Living with an Autoimmune Disease

“I almost never hear my neighbors and often wonder if anyone else lives around me,” writes Madeline Murphy, 43. “There are hundreds of condos but no people.” Murphy lives with her husband Ken, but her days are spent alone. She doesn’t hear a dog bark. She doesn’t hear the birds chirp. She has lived in Centennial, Colorado for the past year, but her knowledge of the town has not changed since the day she moved in. She can tell you the best way to get to the nearest hospital and she can recommend a good doctor -- or at least one who will listen. Murphy, however, is not purposefully avoiding the world.

“I usually feel sick every morning, if you can imagine waking up and feeling sick every day,” she says, looking down. “It’s terrible and it makes it hard to get started.”

Murphy says this in an achingly slow manner. She lifts her head, but her shoulders sink. It’s the ordinariness of her face that is most striking. Her hair is mostly straight and falls down to just below her shoulders. The color is a washed-out chocolate brown. She wears modified-oval black-rimmed glasses. Her eyes are a dark coffee color, and on a good day they don’t reveal her age. But most days are not good days for Murphy. She was diagnosed with Addison’s disease in 2010.

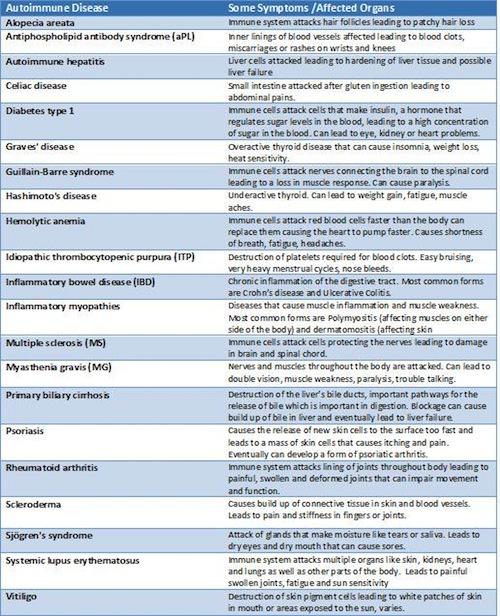

Addison’s disease is only one of the over 100 different types of autoimmune diseases recognized by the National Institute of Health. In the early 20th century Nobel Prize winner Paul Ehrlich first described them as “ horror autotoxicus .” But even this seems a demure term for such unsettling diseases. The immune cells that usually act to destroy the bacteria and viruses in the body go offline, and are reprogrammed to launch an immune attack on the body. The concept remains perplexing even to the medical community, who belatedly recognized autoimmunity as a disease category in the 1950s.

Yet according to a January 2012 study by the National Institute of Health over 32 million Americans have tested positive for auto-antibodies: a characteristic sign of autoimmunity. The auto-antibody is a protein released by immune cells which can initiate an attack on the body cells. The presence of such proteins is determined, in part, through an anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test which only requires a blood sample from the patient.

Information from Womenshealth.gov

Murphy visited endocrinologists, a type of doctor that specializes in treating hormone mediated diseases, and some of San Francisco’s best diagnosticians to identify the cause of her immunological problems. In 2007 she complained of general body pain and fatigue and by 2009 these symptoms became debilitating. Murphy forgot to get off the bus at the right stop on her way to work. She felt confused throughout the day. She was forced to take sick days, and soon started to feel alienated from her coworkers.

Eventually a new endocrinologist thought the symptoms could be the result of a dysfunctional pituitary gland, so Murphy underwent an insulin tolerance test in which her blood glucose levels were reduced to dangerously low levels so doctors could test for hormonal changes in her blood. But it wasn’t the pituitary that was failing; it was Murphy’s adrenal gland, a bodily structure responsible for the “fight or flight” response during stress. Within days, Murphy’s doctor knew that she suffered from Addison’s disease .

Beth Webber, 49, was not as lucky as Murphy.

“My first hospitalization was in 1996 in Aspen and they thought that I drank too much water,” says Webber. She explains that during these crises her blood pressure dropped to 60/40 mmHg, she fainted, her electrolytes fell to dangerously low levels, and without medical attention she was just moments away from slipping into a coma. And with no diagnosis, there was no treatment.

Webber could do nothing to anticipate these attacks. In an attempt to carry on with her life, she ignored the symptoms. “After four or five years I was getting sick all the time,” says Webber. But working in international finance on Wall Street did not leave room for sick leave. Her colleagues pushed forward without her. “I didn’t plan on retiring at the age of 39,” says Webber. She didn’t have a choice; she couldn’t function at work any longer. Her only hope was that Unum, her disability insurance company, paid her claim. Without it, she would have to cover her medical and living expenses alone.

“Even though I did have a policy, they disputed the claim. I had reputable doctors from numerous hospitals and fields of medicine confirming and supporting my leave,” Webber says, discussing the trouble she went through to get disability coverage. “But I didn’t get it simply because I didn’t have a diagnosis,” says Webber. Until she could return to work, she relied on her personal savings.

Despite going to the best medical professionals, Webber watched the years pass with no results. One doctor suggested she try the anti-malarial drug Plaquenil that seemed to be working in autoimmune patients in Europe, but he couldn’t provide her with any specific diagnosis. So with encouragement from her mother, Webber decided not to take the drugs. “I guess I thought it would go away,” she says.

But it didn’t. The Mayo Clinic told her she may have something autoimmune related, but she would have to return in a few years so her symptoms could point doctors in a more precise direction. “I didn’t go because I was in denial I guess. As long as I was able to go to work and kind of balance my life, it wasn’t that invasive,” says Webber.

Some days Webber pretended she wasn’t tired; that her pain was manageable. She got up from bed, walked to the kitchen, fixed breakfast and went to work. But then, unexpectedly, pain invaded every inch of her body. How intense and how long it remained was unpredictable. Crawling replaced walking. Praying replaced thinking. Her days were spent lying in bed or on her couch like a corpse, hands crossed over her chest. Even now Webber has to prepare herself before speaking of the pain she used to endure every day. Her only protection from the fear of what tomorrow may bring is the suppression of the past.

“I was only diagnosed a year ago, sweetie,” says Webber, “Only a year ago.” Oddly enough, it came after a routine check-up for a colonoscopy. The procedure requires the patient to have a completely clear colon. For 24 hours before the exam patients cannot eat solid foods, significantly diminishing the amount of electrolytes readily available. Webber’s doctor worried that she would fall into a coma, or die, on the examination table. So he referred her to Dr. Noel Maclaren, a pediatric endocrinologist and medical researcher who opened the BioSeek Endocrinology Clinic eight years ago. Dr. Maclaren helped develop tests for Addison’s disease and Type 1 Diabetes , the autoimmune form of diabetes. After 14 years of searching for a diagnosis, there was finally the perfect doctor-patient match.

“You know what, I am not going to let you do this colonoscopy until this blood test comes back and they are going to be pretty specific. It’ll take about two or three weeks,” Dr. Maclaren told Webber.

“Believe me, you are not going to figure it out. People haven’t figured out for a decade. It’s just my life. You know, it is what it is,” said Webber.

“No, no, I really think I know what you have,” Maclaren said.

“Yeah, right. You and the other 35 doctors I have seen.”

So she waited. After 14 years, a few weeks seemed quick. And as Webber remembers the episode, she can’t help but smile.

“He asked me to come in,” Webber says recalling a long ago Friday.

“I have an appointment with you on Tuesday,” Webber remembers saying, “so I will see you Tuesday, Dr. Maclaren. Thanks.”

“No, Webber I want you to come into my office today,” he said.

Webber parried. “I am going away for the weekend and I don’t have so many weekends where I feel so well.”

“No, it’s really important. I’m going to stay in my office until 8:00 p.m. tonight, and you have to come in.”

Reluctantly, Webber agreed.

When he presented Webber with her diagnosis – Addison’s disease – Dr. Maclaren had tears in his eyes, Webber remembers. His tears weren’t for the diagnosis, Webber believes, but for the 14 years she’d suffered. That Friday, Webber finally understood what was going on inside of her. The pain she felt was real and it had a treatment. Webber could start leading a somewhat normal life.

Luckily, most patients are more like Murphy than Webber, and only wait three to five years for a diagnosis. However, once there is a diagnosis for one disease, often more follow.

Murphy knew from the start that her health issues were not only related to the Addison’s. There was a continuous pain in her leg that she couldn’t explain. But her disappointment with doctors was leading her down a self destructive path. “I actually delayed going to a doctor because of my leg pain. I thought, oh what are they going to do? They are going to say it’s just me again, being in pain. It’s just me complaining. I delayed it several days until I couldn’t stand it anymore,” says Murphy. But the pain was real and the throbbing in her leg came from a blood clot. She explains, “I didn’t get the help sooner because I didn’t think anybody was going to believe me.”

Most autoimmune diseases are like a match that, once lit, can ignite into multiple diseases. Autoimmune attacks lead to an accumulation of immune cells that cause inflammation. As the population of these cells increase, so does the chance that they will impact other parts of the body. The immune cells that attack the skin of a psoriasis patient can migrate to attack joint cells, leading to what is known as psoriatic arthritis. Eventually, the range of symptoms becomes so varied that disbelief is natural. Patients that complain about five or six aches are quickly dismissed for exaggerating.

At the age of 23, Virginia Ladd, the founder and president of the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA) , was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) , an autoimmune disease that attacks multiple organs in the body. As a representative of her organization, Ladd speaks with autoimmune patients across the United States. Many patients, she says, are concerned that they are not getting the best treatments. “If you have a systemic autoimmune disease, you may have joint pain one day. You may have a rash the next day. The next week you may have a pleurisy,” Ladd explains. “With a host of symptoms, it’s difficult to know which doctor to visit.”

Rheumatology is a specialty within medicine that deals closely with autoimmune patients. Originally, rheumatology was dedicated to the treatment of joint and musculoskeletal problems. As the number of patients diagnosed with autoimmune diseases grows, this medical specialty has become overwhelmed and the evolution of the autoimmune rheumatologist into an autoimmunologist seems natural. Just as there are oncologists for cancer patients and cardiologists for heart disease patients, autoimmune patients may need a physician dedicated solely to the care of autoimmune disorders.

“As a person with lupus, I had to see a rheumatologist, nephrologist and dermatologist,

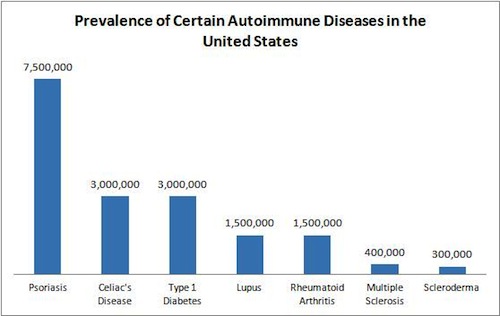

Ladd says. By starting the AARDA, she hoped to unite all autoimmune diseases into one category. “Many of the autoimmune diseases would be rare if you only look at a single disease, but when you look at them collectively they are right there with heart disease and twice as prevalent as cancer,” she says.

Arguably, mastering the full range of symptoms in autoimmune diseases is a difficult task for even the most accomplished physicians. The disease can affect one organ or multiple organs. Symptoms can be debilitating one day and gone the next. But the underlying etiology and treatments of autoimmune diseases are all similar. And though eventually patients generally do get the proper care, they can waste years of their life seeking the right diagnosis. The development of the autoimmunologist may provide a step towards improved patient care.

Mounting evidence also shows the need to further investigate the way patient and family history can predispose an individual to specific diseases. There is a strong genetic component, for example, in the autoimmune disease of psoriasis. Researchers are now aiming to identify which specific genes could cause the development of these diseases. If patients know they are likely to develop an autoimmune condition, they can inform their doctors and get a faster diagnosis.

“I felt that these diseases run in families and there had to be some genetic connection because of what I saw in my own family,” says Ladd. “We now know that they do run in families. There is a genetic component, but it is not enough.” Studies show that there is only a 15 to 57 percent chance that one identical twin will have the same autoimmune disease as his or her twin, depending on the disease. If autoimmunity was purely genetically linked both identical twins would have the same disease. Instead, there is likely a secondary trigger.

Current research focuses on discovering these secondary triggers. There is growing belief that the discovery of secondary triggers could lead to the discovery of how autoimmunity develops. Books like Donna Jackson Nakazawa’s, “The Autoimmune Epidemic,” describe the development of autoimmune diseases in neighborhoods where toxic chemicals leaked into the soil. There is evidence that connects silica exposure to the development of Rheumatoid Arthritis(RA) and Scleroderma , an autoimmune disease affecting connective tissue. But even viruses, bacteria and stress have been named as potential triggers for autoimmunity.

As knowledge of autoimmune disorders grows, scientific terminology has evolved as well. Today, definitions are better shaped to the evolving nature of the disease. For example, the disease defined in 1968 as multiple autoimmune syndrome (MAS), is now referred to as polyautoimmunity. The new term reflects the way autoimmunity propagates itself: that once the condition’s self-attack mechanism is initiated, there may be no way to stop it.

If there is one person who understands this, it’s Webber. She was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis , an autoimmune disease that attacks the thyroid gland. The thyroid is responsible for releasing hormones that control metabolism. In Hashimoto’s patients the malfunctioning thyroid leads to weight gain, hair loss, fatigue and depression. Fortunately, the disease can be treated with daily hormone pills.

The cluster of diseases that threatens Webber today was foreshadowed by a childhood illness. Raynaud’s phenomenon is an early indicator that an individual may be susceptible to developing an autoimmune disease. In mild cases, a Raynaud’s flare results in white, blue or red colored fingertips or toes as a result of irregular constrictions of blood vessels in response to temperature or other stresses.

For some, the vessel constriction completely blocks blood flow and leads to the formation of ulcers. Maria Vrakas, 33, still carries the scars of her Raynaud’s flares. “I couldn’t even pick up a cup,” she says. But Raynaud’s is a condition that modern medicine can effectively treat. Vrakas doesn’t have to worry about the consequences of ordering her crème brûlée latte or of answering her phone.

Vrakas always wanted to be a kindergarten teacher. She loved children and wanted to make a difference in other people’s lives. After graduating college, she was excited to finally spend time as a teacher’s assistant. But then she started getting sick. If a boy came in with a cold, Vrakas was sure to catch it. The only difference was Vrakas’s cold could last weeks. “Every time I try to work full time I get sick,” Vrakas says, “and I mean in-the-hospital sick.” For Vrakas, the thing standing between her and her dream job was not willpower, intelligence, or education: it was her immune system.

In 1998, Vrakas was diagnosed with SLE. “I had heard of lupus before my diagnosis,” she says. “The sister of a Backstreet Boy died of lupus at the age of 37.” At the time of her diagnosis, autoimmune disorders were still relatively obscure. Most of the information on autoimmune diseases were published in medical journals, the AARDA was only seven years old, and the S.L.E. Lupus Foundation was just slowly gaining recognition. But without a doctor who spent time researching autoimmunity, it was difficult to recognize the signs and symptoms of SLE.

Vrakas’s lack of knowledge on the subject manifested itself as denial. “I didn’t treat myself as if I didn’t have an illness,” she says, “but I didn’t take it as seriously as I should have.” A lupus diagnosis, like that of other autoimmune diseases, runs the course of a patient’s life. At any moment there is an immune cell ready to attack the body. During periods remission, however, this is easy to forget.

Vrakas was tired of taking prednisone, the corticosteroid treatment often given to lupus patients. The medication caused Vrakas to grow facial hair. She developed “moon face,” a common side effect to prednisone that literally causes patients faces to swell into the shape of a full moon. Though not physically painful, the side effects slowly gnawed away at Vrakas’s self esteem. She started wondering if the treatments were worthwhile. Maybe the lupus pain wasn’t so bad. Maybe she didn’t need the Prednisone, she thought. The fatigue, swelling and muscle stiffness might be gone if Vrakas stopped her treatments.

This scenario is one that Dr. Jill Buyon, a professor at the New York University School of Medicine, has seen many times. She explains that lupus patients do not have many treatment options. Most of the drugs cause irreversible side effects like sterility and osteoporosis. Though Dr. Buyon has dedicated her career to improving treatment options for lupus patients, the lack of new treatments accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) leaves her disheartened, she says. Many of her patients complain about the difficulty of living with the acne, the weight gain and the mood changes associated with Prednisone, she adds.

“One of the worst experiences I have ever had with lupus was at Albert Einstein,” Dr. Buyon recalls. “A woman literally said, ‘I would rather die than take the steroids.’ And she died.”

The distaste for medications is not rare in the world of medicine. For autoimmune patients, however, there’s no room for error. Even a short break from one medication can put a person with an autoimmune disorder in the hospital. Vrakas was not the exception; she was forced to go to the emergency room within a week of stopping her own medication. Her gastrointestinal system was so ravaged by rogue immune cells that she was forced to take her medications intravenously. Though she tried retaking her medication orally before going to the hospital, anything she swallowed came up moments later. Worried, her doctor decided to do a full workup, which included frequent urine samples.

“He discovered all these new things going on inside of me,” Vrakas recalls. The memory brings tears to her eyes. She explains that her kidneys were not functioning properly. She was told that her only option was chemotherapy.

“I remember going to do the chemo and sitting in what was basically a circle of people doing different types of chemotherapy,” Vrakas says, “You think, there are so many people out there who are dealing with worse issues. You wake up with pains and you want to complain. But then you think about what other people are going through and you can’t.”

In autoimmune patients, aberrant immune cells slowly develop an attack that wears down the barriers that protect the tissues and organs in the body. Unlike viruses or bacteria, these immune cells are more like guerrilla soldiers waiting for the opportune moment to reveal themselves than foreign armies. They are ever-present and remarkably well hidden. It may be the subtlety of the autoimmune attack that is so perplexing. For patients this means understanding that their pain is not visible to the rest of the world. It is something that they must accept as a part of their own lives. Webber says, “So I have autoimmune stuff. But you don’t talk about it. It’s sort of like, ‘Oh, I have my period.’ I’m not going to talk about it. I just have it.”

There is an understanding in the autoimmune community that most healthy people don’t know, or care to know, about the difficulty of life with an autoimmune disease. Unless someone has spent days feeling like a walk down the street is too strenuous, or prayed that the food they just ate won’t cause excruciating abdominal cramps, they can’t relate. But patients like Maria don’t want pity and they don’t want to be treated differently. They just want people to understand the difficulties of living with an autoimmune disease.

Collection of Data From Different Organizations

Anne Sikora is a licensed clinical social worker in New York City. She was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS) , an autoimmune disease that attacks the cells protecting nerves in the brain, 12 years ago. She explains, “I was very concerned initially about sharing professionally that I was going through this hard time. I was worried people wouldn’t refer patients to me.”

Sikora has a mild form of MS that allows her to remain very active. She has a successful career as a therapist and is currently studying to get a doctorate in psychology. She also spends much of her time taking care of her children. Though she was diagnosed after giving birth to her first child, Sikora did not feel comfortable sharing her diagnosis. “My kids have not known all this time that I’ve had MS. I told them recently because my son is 12 now,” says Sikora. And until she had her symptoms under control Sikora explains, “I never wanted to worry them.”

The comfort that comes from everyone thinking you are healthy is that eventually you can convince yourself that it is true. As long as your body cooperates for a while, the slight aches and pains resemble the daily problems that all healthy people suffer from. Sikora says, “I’m in healthy denial.” And there is a benefit to this kind of thinking. When faced with a life-long illness, denial is a form of hope.

But most autoimmune patients cannot survive on healthy denial. Instead patients are confronted with the reality that they are not getting better. There is something inexplicable occurring in their body. When Webber was first getting sick she explains:

“I was getting skinnier and the doctors didn’t know what was going on. My girlfriend came over and her eyes welled up with tears. When she hugged me she said, ‘Do you think you are going to die?’ And she’s the kindest, sweetest person. I couldn’t believe she’d actually ask me that. And I was like, ‘Well I don’t know. But I know that nobody knows what’s going on.’ And that was the hardest part, nobody knew.”

Though Webber’s pain comes mainly in sporadic crises, many autoimmune patients gradually develop their symptoms. The attack is mounted so slowly that patients are not aware of the slight changes in their body.

Sikora expected some difficulties maintaining her career and taking care of an infant. But she thought her active lifestyle had prepared her for a baby. As time passed, she quickly realized that something was not right. “I would see the other moms around me getting through the day with their kids, and I thought, ‘Oh my god, I am having such a hard time waking up a bunch of times at night and making it through the morning until naptime.’ I was just super tired. Really, really exhausted,” says Sikora. She explains that her great-uncle had MS and that her mother thought Sikora might be suffering from a similar disease. Still, Sikora did not feel comfortable going to a doctor for something as simple as fatigue.

Eventually Sikora lost vision in her right eye. The vision loss was a result of inflammation of the optic nerve, and is a common symptom in MS patients. The duration and severity, though, varies from patient to patient. Sikora explains, “I went in to the eye doctor and I couldn’t read the big E. The ophthalmologist said to me, ‘You know, you should really get this followed up on. Either you have a brain tumor or MS.’”

Sikora was then referred to a neurologist who could give her a more specific diagnosis. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results of Sikora’s brain showed clear MS lesions. Through the combined efforts of her ophthalmologist and neurologist, Sikora was lucky to get a quick diagnosis, and with the proper treatment her vision returned.

But MS is one of the most well known autoimmune diseases and affects approximately 400,000 Americans. Rare autoimmune diseases require many different specialists before a diagnosis is made. Though there are cancer centers that provide cancer patients with care from multiple oncologists and other medical specialists, there are no general autoimmune centers. Currently there are only disease-specific centers and research-based autoimmune centers. For patients whose symptoms vary from day to day, an in-patient clinic uniting different specialists could be one of the few solutions to a faster diagnosis and more comprehensive treatment plan.

The changing symptoms of autoimmune diseases leave patients anxious at the start of every day. Rheumatoid arthritis is often worse in the mornings while diseases like Myasthenia Gravis , an autoimmune disease that attacks nerve cells that control muscles, gets progressively worse throughout the day. Other autoimmune diseases vary in symptoms and pain levels from one day to the next. Yesterday’s pain could be the onset of a month long incessant autoimmune attack, but it could also mark the end of a flare.

It is the unpredictable nature of these diseases that often worries autoimmune patients. “It’s sort of like you’re walking on thin ice,” Webber says. “You feel like you never know when the attack is going to come.” She copes with this reality by avoiding making any plans for weeks at a time. “You just feel so stupid canceling,” says Webber. Despite close monitoring of her medications throughout the day, Webber knows that at any moment her symptoms can return. She may only need a few hours of rest or she may need a few days.

While some patients find the appropriate balance of medications that allow them to function almost normally throughout the day, others struggle to find a combination that manages their pain effectively. Murphy is on a constant search for the newest medication. With each new therapy, Murphy’s hope for a stable life grows.

In the winter of 2012, Murphy began a new treatment plan recommended by her immunologist. The treatment required her to remain in a bed for five hours while syringes containing a blood product were slowly pumped into her body. Though she describes the procedure as invasive, Murphy once again had hope. “There were a few days where I thought something was working,” Webber says. “I think it was four or five days, I felt almost normal and it was the best feeling in the world. You know, just to feel normal.”

Murphy compares the feeling to getting over the flu. She explains that, at first, “it seems like, ‘Oh god, how are you going to live through it?’ But then, you know, you do. And it’s like a new world when you get over the flu. The sun is shining and everything looks good and smells good.”

But Murphy’s illness is not the flu, and her respite was fleeting. Unlike people with properly functioning immune systems, Murphy is constantly in pain. She is constantly tired. She is constantly wondering why she suffers so much, why she can’t always be active, why she can’t always go outside.

Relationships often suffer after a patient is diagnosed with an autoimmune disease. The concern of the next disease flare causes stress for not only the patient, but for their loved ones as well. With each flare, the balance in the relationship shifts. Webber explains that at first it is nice to have someone around to help and take care of you, but as the illness lasts the gratitude becomes almost overbearing. “It changes the nature of the relationship from romantic to parental,” says Webber.

Patients with a chronic illness often have to make many changes to their daily routine. They learn to adapt their schedules to their fluctuating health. Sikora explains that these changes become the stressors that accumulate over time. “I just went through a separation with my husband of 20 years,” Sikora says. She explains that after her MS diagnosis she started going to bed early, around 9 p.m. While her second child was an infant, Sikora stayed at hotels during the night. She knew that without the appropriate amount of sleep, she could not function the next day. Sikora says that she isn’t sure her ex-husband would agree, but she imagines that her illness played an important role. “I think that it was hard on him. I think that he probably picked up a lot of slack and felt like he had to be stoic about it. But it took a toll on him,” says Sikora.

There is a common feeling in the autoimmune community that the chronically ill are burdens on their partners. The physical inabilities of patients make them feel incapable of doing anything for anyone but themselves. This comes from the belief that patients have to “jump over hurdles” to accomplish things, Ladd explains. But having lived with SLE throughout her life, Ladd has learned that, “No you don’t always have to jump over it. Sometimes you can crawl under it without anyone knowing you didn’t jump over it. You find a way.” Patients may not feel well every day, but taking advantage of the healthy days is enough to remove some of the guilt patients feel towards their loved ones. Ladd says, “My husband was a sucker for home baked cookies. I’d feel so tired, but I would slice them up so they’d be just done when he walked in. It’s hard to be upset when somebody just made you a batch of fresh chocolate chip cookies.”

Murphy’s expression changes when she speaks of helping her husband when her Addison’s is least active. She smiles and her tone becomes softer. For a moment, she is no longer the inconvenience in the relationship, she is the provider. “I cooked for my husband, which I really wanted to do for him because he mostly does the cooking, and everything. I felt like I could contribute again,” says Murphy.

One of the most demoralizing aspects of autoimmune diseases to patients is the inability to help loved ones who devote endless hours to their care. There is an insurmountable debt that piles up and creates an odd logic. Ladd relied on the support of her husband while they raised their three children. She remembers the embarrassment of hiring a maid to clean the house when her lupus was most active. But she also remembers the one time she contributed more to the relationship, “When my husband had a heart attack once, in this very twisted way, I was almost happy because I could take care of him for a change. And it felt good because he had always been so good to me.”

Whether it is a spouse, family member, doctor or hired nurse, autoimmune patients rely heavily on help from others. It could be for carrying grocery bags on days when a rheumatoid flare leaves a patient incapable of grasping anything. But for some people, it could also be to help feed or care for them at home.

“I had 24/7 help because I couldn’t do anything,” says Webber of the times her Addison’s would flare up:

“People would feed me and I remember looking at the bottom of the spoon. I said, when I get better I am going to write a poem about the drip from the spoon. I know every time somebody feeds me it’s going to drip down my chin, down my neck and onto my chest. You can’t say anything because there are just so many things you can ask people to do for you.”

For someone like Webber, who considers herself a type A personality, the help, though appreciated, weighed on her self-esteem. She was an athletic woman, successful in finance, and a world traveler before her diagnosis. But with a flare up of Addison’s her world changed.

Though over 75 percent of autoimmune patients are women, men also suffer from the effects of autoimmune diseases. Marc, 57, was only 17 years old when he first developed Raynaud’s symptoms. But his symptoms progressively worsened until doctors diagnosed him with scleroderma, 20 years later. Marc suffered from a specific subtype of Scleroderma known as CREST syndrome, each letter representing a specific physical condition associated with the disease.

In the summer of 2009 and spring of 2011, Marc had surgery on each of his middle fingers to remove calcium-deposits that formed underneath his skin. He explains that the deposit in his finger, which resembled a stone, was one of the most painful symptoms of his scleroderma. He says, “If I accidentally touched anything it was the most painful experience that I could describe. I mean, it would knock the breath out of me. I would see stars.” For over a year Marc avoided simple tasks like typing on a computer or buttoning shirts. But now, he can’t even feel picking up a penny because of the scar tissue in his fingers.

Marc explains that one of the most difficult parts of having scleroderma is its invisibility to the outside world. He is lucky to have only small red spots on his face that are a result of dilated capillaries, but his Raynaud’s is so severe that even air conditioning makes him uncomfortable. He wears special gloves with the fingertips cut out to work in his office and is always careful to travel with clothes to keep him warm. He explains that his hands quickly turn white in the cold. He says, “I complain about it. My friends say, ‘Why are you complaining about it? It’s cold. Big deal. Put a sweater on.’ But they don’t know what it does to you in that internal mirror. It’s not just a feeling of self-consciousness but actual pain.”

Yet Marc admits that he is still in denial about his disease. He says that he is more open about telling people about his diagnosis, though he explains that “in business they see it as a weakness.” He is part of the Board of Directors of the Scleroderma Foundation Tri-State Chapter . He wants to spread awareness about scleroderma and call attention to a disease that is physically painful and emotionally distressing. He admits, however, that out of embarrassment he has never told his children, aged 21 and 27, directly about his diagnosis.

Marc does not take any medications directly related to his scleroderma. He says he’s tried some, but none of the treatments seemed to improve his symptoms. Until he develops Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH), one of the main causes of death in scleroderma patients, Marc is not eligible for any novel drugs currently in clinical trial. Instead he focuses on avoiding the triggers – like cold environments -- that cause him the most pain.

But other patients, like Sikora, find that their medications replace their symptoms with a new pain. Sikora was first treated with the drug Copaxone, a commonly used MS medication. The drug modulates the immune attack on the myelin sheath cells that protect the nerves, though the exact method through which it functions is not yet understood. Most MS patients take the drug to slow the progression of their disease and decrease the severity of their symptoms. For some, the daily injections cause more discomfort than protection.

Sikora explains, “You give yourself the shot and you get the flu.” Like most autoimmune disease medications, the drug decreases the overall strength of the immune system. Since it is difficult to isolate self-attacking immune cells, these drugs non-selectively slow down all immune cells in their ability to attack healthy or diseased tissue. But this not only leaves patients more vulnerable to other infections, it can also lead to uncontrollable side effects.

“It made me depressed,” says Sikora. Every morning after taking her Copaxone injection, Sikora woke up crying though she says she “is not a naturally depressed person.”

Sikora suffers from a less debilitating form of MS that allowed her to consider other treatment options. She explains that, “everyone has a different story and a different way they are working through life with their disease.” She dismissed support groups because she was too scared to see patients with a more progressed, severe form of MS. Instead, Sikora decided to try a new type of therapy at Mount Kisco Medical Group , a clinical affilitate of Massachusetts General Hospital. Doctors at the clinic proposed that Sikora try intravenous vitamin therapies.

“When I initially started going to that clinic I could barely make it from the train station up to the clinic, you know it was a hard trek of eight blocks. But after I had maybe two or three treatments I was bouncing up the street,” says Sikora, “It just felt like it was right.”

She decided to add Chelation therapy to her growing list of MS treatments. Chelation comes from the Greek word chele, meaning “claw,” as the therapy is meant to grab on and flush out heavy metals like lead, iron or mercury. Currently the FDA endorses the use of chelation therapy for lead poisoning. Sikora’s alternative medicine doctors believed MS may be caused or progress by a high toxic load. The therapy was intended, therefore, to remove these toxins that may have caused Sikora’s cells to stop communicating properly.

As Sikora grew older she replaced her Copaxone treatments with different alternative therapies. She sees a homeopath and goes to an acupuncturist who treats many MS patients. She attends pilates to stay in shape and ease through her body strains. And with no direct side effects, these treatments provide some hope to other autoimmune patients. Even if the therapies do not slow the progression of the disease, at least patients know they are actively fighting to gain control of their bodies.

Organizations like the S.L.E. Lupus Foundation and National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS) create a community for autoimmune patients to turn to as their disease progresses. They provide support groups and hold research seminars to update patients on the newest available treatments. They are also indispensable advocates for their patients.

For one week every March the NMSS hosts activities throughout the country to promote awareness of MS. Each chapter organizes special events to unite patients in the local community.

On March 11, the NMSS and New York University Hospital for Joint Diseases collaborated to hold a wellness event to honor local MS patients. The director of the program explains that the event is one of the few social outings patients attend regularly. It is an opportunity for patients to enjoy free lunch, free massages, and free yoga. But the highlight for many of the MS patients is the return of the hypnotist.

“Imagine yourself at the faraway lake,” says a reading passed out at hypnotist’s class, “sparkling in the late afternoon sunlight. You are sitting in a comfortable chair with a pair of binoculars (if you want the binoculars; if not, you can simply adjust your eyes). Watch the tiny waves, the reflection of the world around. And look, in the distance, you see a flash of color, or something that catches your attention.”

While not the real thing, the hypnotist explains that self-hypnotism can be an important tool in dealing with the pain associated with MS. She tells the class she suffers from MS and that before she could not fall asleep at night because of the burning in her legs. But then she started visualizing ice cold water running through her veins and down her legs. With time the pain in her legs disappeared. She says that she used to feel off balance, but then she visualized herself with very large feet.

Though hypnosis does not cure MS, it can relieve the pain of patients with more severe forms of the disease. It provides the hope that though MS, or any other autoimmune disease, may not be curable, it can be lived with. Small mental boosts from temporary pain relief are integral to improving patient’s physical state. Without the resolution of their physical pains, patients can be consumed by hopelessness, consciously or not.

“I went to sleep one night, and I remember I saw a big black gun,” says Webber of the time when her Addison’s was at its worst. She explains that this is not a story she likes to share, but it’s the genuine fear that remains in her voice that’s disconcerting. “I remember I prayed to God that night, and I don’t pray that often. I said, I know everyone says that you don’t give us more than we can handle, but I think you misjudged me this time because I can’t handle any more. I need a reprieve. I can’t handle this pain. And it was all to myself, and I never told this to anyone except my therapist when I got better. And the next day, honest to God, I had a day where I wasn’t in pain.”

Information from AARDA

Coping with autoimmunity is not only about accepting the diagnosis and its physical limitations; it is also about learning to live with the disease. Patients learn that though the disease will always be a part of them, it does not define who they are.

Marc chooses to adjust his life around the disease. He accepts that some days he may have to leave work early because the pain in his back or hands is too strong. He understands that at the end of a work week he must take a day to recover. In the past few years Marc’s symptoms have continued to progress. Marc explains that as his disease becomes more visible he feels the need to share his diagnosis. “It’s something that I have that people don’t understand,” he says. “They don’t know that it’s painful.” Now Marc sees it as his responsibility to spread awareness of a disease that so many others struggle with silently.

Other patients see their disease as motivation to change their lives. Maria says, “I want to take advantage of everything that I can.” She explains that before her diagnosis she was a classic over-thinker. Now Maria has four tattoos and raves about her sky-diving experience. She understands that her body may not always be healthy, but the good days are worth celebrating.

Unfortunately, most of Murphy’s days remain difficult. She has not yet found the appropriate treatment to balance her symptoms, but she has found a new way of dealing with her isolation. She recently joined an online support group that allows her to chat via webcam with other chronically ill patients.

Webber became a representative of the New York City Chapter of the National Adrenal Disease Foundation (NADF) after her diagnosis. Through the NADF, Webber met people who were also dealing with similar challenges. But she will also never forget the people that helped her through her along her journey to a diagnosis. “With every challenge comes a silver lining,” Webber says, “and I would never have met the people I have through the past 10 years if it weren’t for my diagnosis.” Though she is now focused on getting her life back to normal, Webber still takes time to visit other friends in NADF when they are sick. When she speaks of her disease she says, “I don’t know if it’s been a blessing. It’s been my journey and I’ve learned so much.”

Ladd has dedicated her life’s work to autoimmune disease awareness. She is a member of the United Nations Non-Governmental Organization Health Committee, received the Heritage Award from the Johns Hopkins Alumni Association and, in 2010, won the AESKU.AWARD for her “lifetime contribution to autoimmunity.” Ladd explains that one day she hopes to write a book titled “Pearls of Wisdom” containing tips on how to live life with an autoimmune disease. But for now, her main goal is to unite autoimmune diseases into one broad category of diseases that affects one out of every five Americans.

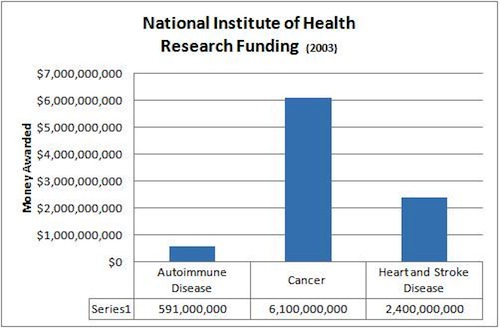

Ladd says, “Think of a train. Each one of these diseases is one of the cars on this train. We don’t know the mechanism and we don’t know the basic immunology behind what is causing the mechanism that initiates it. It might be different mechanisms for different diseases, but that basic autoimmune research is way, way underfunded. And we’re not going to get a cure till we find out what the engine is.”