In this view looking south from the meridian at Park Avenue and 56th Street, 417 Park is the low apartment building to the left. (Evelyn Cheng)

In the shadow of some of the biggest real estate deals and developments in Manhattan is 417 Park Avenue, a luxury residence that Emery Roth designed nearly a century ago. It is the last of 13 high-end apartment houses that once lined the 10 blocks between 46th and 57th streets, a stretch of the avenue now dominated by corporate towers. But perhaps not for long.

After a nearly 90-year hiatus in new East Midtown residential construction, a 96-storey condominium is going up at 432 Park Avenue at 56th Street, just two blocks north across the avenue from 417. Developers say that when completed next year, it will be the tallest residential building in the Western Hemisphere.

Plans are also underway for the area’s first new commercial development in more than 50 years. Despite the City Council’s decision last fall to thwart the East Midtown Rezoning Proposal, the Department of Buildings approved plans in February for a 41-storey office tower at 425 Park at 55th Street. Construction is expected to begin next year.

Little of this development news means much at 417 Park, where a succession of residents over the past 97 years have watched the area’s bit-by-bit transformation from an upscale medium-rise residential neighborhood into an avenue of glass and steel. This 13-storey limestone hold-out provides the perfect vantage point for considering both the history and future of New York City’s East Midtown district.

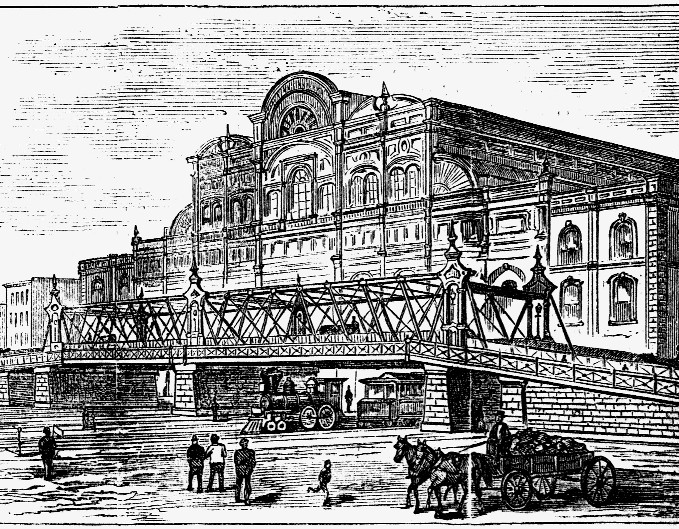

The Steinway factory before 1873 at 53rd Street and Park Avenue where the Seagram Building stands today. (Joseph Brennan)

In the late 19th century, members of New York City’s upper class had migrated north from the Gramercy Park area of 23rd Street to 40th and 55th Streets around Park Avenue. They built mansions and townhouses on the western side of the thoroughfare, mostly in the area south of 42nd Street. On the eastern side, across railway tracks from the then Grand Central Depot, stood the flats and brownstones of the middle and lower classes.

For several decades, residents smelled the soot and smoke generated by the trains, which then ran at street level. After many safety and health complaints, the railroad, then owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, began a large project in the 1870s to submerge the trains. By 1875, most of the tracks were laid in semi-tunnels that were vented to the open air along the middle of Park Avenue between 56th and 96th Streets. South of that, from 56th to 49th Streets, the tracks were not in tunnels but positioned two feet below road level and completely exposed to the air. Pedestrians crossed the railroad via iron foot bridges at every street intersection. At 45th and 48th Streets stood similar foot bridges, beneath which the trains ran at ground level.

This November 21, 1874, issue of the Scientific American showed a footbridge just north of Grand Central Depot.

Yet even with these improvements, the steam-run railroad still disturbed the neighborhood. The passengers were no happier, mostly confined to hot, sooty tunnels during their commutes.

In 1899, William Wilgus, a civil engineer for the New York Central Railroad, proposed electrification of the trains and their tracks and covering over the rail yard to improve conditions. But it took a fatal train crash in 1902 in the Park Avenue tunnel at 56th Street for the state to turn Wilgus’ plan into a legislative mandate. The resulting law gave the railroad the incentive to rework the entire transit system.

By 1908, Wilgus had completely submerged the rail yards surrounding the station and reconfigured the flow of the trains to create two levels of tracks, one below the other. The railroad company financed the new Grand Central Terminal building by selling parts of the new “land” that covered the trains, actually a platform supported by columns that reached the bedrock. This resurfaced area evolved into the broad, two-lane roadway and grassy, flower-bedded meridian of today’s Park Avenue and the subsequent development on it became known as Terminal City, which included luxurious hotels like the Biltmore.

Other new residential structures in the area were built as “apartment hotels” with ground-floor kitchen and dining areas for residents. This terminology was not used because they were hotels, per se, but to avoid the restrictions of New York City’s multi-unit housing regulation, then called the tenement law. Even if the buildings qualified under this designation, the connotation of “tenement” as overcrowded housing for the poor held little or no appeal to the well-to-do residents developers hoped to attract. More literally, the term “apartment hotel” also referred to new groups of dwelling units with fewer rooms and communal dining areas that catered to a commuter class of people who wanted a posh pied-à-terre in the city in addition to their suburban manses out on Long Island. At the time and for many years thereafter, New York apartments were almost all rentals.

Despite the legal tangles, developers saw a business opportunity in upscale residential housing that Roth was also quick to embrace as architect and sometimes stakeholder. These collaborations resulted in the elegant towers of the San Remo and the Beresford along Central Park West, which are Roth’s work. A number of other luxury buildings on the Upper West Side still proudly promote their connection to him in real estate ads.

Wealth is inseparable from grand architectural projects, especially for those in Manhattan. With affluent clients like the influential Hearst editor Arthur Brisbane, Roth and architect Thomas Hastings designed the 41-storey Ritz Tower in 1926, an apartment house on the northeast corner of 57th Street and Park Avenue. It was the first skyscraper apartment building. New luxury apartment buildings have continued to appear on this street further west, most famously One57, a popular choice for international investors that is expected to be completed later this year. But Roth was the first to bring New York’s wealthy from their townhouses to apartments in the skies during Park Avenue’s earliest wave of development.

In a drastic shift from the apartments designed by Roth and his contemporaries, subsequent construction has been purely corporate. The 1951 Lever House by Gordon Brunshaft for Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, and the 1958 Seagram Building by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson both caught public attention not only for design innovation but for disrupting the uniform wall of side-by-side limestone apartment houses that lined this part of the avenue. Other glass towers soon joined them, gradually replacing the ornate stone buildings, and in time, the Seagram Building and Lever House receded into the cityscape.

Now, after a lull of half a century, comes the first break in the corporate tower trend. With the support of developer Harry Macklowe, architect Rafael Viñoly designed a thin, rectangular tower for 432 Park that broke ground in 2011. When completed, it could give some of the world’s rich a more stunning aerial view of the tri-state region than from the top of the Freedom Tower at Ground Zero, known officially as One World Trade Center. Without its 408-foot spire, the tower is 1,368 feet high, just shy of the 1,396 feet of 432 Park. Viñoly’s building stands on the site of the former Drake Hotel, which Roth designed in 1927, towards the end of Park Avenue’s residential construction heyday.

Having started his architectural firm in 1902, Roth was just beginning to venture into designing luxury apartment buildings when the first major one in that section of Park Avenue was built in 1907. Standing east across the avenue from the then future site of the Drake, the Mayfair Apartments were not Roth’s work but that of Charles Rich, a partner with Hugh Lamb in one of the previous generation’s leading architectural firms. If Roth’s mark on the city would be high-end residential towers, the Lamb and Rich legacy was ornate apartment houses and townhouses. The pair also designed commercial buildings as well as Theodore Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill house on Long Island.

The Mayfair set the precedent for the 13 luxury, medium-rise apartment buildings built over the next 20 years in the 10 blocks of newly created lots that covered the train tracks just north of Grand Central Terminal. These rectangular blocks included work by other notable architects of the era, such as Warren and Wetmore and Julius Harder.

The early dealings behind the block and lot of 417 Park are outlined in a 2014 book, New York Transformed: The Architecture of Cross and Cross, by New York architect Peter Pennoyer and his collaborator Anne Walker. As they tell it, developer Swan Brown Company once owned the entire Park Avenue block front between 54th to 55th Streets. In 1911, the firm engaged Roth’s contemporaries, Cross and Cross, to design 405 Park, an apartment building at the southern corner of the block. Next door, Cross and Cross made plans for a two-story carriage house, which guaranteed daylight to the adjacent apartments. The architectural firm also had plans for the northern corner, where 417 stands today, but the developer’s foreclosure in 1916 put the lot into the hands of Roth and his backers, Bing and Bing.

Roth’s steel-framed, limestone structure at 417 Park broke ground in 1916 and was finished a year later. Development, however, could hardly keep up with the demand, said a New York Times article from 1917 headlined, "Real Scarcity in Apartments this Year; Everything Filled at Higher Rates: Park Avenue Section Only Centre Showing Normal Building Conditions." The article pointed out that six new buildings had been built on Park Avenue the year before.

Some of the roar of the 1920s emanated from such storied New York landmarked addresses as the nearby Plaza Hotel, St. Bartholomew’s Church and the Racquet and Tennis Club. The Park Avenue apartment houses south of 58th Street were just as much a center of the New York social life of the period. A bridge tournament Harold S. Vanderbilt hosted in the Ritz Tower in December 1930 warranted full-blown coverage in the Times. In November 1926, the newspaper also reported that "Mrs. Edward de Clifford Chisholm of 375 Park Avenue [now site of the Seagram Building] gave a luncheon yesterday at the Colony Club for her debutante daughter, Miss Sara H. Chisholm." The newspaper’s announcement pages note the many other debutantes with home addresses in these buildings and their subsequent weddings at St. Bartholomew’s, just four blocks south of 417 Park.

Dau’s Blue Books from the period show that the early residents of the apartment building included the nephew of Solomon Guggenheim and the great-grandparents of Tommy Vietor, who was the National Security Council spokesperson under President Obama. The elder Vietors’ names also appear on the list of 1920s trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ancestry.com records contain the names of many maids and butlers for the residents of the building, mostly from Finland.

The residents of 417 were frequently mentioned in the New York Times. The women generally held dinner parties, while the men were mentioned for their financial transactions or their obituaries. In 1918, one 11th floor resident placed an ad in the Times looking for a “Lady’s Maid” who “must be a good sewer and have first-class references; going to country in June.” A “Mrs. Ernest H. Miller of 417 Park Avenue” founded a new magazine in 1928 called Cabaret Stories, self-described in the paper as a publication “of night life, mystery, fiction, fact and fancy of the cabaret world.”

Even as late as 1958, the newspaper reported that a resident of the building at the time, Mrs. Stephen Sanford, was holding a meeting at her home to plan an embassy ball for the children’s fund of the King and Queen of Greece. Another past resident was Washington Dodge, a survivor of the Titanic and the former financial editor of Time Magazine, according to his 1974 obituary in the Times.

But luxury living in this and every other section of Park Avenue soon gave way to the financial pressures of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the commercial boom after World War II. While 417 initially sought to lower costs for financially strained tenants by dividing the full-floor, 16-room apartments on the top four floors, residents of other buildings often had to move out of the area. Especially after World War II, some had to leave their apartments because their landlords didn’t renew the leases. The post-war economic growth often meant that a tall office tower in East Midtown was more valuable to developers than a mid-rise apartment house.

In this 1927 photograph looking south on Park Avenue from 56th street, 417 Park stands just behind the low building (the future 425 Park) on the left. (New York Public Library)

Images of Park Avenue near Grand Central Terminal before the 1940s show a wide street with a uniform line of buildings that all resemble 417 Park. But one by one, the buildings were torn down, starting with the Mayfair in 1946, which made way for the region’s first office tower, the Universal Pictures Building at 445 Park Avenue. Within 50 short years, corporate development transformed the area, leaving only old photographs to show the stately residential feel that this part of Park Avenue once had -- much like the avenue still has less than a half mile further north.

As that first office tower went up, the developers of 417 Park saw the future and wanted to evict its residents in favor of commercial use, a 1946 New York Times article reported. But the tenants waged a counteroffensive by sending a lawyer to protest the eviction application at the New York District Office of Price Administration. Another article from the New York Herald Tribune about the case told how the lawyer “read letters from tenants who said they had their families’ families living with them” and said that 14 of the tenants were veterans. By December of that year, the tenants had negotiated to buy their rented apartments from the developer, thereby turning their building into a cooperative. This governance change meant that each apartment owner had a proprietary lease linked to shares in the corporation that owned the building. A board approved new residents and voted on decisions such as structural alterations and fielded offers from developers -- at least five in the past 24 years, some in the 12-figure range, said Nikola Dusovic, the building’s resident manager. Every time so far, the answer has been no. “This building,” he said, “is going to stay where it is for a very long time.”

To turn 417 Park into a commercial property, a developer would have to buy out the cooperative by getting the votes of 100 percent of the residents approving both the decision to sell and the sale price, building manager Janet Roman said. "For that to happen that's probably impossible,” she said.

Settling on the price alone would be difficult enough. If the residents sell their apartments individually, values would vary dramatically with the size and state of the dwellings. Architectural historian Andrew Alpern said to reach an agreement, a developer would have to pay a premium over that market value for each apartment, which would be a very high price given that units have generally sold for at least several million dollars. It’s not so surprising, then, that offer after offer, first $32 million in 1981, and most recently $140 million in 2006, have all fallen through.

"Having a cooperative structure not financially under any pressure to sell” is one factor, Georgia Raysman, a current resident, said in a phone interview. “[But] that may have changed with the new prospect.” She was referring to the renewed developer interest in the neighborhood, including 425 Park, which is expected to break ground early next year and 432 Park, which is under construction and already taller than the Central Park trees.

Historically, Roth’s major contributions to Park Avenue were residential, but much of his firm’s subsequent work in the same area was a response to a different economic opportunity. In 1954, Emery Roth and Sons stripped the facade of the apartment house at 430 Park, just a block northwest of 417, and rebuilt an office structure around the steel frame. Since then, the interior and facade have been redone, resulting in the present sea green and glass frontage of the Boston Consulting Group. The Roth sons also designed the two glass towers immediately to the south at 400 and 410 Park Avenue, which now houses a Ferrari showroom on the ground floor.

Roth’s two sons, Julian and Richard, Sr., became partners in the firm in 1938 but did not share in the profits until their father died ten years later, historian Tom Shachtman said in his book Skyscraper Dreams: The Great Real Estate Dynasties of New York. As a result, the senior Roth’s grandson, named Emery II but known as Ted, said the family generally treated their lineage with a degree of ambivalence. “Like many families, there had been disputes, some from difficult financial times, that I was not privy to and that never healed,” he said in an email interview. However, architecture stayed in the family. Ted’s brother, Richard, Jr., led the firm from 1978 to 1993, a short time before the company closed. His son, Richard Lee, is also an architect and has designed for Donald Trump.

Accounts from relatives and historians indicate that relations between the Roth brothers were buisness-centered, especially as they had different social circles and contrasting but complementary interests. Older brother Julian focused on design and business affairs while the younger Richard, Sr., had studied architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. By the time of their father’s death, the two brothers, then both in their early 40s, had already shifted the firm’s focus to match the times. Rather than concentrate on apartment design, they built office structures that maximized the rental value of the properties they developed.

Alpern is very familiar with the firm’s work and has written a number of books on luxury apartment houses in New York City. Speaking of the Roth brothers in a phone interview, he said, “They could find ways of increasing something by a couple of inches in the curtain wall that would increase the number of square feet in the building. They built cheaply and it looked it.” To this comment, Richard, Jr., swiftly countered, also in an interview by phone, “The buildings weren’t cheap,” he said. “We were hired [because] we could do the best working drawings,” that left no loopholes for contractors.

Kahn and Jacobs, the architects of the current 425 Park, also worked on the Citigroup building two blocks south. (Evelyn Cheng)

The Roth sons worked with the same established developer families their father had worked with, such as the Rudins and the Uris family. Famous projects include the LOOK Building at 488 Madison Avenue, the Colgate-Palmolive Building at 300 Park Avenue, and the MetLife Building above Grand Central Terminal. When the LOOK Building became a landmark in 2010, the designation report prepared for the Landmarks Preservation Commission said it drew its design directly from the Universal Pictures Building at 445 Park, designed by Kahn and Jacobs. They were also the architects of 425 Park, which was built in 1957 with a similar stepped “wedding cake” structure that set the upper floors back from the edge to allow more sunlight to reach the street.

Tenants of 425 today include law and other private firms, as well as a Staples and a Duane Reade at street level. In contrast to the grim steel and glass of the current structure, the proposed sleek, white tower draws on international architectural trends. The prospect of more construction in the area does not seem to bother the residents of 417 very much as redevelopment has always been so much a part of midtown life.

One spring morning in 1981, fashion designer Cathy Hardwick -- whose protege was Tom Ford, formerly of Gucci -- looked out the window of her fifth floor apartment at 417 and saw a fire in one of the few remaining townhouses nearby.

"It burned down," she said. "A few years later they built a less attractive building. And they built more buildings, so soon all the windows were covered up and there was no sunlight."

When her son moved out of her apartment in the early 1990s, Hardwick sold it to Caroline Williams and relocated to a smaller unit in the same building. Her windows now look out onto Park Avenue, away from the proposed construction site, and she said she didn’t expect to be significantly inconvenienced. She wasn’t even sure about the exact development plans, as construction at 425 has yet to begin.

When developers L&L Holdings realized all the leases inside the current 425 Park building would expire in 2015, Raysman said, they saw an opportunity to rebuild the 1957 stone and dark glass monolith, a statement which a spokesperson for the developer confirmed. But this opportunity was encumbered by city zoning regulations that prevented demolition of the building, which would have maximized profits by allowing for a completely new structure.

To find the right architect, L&L Holdings held a design competition in 2012 among 11 firms, with the four finalists all from countries outside the United States. Later that year, they selected world-famous British architect Norman Foster of Foster + Partners, whose most significant New York work was constructing the Hearst Tower above the original six-storey structure from 1928 at 57th Street and Eighth Avenue, including preservation of its most important historic elements.

The reconstruction of 425 represents the first full-block development on this part of Park Avenue in half a century. The new structure will have high energy efficiency based on the regulations of the nationally recognized Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design, or LEED, program, the developers said in a press release. Although the occupants of the building will be completely corporate, there are plans for a civic art center on the ground floor. Foster’s design calls for a “landscaped terrace” and spacious interiors brightly lit from large glass windows and reflections off the white color scheme. In fact, the proposed designs for 425 helped create the impetus for rethinking the East Midtown area.

So did developer S.L. Green’s plans for One Vanderbilt Place near Grand Central Terminal, ten blocks to the south of 425. The firm had wanted a full-block, 65-story tower with 1.6 million square feet to replace the existing structure. But current zoning would only allow a tower 75 percent as large. Discussions with the city by both S.L. Green and 425 Park’s David Levinson contributed to the drafting of the failed East Midtown Rezoning Proposal of 2013.

From the start, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg was a strong proponent of the plan. Although Bloomberg had hinted at rezoning in January 2012, the Department of City Planning waited until almost the last minute in efforts to push the proposal through the City Council before Bloomberg’s third term ended. In the seven months, beginning in April 2013, that the city began a formal review of the rezoning plan, many groups from community boards to the city council discussed the plan in accordance with standard legal procedure.

In the end, it was a report from the City Club of New York that showed how under the rezoning plan the city would lose money by undercutting the market value of air rights in sales to developers. The council voted against the plan last November but local leaders, such as Councilman Dan Garodnick, whose jurisdiction includes East Midtown, said the city will reconsider the plan in the future, but under a less rushed timeframe.

The proposal sought to address several existing concerns over development and infrastructure in the district. As the majority of large office towers in the area were built before the stricter zoning laws came into effect in 1961, developers said the restrictions kept them from building larger, more profitable structures. Simultaneously, many major companies have started leaving their East Midtown location for newer office space in areas such as the revamped Financial district and the Hudson Yards project of West Midtown. The bulky and often awkwardly placed supporting interior columns, cramped layouts and lack of natural lighting made these once highly sought after towers much less desirable. As a great admirer of London’s modern skyscape, Bloomberg said rezoning East Midtown would allow New York to retain world-class status with competition now bearing down from Shanghai, London and other shiny metropolises.

Those who supported the dashed rezoning plan not only wanted to ease restrictions on new development but also to reduce the increasing strain on the Grand Central subway station. After the MTA reported 52 subway track deaths in 2012, many city officials began looking more closely at passenger flow on the green (4-5-6) train line at Grand Central Terminal, one of the busiest train platforms in the city. Engineers suggested small changes to the stairs and subway station layout to alleviate congestion, which, studies predict, will only get worse.

With rezoning, developers building near Grand Central Terminal would be obliged to contribute a small amount to the improvement of local transportation. Although the community board was most interested in these subway changes, critics pointed out that rezoning did not guarantee funds for transit. Rather, contributions would come too late for any proposed renovation timeframe and, more importantly, only two projects are even in the planning stage.

Regardless, construction at 425 is slated to begin next year. The developers will not be able to demolish as much of the old structure as they had hoped, but expect, by 2017, to have a new glass tower built. S.L. Green initially held off on plans for One Vanderbilt before beginning discussions with the city in April about an adapted design, Capital New York said.

Ellen Devens, an agent with Brown Harris Stevens who is selling a 417 Park unit, said the new projects will help the value of the the apartment building “positively.” While she said that more and more people have come to East Midtown to purchase and develop, even 10 years from now, “Park Avenue will always be Park Avenue.” Her prediction? “It will be more residential.”

The past occupants of 417 include a number of famous residents. William Friedkin, who won an academy award for best director in 1972 for his film The French Connection, had an apartment in the building from the mid-1970s until the early 1990s. Movie producer Martin Bregman, who produced “Serpico,” and his wife have lived in the building since the 1980s. Al Pacino sometimes visited, a former resident, Hjordis Gunnarsdottir, told me. She lived on the floor above. Gunnarsdottir and her husband, the then Icelandic ambassador Tomas A. Tomasson, moved into the building in 1978. Even though they returned to their native country in 1994, she said a representative from Iceland continued to live in the apartment until just a few years ago. The board at 417 was apparently more open to foreigners as she said the Norwegian Consul General also had an apartment for its representative on the fifth floor.

“I remember my husband telling me that when he was buying our place he had purchased a couple of apartments on Park Avenue before 417 Park, but the co-op board had turned down a foreign government and their diplomats,” she said in an email. “They didn't want them in their buildings. Diplomats were considered undesirable!! Go figure.”

Sarab Zavaleta and her husband, who worked at AT&T, lived at 417 with their three children from 1975 to 1985. She remembered several of the other residents of the time.

“There was one lady who translated the Babar books for children. Her [last] name was Haas,” she said in a phone interview. “I remember her name also -- h-a-a-s.”

Haas was the wife of Robert Haas, a Random House partner and co-founder of the Book-of-the-Month club. Her husband, who died in 1964, had asked her to translate the children’s picture books about the elephant family of Babar from the French original by Laurent de Brunhoff.

417 Park is haunted, the doormen say. Rubin Quinones, who has worked in the building since 2007, has always been impressed by the passion 417’s residents have for their building. That passion has seemingly translated into tales of ghosts who ride the elevators during the holidays up to the 11th floor, where no one lives because renovation is in progress. Legend has it that other unseen beings have nearly suffocated two night doormen by putting pressure on their chests. Quinones, who is 56, said one doorman could only free himself by crying out to God. He scraped his shoes against the foyer rug as he imitated the shuffling noises he hears in the basement when he’s alone. "Doors are closing when no one's down there," he said. Quinones is a retired New York City cop from Queens.

Famous decorators have designed the interiors of many of the apartments over the years. Mario Buatta included rooms from both of Hardwick’s apartments at 417 in his compilation of 50 years of work, published last fall. In the text, design historian Evans Eerdmans describes how Buatta hired premier faux painter Robert Jackson to paint the foyer floor to give it the appearance of marble.

Williams, who later bought Hardwick’s apartment, recognized the handiwork immediately when she was considering the purchase. She had looked at apartments in the building before a job relocation to Chicago. After she came back, she retired. “Then,” Williams said, “this apartment 417 came back on the market at a lower price than it had been a couple years earlier.” That was in 1995. Despite being on the east side of the building where there is less sunlight, Williams said she loved the location and the large, airy rooms, some with high ceilings.

“So a lot of the rooms were fancy, sponge-painted, the molding were all hand-painted by Robert Jackson,” she said. “So the location, the layout, and somewhat the way she'd done it, I was able to preserve those moldings. It was great.”

Zavaleta said a model who used to live one or two floors above her had an apartment designed by Adam Tihany, while another former resident, Peter Primont, had his apartment decorated by William Eubanks. But Eubanks left some of the existing work untouched. Just like Robert Jackson’s work in Hardwick’s apartment, the person who lived in the apartment before Primont had faux painter Pierre Finkelstein paint the library walls and bathroom molding to look like real wood and marble.

None of this elaborate work is a surprise to Williams. "If you're going to spend the money, might as well go all out," she said.

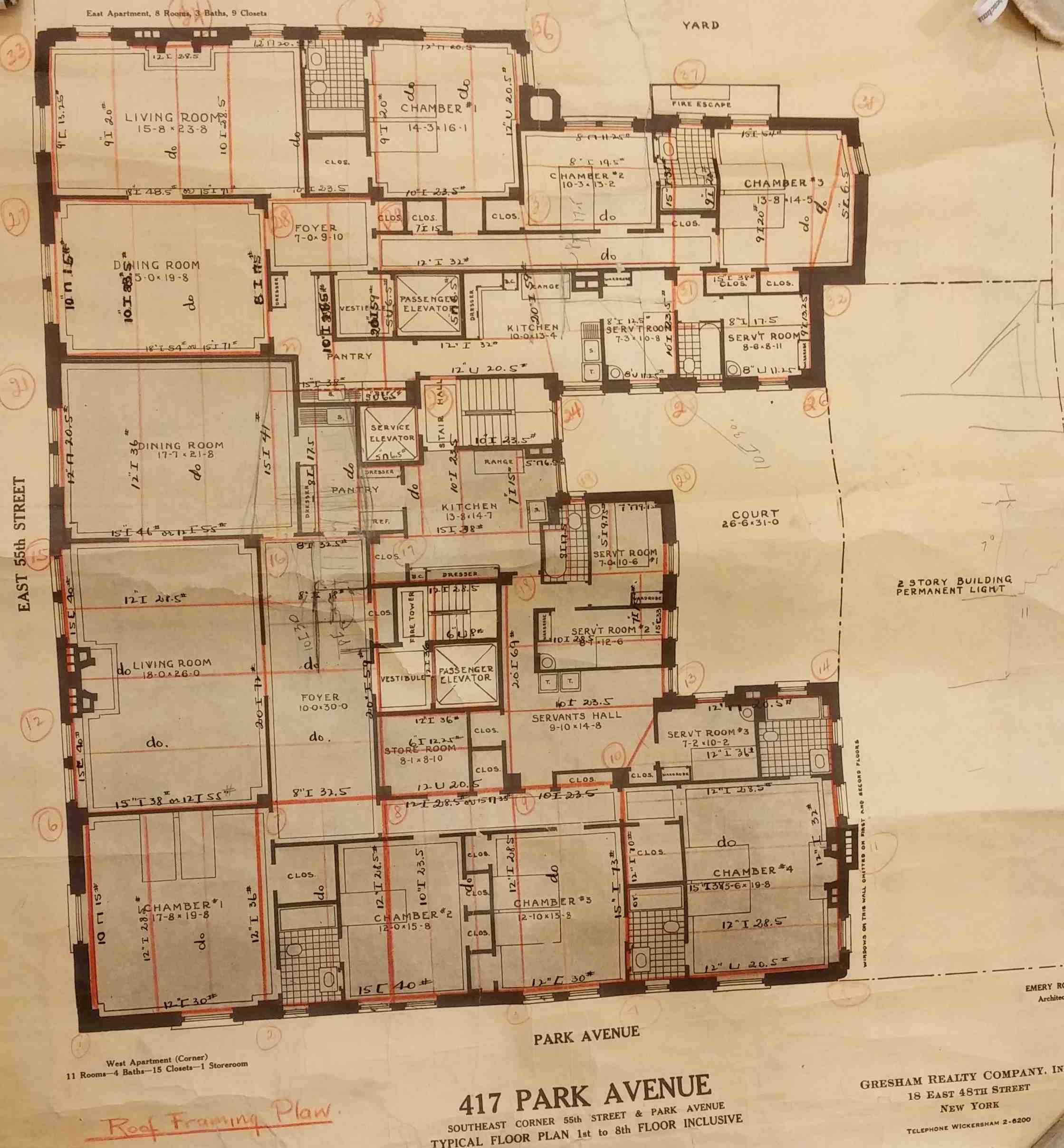

Yet many elements of the apartment remain just as Roth originally designed them, particularly the floorplan and discreet elevator entrance. Although critics say 417’s low-key exterior is not representative of Roth’s generally more ornate work, the interiors contain many features common to his designs. Alpern, the architectual historian, wrote in an article about the building that the skillfully laid out rooms offered well-framed views from the entrance foyers of fireplaces, windows, or other architectural features at the right angles.

This plan of the first to eight floors shows how a separate apartment bank serves each apartment on every floor. (Avery Library, Columbia University)

The apartments Roth built are all spacious, with large kitchens and several bedrooms. His signature accomplishments were introducing a centrally located foyer and adding a private service elevator for deliveries in many of his luxury apartment houses. He was able to convince developers to spend money and put fewer but better designed apartments into his buildings, “a skill not all architects have,” Alpern said. He added that the work that Roth put into creating quality living spaces makes the apartments more valuable now than similar ones designed by his contemporaries.

“417 as it was originally laid out was very, very good,” Alpern said. “I like it, it was an elegantly restrained building from the outside, and finally a few years ago, they cleaned it.”

Even with the splitting of the 16-room top floor apartments, no unit in the building is smaller than 2,800 square feet, Dusovic said, with some apartments as large as 4,000 sq. ft. In 2010, one apartment sold for $7.7 million.

With her west-facing apartment, Zavaleta had grand views. “The apartment was 4,000 square feet. It was enormous. My kids would skate in there and bicycle in there--it was so big,” she said. “I grew up in India and we lived in big homes. And my ex-husband was South American. I was very comfortable. I loved it. It was very nice, a very well-maintained building. It was expensive at that time, but after we left it multiplied, like doubled in value, and therefore now maintenances are now very high. I regret having given up that but my husband was strong and insistent and I couldn't fight him on that.”

The building developers, Bing and Bing, also ensured that the upper-floor apartments had permanent light on the south side by purchasing the two-story carriage house next door with a garage on the first floor and living quarters above. Servants or guests would stay there, Dusovic said, until the 1940s, when the short building was sold and businesses took over.

“It actually was a TGI Fridays when I moved in,” former resident Peter Primont told me when we met. Now the building, 410 Park, houses high-end Italian clothes retailer Stefano Ricci. Before the TGI Fridays, Alpern said, “it had a whole succession of businesses. . . . The facade has been redone a couple times.” The first floor of 417 Park has also featured retail space since at least 1933. Formerly Barra of Italy, the store is now home to the shoe line of Walter Steiger. A dentist also has an office on the side of the building. As the board prohibits leases, Dusovic said these business operators actually own the office space. “They own it for investment,” he said.

Emery Roth designed 417 Park before his most of his better known work in the late 1920s along Central Park. (Evelyn Cheng)

Despite its history and legacy design, 417 Park has not been landmarked. Other Roth buildings, from the Ritz Tower to the LOOK Building, have received the designation by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. When activists heard about the potential increased development of the East Midtown Rezoning proposal, the Historic Districts Council put 417 on a list of 78 significant buildings threatened by the plan. Discussion with the landmarks commission narrowed the final list to 31 structures, including 417 Park and four of the 12 other existing Roth-designed structures between 46th and 57th Street. The Universal Pictures Building is also on the roster. But little action has been taken to formalize an official status for any of these buildings.

“Obviously it doesn't need to be landmarked because it's a co-op and the people who live there [have no interest in selling 417],” Alpern said. “Theoretically it should be landmarked so that some board isn't going to replace the windows with single-pane windows, [or] put a different top on the cornice. The board could do this if they were crazy enough to do that.”

The apartment building does adhere to some historicizing guidelines, such as making sure the light fixtures, facade and lobby interior remain as close as possible to the original. Some residents, Dusovic said, have even retained the 1920s intercom units inside their apartments. While most have renovated the interiors of their apartments, their respect for the building itself is evident in even the most casual of conversations. Its elegant design and spacious layout make it stand out among the more austere buildings around it.

“It's a refuge in midtown,” said Raysman, who lives on the second floor, “which is why I think we would be very sad. I'm not saying we wouldn't want to [sell, if there were a great offer]. It would not be something we would do with a happy heart.”

Former residents also maintain an affinity for the building. Williams said that after she finishes spending much of her time on the horse-riding circuit, which has brought her to live in the countryside, she would like to move back to 417 Park.

Primont said he spent about six years in a post-war, white brick apartment building across from the Frick Museum on East 70th Street. “It was a very nice apartment and the building was a very nice building, but it was just plain,” he said. “You wouldn't walk in and go ‘Wow,’ whereas this apartment you would walk in and go ‘Wow,’ just like if you walk into the lobby at 417 Park, you would say, ‘Wow.’”

Even with discussion of rezoning returning to the City Council later this year or next, the likelihood is that 417 will retain its current status and perhaps influence the nascent trend back to more residential life in East Midtown. In the last year, both UBS and Citigroup announced plans to vacate most if not all of their Park Avenue offices, located at 49th and 54th Streets, respectively. Up at 56th Street, a live videocam tracks the progress of 432 Park, where the 92nd floor penthouse lists for $79.5 million.

Rubin Quinones, on the left, and Javier Briones guard the entrance to 417 Park. (Evelyn Cheng)

On 55th Street east of Park Avenue, orange signs warn of delays from the construction of the East Side Access transit line further down the block. But 417 stands serenely, its limestone facade still a dirty grey despite a cleaning in 2006. Few pass in or out, but the doormen are there, guarding the “holdout house,” as historians put it.

“417 Park doesn't shout,” Alpern said, “417 whispers.”