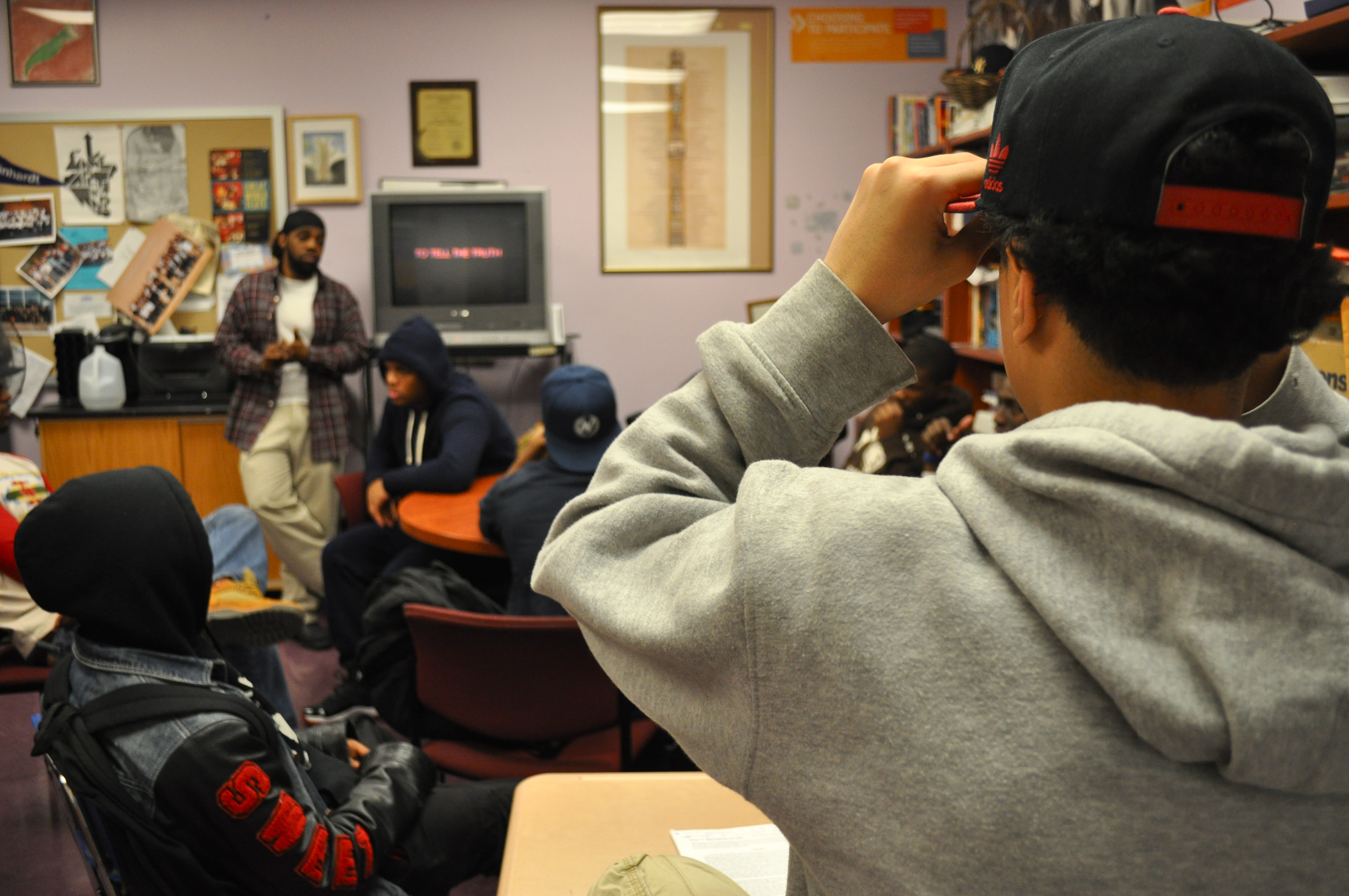

School’s out on a Wednesday and Courtney Robinson’s office is full. He’s the dean of students at Facing History High School on the outskirts of Hell’s Kitchen, but no, these kids aren’t here for detention. High school boys shuffle in and out, dressed the way teenagers dress, some in sweatshirts with hoods pulled floppily over their heads; others in navy polos embroidered with a special insignia: tiny hands clasped around a globe. They chat, complain and tease one another until precisely 1:35 p.m., when Robinson ushers out the hangers-on while those in the polos plop into whatever seat they can for a meeting of the Human United Strength Organization, or HUSO. The topics range from rap music to Malcolm X but the subtext always centers on the meaning of masculinity. “All right, guys,” Robinson begins. “Let’s check in.”

A senior named Devante Moore usually talks about basketball. He speaks faster and faster as he becomes angrier and angrier. Apparently, this year’s coach isn’t his favorite. John Susana, a freshman, mentions in a mumble that his grades are good, and his small audience claps for his success.

Room 227 is a safe place. One boy shares that his favorite Christmas gift was a hug from his mom. It’s a supportive place. Robinson listens intently to the students’ problems and responds with short, succinct suggestions for non-violent solutions. It’s a male place, a haven for these high schoolers to talk about the things they ordinarily would find difficult to air in public. They call it the HUSO Mentoring Group, or HMG, an after-school offshoot of Robinson’s self-established umbrella organization. He hopes to see his group replicated in more city schools, even though there are already a number of such male-oriented clubs operating under other leadership, both in New York and across the country. The purpose of these programs is to give boys the chance to rethink what maleness is really all about, what it means to be a man, and how to change the way men treat women and each other. Organizers say the construct works once the young men decide to participate. Getting them in the door and then finding the money to keep the doors open are often the two biggest challenges.

Jermaine Atkins is a soft-spoken senior who regularly attends the group meeting in Robinson’s office. He listens intently. He rarely voices his opinion during their sessions, but when he does it’s with a weakly raised hand and a whispered thought. Atkins joined Robinson’s group after sensing a difference in its members—he noticed how they moved, how they acted more maturely, how they worked to better themselves.

Courtney Robinson, far left, listens to his students one Wednesday afternoon during a HUSO meeting in Room 227.

Moore, the one who always brings up basketball, found his way to the group through the recommendation of a friend, the most common entry route to Room 227. The invitations come through cousins, brothers, friends of friends—forming what they call a fraternity, a gang of a different sort. For others, friendly recommendations fail to convince them of the benefits of such a brotherhood. Moore calls those students weak-minded. “This is for people who got strong minds, who are willing to step up to the plate and really become a young man.” Atkins said the group has become his source of inspiration. “It reminds me that I don’t wanna just survive.” The group has helped him see more possibilities for himself after graduation. “This group inspires you to be better than everybody else,” he said, “to be a better person.”

When Robinson got the idea to start his organization, he did not know it would make him part of a much larger movement, one that has been working for the past 40 years to engage men in the prevention of violence against women. The first such experiments emerged during the second wave of the feminist movement, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when male activists realized the positive impact of their support in the battle for women’s rights.

While the media was then equating the women’s movement with bra-burning protesters of the Miss America pageant, feminist scholars were busy separating sex from gender, defining the latter as a construct, a creation of society, rather than as an immutable, inborn reality. Male activists responded in two different ways. Some joined the extremist men’s rights movement and embraced anti-feminist beliefs that gave the lie to the notion that women are oppressed. Others, known as “anti-sexists,” supported the rights of their female partners, a crusade that at first was little more than a weak and scattered army without provisions or direction. But with “The First National Conference on Men and Masculinity” in 1975, organized by men at the University of Tennessee, structure soon followed.

These annual conferences continued for the next five years, during which a new pro-women, pro-gay identity evolved. In 1983, the group became the National Organization for Changing Men, and seven years later, the National Organization for Men Against Sexism.

As gender studies gained credibility throughout the 1970s and ‘80s as an academic discipline, some scholars of feminist theory began to develop a new focus known as masculinity studies.

Dr. Ronald Levant played a significant role in the development of masculinity ideology, something he defines as “an individual’s internalization of cultural belief systems and attitudes toward masculinity and men’s roles.” In 1992, he and his colleagues created the Male Role Norms Inventory, which measures adherence to seven norms of the Western masculinity ideology. These include suppressed emotional responses, avoidance of traditionally feminine behavior and appearance of aggressiveness as a desired value.

Since its first publication, a number of psychologists have used Dr. Levant’s inventory in their own studies to further examine gender ideologies in specific contexts, such as in comparisons involving sexual orientation or race. For instance, in one study, gay males generally exhibited less traditional masculine behavior when compared to heterosexual white college men. In another, Russian and Chinese college students endorsed traditional masculine behavior more than their American counterparts did. Psychologists also have found that men who embrace more traditional masculine ideology are reluctant to discuss condom use with their partners, have less satisfactory relationships with their partners, and harbor attitudes that often lead to the sexual harassment of women.

As Dr. Levant told Psychotherapy, “The long and short of it is that traditional masculinity is hazardous to men’s health.”

So instead of putting energy and resources into warning women about dark streets and risqué clothing, those who advocate for female victims of sexual abuse, such as Lina Juarbe Botella, realized that their primary focus should be on changing the behavior of abusive men. “Women cannot be safe,” Botella said, “until men know how to behave.”

Tony Porter and Ted Bunch were two such men who founded A Call to Men in 2002 after being heavily involved in social justice activism for several years. The national organization educates men and boys on healthy forms of masculinity in an effort to prevent sexual violence. Botella joined Porter and Bunch as the organization’s training director. The two founders, she said, “meet men where they’re at physically and emotionally,” to encourage them to act as positive role models for their sons, brothers and friends. But the two men also acknowledge the debt they owe to the women like Botella’s predecessors, who came before them as workers for the same cause.

Botella admitted that she originally had difficulty accepting men as partners in the field of female advocacy. But her current focus on prevention has taught her how to embrace their presence. “I can’t take any credit for it, but Tony and Ted had a lot of wisdom on how to do so,” she said. “How to be with men, all types of men, from the barbershop to the boardroom. This is really a men’s issue,” she added. “We need to engage men so that we can ensure a collective liberation.”

A Call to Men’s mission goes beyond working with men of violence to include community leaders, fathers, brothers and uncles. “If I have my arms stretched out open to symbolize all the men in our society, a small percentage of them are abusers,” Botella explained. “We particularly focus on men who are on the other side, who are on the line, who might stop those jokes or create a society without confrontation.” Her approach aims to encourage men to change the conversations they are having about masculinity and about women. For example, when someone excitedly shares a sexist joke by the office watercooler, A Call to Men wants male bystanders to shut it down before he gets to the punchline.

Jamie Utt, who describes himself as a diversity and inclusion consultant, travels around the United States to speak at schools about positive sexuality, bullying prevention and student leadership. Yet when he thinks he cannot offer what the prospective audience wants in terms of programming, such as topics involving race and sexuality, he prefers to turn down the offer and suggest a substitute speaker. On occasions when he presents with a black female colleague, he gives up 31 cents out of every dollar he is offered as a statement about the payment women of color receive when compared to white men.

“I think that we can motivate people to act,” he said over Skype from his home in Minnesota, “but it so often comes from a place of charity, you know? We’re trying to motivate men to change masculinity for women, but then it’s this paternalistic sort of charity versus trying to get men to change masculinity because of their personal investment in it and their relationships.” Utt knows well there are no gold medals or blue ribbons for advocacy work. He said he just wants men to realize the importance of engaging with their partners and responding to their needs.

Carlos Andrés Gómez shares a similar message. He came to realize the negative consequences of most traditionally masculine behavior through a series of shallow relationships, fights with his father, and losses both personal and material. Already an HBO Def Jam poet, actor, and public speaker, he added author to that list in 2012 with his book, Man Up: Reimagining Modern Manhood. In it, he writes about renouncing his identity as a guy known for liking to pick a fight and then taking up another as a poet; “a journey to becoming a man, a different kind of man, a man who lives and moves and acts outside of the predetermined boundaries of masculinity,” as he writes in the book.

Before sitting down with him, I felt like I already knew mostly everything about Gómez. His book details his rocky relationship with his father and gives a rather detailed timeline of his romantic life and sexual exploits. He laughed when I told him that I had difficulty coming up with questions for him since he had revealed so much in his text. His blue-green eyes crinkled into half moons and his smile widened as he threw back his head, and quickly evident was the source of his appeal to audiences around the country, from those who pay to hear him speak to teenage boys serving time on Riker's Island.

“I mean, so much about toxic masculinity is all about hoping the world doesn’t see how hard you’re trying,” he said. “Whether it’s a guy rocking 28-inch rims, or a guy outside of a party with his shirt ripped off, beating his chest, yelling at the top of his lungs, or a guy bragging how big his dick is—it’s all about this performance. It’s all a performance to hope the world doesn’t see that there’s a little boy in there who’s shaking and scared and hurting.”

The topic of privilege repeatedly came up during our discussion—the privilege society confers on men, the privilege society ascribes to being white or sometimes even just appearing to be white, as in the case of the blue-green-eyed Gómez. He prides himself on being able to walk into a room and completely disorient those he encounters. Gómez is well-built; his large shoulders and arms signal days at the gym. His light skin allows inadvertent passing. He “plays up” his masculinity when he walks into a school, “very much by design,” he assures me, but when he delivers emotional poems on stage, he leaves the tears on his cheeks. He likes to challenge and confuse.

When people watch a “masculine-oriented” man break all the rules they’ve been taught about gender, they don’t know what to do. Gómez remembers the numerous times he has spoken at high schools where boys continuously ask him if he’s gay—he’s not—because he recited a poem called “Handstitch” about holding his male friend’s hand. “I said, ‘Number one, does it make a difference to you?’” No, they say, they’re just curious. So he replies, “None of your damn business.”

And that, he says, always makes them go crazy because they don’t know what box to put him in. He’s not in the white or Latino box. He’s not in the straight male box—but shouldn’t he be? Not if he cries and talks about intimacy and vulnerability and sensitivity. So much in the way that Robinson tries to break down masculinity in Room 227 on Wednesday afternoons, Gómez does so when he performs in front of an audience. The two men may have different approaches, but they work toward the same goal in safe, private spaces.

Mentoring for Robinson started at home in Harlem, when he was just a boy. His mother kept the front door open for any child in need, and those who came also looked informally to Robinson for advice. He calls his mother the strongest person in his life.

So when the former principal of Facing History, Robinson’s first boss, told him that young men at the school were “falling through the cracks,” the dean of students saw a chance to continue mentoring in a more formal manner. He quietly began planning a program that would pick these boys back up. With thick arms coated with tattoos and dark dreaded hair secured with a do-rag and pulled back into a braided bun, he now tells his club members that they’re walking examples of respectful male students, ones who choose conversation over clenched fists.

One afternoon, a 17-year-old member of the group named Ronnie told the rest of the boys about “this one Spanish kid” who always frustrates him. After 10 minutes of complaining about this fellow classmate with more than a few hints of a possible physical fight, Robinson stepped in.

“It makes you upset because you see potential in him that’s being wasted,” he told the boy, who then nodded his head in agreement and rubbed his hand over his cropped hair. “You know he’d be a good addition to the group and it just makes you mad that he won’t join.” Ronnie responded quietly, “Yeah, yeah, you’re right.”

For men doing advocacy work, both the motivation and inspiration that leads them to engage with this work varies widely. Even though the issue of sexual violence floods our news feeds, it often takes knowing a victim for men to realize the urgency of the issue. Before Jamie Utt became a well-known public speaker, he was handing out advice as a student at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana. “For whatever reason, I found that a number of different friends had come to me seeking support after sexual assaults,” he said. “And I felt like I just didn’t know how to help.”

And although the word “selfless” came to mind when speaking with Utt, he said otherwise. He called his interest selfish in the sense that it satisfied his own need to be in a position to serve the people he cared about and to help the survivors of sexual abuse in his own life toward recovery.

In Utt’s student days, Earlham offered a nationally recognized survivor’s advocacy program. Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network, one of the country’s largest anti-abuse organizations, called it one of the best programs in the country. It’s not in existence anymore because of “frustrating funding cuts,” Utt said, but when he was a student, it acted as a model for other such efforts around the nation. Participants met three times a week for 90 minutes, then attended practicum once a week to practice advocacy and act out possible situations that might arise when dealing with victims of sexual abuse.

Ryan Eton, a current student at the Harvard Medical School, was keenly aware of the impact of acts of sexual violence but was just as aware of the fact that men seemed never to talk about it. While in pre-med at Columbia University, he noticed an advertisement taped on a bus shelter for the Crime Victims Treatment Center.

The poster asked, “Do you want to be an advocate for rape and sexual violence in the ER?” His schedule didn’t allow him to train to be a volunteer at the center, which required 40 hours over two weekends—the average in most states. But he kept it in mind. “There was some motivation on the other end,” he added. “A close friend of mine had been a survivor of rape and a family member had been a survivor of domestic assault, so I was sensitive to the issues.” He trained the following fall.

Before he could start, Eton first had to make sure of one thing. “Do guys do this?” he asked Christopher Bromson, the assistant director. It’s a question Bromson hears often, to which he always answers yes. When Bromson himself first trained to be an advocate, there were only two other men in his group. By the time Eton trained three years later, there were five or six. This past year, there were 10. And of 212 people the center has trained over the years, 40 or so are men. For victims sent to the emergency room, just having a trained volunteer present can be important, regardless of the volunteer’s gender, Bromson said. He added that only once that he can remember in the four and a half years that he has been coordinating volunteers has a victim turned a male volunteer away.

Eton’s volunteer training has made him more vocal about the issue of sexual violence. “I never heard a peep of rape or domestic violence before this training,” he said. “Guys don’t talk about this.” But girls do, he said. They make sure not to walk alone after 11 p.m., and by warning each other of such risks, they acknowledge the larger problem of assault. Young men usually don’t worry about the long walk home, nor the response their clothing might provoke. Eton believes that the volunteering process will prompt more of these discussions among men; even with other men who work at the hospitals when the volunteers come on duty, from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m., when social workers are not available. Bromson said an average of three sexual assault victims enter ER doors in search of help every two days. The center’s volunteers serve some 1,200 victims each year at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital Center alone.

Each night in the ER is different. Some shifts require the whole night at the hospital; other times volunteers wait at home for a call that may or may not come. Tom Barber’s phone didn’t ring the first few nights he was on call, and when it finally did, it was chaos. Both a man and a woman were under arrest, six policemen were standing outside the door, and the mother’s child was bouncing off the walls. “I ended up playing trucks with the one-year-old,” Barber said with a chuckle. “The best thing I could do was give the mom a break.”

Barber is a novelist. He dreams up fictional stories for a living. So finding himself in an emergency room comforting victims of sexual abuse was not on his bucket list. In what he calls a previous life, he himself “fell victim” to the corporate world. After returning to school for a masters in fine arts, he knew he wanted to begin volunteering. He began searching for soup kitchens, but a woman in his class who was an advocate for victims of sexual abuse, sensed something different in him and suggested he train at the treatment center and become a volunteer.

“She happened to ask me at the exact right time,” he said. Barber has now been a volunteer for the past year and a half. He has a quiet demeanor. He takes long pauses before answering a question, and speaks thoughtfully. “CVTC does a great job of idiot-proofing this,” he said. “They have professionals that know what they’re doing,” Then, after a few seconds of silence, he added, “But it’s just about being a human being.”

Barber shared Eton’s concerns about being a male volunteer. “I was really nervous—as a matter of fact, I raised my hand in the training and asked, ‘Are they going to hate me because I’m a guy? Are they going to want to talk to me? Or are they going to be embarrassed? Do I need to worry about this?’”

Although his trainers reassured him, as they had reassured Eton, he said experience helped him over that fear. “To have one of the first people she sees afterward be a man who is kind, who is listening, can be powerful,” he said. “As part of the training, one of the things they tell you is to really help empower them to make the decision—they’re calling the shots, I’m just the facilitator of the decisions they make. I’m just there to help them get that power back.”

Teaching young men to value the models of maleness that men like Eton, Bromson, Barber, Utt, Gómez and Robinson are forging seems to be easier in a room full of strangers than it is in the locker room or at home. Gómez harkened to an expression— he couldn’t remember if it was Gandhi’s or Dr. King’s or someone else’s—“You know, it’s like anybody can confront an enemy, but it takes a true hero to confront a friend.”

He told the story of a recent trip to Alabama where the men he met represented what he calls “the front lines of the battle” to change the way men think about their masculinity. He said he prefers to speak at a place like this, where by the end of the session, a “pretty homophobic construction worker” was in tears talking about his son. To Gómez, watching that man’s transformation in the space of a one-hour meeting is “more revolutionary and more meaningful to me than 30 people who identify as activists” parroting what they already believe.

So even though Gómez doesn’t think we’re at the point where these conversations will be brought up casually at the dinner table, at least they’re beginning to happen somewhere.

And those venues have become virtual as well as physical. Online forums have a special appeal because they provide anonymity that gives guys the chance to be curious in private. Blogs like Masculinities 101, MasculinityU and Higher Unlearning have emerged as equivalents to Robinson’s classroom or Gómez’s stage. They encourage young men to debate, ask questions and learn about new definitions of masculinity. Twitter and Facebook generate numerous daily conversations in which postings fling around buzzwords such as “pro-feminism,” “healthy masculinity” and “positive sexuality.” On Twitter, search the hashtags #profeministmenshould and #EndSH to find an entire community of male advocates who tackle the issues of street harassment and sexual abuse with a keyboard.

Sacchi Patel is the co-founder of MasculinityU, a blog he founded in his free time from his job at Stanford University’s Office of Sexual Assault and Relationship Abuse Education and Response. The blog’s mission is to “free men up to define [masculinity] for themselves.” Patel was lucky enough to have a friend drag him into a men’s group during his undergraduate days at Syracuse University, and he continued to attend meetings as the “limitations of masculinity” became clearer and clearer. The more involved he became, the more his female friends confided in him about their experiences with sexual abuse and assault on campus. Patel became what he called a “safer guy.” Since not everyone has a friend to push him through the door, Patel co-founded the blog to give men and boys another platform for discussion.

Back at Facing History, leaning against a blue metal locker, staring straight across the hallway, Moore mentions the looming threat of gangs that often consumes the lives of his neighbors, friends and family. “There’s a lot of people in my neighborhood that I think could change their life around and stop doing gang violence and committing crimes with HUSO. You don’t have to be in a gang,” he says, “HMG’s our gang.”

One afternoon, Robinson asked his gang a simple question: Who is the realest person in your lives and why?

This was when one of the boys held up his mother as the realest—and sternest and toughest—person in his life and shared the story about the sweet gesture from her that became his favorite Christmas present ever. “You know, she finally gave me a hug,” he said slowly. The rest of the boys clapped. “It was a, ‘Come here, my son, I’m proud of you hug.” He smiled contentedly and nodded his head as the applause continued.

Many of the other boys pointed to their mothers in answer to Robinson’s question. They explained how these women continue to support their families, sometimes against daunting odds. Robinson was at work, breaking down the walls that prevent these young men from exposing their vulnerability. “In the inner city environments that they come from,” he explained, “it’s considered weak to expose your feelings to the public or to another party.” It’s the closed door of Room 227 that permits these boys to have these discussions. Just a few feet away in the hallway is another world, one where they push back their shoulders and throw out their chests a little bit more. Eventually they won’t need Robinson’s encouragement or the quiet click of a closing door before they can express their feelings.

Emiliano Diaz De Leon wasn’t aware of the male support group at his high school and was surprised when the school counselor referred him to the group after he acknowledged his need for help. At the time, he had confessed to being violent toward women he dated and said that there had been acts of abuse in his own family. Those early experiences led him to the job he now holds as the men’s engagement specialist at the Texas Association Against Sexual Assault. Although not everyone who comes to be passionate about this kind of advocacy starts because of an early intervention, many do, and he thinks the existence of such groups is a plus. “I think if we can get men to begin to do the work that early, that absolutely has an impact on their ability to continue doing the work as adult men.” Becoming a Man works with a similar idea in Chicago: to mentor high school-aged boys at risk of perpetrating or experiencing violent acts. President Obama has showed his support of the in-school program, and now has plans for a similar initiative called My Brother’s Keeper. Diaz De Leon became the first children’s male advocate at SafePlace, the women’s shelter that was his club’s sponsor, after having participated in his own high school group. Plenty of men had provided services to the organization—making repairs to the building and such—but none before Diaz De Leon had volunteered to work with the shelter’s clients.

“It was really the women, both the leadership at SafePlace and in the shelter, who took a risk, who both mentored me and challenged me and held me accountable,” he said. Once Diaz De Leon was let in, he said it was interesting mix of experiences. “For some of the women and children, they were very excited to see me, they were receptive of my presence. Some had a hard time with it. They had experienced a tremendous amount of violence from men who looked like me.” He felt the weight of being the first positive male role model to which most of the children had ever been exposed. “It really forces you, every day, to think about your behavior, language, the way that you walk, the way that you talk, the way that you are around the people in the shelter,” he said.

Gómez said that many men have false notions of what true power and strength really mean. Instead of investing in new ways of being, like Diaz De Leon learned to do, they just react badly. “And that’s what the word bitch is, or pussy, or faggot, or whatever it is,” Gómez explained. “It’s this pathetic, almost cartoonish, lashing out.”

Many psychologists and social workers believe that stories like Diaz De Leon’s can demonstrate to convicted sex offenders the possibility of recovering from abusive behavior patterns.

When sex offenders are released from prison, they are usually enrolled in a state-mandated treatment program. The groups for moderate to high risk offenders typically meet two or three times a week. In addition, each offender meets with a therapist once a month. This framework is based on relapse prevention, modeled after substance abuse treatment.

Dr. Bud Ballinger, a sex offense treatment provider, says that it’s not that this framework is a bad idea, “it just doesn’t fit for everybody.” The model attempts to determine the triggers of sexually abusive behavior, and works on eliminating them. The idea is pretty solid, says Dr. Ballinger, but it misses some elements. In his own treatment plan, he adds in cognitive behavior therapy, which examines the thoughts that allow perpetrators to justify their actions, and some skill-building that teaches abusers new coping mechanisms.

Treatment regimens, however, are not the only issue for ex-offenders. Re-entering society creates another set of challenges. An increasing number of psychologists assert that high recidivism rates can be attributed to the lack of support offered to released prisoners. The sex offender registry not only isolates them but points them out to their frightened and cautious neighbors. And although the registry has been effective as a deterrent, Dr. Ballinger says that around 95 percent of sexual offenses are committed by people engaged in these acts for the first time. “Even if it worked optimally,” he said, “it wouldn’t make that much of an impact because most of the people who are going to be sex offenders won’t be on that registry.”

Michele Frank said the difficulty with re-entry is obvious. “Nobody wants them in their community; nobody wants them in their shelter.” Frank was a private service provider for sexual offenders before she became a professor of social work at the New School. She noted a commonality she found in the released prisoners she has treated. “A good percentage of them come out of families of abuse and neglect. There’s abnormal child development, and we see that replicated in their families and we see them acting out in the world. We need to try to reach these individuals and try to understand what makes them tick and give them some power to understand themselves,” she said.

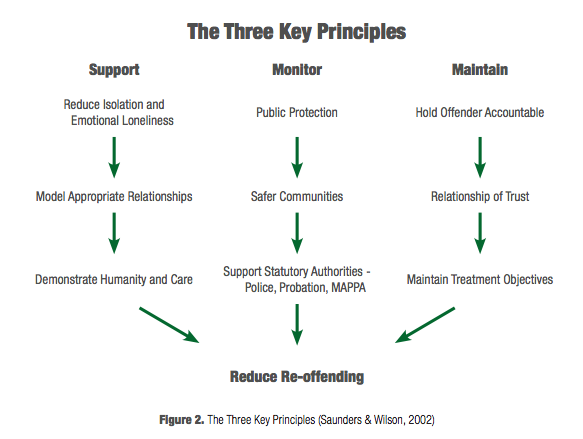

Even though she’s talking about a process that happens during treatment, some specialists believe that it should continue once offenders resume their lives outside. Circles of Support and Accountability, or CoSA, is a prisoner reentry program that hopes to reduce reoffending rates for sexual offenders after they’ve been released. First implemented in 1994 in Ontario, Canada, the program has since spread to the United Kingdom and United States.

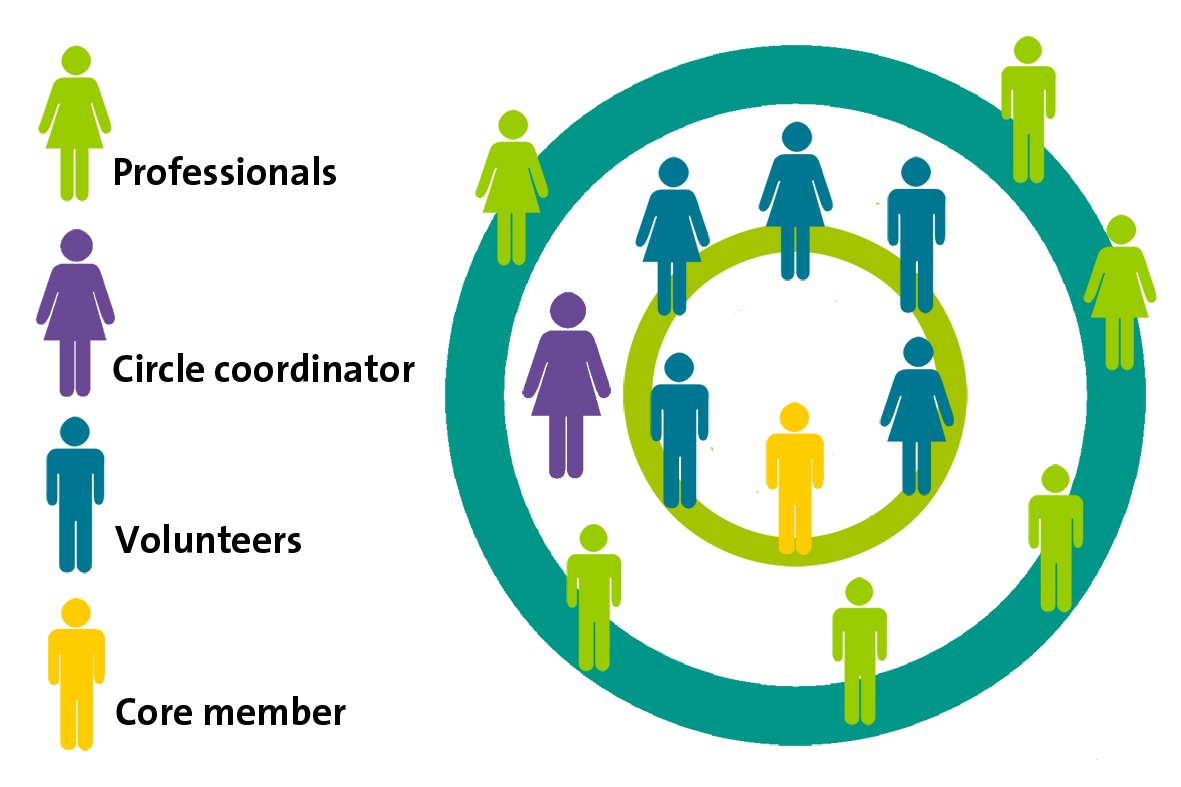

CoSA assembles four to six volunteers to form a support network for a released offender, referred to as a core member. The team meets regularly to work through the pushback offenders face when trying to settle into society. When the volunteers require professional help, they call on the “outer circle,” composed of psychologists, parole officers, social workers, and other professionals.

Graphic representation of CoSA model (adapted from Wilson & Picheca [2005], Netherlands Probation Service, 2012)

Dr. Robin Wilson is a clinical psychologist and researcher who has worked in the field of sexual offense treatment for the past 25 years. He was integral in the beginnings of CoSA in Canada and is now involved in getting it established in the United States. When asked what is most difficult about promoting this program in any region, he answered, “The infatuation with incarceration and marginalization of offenders.”

By that he meant the sensationalization of convicted criminals by the media, which tends to portray them as horrific monsters rather than as recovering human beings. It’s a problem that won’t disappear soon despite early studies that show the CoSA program has been able to reduce the sexual recidivism rate by 70 percent. Psychologists say they require more research to confirm the program’s effectiveness.

The cost benefits of the program however, are not at issue. In 2009, the Correctional Service of Canada found that every dollar spent on treatment for offenders resulted in a savings of five dollars in decreased reoffending. In a 2000 study, the U.S. Center for Sex Offender Management released figures showing that one year of intense treatment and supervision outside prison can cost between $5,000 and $15,000 per offender, depending on the type of treatment. With incarceration, the price goes up to around $22,000 per year, not counting treatment costs.

Dr. Wilson consistently finds that the program appeals to the released prisoners as well. “Once a jurisdiction gets familiar with the fact that CoSA exists, the offenders come out of the woodwork in droves,” he said. They grasp that such a program helps them protect their new status. However, not all offenders can handle the pressures of such a demanding program. “Getting out is not so hard,” he said. “Staying out is a much taller order.”

Dr. Wilson thinks the volunteer structure, as opposed to paid staff, is critical, because it provides “community buy-in” and a set of “ambassadors for truth in regard to sexual abuse and the people who perpetrate it.” Town hall meetings become classrooms and the circle begins to grow.

The voices of the boys in Room 227 rise in volume as they brainstorm. They shout over one another in excitement to share their fundraising ideas for program enhancements. I hear various suggestions: bake sales, sports tournament, trophies; awards. They’d like to have jackets stamped with their logo and maybe an end-of-the-year school trip. Robinson gets their attention with one booming “Hey!”

Funding has always been a problem for the group mentor. Before HUSO, Robinson was involved with Men Can Stop Rape, a national organization that mobilizes men to eliminate violence against women. He ran its Men of Strength Club at Facing History, a curriculum-based program on masculinity and violence. Yet the main office in Washington, D.C. gradually stopped following through with many of its promises, including support, supplies and site visits. It became harder to contact the higher ranking members and the pace of the program slowed as a result. The support structure for the program worked better for clubs in Washington D.C. than it did for those in New York City and Robinson’s frustration showed during the sessions. “Why are you upset, why don’t you just do it yourself?” the students asked Robinson. That’s when he founded HUSO. “Rest in peace,” was his response to the end of Men of Strength. He made the sign of the cross over his broad chest.

The funding roadblocks are a major hurdle for these programs at the primary and secondary school level. But long before they appear, orange cones and stop signs in the form of school boards and parent teacher associations inevitably get in the way because of the sensitive, often private nature of the topics the groups address.

Joanne Smith is better known as the Rabbit Lady to the elementary school children she teaches in Madison County, New York. Working for the Liberty Resources Victims of Violence Program based in Oneida, she runs a three-week program for kindergartners and second graders to teach them safety rules based on a “No, Run, Tell” concept. Smith brings in a rabbit to talk about different types of touches, especially those that are unsafe and unwanted.

After one cycle of such sessions, a second grader disclosed to a police officer that a neighbor had inappropriately touched her, saying “that the Rabbit Lady told me it was okay to talk about it.” Another time, following Smith’s “No, Run, Tell” rule, a kindergartner screamed and ran to the principal’s office after an older boy approached him in a bathroom stall. As a result, she said, “It is one of those programs that I will continue to do until the day I retire.”

Despite the success, the 10-year-old program is now only in eight of the 14 elementary schools in Madison County. Some schools cite budget cuts, others say their guidance counselors will conduct their own programs—which rarely happens—and sometimes parents express discomfort at the thought of their children talking about such touchy matters. Now, Smith is busy training a volunteer to relieve the time pressures involved in running such a program.

“Americans, we have such a bizarre relationship to sex,” Dr. Ballinger, who is also a friend of Smith’s, told me. He continued in frustration to recall a news story from the previous week. A woman was kicked out of a Victoria’s Secret store for breast feeding. “The media has a ton of sexualized images of women and men, but yet we can’t talk about it any healthy normal way.”

Utt has faced the same resistance when trying to talk to middle and high school students about positive sexuality. So he focuses his attention instead on college students. The middle and high school administrators, he says, “just don’t wanna touch it with a ten foot pole.” As a former high school teacher in Chicago, he understands the challenges—if any type of programming triggers emotional reactions in students who may be survivors of sexual violence, schools may not have the resources or counselors to respond effectively. “But most of the time,” he said, “it just seems like they’re afraid to open the door.”

So Utt tries to weave the topic into his other presentations. He discusses sexual harassment as a form of bullying, or uses gender violence and patriarchal oppression as diversity topics. Despite the hesitance shown by parents or administrators, the reality is that these kids are dealing with sex-related issues even in middle schools. There’s the media, first of all. Then, “the PTAs are like, ‘You can’t do healthy dating relationship stuff, our kids aren’t dating!’” Utt told me, “Actually they are . . . I know they like to pretend they’re not.”

Even if he does gain access to a school’s classrooms, he wants to continue the conversation after he leaves. Utt says that probably only 30 percent of schools have a real interest in incorporating his training or presentation into the curriculum or into community dialogue. The other 70 percent of the time is just checking a box, he said. So to go a step further, he relies on social media, and will openly answer any questions students may post.

Avoiding such discussions has adverse consequences for the quantitative study of sexual crimes. Before Dr. Christopher Krebs became a senior research social scientist at RTI International, he taught criminology to college students. Several women approached him one day after class, sharing that they had been drugged without their knowledge. Dr. Krebs clarified that they had not been sexually attacked. Still, the what-ifs intrigued him.

“I was curious about that and started looking at the literature, and didn’t see anything that did a good job of trying to measure drug-facilitated sexual assault,” he said. “Nothing from a research perspective. No strong rigorous studies.” So he and his colleagues wrote a proposal to the National Institute of Justice. They planned to conduct a web-based survey of college students to measure the prevalence of this crime among college women. “It is something that is unacceptable and we should be doing more to get those rates lower,” he said. “The data information would do more to prevent violence.”

Since then, he has done extensive research on intimate partner violence, sexual violence, corrections, criminal justice systems and program evaluation. He works for numerous organizations, including the National Institute of Justice and Bureau of Justice Statistics, which publishes the National Crime Victimization Survey. But he also noted that “there are significant shortcomings related to the quality of the data on rape and sexual assault.” So he is wary of drawing any conclusions at this point. Still, he acknowledges the bureau’s continuing efforts to quantify the number of attacks.

All of the male advocates I spoke with talked about how overblown the praise they receive can be for working with young men to change their attitudes and behavior. As Gómez explained, “It’s really easy for that to be really sexy and romantic and everyone says how fucking great and how brave it is and they want to put us on TED and just go up in this whole thing.”

Of course they have their detractors. Gómez casually mentioned the death threats he’s gotten from men’s rights activists, but how they are nothing compared to the harassment heaped almost daily on his feminist friends. For writing blog posts and talking about sexual violence, their pictures are posted up on websites with cash rewards if they’re raped and killed, with names of their kids underneath, with “horrific racist xenophobic sexist horrific threats,” he said.

“I think it’s an uncomfortable thing because I think there is a credibility and there is a quiet that I get where men listen to me in a way that they will never listen to a woman,” he said. “It’s completely fucked up and it’s completely connected to patriarchy and sexism and everything else.”

In early 2014, at the Brooklyn Museum, “Mother Tongue: Monologues for Truth Bearing Women, For Emerging Songs and Other Keepers of the Flame” brought together artists, activists and writers in a conversation about violence against women in black communities. Nearly a dozen women shared stories of rape and abuse to an audience of several hundred men and women. In the last part of the evening, four men who advocate for women’s rights stepped onto stage to talk about accountability, a word often used in sexual violence prevention work.

For Quentin Walcott, an anti-violence activist who works at CONNECT, accountability is the answer to rape culture. For Darnell Moore, a writer from Bedford Stuyvesant, it means recognizing that while he is oppressed as a black man, he is also the oppressor of women. He described oppression as the act of standing on another person’s neck. It’s easy to recognize who is pressing down on our shoulders, he said, but the hard part—the accountability factor—is not only recognizing who you’re standing on, “but what you realize after you get your feet up.”

One afternoon at the meeting in Room 227, the group starts to argue about the value of money. Sentences overlap and the boys grab at any second of silence to shout out their opinions. One asks the others if they would rather have a small home full of friends and family with only enough money for necessities, or a huge house full of strangers with unlimited funds. As they debate, Robinson listens. He waits for the right moment to jump in and when he does, some of the boys are too involved in conversation to hear him. “Yo yo yo one mic, one mic,” a few call out. The rest stop to give their mentor the floor.

Robinson doesn’t have to ask for their respect; he’s earned it. “I’ve had teachers that don’t come from the same type of environment as these kids, and they’re like, ‘Wow, Courtney, how do you do that? You ask them to do something and they do it!’” It’s simple, he says. He doesn’t dictate; he explains. When discussion centers on the words “female” and “bitch,” Robinson doesn’t respond aggressively when a student says that he only uses “bitch” because sometimes “she acts like one.” Instead, he puts the word into perspective, asking the boy how he would feel if that word was used to describe his mother or sister. “Regardless how you feel about her, somebody loves her,” Robinson reminds the student. “And there isn’t anything you can say to justify how you’re treating her.” They listen.

The group’s members also know that when Robinson was asked to leave Facing History and become the New York supervisor for Men Can Stop Rape, he turned the offer down to stay with them. This is why: “Me seeing y’all and me being here to support you all, and seeing you all graduate and move forward and be able to deal with your problems and help you all make it through and give you all advice means more to me than whatever dollar amount they were going to give me.”

“That’s love,” one of the students says. And the rest clap.