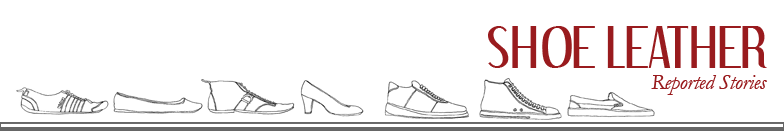

Kevin Tussy stood near the floor-to-ceiling windows of his apartment and looked out at the derelict neon lights of downtown Las Vegas, his oblique expression alternating between passion and irritation behind the lens of his Google Glass. With a few flicks of his finger across the Glass temples, he zeroed in on a colleague’s face. The Glass heated up as it located target points on the subject, sent the digitized eyes, nose, mouth, and cheekbones to an online database, and returned almost instantly with a set of profile matches. Tussy’s eyes seemed to roll into the back of his head as he momentarily focused on the headshots scrolling across his transparent lenses. Soon, he found the picture that exactly matched the man standing in front of him, Nametag developer Shawn Maguire. And with just one more tap, he had accessed all the available information on Maguire, everything either published by him or about him online.

“Your face is a unique ID that can be accessed at a distance,” Tussy would later say, hunching on the edge of his couch as he tried to explain how his new facial recognition application, called Nametag, could eventually be beneficial for privacy rights. “This is what makes it so amazing and what makes it potentially so scary for some people.”

Testing the NameTag app on Kevin Tussy

The term “facial recognition program” tends to divorce the implications of the app from reality, but this is what the developers envision happening within a year: Imagine standing in line at a coffee shop. Another person in the queue finds you attractive. Instead of walking up and talking to you, the person surreptitiously snaps your photo using Google Glass or a phone camera. Then, the software immediately matches your image not just to a potential prison record or public profile, but to everything ever posted, from tweets to Facebook pictures to LinkedIn updates.

Tussy has even more far-reaching plans for Nametag. Consider a police car trailing a suspect fleeing from the scene of a crime. The officer could scan the suspect’s face from the safety of a squad car, and determine if the suspect had a violent criminal history, or had registered a gun. Or, imagine a networking event, where recruiters are scouting for job candidates. Managers could scan the faces of professionals at the event, view their LinkedIn pages, and immediately identify and approach the most qualified people.

These examples of facial recognition’s potential paint it as a technology solely for the benefit of its consumers. However, most of the advance publicity about Nametag focuses on how seriously it can infringe on the right to privacy.

Some have labeled the app “stalker-friendly” since it automatically includes information about all individuals without their initial permission, even if those people aren’t aware of Nametag at all. Google has banned facial recognition technology from officially operating on its Google Glass software, stating in a blog post that it will not add these types of features to Google products “without having strong privacy protections in place.”

Nametag exemplifies a startling modern truth: technology has created a virtual souk for personal information, and many of its customers aren’t aware that they’re bartering with their data.

While developers like Tussy and his colleagues can build and release an application as sophisticated as Nametag in the space of a few months, lawmakers, who began February 6 to act on suggestions from the Obama administration offered two years ago, will debate much longer before they even begin to propose policy to govern this new technology, let alone pass it into law.

The work being done this spring and summer by the National Telecommunications and Information Administration is only expected to yield suggested guidelines and urge companies to develop and adopt internal recommendations for best practices. There are currently no U.S. privacy laws governing facial recognition technology and enforcement is not even on the table, making privacy more a currency than a right. For the time being, people concerned with keeping what’s private, private, will have to find ways to protect it themselves.

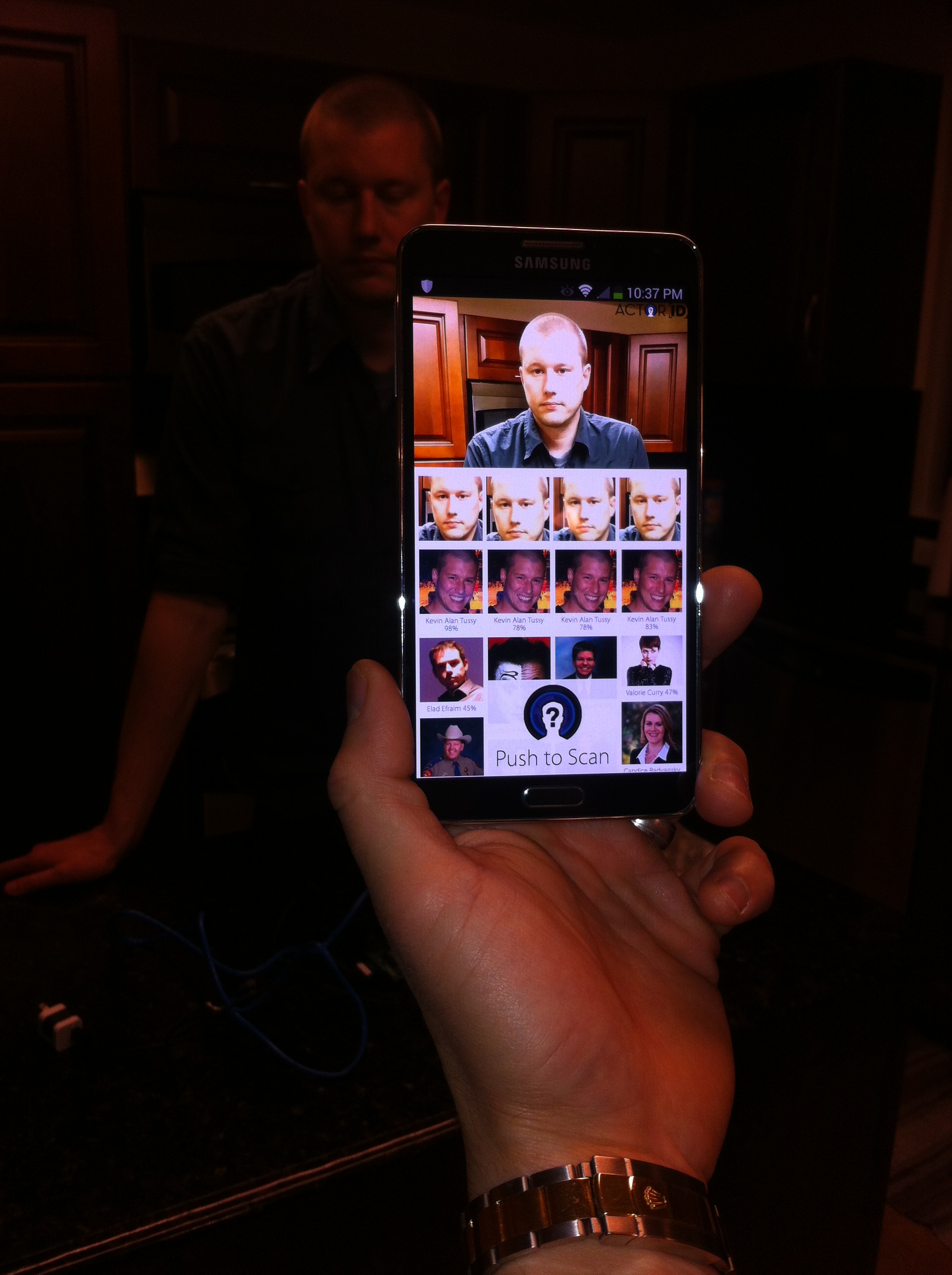

Lindsay MacVean, COO at Nametag, thinks that his company is helping people take privacy management into their own hands. When asked about how he’s dealt with Nametag’s privacy issues, MacVean pointed to a small poster on a column in the center of the apartment. Three “Privacy Rights” and a short note scrawled on the poster in Sharpie declared:

- The fundamental right to know who has their personal data information and how it is being used!

- The fundamental right to control who gets their personal information and who it is shared with.

- The fundamental right to know our information is secure.

Nb. A face can be identified in secret and at a distance.”

Tussy and his teammates self-styled their own privacy rules as a way to self-regulate their company and eventually make their app more appealing for privacy-wary users. For now, they have released a beta version of Nametag for select Google Glass Explorers, but have delayed full release until after the National Telecommunications and Information Administration completes its discussion of privacy guidelines over the coming months.

When Nametag eventually goes public, it will be free of charge. Instead of paying with credit cards or PayPal, users can only scan others’ faces and access profile information by providing their own data. This will give the app a large library of profile information to attract advertisers. Nametag asks users to connect social networks and input information such as job, relationship status, and hobbies. Whether they read the contract or not, people who download the Nametag app will be trading their personal information for this novel technology.

Tussy doesn’t think that there is anything wrong with that transaction. For him and many other developers, the only viable way to have privacy now is to actively police your personal information through technology. In fact, users can only gain control over the information on their Nametag profiles by signing up for the service and editing the profile that Nametag will automatically create from data already on the Web.

“You choose how much information is exposed when someone scans you and you'll be reciprocated with the same amount of information about that person,” said Tussy. He compared the interaction to meeting someone for the first time: if one person introduces himself with both a first and last name, the other would reply with the same. “We hope that people that are concerned about their privacy are some of our first users because of the identity or information exchange that we’ve created, which is much better than any feedback loop from a Google, Yahoo, or Bing at this point.”

By that, Tussy means that search engines like Google don’t offer the option of removing certain private information from search results. Nametag allows that, but only after users discover the service and sign up. At that point, users can get selective about what appears in the profiles that Nametag already has generated. If users want to avoid having a profile on Nametag altogether, they must go to the Nametag website and personally opt out of the service. Although this policy dismays privacy advocates, Tussy maintains that most apps automatically utilize all personal information available on the web whether users subscribe to the service or not. It’s the unfamiliar facial recognition aspect that makes the unfairness of the policy more obvious and more controversial.

MacVean said from monitoring online comments about Nametag, he knows that some people “have already constructed a preconceived notion of a dystopia” that the Nametag team has never said it would create or in some cases, couldn’t anyway. “So I think that we're just going to keep acting responsibly and earning the trust of our customers and the community at large.”

Developers working on programs at the DeveloperWeek Hackathon in San Francisco

Tussy and MacVean think misconceptions about Nametag’s intent, widely circulated when the app was first announced, comes from people thinking that it is like something they’ve seen in a movie, “like it could work in a dark car or an alley.”

And yet, Tussy said that anyone being scanned is also very likely to be aware of it. “In some cases,” he said, it’s easier to scan someone with a cell phone, since so many people use them that way, and “if you have Glass on--at least now--it’s so conspicuous.”

Conspicuous, yes, and already facing media and public backlash even though now only a tiny fraction of consumers own Google Glass. The term “glasshole”--Google Glass users who do things like snap pictures of others without their consent or use Glass to reply to emails during conversations--has become so ubiquitous that Google felt the need to issue an etiquette guide for the product. Many bars and restaurants are banning Google Glass and an AMC movie theater in Ohio even called the Department of Homeland Security when a man wore his Google Glass in the theater. Google has even banned facial recognition applications on Glass for now, although developers can easily re-engineer the device to install programs that are officially banned.

Despite the current controversy surrounding facial recognition in general and Google Glass in particular, there are companies and developers betting that the technology will soon become as widespread and eventually as ordinary as cell phones. In the words of David Martinez, a Google Glass developer at Bricksimple, “It's going to run over this country like a truck.”

That’s probably hyperbolic, but the dozens of facial recognition applications currently in development foreshadow the day when the face becomes a universal form of technological identification. Even those with extensive plastic surgery may not be able to evade identification. Developers have created programs that can identify a face based on close analysis of a few very small regions usually not altered by plastic surgery. That technology worked with nearly 80 percent accuracy when tested on before and after photos of patients who have had reconstructive surgery.

Tussy sees facial recognition software as “the true opportunity it is, where this technology can be used to walk into a store and pay for an item, your car could recognize your face to start up and if your kid gets in there, even with the keys, it won’t start,” he said. “There’s an enormous, almost unlimited, amount of uses for this type of tech to do good.”

In addition to Nametag, Tussy and his team are developing eight other facial recognition applications not yet announced to the public. He would outline them only vaguely but offered that “some of them will be to help people with medical or memory issues. Some of them will be to help professors know who their 300 students are, what their attendance was, what their last grade was. Some of them will be to help the doctor scan a patient.” Most exciting to Tussy is a new “entertainment app” that he hopes will be “a way for us to introduce facial recognition to a lot of people in a way that is not scary at all, and doesn’t have any privacy concerns.” By introducing a more palatable app early on, Tussy hopes to make consumers more comfortable with more invasive facial recognition technology later.

Many other companies are testing out similar programs for Google Glass. These include San Francisco’s Lambda Labs, the startup of 24-year-old Stephen Balaban, and the facial recognition service of the computer vision company Orbeus, called Rekognition. In San Diego, police are testing mobile devices that scan and identify faces based on mugshot and driver license databases. Most recently, Facebook announced that it is testing new software called DeepFace that uses a 3D modeling system to correctly recognize human faces with 97.25 percent accuracy. An actual human being can recognize faces only a quarter of a percentage point more accurately.

Time, personal obsession, and creative thinking trump money, raw resources and legal advice when it comes to creating technology, so new programs are as likely to emerge from three-person teams who meet up at hackathons as they are from multibillion-dollar corporations. Often, the little guys like Nametag have the sharpest edge.

I met up with Martinez at a hackathon in the offices of Rackspace in San Francisco this past February. We were talking about the effectiveness of small companies in the realm of big ideas. “Larry Page said a long time ago, you don’t worry about corporations. You worry about the two guys in the garage. Larry Page started Google as one of those ‘two guys in the garage.’ Those are the guys that will take tech giants down, all day, every day. That's why everybody at Google is buying everybody. They buy them because they're scared of them.”

It was DeveloperWeek and more than 220 attendees had gathered to work for 30 hours on mobile and computer applications that would later be judged by a panel of representatives from tech companies like Evernote. Developers and HR representatives huddled over laptops and mingled around tables loaded with free food and energy drinks. Many of the developers complained about the Rackspace offices closing at 8 p.m. since hackathons usually will go uninterrupted for as long as 72 hours. Part of the appeal of the contest is to work as long as possible without sleep.

Company sponsor tables at the Developweek Hackathon

Nonetheless, developers still managed to create a series of interesting new programs. Those recognized in the closing ceremony included an app called Firefly that provides personalized healthcare portals through which users input their health records to find the insurance plan that best fits their needs, and another named Airshare that connects people based on their flight itineraries so that they can split cabs to the airport.

Finished applications, however, are never the main purpose of hackathons like DeveloperWeek. What they really do is connect developers with similar interests who will then go on to spend weeks and months working in apartments and rented office spaces, often without sleep for days at a time, to create new applications from scratch. The hope is that these inventions eventually sell to larger companies for thousands, if not millions, of dollars.

And that is one of the reasons the Nametag team hasn’t shied away from controversy, which has been translating handily into free publicity. They feel so confident that the law will not catch up with them that they haven’t even bothered to correct erroneous depictions of the app that have appeared in the media. For example, there was a claim that Nametag could be used to scan someone’s face in real life and match that face to a private online dating profile, which Tussy said was not actually possible.

He talked a little about the company’s publicity strategy in terms of the desire to create controversy. “If we go out with an app that makes everybody 100 percent comfortable, are we going to get a hundred articles written about us a month? Are we going to get in Fox News and The New Yorker?” Tussy was actually pleased when he received an open letter asking him to delay the release of Nametag from Sen. Al Franken, D-Minn., chairman of the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Privacy, Technology and the Law.

“We never thought it would get a senator to write me a three-page letter, basically saying that this app is too powerful, please don’t release it, but that was a pleasant surprise,” he said.

The letter brought its own round of media attention to Nametag, but it also underscores the powerlessness of the law. Franken could only request, beseechingly, that Tussy delay the release until the NTIA completes its review. It was in an open letter to Franken in February that Tussy agreed to “seriously discuss the possibility of delaying the app.” By March, the team had decided to delay the release for the time being.

The phrasing in Franken’s letter reveals not only the extent to which even little companies like Tussy’s can operate in a legal vacuum, but also the central role they will play in the laws or policies that will eventually govern this new technology. The senator wrote:

Tussy is confident that Nametag operates within any eventual legal framework. No current laws prevent social media companies from gathering information already published online. “Our legal team and [former New Jersey Superior Court Judge Andrew] Napolitano has backed us up on television with regards to that.”

Tussy is referring to a segment on Nametag that appeared on Fox News in which Napolitano argued that the Fourth Amendment only protects an individual’s right to privacy from the government, not from other individuals or from corporations. Even the Fourth Amendment’s protection of privacy from the government is weak. The 1967 ruling Katz v. United States found that the Fourth Amendment only provides protection if there is a reasonable expectation of privacy that would be viewed as legitimate by society. People can have that expectation in their own homes, but does any expectation of privacy exist when information is stored or sent over the Web? The legal system hasn’t really answered that question.

Before digitalization of documents was the norm, the Supreme Court made a series of decisions ruling that one no longer had an expectation of privacy or protection from the Fourth Amendment after documents had been shared with a third party. That applied to records of dialed telephone numbers and bank records. Now, people tend to send huge amounts of personal information through third-party websites, from emails to banks to documents stored in cloud companies like DropBox.

Those 1970s-era Supreme Court precedents still apply, and apply on a much broader scale. Technically, they allow the government to look through personal emails and other digitized data without a search warrant. Another new complication: it used to be that people could only access the private, personal information of others by breaking into a home or office--by breaking the law. Now, information can be “stolen” through the interception of data online or the selling of data from company to company to company, which in most cases is completely legal. Digitization of data has made the Fourth Amendment obsolete and in most cases irrelevant.

It doesn’t look like the legal system will catch up with digitalization any time soon. As Tussy said, “I think that by the time the laws catch up with the technology the cat will be out of the bag, and I think it already is. I don’t think that--and this is just my opinion, that laws can really hold back technology. It’s very tough to do.”

Stephen Solomon, an expert in privacy law and associate director of the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at NYU, agrees. “Legislation in this kind of area always lags far behind because technology moves so much faster than lawmakers,” he said.

The sluggishness of the legal system in this case is compounded by the unusual interdependence of privacy law and public opinion. In order to win a privacy case, Solomon said, you have to show that the infringement of privacy would be “highly offensive” to a reasonable person. The idea of a reasonable person is based on the opinions of the majority of people in society, so as popular attitudes about privacy change, privacy law changes as well. When the legal system finally does address the privacy issues stemming from recent technological developments, attitudes toward privacy may have become so ambivalent that very little privacy violations would be considered offensive under this statutory standard.

“A lot of things that your generation finds acceptable in terms of sharing content another generation wouldn’t conceive of,” said Solomon. “The concept of privacy is moving in the direction of more things being shared.”

Consider what could happen when speaking to a friend privately over lunch, in a near future when technology like Google Glass is widespread and more socially acceptable. You might share personal information that you would never consider posting to Facebook or writing about in a public forum. Yet your friend’s Google Glass could record the entire conversation, and pass along that data to Google’s advertisers and affiliates. That’s something you never agreed to, and probably never would.

Shawn Maguire demonstrating Nametag on Susannah Griffee

Although that scenario looms in the near future, a similar interaction already takes place on Facebook. When people talk to each other over Facebook’s seemingly private messaging service, most assume that those discussions are private. In fact, Facebook can read every single message sent over its service. It can even read the sentences that users type into a dialogue box and then delete and decide not to send -- the impulsive replies that people might think of inside of their head but never utter in a conversation. If users are on Facebook at all, they agreed to Facebook’s terms of use, and everything Facebook does with their information, publicly posted or not, is legitimate.

Technology companies can legally get away with using consumer data almost any way possible by creating lengthy and confusing user agreements. Clicking the “I agree” checkbox on the terms of use often means giving up almost all rights to any information a user sends over the service.

“Facebook has good lawyers, what you think is a violation of privacy they’ve got covered because you clicked that box,” said Solomon. Facebook and tech giants like it create so many provisions in their user agreements because they potentially have so much to lose. “Can you imagine a class action lawsuit from abusing people's privacy when they haven’t agreed to it?” asked Solomon. Companies like Facebook and Google engineer their user agreements so that such suits would never stand in court.

Nishant Patel, the CTO and Founder of the mobile and web application engineering company Raw Engineering, also thinks that signing those terms of use contracts basically amounts to “giving up your basic right to privacy.”

His colleague, Gal Oppenheimer, the company’s product manager, agreed. He said that by signing up for, say, Gmail, users agree to let Google read any emails they send or receive over the service. “That's something that developers understand, and anyone who works in tech understands,” Oppenheimer said, “the customer for a Gmail account is the advertiser and not the user.” In other words, the company has no interest in protecting the privacy of its users.

“But I would say that the average person using a free email account doesn't understand that,” he went on. “So if you were to not read the fine print saying you were allowing someone to come and shoot you in the head, does it mean that they should be allowed to come and shoot you in the head?”

Many users, though, don’t really have a choice in signing the user agreements. There are two huge obstacles standing in the way, Solomon said. First, the user agreements are so long and obtuse that no one bothers to read them, and second, “what’s your alternative?” For many, sites like Facebook are vital tools for maintaining relationships and even professional networks. No other alternative currently possesses anywhere near Facebook’s user base volume.

“It’s kind of a monopoly,” said Solomon. “Do you really have a choice not to click that box?”

Currently, most people don’t even understand the choice they are making by signing up for Facebook and agreeing to its user agreements, and most developers think lack of public education regarding the far-flung implications of terms of use policies is one of the most important issues in technology and privacy law.

Developers like Martinez sometimes rant about the profligate ignorance of non-techie consumers. “Users like yourself and the rest of the public don’t understand that every time you download the app on your phone, it says accept or read the terms. But you don’t read it. Nobody reads it. What you're accepting, you’re accepting to giving away all your personal life, the people you interact with, everything you do in life, every piece of information that you handle through that phone.”

As Martinez lectured, he shook his smartphone in my face. “They have the right to read your email, they have the right to read your texting, so don’t complain that you gave up your privacy because you did willingly, because you didn’t read the fine print.”

Beyond just not reading the fine print, Martinez thinks the public doesn’t know or care what it’s giving away. Even Edward Snowden’s revelations that the NSA engaged in widespread surveillance of U.S. citizens haven’t changed people’s technology habits, he said. “The NSA was probably the biggest blow in the face you could possibly have and it didn't affect anyone, people didn’t do anything. So even if a nuclear bomb goes off in the middle of America and kills six million people because of a security issue and a privacy issue, I don't even think that would change anything.”

Lack of awareness and legislation with respect to privacy issues aren’t the only concerns. Even in those areas where strict laws protecting data exist, as in health care, the existence of legislation doesn’t stop hackers. Oppenheimer, at 25, the youngest developer I spoke with, gives an example of how data could easily be stolen. He thinks that while HIPAA is a well-enforced law, a hacker could easily intercept healthcare information by getting a job as a computer technician at a large company, something Oppenheimer says is not difficult to do. The technician could then install something between the computer and the network that “allows him to get every piece of information transferred to that network without anyone realizing it.”

He also thinks that those who’ve grown up using the Internet, starting with his generation, have no expectation of privacy. He lives his life as though everything he does in public or online is being monitored. If he wants to have a private conversation, he will meet someone in person in a secluded room.

There actually may be ways to create “secluded rooms” online, as companies are recognizing a consumer demand for privacy. These companies seek to distinguish their services by self-regulating their use of data and encrypting user information so that it is not even visible to companies in the first place.

Lindsay Macvean, COO at Nametag

Nametag COO MacVean thinks that this approach might work better than blanket legislation, since “there can be a certain danger in preemptively legislating for hypothetical situations particularly because lots of rules don’t necessarily fix the situation.” He was referring to FTC Commissioner J. Thomas Rosch’s dissenting statement to the 2012 FTC report, “Facing Facts: Best Practices for Common Uses of Facial Recognition Technologies.” Rosch advised that the FTC avoid general legislation on facial recognition in favor of a common sense, case-by-case approach in which companies create and agree to follow customized internal privacy policies.

Oppenheimer agreed with Rosch’s dissent. He thinks that the technology industry should create its own privacy guidelines in the same way that the film industry rates movies. Generally, a film company chooses to submit a film for a ranking, the movie receives a ranking, and movie theaters choose to follow that ranking. A movie theater can disagree with the ranking, like in the case of the film Bully. That movie received an R rating, but because it was meant to educate high school students about the dangers of bullying, AMC theaters decided to allow those under 18 into the film. That kind of flexibility wouldn’t exist if the MPAA system was legally binding.

Google ad targeting, for example, already self-regulates along guidelines that are specific to its operations. An advertiser can try to narrow its target down to women who speak Spanish and have been to Germany and have children. But if the client tries to narrow the demographic further, by, say, requiring that the consumer also be 24 years old, have blonde hair and enjoy coffee, Google would tell the advertiser that the demographic is too specific. Oppenheimer recalled a search he once did that made the demographic so specific that the pool involved only about 50 people. ”You could figure out who those people were based on who you were targeting,” he said. That type of specific regulation for every technological service would be almost impossible to implement through the legislative system.

“What should be built,” Oppenheimer said, “is not the specifics of what you can and cannot do, but the guidelines you must follow in terms of ideas, sort of the way the FCC does it with antitrust law.”

The U.S. government is currently wading through the earliest stages of what might become a broad set of privacy principles resembling Oppenheimer’s vision. In 2012, Obama’s administration outlined a Privacy Bill of Rights, which set the future goal of creating statutory privacy rights for individuals. Eventually, Obama hopes that companies will be legally obligated to create specific internal privacy policies that comply with broader federally mandated rights.

As the federal government has made no progress in creating statutory privacy rights that can be legally enforced, the NTIA has gone forward with meetings concerning company-specific privacy guidelines. The first NTIA meeting to discuss privacy rights, on February 6, discussed in vague terms what privacy issues companies should keep in mind when developing facial recognition technology.

In prepared remarks at the NTIA meeting, Lawrence Strickling, who is the Assistant Commerce Secretary for Communications and Information, urged companies to begin discussing how to notify consumers that their biometric data is being collected, how to let consumers control their data, and what actions to take if databases of images and information are hacked. Strickling further said that he hoped the NTIA could work with companies to develop ways to apply the Privacy Bill of Rights to facial recognition technology. However, without any actual legislation in place, companies have no obligation to follow any principles outlined by the NTIA.

As legislation and even public awareness concerning modern privacy issues languish, more new technology like Tussy’s Nametag goes on the market and the innovation gap -- the time period between when new technology is released and when law cracks down on that technology -- grows wider. “Is it better that it takes a long time to get the laws passed so that we can have time to innovate before they say, shut things down?” asked Tussy. He paused for a second. “I would say yes. Not in say, all cases, in all cases I wouldn’t say that having laws take a long time to pass is a good thing, but in this case I'm grateful for the opportunity for us to innovate rather than have a knee-jerk reaction.”

Tussy himself had a knee-jerk reaction to Google Maps Street View, and felt uncomfortable about the app when it first came out. Yet after it helped him successfully locate his hard-to-find new dentist’s office, “the amount of value provided by that software outweighed that feeling that I had by so much that I never thought about it again, I would never give up that technology.”

“That’s what we believe we can do with facial recognition technology,” he said.

Martinez agrees that from a tech developer’s standpoint, the innovation gap has its virtues, but also conceded that the risks to users are real and present. “The tech companies, all the big corporations, the product sellers of mass quantities, they're massaging you right now and then they’re landing and you’re just accepting it,” he said, as if to suggest that only developers understand the dangers. “Forget the legal system, what are you going to do, wait ten years and the technology's already changed? By the time you get it to court that technology's already over.”

In various discussions with developers, I constantly asked how I could protect my privacy and most said it was impossible, or extremely difficult. But then Martinez corrected my phrasing. “You need to get off the word ‘protect your privacy,’ because that doesn't apply any more in this world. That's really a bad way to say it. What we want to do is be able to manage our privacy.”

Martinez compared managing privacy to installing an alarm system in your house. People need to actively protect their online data just like they install home security systems and lock their doors. A well-secured home stands a better chance of deterring a thief than one that is less protected. The same applies to personal data.

Privacy now is not a right but a currency, something to be banked and exchanged like cash, not defended like liberty. Yet few people approach privacy management with the same concern and care that they show for a monthly budget or a car purchase.

Google Trends, which measures the number of Google searches for key words, indicates that public interest in the importance of personal privacy has been declining since the reauthorization of the Patriot Act in March of 2006. Even the Snowden revelations in 2013 resulted in only a tiny peak in the number of Google searches for the word privacy.

Meanwhile, people constantly post personal information to social media sites like Twitter and Facebook, broadcasting positive or humorous moments to thousands of friends as well as companies trying to target advertising. Tussy foresees a day when those carefully cultivated personas that individuals tend to project on services such as Facebook and Instagram will evolve to more closely resemble the intimacy that grows out of relationships cultivated in flesh and blood. “When I saw Google Glass, and I've known about facial recognition technologies for a while, those two things clicked,” he said, “and I said this is the key to taking social media offline and making it work in the real world.” He thinks the “game” of people using online “as kind of their second life where everything's perfect, it’s all vacations and new cars . . .is ultimately unsatisfying, and damaging both in terms of lost privacy and less meaningful relationships.”

This is where, in an odd and somewhat subversive way, Tussy thinks Nametag can work to give users more control over the “currency” of privacy to produce a better relationship “product.” Using terms like currency and product in this manner may seem ridiculous, but technology often has a way of dehumanizing even the most human of concepts, from friendship to personal privacy.

“Americans have no idea what privacy is,” Martinez said. “They can barely use their phones. Do you have any idea what's running on your phone right now? Do you have any idea? You don't, do you?” asked Martinez. I didn’t.

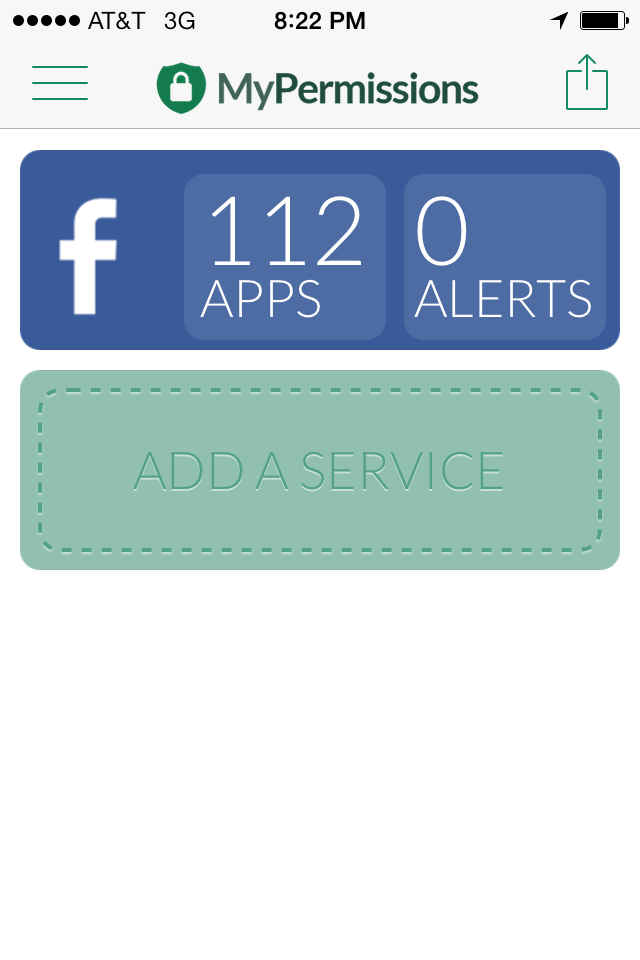

He thinks the only way to manage privacy today is to “use technology against technology.” To demonstrate, he pulled out his smartphone. On it was MyPermissions, an iPhone application that lets him see all the applications on his phone and to which other companies they were feeding data.

Running the device on my own iPhone revealed that 112 companies have access to my private Facebook information, many of which I don’t recognize or even remember subscribing to.

Martinez develops for Google Glass, so he gives the widest berth to Google Plus, letting 32 companies receive his data from the app. But he restricts other programs such as Facebook and LinkedIn, to no more than one or two. He thinks that apps like MyPermissions will replace the need for digital privacy laws.

“You would want that app right, you would use it. You would want to know who's looking at you,” said Martinez. “It's something that should have been there from the beginning.”

Instead, new technology swamped the market before the legal system could even blink. Consumers ate up new products, not asking why the apps were free or, as users, what information they ought to protect that they might be just giving away. And tech companies had no incentives to build privacy protections or systems like MyPermissions into their products.

Only mass education about the ways companies use personal data and privacy management tools like MyPermissions can reverse this paradigm. “There is a way to be private now. There is,” Martinez said. “But you gotta want it.”