top medical official gave Congress mistaken information about mefloquine’s possible role in the recent suicides of Army personnel stationed in the country. Testifying before a House Armed Services subcommittee, Army Surgeon General James B. Peake dismissed the drug as the cause of the spike. Of the 24 soldier suicides in Iraq in 2003, Peake said, mefloquine could have been involved in four at most. Seven months after the subcommittee hearing, the Army upped to eight the number of dead soldiers who had belonged to units in which mefloquine was the primary antimalarial and reported that three other soldiers were in units where both mefloquine and another drug were in use. Even before Peake’s testimony, the Army had begun to curtail use of mefloquine in Iraq. Concurrently, the 2004 suicide rate among soldiers in the country plunged to less than half of what it had been in 2003. The Army credited its suicide prevention initiatives and denied any connection to lessened use of the drug.

Nevin and other experts have pointed to a strong connection between mefloquine and suicidal thoughts—and occasionally even actual suicides. Roche, which still sells the drug in many countries, resisted this connection for years. The company argued—in spite of growing evidence—that there was no clear causal link between mefloquine and suicide. In 2013, however, an Irish TV network began investigating the drug’s role in suicides in the Irish military, and recruited Nevin to analyze their data on the subject. Nevin found a 300 percent to 500 percent increase in suicide risk among soldiers prescribed mefloquine, as compared to their compatriots who did not take the drug. Soon after the report aired, Roche’s Irish division updated the country’s product information to read, “Cases of suicide, suicidal thoughts and self-endangering behaviour such as attempted suicide have been reported.” The company also removed a phrase included in earlier versions: “no relationship to drug administration has been confirmed.”

At the time of writing, Roche had not responded to my repeated requests for comment, but in the past, the company has told reporters that there is no demonstrated link between mefloquine and suicide, and that the drug is generally safe and well-tolerated among users.

In 2009, the Pentagon made a major change in its mefloquine policy and acknowledged the drug’s possible neurological effects. In a December memo, Ellen P. Embrey, the acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Force Health and Preparedness, acknowledged that “mefloquine use has been associated with severe neurobehavioral disorders, and when used for prophylaxis, mefloquine may cause psychiatric symptoms.” She noted its effectiveness in preventing malaria, and that it is safe for most users. However, she downgraded mefloquine to the DoD’s third choice for malaria prevention, adding that it should be prescribed “very cautiously and with adequate clinical follow-up,” and only when the safer drugs doxycycline and Malarone could not be used.

Embrey’s mandate did not immediately solve the military’s mefloquine problems: CBS reported in 2013 that military doctors wrote 18,000 mefloquine prescriptions during the four years following her memo. One in 15 of these went to soldiers whose mental health problems should have barred them from being given the drug. More directives soon followed. In 2013, the FDA added its most serious “black box” warning to the drug label, acknowledging mefloquine’s “risk of serious psychiatric and nerve side effects” and warning that some side effects “can last for months to years after the drug is stopped or can be permanent.” Soon after, Army Special Operations banned the drug’s use among the elite soldiers under its command. At this point, military use of the drug is rare.

But chronic effects of mefloquine persist among some service members who took the medication. This may prove to be a serious, common issue in veterans’ health. At present, however, critical shortcomings in the understanding of the drug and its consequences make it hard to assess the scope of the problem. As Nevin told Congress in 2012, mefloquine “may become the Agent Orange of our generation.”

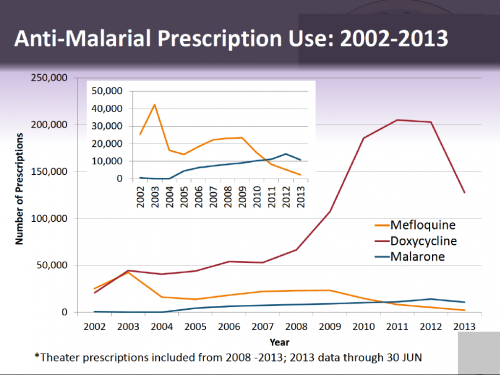

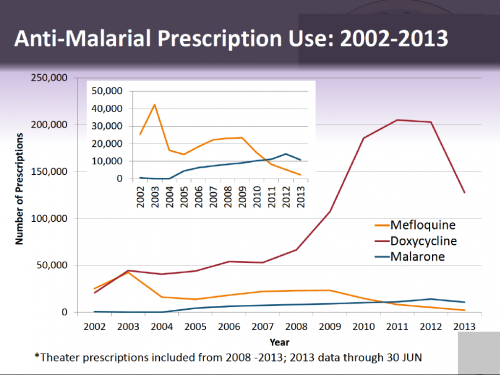

In August of 2002, Olmsted and Benjamin quoted an Army spokesman as saying, “There are hundreds of thousands of soldiers who have taken mefloquine.” A recently released Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center internal presentation contains similar figures. The document puts the total number of mefloquine prescriptions issued from 2002 to 2013 at just over a quarter million. Some service members would have received multiple prescriptions, so this does not suggest that 250,000 soldiers took the drug during the period. And although the presentation includes in-theater prescriptions for 2008 onward, the real number is probably higher, as recordkeeping problems persisted during those years.

A graph showing military antimalarial prescription numbers. The graphic is a slide from a recently released, heavily redacted Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center presentation on adverse events following mefloquine exposure

We also lack good information about how often soldiers who took the drug experienced serious problems as a result. In speaking with veterans, I was shocked at how commonly they reported serious problems related to mefloquine among soldiers in their units. Of the 12 men in Pogány’s Special Forces detachment, at least two—Pogány himself and Bill Howell, who killed himself—seem to have suffered extreme reactions. I spoke with two Navy veterans, Vincent Lopez and his commanding officer, Bill Manofsky, who served together during the Iraq War. Both men receive VA compensation for mefloquine-related brain damage, and at least two others in their seven-person unit suffer from similar maladies.

These numbers seem to indicate a rate of serious adverse reactions higher than any study has shown. Anecdotal reports are not the same as rigorous research, of course. These units could have been statistical anomalies, but Nevin doesn’t think so. He told me there is nothing unusual in the rate of side effects in the two men’s unit except that “In Manofsky’s case, he ensured that his men and women were taken care of and properly diagnosed. In other units, these injuries were almost certainly overlooked or misdiagnosed,” he said. “As I may have said, this is a hidden epidemic.”

We also know relatively little about mefloquine toxicity. Despite the efforts of Nevin, Ritchie, and other scientists, the problem has never been studied on a significant scale, nor has much funding been dedicated to such research. In fact, too little is known even to assign a name to the condition: “Mefloquine intoxication” describes a phenomenon that causes various known symptoms, but it is not a diagnosis. Another problem, largely peculiar to military populations, has recently entered the discussion: the potential for mefloquine’s effects to confound diagnoses of other health problems.

Many symptoms of psychiatric conditions common among soldiers—especially PTSD, but also traumatic brain injury, acute stress syndrome, and anxiety disorders—overlap with those of mefloquine toxicity. The diagnostic criteria for PTSD overlap, too. These include intrusive memories, nightmares and other sleep issues, flashbacks, irritability, memory problems, hypervigilance, acute distress, and impaired functioning. Doctors who are not aware of this symmetry—and who may be in the habit of making PTSD diagnoses in the absence of another obvious cause—might fail to detect mefloquine-related problems in addition to PTSD, or assign a diagnosis of PTSD to someone whose symptoms were caused entirely by mefloquine.

In one case that Nevin reported, a soldier who was given prescriptions for mefloquine and an antidepressant—despite DoD policies against this combination—was diagnosed five weeks later with anxiety and organic brain disease consistent with damage caused by mefloquine toxicity. Within another five weeks, the soldier had attempted suicide and been diagnosed with depression and PTSD. As Nevin wrote in a textbook chapter on the subject, “Although the actual number of those potentially receiving a PTSD diagnosis under similar circumstances is far from certain, the possibility that at least some diagnosed cases may represent missed diagnoses of mefloquine intoxication seems apparent.”

Nevin says he is personally familiar with more than a dozen cases in which the drug’s chronic effects caused or contributed to symptoms. (Because he is “not formally following this cohort under an approved research protocol,” Nevin told me, he hesitates to provide an exact number.)

“I feel comfortable estimating that among our current veterans exposed to mefloquine, single digit percentages of cases diagnosed as TBI, PTSD, and related disorders reflect primarily the lasting effects of mefloquine toxicity,” Nevin told me in an email. These are cases of veterans who “would be mostly healthy” if not for their use of the drug, he wrote.

Such clear-cut cases are the minority, however. More often, veterans have both PTSD and chronic symptoms of mefloquine toxicity. In these cases, it is hard to determine the genesis of their symptoms.

Given the number of soldiers who took mefloquine, the number of those who suffer from the drug’s effects but blame their symptoms entirely on a diagnosis like PTSD may be substantial.

Another complication is that most veterans aren’t aware that mefloquine can cause such symptoms. And because the drug was so often doled out without any information, and without adequate recordkeeping, it is common for them not even to know whether they took mefloquine. The absence of these records presents a serious problem: It has made it difficult for some veterans even to prove that they took the drug, let alone that it caused them ongoing health problems worthy of VA compensation. They may never receive treatment or compensation for their injuries.

There are signs that the Defense Department is aware of the potential problem of mefloquine confounding other diagnoses. The Department of Veterans Affairs has had at least an inkling of it since 2004, when a VA letter of information acknowledged that a “number of anecdotal and media reports have suggested that mefloquine has caused more serious side effects, including . . . symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder.” The Centers for Disease Control’s Yellow Book on travelers’ health, a Bible for healthcare providers, contains a “Special Considerations for US Military Deployments” section. In the 2012 version, a military doctor included new information noting that mefloquine’s effects could potentially confound the diagnosis of PTSD and TBI. That portion has been removed from this year’s Yellow Book. The Pentagon has also studied the problem to some extent. The graph of mefloquine prescription rates shown above came from a summary of recent military research on adverse reactions to mefloquine. The study has not been published, and all the research results were redacted from the document.

The drug’s consequences may well become more apparent in the years and decades to come, as knowledge grows among doctors and researchers, and as more veterans question whether mefloquine contributed to their own lasting injuries. If the future bears out Nevin’s suspicions, the military will face the considerable tasks of identifying overlooked cases of mefloquine toxicity, treating them, and educating veterans about them.

In the meantime, the military is testing an inauspicious new antimalarial in partnership with the drug company GlaxoSmithKline. Now called tafenoquine, the drug was originally designated WR 238,605—a product of the same Walter Reed program that yielded mefloquine. Like mefloquine and quinacrine, it is a quinoline derivative and shows early signs of toxicity and bizarre psychiatric effects.

A sign posted at the 363rd Station Hospital in Papua New Guinea during World War II admonishes soldiers to take their antimalarials

The first hint of the crisis that would come to define Capt. Remington Nevin’s career appeared one morning early in January 2007, in the form of an Army medic holding a black plastic garbage bag in his outstretched hands.

The man stood at the exit of Fort Bragg’s “Green Ramp” staging area, where Nevin and the rest of his unit in the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division had waited restively to board a jet that would fly them on the first leg of their journey to Afghanistan. As the soldiers filed out onto the runway, each was instructed to grab a packet of meds from the garbage bag. Nevin, the unit’s new preventive medicine doctor, did as he was told when his turn came. Without looking, he reached in and pulled out a cardboard package filled with dime-sized, chalky white tablets of an antimalarial called mefloquine hydrochloride, also known by its trade name, Lariam.

Given how unceremoniously the drug was distributed, the soldiers had no reason to suspect what medical regulators already knew: Mefloquine was a dangerous drug whose range of alarming neurological and psychiatric side effects might even include suicide. Even then, Nevin was aware that Department of Defense rules required the medication to be prescribed cautiously and with close attention to the recipient’s medical history. Yet the label on the package that Nevin plucked from the bag bore another soldier’s name.

Nevin was a recent transplant to the unit—to his chagrin, his insignias were still pinned to his camo fatigues rather than sewn on, the tell-tale sign of an “FNG.” Even had he wanted to, he probably could not have changed the unit’s antimalarial policies, which were decided before his arrival. In any case, he was not especially concerned. What Nevin knew about mefloquine at the time hewed to the Pentagon line, highlighted in a 2002 DoD memo: Rarely, the drug could cause problems and thus should not be given to people with mental health issues, but its effectiveness in malaria prevention outweighed its risks.

Soon, however, Nevin “recognized that even perfectly healthy people could be affected by the drug—that their behavior, personality, mood could be altered. It certainly upset patterns of sleep,” he told me.

While he was in Afghanistan, Nevin began to investigate the drug’s history and the scant available research about it. By the time he left the country, he was “quite convinced that this was a very dangerous drug—that we should not be using it at all.”

In the early 1960s, the emergence of drug-resistant forms of the protozoan that causes malaria rendered chloroquine—then the U.S. military’s mainstay antimalarial—ineffective in many parts of the world, including Vietnam. In response, the Army developed mefloquine and shepherded it through clinical testing.

It gradually became clear that mefloquine was a potent toxin that could cause debilitating and sometimes permanent side effects, but military health care providers continued to issue it to service members en masse, most notably in Iraq and Afghanistan. Military officials repeatedly ignored or downplayed evidence that the medication’s side effects are more common and more severe than they initially believed. And the military flouted its own rules for prescribing the drug, endangering thousands of soldiers and leaving some disabled. These problems persisted until 2013, when the DoD revised its policy and made mefloquine a drug of last resort.

Along with advocacy by Nevin and others, new research about the drug’s risks and side effects likely spurred the change. It may not have played a role in the DoD’s decision, but one recent finding has serious implications for veterans’ health: Symptoms of mefloquine toxicity can closely resemble those of combat-related mental health problems like post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury.

These similarities can lead doctors to make mistaken diagnoses of PTSD, or to miss the fact that a soldier is suffering from the effects of mefloquine toxicity in addition to PTSD. Nevin has documented more than a dozen such cases. By virtue of granting soldiers disability compensation, the VA has even given de facto acknowledgment in a few cases. Yet the number of veterans whose PTSD or similar diagnoses were either caused or exacerbated by taking mefloquine is unclear. Some important data simply do not exist—many soldiers’ mefloquine prescriptions were never recorded, for instance. The Pentagon has declined many requests to release other vital information, such as whether veterans who took the drug have higher rates of PTSD. In doing so, the military has made it nearly impossible to determine the scope of the veterans’ health problem posed by mefloquine-related brain damage, which Nevin believes is “the third signature injury of modern war.”

For armies in malarious areas, drugs that prevent and treat malaria are almost as important as fuel, food, or bullets. Without them, soldiers die.

“The history of malaria in war might almost be taken to be the history of war itself.”

Since antiquity, malaria has marched with armies and killed soldiers, often shaping history in the process. Alexander the Great may have succumbed to it. Historians speculate that Attila the Hun’s fear of exposing his armies to a city rife with malaria stopped him from sacking Rome in A.D. 492. George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses S. Grant all suffered from the malady. It has been such a constant feature of human conflict that a British Royal Army doctor once wrote—with only slight hyperbole—that “the history of malaria in war might almost be taken to be the history of war itself.”

When the U.S. Army’s Medical Department was formed in 1775, scientists had little understanding of the germ theory of disease, much less the specific causes of malaria—then referred to by names like “intermittent fever,” “marsh fever,” and “ague.” And although the characteristic progression of violent chills, scalding fevers, vomiting, headaches, profuse sweating, delirium, and sometimes even death was all too familiar, little was known about how to prevent it. However inadequate, the prevailing wisdom in 18th-century preventive medicine was to urge troops to avoid miasmic vapors found in swamps and bogs, particularly during spring and late summer.

In 1820, two Parisian chemists isolated quinine, the first effective antimalarial. Sixty years later, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, a French army surgeon, discovered Plasmodium protozoa in a patient’s blood and identified them as the cause of malaria. In 1897, a British doctor named Ronald Ross demonstrated that mosquitoes transmitted Laveran’s parasite. Knowing malaria’s cause and manner of transmission gave scientists the information they needed to find effective new ways to fight the disease. The epochal significance of Ross’ breakthrough moved him to verse:

With tears and toiling breath,

I find thy cunning seeds,

O million-murdering Death.

I know this little thing

A myriad men will save.

By the early 20th century, the United States, and the Army in particular, had moved into the world lead in the study and control of malaria, forced, in part, by the disastrous spread of malarial infection among Panama Canal workers. The Army transferred Col. William Crawford Gorgas, a physician, to the isthmus. Gorgas had done pioneering work to curb yellow fever in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. When Gorgas began his work in 1906, some 26,000 people were employed on the canal project. That year, malaria sent about 21,000 of them to the hospital—more than 80 percent of the workforce. Gorgas had the swamps drained to control mosquito populations and instituted a mandatory twice-daily ration of 150 milligrams of quinine per worker. By 1912, he had reduced the hospitalization rate to 1.6 percent—a feat so staggering that a contemporary referred to it as “a chapter in human achievement for which it would be hard to find a parallel.”

Even with these breakthroughs in the understanding and management of malaria, the disease still posed major problems in later American operations abroad.

World War II was a particular case in point. From the Philippines to Sicily, malaria ravaged U.S. troops. In the South Pacific, the disease caused eight times more casualties (a term that describes both deaths and injuries) than did combat.

A 1943 Army malaria-prevention illustration created by Theodor Geisel, later known as Dr. Seuss

In desperation, the United States embarked on a search for antimalarial drugs, eventually settling on quinacrine, a compound that German chemists had invented in the early 1930s. Quinacrine (brand name Atabrine) was moderately effective and helped the Allies control malaria rates. Ultimately, however, problematic side effects forced the Army to develop alternatives. Soldiers who took quinacrine experienced headaches, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, nightmares, and even psychosis. The drug—which was originally developed as an industrial dye—also had a tendency to turn their skin and eyes yellow.

As evidence emerged during the war demonstrating how common the negative effects of the drug could be, the military’s reaction foreshadowed how, decades later, it would respond to mefloquine. The military restricted information about the drug’s side effects for the duration of the war. A 1944 Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery newsletter—described by Nevin as a publication “containing information and signed official recommendations which should be considered doctrinal”—said only that “psychological disturbances occasionally appear” in users, and that the quinacrine could cause “mild excitement” and, rarely, “acute maniacal psychoses.”

As the war ended and American GIs left malarious areas, the Army’s drug discovery program continued. By 1947, it produced an alternative called chloroquine. Although it was chemically related to quinine and quinacrine—all three belong to the family of quinoline derivatives that also includes mefloquine—it was thought to be safer and more effective than the other two.

For the next decade or so, chloroquine worked well in protecting American troops stationed abroad, until a deadly form of the malaria parasite developed resistance to the drug. By 1961, it was infecting American soldiers stationed in Vietnam and had spread across Southeast Asia. Again, the military founds its main weapon against malaria useless; again, it initiated a frantic drug development push.

In 1961, scientists at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research embarked on the costliest drug search ever mounted to date, a titanic undertaking in which Army researchers collaborated with a host of governmental agencies, academic organizations, and companies, including 175 external contractors. By 1968, they were screening up to 1,000 chemical compounds every month, to little effect. None of the hundreds of thousands of drugs they tested had proven safe and effective. Meanwhile, 9,000 miles away, American soldiers remained vulnerable.

The program bore fruit a year later. The researchers found a compound—then known only by a Walter Reed experimental number, WR 142490—that worked against the parasite and was not unduly toxic. The drug, later named mefloquine, seemed like a godsend.

At some point in the 1970s—the details are obscure, having never been made public—the DoD started collaborating with the Swiss pharmaceutical giant Hoffman-La Roche. The two entities soon began the testing needed to bring the drug to market.

Initial published reports were glowing. Early testing revealed little in the way of serious adverse reactions to the drug.

Although the apparent absence of toxic side effects was seen as encouraging, hindsight suggests this was not evidence of drug safety, but rather of insufficient research. Mefloquine was tested less extensively than most pharmaceuticals. Dr. Ashley Croft, a former British Army physician and a prominent critic of mefloquine’s use has noted the drug’s clinical trials were rushed, and that researchers ignored danger signs.

Nevin knows this story well. He has been as central to mefloquine’s recent history as anyone alive. Had he been born three decades earlier, he might have been part of the cohort of Army doctors who developed and tested the drug. But instead, Nevin was born in Canada in 1974, the son of an American draft-dodger who fled North to avoid the very war that gave rise to mefloquine; and he has has done most of his mefloquine-related work as a civilian. Nevin ended his 14-year career with the Army in 2012 and enrolled in public health doctoral program at Johns Hopkins University. He has made a relentless, almost obsessive study of the drug and its effects ever since, but he didn’t plan it that way.

Nevin’s future in the Army had been promising. He was a top preventive medicine student in medical school—he won an award for it—then a top preventive medicine resident. He was given a distinguished first assignment. People told him he’d be Army surgeon general one day, although he modestly says he thinks they were exaggerating. “I had a nice corner office. Life was very good. I hired half a dozen staff to work for me,” Nevin told me.

By the end of his deployment to Afghanistan, that had all changed. While he was there, he got a look at how military health care works in practice. It was much more troubling than the view from his corner office just outside the Washington, D.C. Beltway. A number of things he saw in Afghanistan troubled him, the Army’s mefloquine practices important among them. He spoke out. “By the time I returned home from Afghanistan, of course, you know my career prospects had taken a turn for the worse. I realized I’m probably not going to be serving a career in the military,” Nevin told me.

He also began to see mefloquine as a serious, unacknowledged threat to soldiers’ health, one that he felt uniquely positioned to confront. “You are just in the wrong place at the wrong time—or the right place at the right time,” he said, “where an issue lands in your lap and you realize there is really no one else that can address this as well as you can at the moment. And it becomes your responsibility.”

A picture of Nevin that appears on his website

Nevin has published dozens of scientific articles about issues related to mefloquine, research that has made him the most prominent American scientist in the field. He has also chronicled the drug’s effects on dozens of people, many of them veterans, and is often retained as an expert witness in trials involving mefloquine. He has also appeared before Congress and the British House of Commons, urging lawmakers to restrict the drug’s use.

Nevin has become something of a niche media darling. A quote from him is almost perfunctory in news stories about mefloquine. Quite apart from his articulateness and professional distinction, he makes an impression with his booming voice, salt-and-pepper beard, and distinctive manner of dress—several open buttons often leaving a triangle of chest hair on roguish display.

Nevin has doggedly investigated the military’s mistakes regarding mefloquine policy and development. In his account, lack of adequate clinical testing was mefloquine’s birth defect, the first of many mistakes leading to the considerable harm it has caused.

The rush through Walter Reed and Roche drug trials meant no normal preclinical animal testing took place. This was an oversight, Nevin said: Scientists knew that other members of mefloquine’s chemical family had toxic effects on the brain, so it would have been logical to check whether mefloquine did, too. Instead, researchers moved quickly to Phase I, the first of three stages of human testing that medicines undergo in the hope of Food and Drug Administration approval.