Todd Sestero pulls a carefully labeled slide from a neatly labeled box. He holds it up to the light and studies its tiny image. It’s a photograph he took almost forty years ago, just after his family moved to Baltimore. “It’s all trees and everything,” he says, “except one little spot you can see the engine and you can see the fact that it says ‘PC’ on it for Penn Central,” a railroad line that lost its name during the mid-1970s in a merger to form Conrail. It’s that one little spot that Sestero treasures, this tiny moment of rail legacy that he managed to catch on film.

“As we get further away, some people say ‘I don’t want this stuff,’” Sestero says of his aging memorabilia. “It becomes rarer and rarer.” The 60-year-old shuns photographs and instead develops everything into slides, attracted to their crispness and the certain feel they have when he looks at them. He started taking photography seriously in 1969, and in the decades since has tossed almost nothing.

Forty years’ worth of photographic train history is packed into a single shoddy bookcase tucked in the corner of Sestero’s basement in Baltimore. The shelves stretch six feet across and stand nearly seven feet tall. They’re lined with a series of neatly upturned slide boxes – blue, black, and brown – each holding as many as 600 slides. Never having actually counted, Sestero does the math quickly and figures there must be between 55,000 and 60,000 slides in total. There are about a hundred boxes and each is nearly full. “They’re all really anally labeled too,” he says. “Every slide is numbered – all sixty thousand slides has an individual number on it – like a roll number, then a dash, then the number of slides in the roll. And then I have log books that I keep this all in.”

It’s Sestero’s hope that one day retirement will open the door to more unclaimed time that he’ll use to digitize the enormous collection, put it online, and make it available to the thousands of other rail aficionados like him – adding the slides to the web site he’s already set up with maps and tips to help guide traveling train spotters.

Inside the threads of massive online forums and in the pages of specialty magazines, rail lovers share stories of train sightings, plan trips to spot for rare locomotives, and post pictures of their successful efforts. They call their actions “railfanning,” themselves “railfans,” and they share a fascination with this clunky, seemingly outmoded form of transportation. For a railfan, a passing train at a railroad crossing isn’t an irritating delay; it’s a blessing. It’s a chance to marvel at the engineering accomplishment that is a train, a vehicle that makes it possible, as The Economist noted in 2010, to move a ton of cargo as far as 450 miles on a single gallon of fuel. Railfans stand in awe of a locomotive’s towering fifteen-foot height, reveling in the overwhelming power of a 10,000-ton train as it hurtles by at full speed, steel pounding steel, the howl of displaced air. Standing in front of such enduring technology, they travel back to a time ruled by the rail and see the history of a country built by it. Waiting for hours to share a moment with something so much greater than themselves, something that has lasted through the changes of modernity, they admire the longevity of trains and their evolution. For Sestero and his counterparts, the train is beautiful, an object of grandeur and accomplishment; they love it. To them, rail is a constant feature of America’s ever-growing infrastructure: a mobile backbone to the country’s economy and an expression of strength and size moving with grace and ease.

High in the Allegheny Mountains a sign on an old converted post office marks the elevation at 2078 feet. There’s no cell service and the air is cool and clear. Only a dirt road leads from the main highway. In the distance, behind the defunct green post office, is the Mance Training Camp, a railfan oasis that looms atop a grassy knoll, like a gleaming watchtower with 360-degree views of encircling railroad track.

The Mance Training Camp (Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

The Mance Training Camp (Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

The camp is a bastion of solitude for its builder Roger Snyder, who retreats to Mance, Pennsylvania and his “railfan paradise” as an escape from his day-to-day as a land use planner in Virginia. In square footage it isn’t big, an 8 feet by 12 feet cabin and a surrounding deck, but its reputation within the railfan world is close to legend. The most recent incarnation, which Snyder rebuilt last year after a fire destroyed the long-standing original, has the distinctive silhouette of a classic caboose car – painted red to match. The proportions are a little small, but looking inside it’s easy to imagine rolling cross-country in something similar.

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

There’s a bed at one of the shorter ends, turned long ways and tucked just perfectly between the encroaching walls. On it there’s a green fleece blanket printed with the words “MODEL 40” and the image of a John Deere tractor. The rest of the furniture, a plush “master” recliner and armless cushioned “guest” chair, sit pushed against the wall. Everything is a little too big for the compact cabin, but it fits in a Mattel toy camper sort of way and leaves just enough room to take a seat and grab a beer from the mini fridge under the window. The plywood walls are unfinished but it’s easy to feel comfortable.

Snyder comes up to the camp every few weeks to sit, usually alone, and watch as freight trains navigate the risky climbs and descents through the mountains that surround Mance. Hours tick past on the gimmicky clock over his bed; it’s shaped like a giant leather-strapped watch. There are the trains and Johnny Cash on his MP3 player. When Snyder gets hungry he’ll drive over to Meyersdale a few miles away and catch up with locals at the G.I. Dayroom Coffee Shop. It’s a simple, no-frills diner: the kind of place with a tight-knit clientele whose every head snaps to look at the door when it opens.

“Wisdom is the emancipation from the tyranny of the here and now,” Snyder says often. It’s a Bertrand Russell quote, his favorite. “And perhaps I go to Sandpatch, to Mance, to get wise.”

Planted ninety miles southeast of Pittsburgh, Mance isn’t really a town; “it’s just a grouping of a few houses,” Snyder says. Aside from some old barns and the train tracks, there isn’t much to draw outsiders. Snyder built his train-watching camp on the hill behind one of the farmhouses that make up Mance. It stands in the middle of one of railroading’s rarities: a true horseshoe curve. East- and westbound trains, sometimes as many as 25 a day, slow as they climb the steep grade and navigate the tight curve. Much like it sounds, the track at the MTC takes an uncharacteristically aggressive bend, a “C”-shaped curve only about a quarter mile across. The untrained spectator stands on the deck and anxiously looks to the east and west, eying both points where the track disappears behind neighboring ridges, waiting for the startle of an air horn or the flash of a headlight in the distance. But Snyder has been at it too long to be left waiting unawares. He alternates between the three railroad radios he’s set up at the camp, listening for the garbled, cryptic signal crossings as they’re called by approaching trains’ engineers. The radios – one in the former post office, which he and his brother have converted into a basic but manageable studio-type lodge; another in his Honda CR-V; and the last in the red camp cabin itself – are always on, and they chirp frequently through idle conversation. To the uninitiated he narrates the movements of oncoming trains like a conductor announcing upcoming stops. The train’s three signals away, and then two, and then it should be any minute. Moments later the nose of a blue and yellow CSX engine peeks into view from around the distant bend. Slow and cautious, the train curls around the camp’s raised perch, surrounding it on three sides and bleating under the strain of its westbound climb. For Snyder this is the crème de la crème of railroading and rail watching. In the mountains at Mance locomotives are pushed to their limits, always only one brake malfunction away from a derailment. A train’s successful passage is an accomplishment in the taming of gravity and mass, man and technology overcoming the ever-present threat of catastrophe.

“There’s a pusher,” Snyder says. A pusher is railroad speak for a trailing locomotive that helps the heaviest loads negotiate treacherous mountain terrain safely. As the name suggests, it’s an engine that pushes the car set from the rear, while the main engines pull ahead. He makes the call after eyeballing the spacing between cars, he says. With a simple locomotive set up, where a lead engine pulls the cars, the distance between coupled cars will generally be uniform. But when there’s a pusher, cars nearer to the rear start to bunch up together under its force. That’s what Snyder’s spotted. He’s been seeing cars do the same thing since his introduction to Mance in 1987, a quarter-century ago. Snyder was working in Manassas when his rail interest hit a renaissance. He’d heard the area at Mance, also known as Sandpatch, described as a “scenic spot and less overrun by railfans than the often talked about horseshoe curve to the north,” the one at Altoona that boasts observation lookouts and draws railfans and general tourists alike. Snyder towed a travel trailer the 150 miles from Manassas to Mance, alone, and set up camp next to the tracks on railroad property to enjoy the “solitude and the countryside and lots of trains.” After three days Snyder was hooked.

Horseshoe curve at Mance, Pennsylvania (Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

Horseshoe curve at Mance, Pennsylvania (Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

By 1991 – half a dozen Mance trips later – Snyder was ready for something more permanent. He discovered his camping spot was actually private property and went about getting the rights to use the land for $100 a year and the promise to take out liability insurance. It was a steal. Just six vertical four-by-fours and a roof kept the sun or rain at bay for a long day of train watching. At first it wasn’t much more than a high iron picnic shelter, to borrow a term for the high-grade, long distance track used on freight mainlines. Slowly it grew into a true cabin, and everything at the camp, including a full-size Barcalounger, was scavenged and hauled up to Mance by Snyder. “Somebody else’s trash became our treasure,” he says. It was all “sort of like a beaver building a dam,” piecing the place together from nothing. And it was then the camp got its name. “I had the bright light bulb idea of, well, let’s do a play on words: it’s Mance, I like trains, and I like to camp,” Snyder says, “so it’s a Mance Training Camp. And the rest is history.”

The train passes a few minutes later, brought up as promised by a smaller CSX locomotive. When calm settles back into the mountain valley, Snyder looks over the surrounding cornfields and wooded forest beyond. He speaks slowly, cleanly. “One of the draws [to the camp] is that it’s very similar to the farm area where I grew up.” Snyder spent his youth working. It was rough country labor and it gave him an informal education in carpentry, electric wiring, and plumbing – skills later put to use building the camp at Mance. “Maybe that’s why I wanted to become an engineer,” he says of his early vocational interest, “because I already was one, de facto.” As a college student at Dartmouth, though, engineering fell by the wayside and geography took Snyder’s attention. By then his childhood love of trains had developed into an adult passion and, searching for a senior thesis topic, Snyder aimed for something that would blend his two loves: geography and railroads. He settled on a survey of the now-defunct Vermont Railway and called it “Twilight Comes to a Short Line.”

Like many railfans, Snyder pins the birth of his interest on a relative, his grandfather, who lived in West Hartford, Connecticut. Snyder and his twin brother started working on the “hardscrabble, non-profit” farm when they were five, doing whatever they could physically, and “our only escape from child labor was going to visit our grandparents,” Snyder says. “My grandfather had a nice Lionel set in his basement, the kind that old people had, with all the bells and whistles – and that means literally bells and whistles, not figuratively speaking.” Snyder and his brother would pore over black and white photographs from their grandfather’s worn albums, sifting through rail pictures snapped through the 30s, 40s, and 50s, and eventually they’d get the question: “You boys wanna see some trains?”

“It was nothing more than going down to a crossing,” Snyder says of his first railfanning excursions. They would watch the 515, a passenger train on the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, as it roared past. In those years Snyder’s interest grew from a childish desire to relate to an older relative into a full-fledged passion of his own. But on those early trips it was little more than a child’s love, Snyder says, “a love for a family member, where, okay, my grandfather likes trains; I like trains because I like my grandfather. If A equals B, B equals C, then A equals C. So that was the start.”

Sarah Warner gets the order and knows she has two hours to report for work at CSX’s Osborn Yard in the heart of Louisville, Kentucky. The 25-year-old lives her life like this, on call, waiting to fill in on a shift working for one of America’s freight rail titans.

“P”

An hour later Warner is raising a gloved hand to wipe water from her eyes. She scans the light board a few yards away to see which cars are assigned the letter. Warner’s job tonight is to work the hump, a man-made hill in the center of her yard; rain pelts down as it has for most of the night.

Half a mile down the track a towering locomotive slugs forward, edging the car nearest Warner to the crest of the hump. She identifies each car by a four-digit number stenciled on its side and “pulls” whenever a “P” precedes a car’s number on the board. For all the innovations in greener, fuel-saving locomotives and automated dispatch software, joints between freight cars still require a manual pull to disconnect.

Warner is quick and the pin comes easily. She steps back and radios for the push. The locomotive moves again, slowly, just enough to nudge the car in front of her over the hump’s crest to roll smoothly down the hill, where it veers onto one of the dozens of smaller tracks in the “bowl,” railroad slang for the track beyond the hump, which splits so many times it fans out and starts to look like a fish bowl.

Paying as much as $260 a shift, the hump is one of the higher compensated jobs a yard employee like Warner can get. And even after five years, she’s still relatively new to the yard, which means she’s subject to the on-call rotation and never knows exactly what she will be doing from day to day. But there’s excitement in that for the Philadelphia native, whose passion for trains as a teen led her online, where she spent nights in high school connecting with fellow railfans. There was a comfort online, where she posted under the username CSXrules4eva, and found others as excited about trains as she was. She would photograph passing Septa trains at a crossing ten minutes from her house and, once she was old enough to drive, take longer trips out to Abrahams yard to watch for the larger Norfolk Southern freights. Trying to hammer out what it was that first drew Warner to the tracks is a challenge, but it was probably always rooted in a visceral desire to explore the contrast between size and control. Standing just a few feet from a racing train, one can’t help but be intensely aware of how delicate the whole operation is. Its strength is readily apparent, but then there’s the realization a few moments later that something really could go wrong, that there is just one person, sitting in a cab at the front of this rolling chain of mass, who stands between restraint and the violent forces of physics. Warner remembers being captivated by the idea: one person, the engineer, “could be in control of all that tonnage.” And not only that, but all that tonnage could move with relative grace and precision. “You wouldn’t think an 8,000- or 10,000-ton train could move like that,” she says.

After graduating high school, Warner applied to CSX and Union Pacific, two of America’s largest freight rail companies, hoping to get a job as a conductor. She’d known for a few years rail was going to be her future, but she also knew she’d need her mother on board before any of those dreams could become reality.

“She was thinking minimum wage,” Warner explains. In high school Warner was a model student, a member of Youth and Government and Future Leaders of America, and her mother was envisioning a political science degree in her future. The mental image of Warner working for next to nothing on a bunch of dirty trains was something she couldn’t get over.

Warner had kept her rail passion quietly separated from her academic studies, but she’d also spent a considerable amount of time researching the job prospects held in a railroading career. She wasn’t public about being a railfan with her friends at school. Only a few people knew about her interest, but she was able to ask some friends she made online about her options and gather enough inside information to figure out the kind of job she wanted. It was tense for a while, Warner admits. Her mother, a children’s hospital lab technician, didn’t say much at first; instead, Warner remembers the brutally silent “excuse me, oh, no” face her mother made. Ultimately, though, she acceded to her daughter’s research and resolve, leaving Warner with just some mild skepticism from friends.

Surprisingly the ribbing didn’t come from outsiders who failed to understand her unpopular hobby. Warner says most people are nice enough about her interest, and now her job, even if they don’t get it. Instead, the joking came from some of the friends she’d made who worked for passenger railroads in the Philadelphia area. “‘You’re a nice girl. You need to be on a passenger line,’” Warner remembers them saying. It was a close-up confrontation with the rivalry that stands between American passenger service and freight companies. There’s no love lost between the two, Warner says. One friend’s words made the disdain clear: “Freight railroad is for girls who don’t have teeth.”

Railfans say there’s no such thing as your “typical railfan.” They concede that the stereotype is middle- to old-aged white men who have far too much time on their hands after retirement, but they make it clear that’s only a piece of the story – that, really, it’s impossible to pack the countless distinct types of railfans into one character mold. Some look for companionship in a shared interest, while others like Snyder are happy to retreat to a weekend alone at Mance. Some carry neatly ledged notepads, meticulously penciling things like schedule deviations and locomotives’ different braking systems with extreme precision. Others eye the note takers with an amused confusion, calling them “rivet counters.” And then of course there are the “foamers,” the slack-jawed obsessed who froth at the mouth like rabid dogs when they see a train. They’ve become the butt of jokes by some railroad engineers who tease fans by brushing their teeth at strategic times, foaming up their own mouths as they pass the gathered groups.

The majority of railfans seem to fall into a middle ground between mindless foamer and studied rivet counter. But most share the same appreciation for history, married with a study of technology and movement. Rail cars, despite their frequently graffitied and battered appearance, last a long time – half a century, often. For a railfan that means that looking at a train car is an experience far more complicated than just appreciating an accomplishment of monumental engineering; it is a study of fifty years of history in one vehicle. Perhaps that was part of Warner’s own attraction, the way the rail and the physical history of each car offer a tangible tie to the past, allowing her to experience in a new way the stories she grew up hearing. Warner’s great grandfather, a man she never met but thinks of as her “greatest influence,” spent a lifetime on the Pennsylvania Railroad, and from tales passed on from her grandmother, Warner figures railfanning is in her blood. One of her favorite stories is a trip her great grandfather took one week when his family thought he was out working on a derailment clean up. He woke up one morning, boarded a daylong train to Florida, and when he arrived, boarded the first train back to Philadelphia. It was a true ride-for-the-rails trip. He, Warner says, “was a definite railfan.”

Warner, who has a love for history, points out that train watching used to be an activity for the masses, not just a niche hobby. “Technology’s come a long way,” she says, referring not so much to rail’s evolution, but to how television and the Internet have changed the way we all pass time, how easy it is to be entertained endlessly on our couches. When Warner is able to get out and catch sight of an historic steam engine or another antique restored locomotive, she’s transported to railroad’s golden age. “It’s a way of bringing me back to the excitement [of the past],” she says. “Back then people didn’t have a TV; there was nothing they could really watch, so they went out to see the train as it came through town.” They weren’t railfans per se, but watching trains was still an event.

After convincing her mother that working for a railroad wasn’t a dead end, Warner waited nearly two years to hear back from CSX and Union Pacific. It was enough time for her to get an associate’s degree in automotive technology and nearly give up on the whole thing. Finally she got a long-awaited call from CSX to schedule an interview. It went well and she was invited to a five-week intensive training session known as “railroad school” in Huntington, Virginia. There she learned to identify signs and signals used out on the tracks – old hat for a railfan like Warner – and taught herself the coded lingo of a conductor. Words like “drill,” “couple,” “shove,” and “joint” took on new meaning. For many, Warner says, the railroad is just a job. Even today she still calls herself a closeted railfan when it comes to her coworkers, few of whom share her appreciation for the grandeur of the locomotives. But for Warner it is the ultimate marriage of work and play, the logical next step for a rail lover. Doing anything else would be just a job. With her schedule, Warner has precious little time now to do the train watching she loved as a teen, but finding a job that pays her to hang around trains all day affords her a valuable luxury, she says. “Now, I do most of my railfanning at work.”

Sarah Warner (Photo courtesy of Sarah Warner)

Sarah Warner (Photo courtesy of Sarah Warner)

Tonight Warner is back at Osborn Yard. She parks her Jeep and kills the engine in front of a low, one story building. As she hops out gravel crunches under her Nike sneakers and a small sign she’s fastened to the passenger seat belt shakes silently: “This locomotive is equipped for remote control operation.”

Warner heads straight for the building’s modest break room, where a pair of computer terminals flash rail jargon wholly indecipherable to an outsider. Across the room is a set of plain, waist-high cabinets. She pulls a reflective green vest from one of them. Warner reports here when she works a shift as one of the yard’s remote locomotive operators. She’ll grab one of the heavy car battery-sized remotes stashed in a neighboring cabinet and clip it to the front of her vest, over her stomach. The box lets Warner walk a good distance up the track and then control a locomotive further down the line to push and pull cars to her. She says it’s a lot like running a life-size Lionel train set.

The vigilance beep, which sounds intermittently to prevent distraction, is a reminder, however, of the scale Warner has graduated to and the danger that accompanies it. It’s impossible not to be aware of the risk that comes with that much power, and maybe that is the thrill for her, to know what’s on the line. In her spare time Warner also practices Jiu Jitsu and serves as a volunteer firefighter, which makes one wonder if the adventure and the danger might be more intoxicating than anything else. The remote locomotive is a long way from the model train system she set up and ran in her room as a teen, and looking at her one is struck by the notion that the toys haven’t really changed. They’ve just gotten bigger.

Snyder’s years at the MTC are filled with one-of-a-kind stories he calls “Mance Moments.” In a move of self-reflection, he says he’d like someday to write down a collection of the moments to capture an essence of the camp, and what it’s seen. It gives the sense that Snyder is more than aware of how strange and curious his modest outpost must seem to outsiders. Even his wife, who Snyder says only tolerates but doesn’t share his passion, avoids trips up to Mance.

It’s difficult for a non-railfan to imagine standing beside the tracks one night and paying close enough attention to a passing train to realize, as Snyder did, that a single axle on one of dozens of loaded cars had stopped rolling. It was sliding and grinding down, incredibly dangerous and almost certain to cause a derailment if left unaddressed. It’s illegal for civilians to use railroad radio frequencies to send private messages, but given the emergency, Snyder took the risk and radioed a distress warning notifying the engineer of what he’d seen. The engineer pulled to a stop and Snyder was right. Over the years, saves like that one have earned Snyder some credit with the engineers who run the routes through Mance, and occasionally they’ll offer him rides as a thank you for his watchful eye. These trips give Snyder a taste of life as an engineer. But it’s all from a safe distance, and on his own terms. By cordoning off trains to the realm of hobby, Snyder’s been able to keep avocation and vocation fiercely separate and avoid responsibility and obligation clouding his weekend respites. The division lets Snyder maintain the same boyish interest he had in his youth.

The technology’s changed – the freights and daily Amtrak trains that pass through Mance are all diesel powered – but when Snyder steps out onto the deck of his hilltop lookout, he’s reminded of the tree house he and his brother climbed into as boys to watch the steamers pass on the Harlem Division of the New York Central line – how they’d watch for the rising plumes of steam, which they’d see well before any shining steel. The camp is its own kind of nostalgic hideaway, where nature dominates and technology is easily forgotten. There’s a quiet and a calm in the air, and a feeling that you’ve escaped to this little piece of something that’s just yours, or really, just Snyder’s. It’s the same sense of exploration and independence that drives kids up into trees and out into the woods to build forts from fallen branches and tattered tarps. Train watching never seems to escape its truly childlike nature – that unabashed desire to hold onto some link to youth and bring a distant past closer. Standing just feet from the cabin’s solidly carved dark wood bed, the same one he slept in as a farm kid just happy to please a train-loving grandfather, Snyder thinks it’s very simple. “As an adult, I do what kids do,” he says. “Kids build a fort; I built a man cave and watch trains.”

Sixty thousand slides ago, Todd Sestero got his first taste of taking train pictures wielding a small Kodak Brownie camera at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. Without a magazine, the bare film had to be loaded into the camera in the dark; his father had done it. At the fair, Sestero snapped photos of the GP30, General Motors’s shining locomotive. The camera had a fixed shutter speed and there wasn’t much he could do with the F-stop to adjust exposure, but at the end of the day Sestero came away with one photo that he says actually kind of turned out. “So I got the bug for taking pictures.”

Sestero, a self-described “rail nut” – a term he uses more often than railfan – recognized the GP30 straight off. He’d seen the same model two years earlier in Tyler, Texas, the town of 100,000 he called home from age 8 to 12. General Electric had an air conditioning plant there, and in 1959, Sestero’s father moved the family to take a job in marketing. Sestero would pass the time riding his bike down to the tracks a quarter mile from home. It was something he did on his own, each trip its own adventure. Eventually, he started to follow the tracks from the streets and discovered they came to a railroad yard about a mile down. There was no Internet to welcome his photographs, no friends at school interested in trains, no one to rush to and share his discoveries, so he lingered. “I was down there all the time,” he says. “Most of the guys that worked there at the railroad yard got to know me, and a couple of what they call ‘hostlers’ – they have the job of moving engines around the yard, they can’t go out onto the mainline, but they can move engines around the yard – they would give me rides every now and then, which was pretty cool.”

Sestero quickly became enamored with the world of trains. “There was no accounting for me,” he says. “I was a loose cannon.” Tearing off to the rail yard was an escape from mundane school days and summer afternoons at home. “I would play hooky,” he says. “That was pretty sad, huh? In elementary school, playing hooky.”

The GP30 was his favorite. An especially tall locomotive, Sestero says it’s hard to know exactly what drew him to it. He remembers the rounded corners on the engine’s cab – distinct among railroad locomotives – and a special set of resistors, a supplement brake system, different from any of the others he saw on trains at Tyler. Sestero spent hours at the local library soaking up as much as possible about rail history and technology. “I was really the only one that I saw that was really into it like that,” he says. “There were probably two and a half dozen kids about my age and I’m the only one of all of them that I know of that had an affinity for trains. Not really sure what everyone else was into.” Sestero was only vaguely aware that others existed out there who gave trains a second thought. He’d only just come across a model railroading magazine during a vacation to New York City, and in his four years of trips to the Tyler yard, Sestero never came across a fellow railfan. He devoured the children’s section at the library but wasn’t impressed “because kids books on trains were so simplistic, they didn’t really tell you anything. It’d be like going into college and then getting a book from the fifth grade.”

When asked how the Internet would have changed things for him as a nascent railfan, Sestero doesn’t hesitate. “I’d have learned a whole lot more, a whole lot sooner. I don’t even have to think about that one. If I’d had access to the information kids do today, I could have found out about everything.” Sestero’s envy of a younger generation’s access to information is understandable. The resources out there today for a beginner railfan are astounding. Sites like Railfan.net , Railroad.net , and Trains.com , boast communities of thousands of members and forums with hundreds of thousands of posts about every nook and cranny of American railroading. Posts about company logo changes, correct band frequencies for railroad radio scanners, changes to paint schemes on historic locomotives – it’s all there, neatly sorted by company and region. On a smaller scale, many fans run community groups through sites like Yahoo, where they can narrow their focus even more. Members of the Hudson River Rail Lines group often exchange dozens of emails a day about rail minutiae in the New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut area. They warn fellow fans that a certain usually out of service locomotive is running that day so those further down the line can be sure to see it; they record and post videos of sightings for one another; and they organize meet ups to work on restorations of antique engine models.

A railfan from San Francisco who wants to do some train spotting in Pennsylvania can visit a site like RailfanGuides.us , where he or she will find step-by-step instructions and maps leading toward primo spots to catch trains. The Railfan Guides site is Sestero’s own contribution to this user-created and user-distributed encyclopedia of Internet rail knowledge. They started in the 1980s as just a few scribbled down maps Sestero drew for himself. City maps, he’d found, didn’t have any train information, so he and friends like him had to rely almost exclusively on word of mouth. Traveling for pleasure and later for work, Sestero built up his private guidebook, imagining someday he might publish it. But with the advent of the Internet and the opportunity to create something he could distribute for free and could always keep up to date, he decided to put it all online in the mid-1990s. The guides are an attempt to even the balance between adventure and planning when it comes to railfanning. There’s an excitement in discovering something unexpected, in happening upon a rail rarity or an especially interesting vantage point to use to take pictures. But relying on the hope that fate will strike can waste a lot of time, Sestero says. The guides are a way to cut down on the minutes or hours between setting out and actually finding a train. That way more time can go into photography, an aspect of the railfan experience that is interestingly interactive. For many, it doesn’t seem as much about catching the moment on film, or even being able to show the photographs to friends. It’s about a more immediate need to engage in some way with the passing train, to insert oneself into the event somehow, as though viewing and capturing a fleeting scene via a lens does something to elevate the experience beyond giddy excitement. It’s purposeful and studied. Getting the best photo, with the most interesting layout and composition – less foliage, more nose, less sky, more snow – becomes the game, even eclipsing the wonder of the train itself. But the game takes time. You don’t get as many pictures without knowing where to look. And Sestero is all about taking pictures.

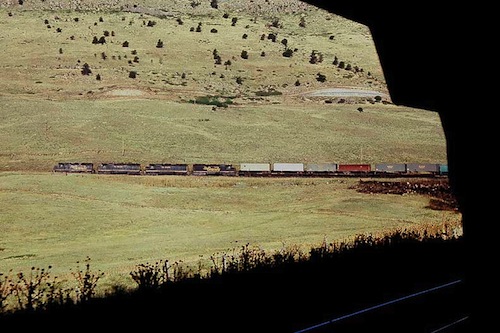

In 1971, Roger Snyder had no guide to go by. There were no regional groups he could turn to for advice or train schedules he could print off the Web. And yet, as his watch ticked toward noon on a perfect August Sunday, he and his wife sat hunched on the flat, hard floor of a steel freight car, hours outside of Denver. Snyder was halfway through his “Sunday Hobo” ride, a twelve-hour journey he took as a stowaway on a westbound train out of the Mile High City.

Snyder had pieced together a bit of the Denver and Rio Grand Western line’s schedule through conversations with area railfans and from his own train watching in the few days leading up to his planned trip, but even today he remembers that Sunday spent in the flatbed of a trailer car as an example of right place, right time perfection.

The twenty-something couple hopped the train at the Denver yard around 6:30 a.m. It was a warm, clear day that wouldn’t demand anything heavier than the matching denim jackets they both wore. Inside the car there were no benches or seats, nor room to hang your legs; it was a ride that demanded the sacrifice of comfort. The smell of diesel fuel and the clattering of steel on steel filled the dark container, a severe contrast to the rolling scenery unfolding beyond the freight car: mile after mile of moving landscape.

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

Through the side of the trailer, Snyder reveled at a natural beauty so different from the “manmade ugliness” he calls cities. Around noon, halfway into their daylong trek, the train reached Bond, a rest stop for the railroad with only a café and a small three-room motel for employees to catch some rest between shifts. As they came into Bond, Snyder realized the train wasn’t going to stop; it’s not uncommon, he says, for a freight train to conserve fuel by passing through a yard without coming to a full stop. Employees board and leave the train after it slows to about five miles per hour. Snyder reckoned he and his wife would have to do the same if they wanted any chance of catching a Denver-bound train later that afternoon and getting home that day. They had to jump.

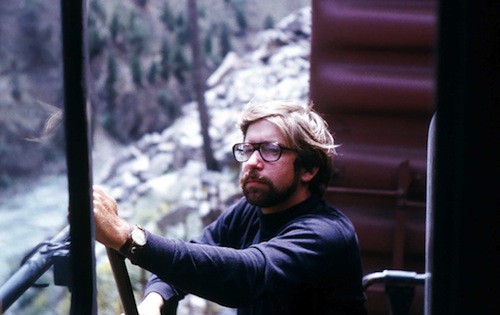

Their adventure revved up when the couple ventured into the café for lunch. They were lucky enough to rub shoulders with a young engineer who told them that the last engine on the next Denver train would be unmanned, working as an extra “pusher” locomotive through the mountains. If they could hop on right before the train left, after the initial walk through, they’d have a much more comfortable ride.

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

(Photo courtesy of Roger Snyder)

Looking back, Snyder knows how incredibly lucky he was. If there hadn’t been a train back to Denver that day he’d have been forced to beg to rent a room for the night. Instead, it all came together. The engine cab felt like luxury compared to the trailer bed where they’d spent the morning. Snyder was on his ultimate railfan trip, sitting in the padded engineer’s chair, live controls within arms’ reach. He listened to the engineers over the live radio and figures he could have pulled the brakes if he’d wanted to. But sitting back, a captivated observer, it was the closest Roger Snyder would ever get to running his own rig. It was all the thrill with none of the responsibility, the afternoon of his life.