From his small apartment on the sixth floor of a walk up, deep in the twisting streets of Chinatown, Tenzin S. sighs and shakes his head. Moments earlier, he had opened the heavy, gray metal door that protected the entrance to his building and beckoned me inside with a smile, his small figure clothed in a well worn sweatshirt and green work pants. “No elevator,” he said simply. He led me to the base of the chipped, gum-spotted stone stairs and began the uphill hike. Despite his aging appearance, he powered up the steps at a shocking pace, making it difficult to keep up.

Now he sits cross-legged on the carpeted floor of the room he reserves for his altar and guests when they visit. The room is filled with Buddhist and Tibetan religious objects; on one wall hangs a colorful prayer rug, woven in an elaborate pattern of twisting geometric shapes. Adjacent to the rug is the most important object in the entire apartment; the altar. Each morning he places fresh bowls of water there in an offering of generosity to the gods.

Today Tenzin S. is telling me about his latest project; for months, he has been rewriting Tibetan history for the classes he teaches to Tibetan children on Sundays in Queens. His goal is to produce a history book that tells the ‘real’ story of what happened and is happening in Tibet.

Tenzin S. launches into a story about Songtsen Gampo, the 33rd king of Tibet. His roommate Samten and her friend chime in with their own details. When Samten realizes that what she’s saying is being recorded, she quickly says, “Oh, I must be careful! I’m going to shut up my mouth!” but shortly afterward she talks again.

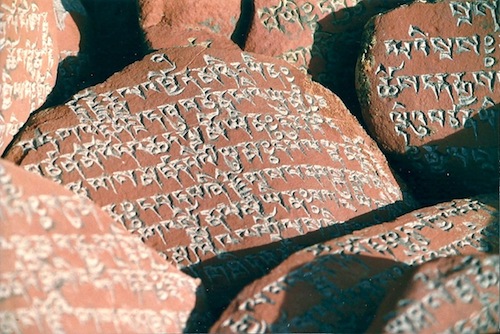

Tibetans love to speak about the 33rd king, as he was the first person to have Buddhist scripture translated into Tibetan, bringing the religion to the country. “Songtsen Gampo very good for relationship with China and Nepal,” Tenzin S. says, mentioning that Gampo took both a Chinese princess and a Nepali princess as his brides. “First, Songtsen Gampo ask Chinese king to marry daughter and Chinese king say no. Then he send over a lot of army, a lot of people, and Chinese king finally say yes.” He adds that Tibet was a very strong country during Gampo’s reign in the 600s and neighboring countries had great respect for the region.

This story is no longer taught to students in Tibet. Tibetan history is no longer taught in schools in the region, period. As their heritage is being erased and suppressed by an oppressive government, there has been a large spike in self-immolations, no longer only by monks, but now by frustrated students. A recent article in The New York Times describes the self-immolation of Tsering Kyi and her frustration with the switch from Tibetan to Chinese as the language of instruction at her school. Once an honor student, Kyi’s grades began to slip after her Tibetan textbooks were replaced with Chinese ones.

He stops speaking and gets up to fill our teacups. Drinking Tibetan Tea is a regular habit in the community. Traditionally made with yak butter and salt, the resulting mixture is thick and strong with a vaguely greasy taste. He pads across the thick, maroon carpet into his kitchen, a space containing a fridge that’s almost too big for the room, a miniature stove, a rough-looking cement industrial sink, and a shower. The glass door of the shower has been replaced with an ominous looking black garbage bag taped across its width. Minutes later he’s back, seating himself cross legged on the carpet once again, waiting for his steaming drink to cool. Sunlight streams through the window into the room, its warmth and the silence of the apartment creating a blissfully tranquil feeling.

The project of writing these history textbooks became so important to Tenzin S. that he quit his day job working at Whole Foods in order to strictly focus on going through old Tibetan texts. Eating was an afterthought and he mentions that his fridge was often empty because he was so engrossed in his work. But luckily, he says, friends came to drop off food so that he didn’t go hungry. He points to a shiny new MacBook Pro sitting on top of a desk beside the altar where all of his progress thus far is stored. He rarely uses the internet to help him and when he does, his access is from a wireless network that belongs to another tenant living one floor above.

When Tenzin S. arrived in New York in 1984, he didn’t speak a word of English. Upon his entry into the United States, government officials asked for his full name and date of birth. The second request proved more difficult, as he knew the year; 1937, but was unsure of the day. In Tibet, birthdays are unimportant. There is a much greater focus on significant religious holidays instead. Directed to then simply pick a day for his birthday, Tenzin S. chose a day in the history of Tibet that will never be forgotten – March 10th, the day of the Chinese invasion in 1949.

Shortly after his arrival, he became very ill and was told that he would need to leave the United States and return to Tibet. Going back wasn’t an option for the man who had endured 15 years in a Chinese prison. Obtaining a visa from a Chinese official who had taken a liking to him had been difficult enough, and a return to his home country would mean an existence in a repressive environment with limited freedom to practice Buddhism; the religion that so strongly defines Tenzin S.’s life. Besides that, there were the stormy memories left behind - both of his brothers had been killed by Chinese soldiers. One had been a monk. He was featured in a newspaper in India after his death, photos of his smashed face the result of being thrown from the third floor of a monastery by Chinese soldiers during a peaceful demonstration. “The only way I recognize him in the picture because his name printed at the bottom,” Tenzin S. says.

Luckily, with the help of a lawyer, Tenzin S. was granted permission to remain in the U.S. As he takes sips of his tea, the only sound is the low, monotone chanting coming from the promotional video advertising tourism in Tibet. The monks on the screen look serene and joyful, their deep orange and yellow robes contrasting with the naturally dark pigment of their skin. The monasteries in the background are pristine, rows upon rows of colorful prayer flags fluttering against the Himalayan Mountains. The Tibet on the screen looks like a happy, exotic place; not the Tibet of the newspapers or Tenzin S.’s stories where monasteries are destroyed and people are killed.

Sunday is not a day of rest for Diki. Children are running in all directions, yelling, screaming and laughing. Outside the building, Tibetan parents huddle in groups, catching up, shooting the breeze. Diki is in her mid 30s and is constantly on the move, hovering around, monitoring. In between checking on the classes, she meets with a guest from a Buddhist institution who came to do a special prayer reading today with the children. The woman, Diki hurriedly explains, is helping them to produce a play that they’re aiming to perform in May, an auspicious month in Buddhism.

Throughout the day, I barely see Diki, except when she ducks into Tenzin S.’s class to take care of a troublemaker who refuses to sit on the carpet and behave during prayers. The youngster finds playing with a string much more intriguing than learning about His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. “You disturb all the time,” Diki complains. Finally, peace is restored and the boy sits in line behind the rest of his fellow students. Since there have been more self-immolations recently, today the children are going to have a “special prayer.”

The teacher leading the prayers emphasizes that they are the “next generation” and must help the people in Tibet. “If you want to have a good and successful rest of your day you must pray like me,” she says. The prayer session ends with a Tibetan song, followed by a feeble rendition of the Star Spangled Banner that peters out and isn’t restarted. The teacher shrugs her shoulders and looks over at me apologetically. “They forgot the words,” she says.

Toward the end of the day, as the children are leaving to go home, Diki is able to speak with me in the hallway. Both of us are nearly bowled over by an overly eager little boy running toward the exit in that state of oblivious tunnel vision that all young children have. Diki had the idea of starting the Sunday School to help Tibetan children growing up in New York to “be Tibetan for a day.”

“Sometimes they are like foreigners to us,” she says, referring to the cultural differences between the current generation and the older Tibetans who have immigrated to the U.S. The children look Tibetan and their names are certainly not American. But Diki feels that the current generation of Tibetan-American children growing up in the U.S. struggle with a “confusing identity” where they often find it difficult to fit in. She says that it’s hurtful for the Tibetan-American children, when their friends at public school don’t know where Tibet is. “Sometimes they want to introduce themselves as a Tibetan at school, and nobody knows what is a Tibetan.” This, Diki says, makes them feel sad and ignored. “I want to offer them a sense of belongingness here at the Sunday School,” she says. She wants them to feel, she says, like “we’re all Tibetan and we’re a group here for you.”

Diki needs to run again, so she tells me to come back during the week to talk more, in a less chaotic situation.

Prayers aren’t yet finished and the halls are unusually quiet. A dozen or so copies of Good Parenting are displayed in an artful arc on the table. A large corkboard on the opposite wall has a colorful, attention-grabbing sign up sheet for parent volunteers to help at an upcoming event. All of a sudden the off key strains of Happy Birthday sung by a large group of children come wafting out of a classroom down the far end of the hall. Following next is the sound of shuffling feet as a mass exodus pours out of the classroom into the hallway.

An older boy pulls up his sagging pants, boxers exposed and comments that he should have worn a belt today. His friend shoves him, causing his pants to drop even lower. The chaos in the hall gradually dies down as the children find their way to their respective classrooms. The boy with the sagging pants meanders over and sits down. He wants to talk. Tenzin T. is 13 years old, but pretty much 14, he specifies, as his birthday is next month. This makes him one of the oldest students in the school. He’s good-looking and tall for his age and speaks with the air of someone who’s well liked.

He tells me that his parents keep his home “as Tibetan as possible.” By that he means that the Tibetan language is enforced at home and his parents don’t respond when he speaks to them in English. It’s tough, he says, because it’s not that easy to learn Tibetan. “I mean, I think it’s good, but it makes it hard, you know.” As we talk, other students from Tenzin T.’s class peer out of the doorway of the classroom, giggling.

This past summer, Tenzin T. tells me that he visited the Tibetan Children’s Village in Dharamsala, India. The Village provides shelter to children who have been separated from their parents or orphaned while escaping from Tibet. He says that seeing Tibetan children living in situations where they’re struggling to stay alive really made him appreciate the freedom he has in the U.S. As for what he wants to be when he’s older, well, he doesn’t really know. “But my mom wants me to be a writer and my dad wants me to be a lawyer or an engineer,” he says. What he does know is that he wants to do something to help Tibet.

Tensang wants to be an astronaut. She also wants to be a C.S.I agent like the characters in her favorite TV show. After exploring space and fighting crime, she wants to have a "designer" store like H&M. “But what do I really want to do?” Basically, she says, she wants to be able to go between the U.S. and Tibet to show Tibetans “American stuff” and show Americans “Tibetan stuff.”

“If you become somebody, your parents will be proud of you,” she says. “Like ending up on TV or in the newspaper.” At 12 years old, she’s tall and strongly built. I noticed her earlier in the hallway and remember her light-filled smile and easy conversation with her friends. She’s been coming to Tibetan Sunday School since the first year it opened. She says her parents send her there in order for her to learn to carry down the Tibetan language and culture so that it won’t “vanish.” At home, she tells me that her uncle, who lives with her and her parents, is the most religious of all her family members. “He prays all the time,” she says. “My Dad listens to him, but doesn’t really pray with him that much.” Tensang learns about the prayers her uncle recites at the Sunday School.

Each Sunday the children do prayers for 30 minutes to one hour. “The prayers are like a long story,” Tensang says. Her mom meditates every night. “My mom also cooks really good Tibetan food, like momo .” Whenever mention of these small, meat or vegetable filled dumplings is made, eyes light up and smiles appear.

Dechen has big brown eyes that are magnified by her glasses. She’s 9, and is wearing a sweatshirt that dwarfs her small frame, forcing her to keep pushing the too-long sleeves up over her hands. When she speaks, she has a surprisingly low voice. Dechen came to the U.S. from Nepal, which explains the hint of what sounded like an Indian accent. She tells me, in a low whisper, that when she grows up she wants to be a veterinarian and go between the U.S. and Tibet helping animals. I have to strain to hear every word she says. “My parents pray every morning,” she says softly. Her uncle also lives with her parents and used to be a monk back in Tibet, so “he talks to me a lot about that.”

Tenzin S. is dressed differently; instead of the normal paint spattered work pants and tattered sweatshirt, he’s wearing a pair of brown polyester dress pants, shiny black dress shoes and an embroidered shirt that would appear to be from his home country.

He says that he's dressed up today because he was just at the temple all morning, praying. I find out that another nun has set herself on fire in protest against the Chinese presence, the 11th to do so in recent months.

We walk toward Diki Daycare. On one corner there’s an Hispanic store, advertising dresses for sale in Spanish. A racy lingerie store with a barely PG window display and a J Crew featuring new, bright green khakis sit side by side. As we get closer to the school, Tenzin S. begins recognizing fellow Tibetans on the street, stopping to say hello and exchanging a blur of Tibetan words. I think he introduces me to them, because they all give me a big smile, and a friendly nod. Inside the entrance, a small child runs up to him with a shout of happiness, gives him a huge hug and grabs his hand. Together the two climb the steep set of stairs with remarkable rapidity. All the way up the busy staircase, Tenzin S. is greeted by children running in all directions.

Today he’s teaching the alphabet to the five to eight year olds. Attention spans are understandably short in this age group, so most of the time the focus is more on talk of Power Rangers and what the other dressed up as for Halloween. A young girl, Tati, recently celebrated her birthday. She tells her friends about the chocolate mocha cake that she had at Chuck E Cheese during her party. One little boy walks up to a group of three girls, pushing himself into their closed circle, and proceeds to yell out “who wants to kiss my face?” to a reception of disgusted responses of “gross!” and “go away.”

As he walks around the room, giving out individual help, Tenzin S. taps the boisterous ones on the head with a roll of paper, pretending to be angry. But you can see he really doesn't mean it at all, as he smiles to himself and shakes his head and laughs, his lips breaking apart to reveal his missing tooth. With the more serious ones, he wraps his big hand around their small one and guides their pencil to properly draw the letters of the alphabet. One responds with “thank you gela ,” a term of respect in Tibetan. Upon hearing gela , a boy sitting nearby says “you should have used ‘mister,’ you know.”

After an hour, Tenzin S. and his teaching assistant decide that it’s break time. Immediately the children dig into their backpacks and pull out an assortment of chips, Oreos, and chocolate bars. The crinkling sound of chip bags and candy bar wrappers fills the room. Tenzin S. meanders over to one corner and picks up a plastic bag from the floor. He digs around inside of it and out comes more candy, fruit and granola bars, some of the items half eaten and in differing states of disintegration. He walks around the room, handing out goodies from the bag in a Santa Claus-like fashion.

Because of their poor concentration, Tenzin S. informs the class that there will be an exam on the Tibetan alphabet the following week. The announcement manages to grab the attention of the majority of the class. The rest of the session is spent sounding out the alphabet in a cacophony of different pitches. The sound of the voices is accompanied by the thudding slap against the whiteboard of the yellow Mario hand on the tip of Tenzin S.’s plastic pointer.

On the way back to Manhattan, several of the students are waiting for the subway with their parents. Tenzin S. smiles and waves from across the tracks, but then says, “many parents not speaking Tibetan with their kids.” He says that it’s not enough for the children to come to the Sunday School – they have to also be immersed in Tibetan culture at home.

Dr. Jamspal, a professor of Tibetan Language at Columbia University also tells me that Tibetan children growing up in the U.S. are losing their native language. “The people like Tenzin S. and others volunteer to teach language, but once a week not enough.” He swivels slightly in chair in a classroom in the Religious Studies building at Columbia University. “Language is the root of all culture,” he says, looking over at his teaching assistant for approval. “Isn’t that right?” he asks her, nodding. “No language, no culture.”

His worries for the Tibetan culture aren’t limited to the U.S. He tells me that the official language of Tibet is now Chinese, and says that it’s very difficult to get a job in an office in Tibet unless you speak Chinese. “Dalai Lama is trying to get autonomy for Tibetan language,” he says. When he says autonomy, it sounds like autonoma .

It’s a cloudy Thursday in February and Diki Daycare is barely recognizable from the chaos of Sundays. The mood seems more formal; more strict. The carefree pell-mell of the traditional Day of Rest is non-existent. Instead, the occasional muffled murmur from behind closed doors of a teacher is the only sound. Little coats are hung on low hooks, mittens and scarves stuffed carelessly into the pockets, on the verge of falling onto the floor if jostled.

Inside, Diki is seated in front of a desktop computer. When Diki speaks, she always has a smile on her face, even when talking about difficult topics. “Tibetans are scared.” She’s referring to Tibetans in the U.S; the same, gentle smile still present.

In Tibet, she says, the culture isn’t reliable. What she means is that it’s quickly disappearing. She mentions that the daughter of one of her friends who lives in Tibet doesn’t even speak the language. To be admitted into an institution of higher education requires proficiency in Chinese, not Tibetan. In fact, the Tibetan language isn’t even taught in schools in the region after the fifth grade. This change has occurred as recently as January in some areas, making it difficult for students who have been instructed in Tibetan their entire lives to suddenly switch to Chinese.

She pauses as a grandmother who has come to pick up her granddaughter stops by to talk to her. Her voice carries a heavy Italian accent as she talks about her granddaughter’s aspirations to be a doctor. She speaks with her hands just as much as her words. Back in Italy, she says, her family was filled with doctors, so she knows it will come naturally to the little girl who’s not yet six.

Diki tells me that the Catch 22 of the Tibetan immigrant community is that unlike almost any other immigrant community in the U.S., Tibetans find even less of their culture in Tibet than they do in America. "Most people can rely on their culture when they go back to their country," she says. "But us, we can't, because our culture is disappearing."

Even in the monasteries the monks rarely use written Tibetan anymore. Dr. Jamspal speaks of a time, while he was still living in Tibet, when ancient Tibetan texts were studied very closely by the monks, requiring them to have a high level of proficiency in not simply modern Tibetan, but also in the ancient or “pure Tibetan.” But now, he continues, people in his hometown of Ladakh, near the border of India, mainly write either English or Hindi.

In the Sunday School, the children are taught everything from the language, to traditional Tibetan dance, to history. The language and dance components go smoothly. The history lessons are more of a challenge. Historical events that are considered by Tibetans to be very important are simply no longer taught in schools in Tibet. Other events that are still taught are often altered to promote China’s strength and show that Tibet was never an independent country.

This has been happening now for many years – even Tenzin S. mentioned that during his imprisonment, the history classes given to prisoners two to three days a week had a Chinese view of the way things occurred. “Before, Tibet very, very strong,” he says. “Tibetan have money, army from the British.” After the Chinese took possession of the area, everything changed. “Chinese leader say Tibetan mind not in present,” he says. “They say future bad for Tibetans.” Under the guise of helping the “under-developed” Tibetans enter into the modern day, the Chinese government has tried to force Tibetans to accept their changes. The region has also been permeated by large numbers of Han Chinese, who now control a large part of the business in Tibet.

There are records of Tibetan history available in India, but they’re all based on myths. “In India, every story starts with ‘And by the blessing of this God, this king came to serve the Tibet and the Tibetan people, and that king was the reincarnation of some God…” Diki says. She doesn’t want to mix Buddhism with history.

But the trickiest part in compiling and writing a textbook for the children at the Sunday School is the fact that the history lessons are being taught to Tibetan children growing up in the U.S. “The Tibetan children who come to the Sunday School, they were born here, so basically they’re American,” she continues. “What we are teaching is American-Tibetan.” She tells me that she finally decided to go with the Indian version, but will make significant changes. “That’s why I had to give it to Tenzin-la to pull out all the real history and leave out all the mythical parts,” she says, laughing.

Changing and adapting aspects of Tibetan history to make it relevant to the Tibetan-American children growing up here is just one part of the shifting culture. “For every generation that comes to the United States, there’s always a little bit of change,” Diki says. “We’re modernizing, we’re in contact with the outside world, we’re not in Tibet.” She pauses, then adds that she doesn’t think it’s possible for the current generation to keep the Tibetan culture as their parents do. “I don’t even think that their parents kept the culture the way their parents did either,” she says.

Basically, she explains, there are two kinds of families that come to the Tibetan school. “We have the really strong family that want their children to really learn and become 200 percent Tibetan,” she says. These are the ones who are concerned about the effects of American influences that their children are exposed to outside their homes.

“But then there’s another group of the family who is sending their kids here so they don’t feel guilty about not letting their kids learn Tibetan culture. And they don’t really care much after that.”

“Everything is changing,” Dr. Jamspal says. “Here in America, more clever, more efficient.” He is comparing the opportunities and education system here to that of the rural village of Ladakh in Tibet where he grew up. There, the spoken dialect was Ladakh, a pure and now seldom used version of Tibetan. “At school I did not have any paper. I used to write on the wall with the charcoal.” Textbooks came from the nearby monastery and were written in gold leaf. School wasn’t an option for everyone – it was generally reserved for the wealthy or those studying to become monks. As a young boy, Dr. Jamspal had to beg to be allowed to attend classes.

Here in New York, the dress is different, the food is different and the behavior is different in the Tibetan community, he says. But he doesn’t mean that this is a bad thing. In some instances, it is quite the opposite. Despite the loss of culture, both Diki and Dr. Jamspal emphasize the point that here in the U.S. they are able to keep the best aspects of their culture and eliminate the bad. "300 years ago, Tibet very different place, but now it changing," he says. "Everywhere changing. America changing."

As part of the Tibetan language classes, and in an effort to raise money for a trip to Tibet this summer, the children are learning to perform the play of Snow White. Diki says that it's nearly impossible to find a Tibetan play that she could use, and even if there were one, the children wouldn’t understand it from a cultural context because there is no new material being written in Tibet. “If I pull a Tibetan play, there is a lot of material I could use, but they wouldn’t understand it right away.” And besides, “Snow White motivates them to learn.”

This past summer Tenzin T. went on a trip. He traveled, along with his entire family, to hear the Dalai Lama speak in Washington D.C. When His Holiness comes to the United States, many Tibetans make the pilgrimage to hear his speeches for the entire duration of his stay. In the fall of 2010, Tenzin S. went to Toronto for two weeks and stayed with relatives to hear the Dalai Lama.

“In the beginning I was pretty excited, you know, go to D.C., see a new city, hear His Holiness speak,” Tenzin T. says in the cool, offhand tone of a teenager. “The first few days of speaking were interesting,” he begins, then stops. He glances furtively over his shoulder and looks around to see who else might be listening to our conversation. “But after two weeks it got kind of boring. I mean, it’s just speaking. For two weeks straight.”

“I get kind of confused sometimes,” Tensang says. Sometimes, when she’s doing her homework for her classes in public school, she writes her name and the date on the wrong side of the sheet of paper, instead writing it the way she’s been taught at Tibetan school. “My teachers will call me in, and say to me, ‘Tensang, what is this?’” She puts on a deep voice and points to an invisible piece of paper, waggling her finger, pretending to be a teacher. She giggles. “I guess Tibetan school has really influenced me. It sinks in.” Tensang considers herself to be first and foremost Tibetan. While she can’t pinpoint exactly why she feels this way, she just responds, “I just don’t do what Americans really do.” The other day at school, for example, she was playing with her friends and they started running ahead of her. Without thinking, in the heat of the moment, Tensang yelled out “ Gutha! ” which means “Wait up!” in Tibetan. “I think I’m normal, but sometimes I do things like that,” she laughs revealing her bright smile. “I guess I combine both Tibetan and American ways of living,” she shrugs. Her mom recently traveled to India and brought back books on Tibetan culture for Tensang to read. “So that was cool,” she says.

Dechen’s mom often goes to Jackson Heights to a video rental store to bring back movies for her daughter to watch. This particular store, Dechen says, in her deep, whispery voice, rents videos in Tibetan; namely Tom and Jerry cartoons. When I ask about these cartoons that Dechen watches, Diki quickly elaborates. “Yeah, it’s Tom and Jerry,” she says immediately, interrupting my rambling. These movies come directly from Tibet and have been adapted and translated using a classic dialect, rather than modern slang. “So, if you watch Tom and Jerry, you will learn a fluent, perfect Tibetan,” Diki says brightly, smiling at the irony of it all. Unfortunately, since 1999, the production of these videos has ceased, much to Diki’s disappointment, as she would find good use for the videos in her Sunday School.

“My family are always doing things to influence Tibetan culture,” Dechen says. She stops talking and her eyes dart in different directions behind her glasses. “Sometimes I feel like my culture is actually more of Tibetan than American.” Despite being from Nepal, Dechen didn’t know how to write in Tibetan before coming to Tibetan school. Now in her third year at the school, she says the writing is becoming easier.

“The Tibetan language is changing,” Dr. Jamspal says. “It becoming smaller.” Nowadays, even in Tibet, monks read much more than they write. “No need to write,” he says. He worries that one day soon, written Tibetan may be lost. As the language is evolving and changing, letters are being dropped off the end of words, some phrases are becoming outdated while others are out of use altogether. “I tell Tenzin S. to keep teaching those children how to write.” Dr. Jamspal notes that he has several nieces and nephews who were educated in India, and despite being able to speak Tibetan, they cannot write it. “Really not many people writing Tibetan anymore,” he says. To properly learn the language, he says that one must know Kangyur and Tengyur; Kangyur being the ancient texts of Buddha, and Tengyur being the Tibetan translation of these texts. The best way for the current generation to learn, he says, is to speak with their elders.

Each member of the older generation that I spoke with is worried that the current generation isn’t retaining the Tibetan culture in the way that they would like. Dr. Jamspal believes that whether the young Tibetan-Americans keep their roots is conditional, and depends on where they find themselves in life. “If they will have some difficulties, they will keep religion,” he says. “But if things not so difficult, they will forget,” he says, laughing with a heh-heh-heh sound. “You will have human nature, if we have some difficulty, then we are looking for some spiritual.”

For others, such as Tenzin S., who have endured the brutalities of the Chinese presence, passing down elements of the culture and teaching the young Tibetans growing up in the U.S. becomes a way of passing down knowledge and saving the Tibetan way of life from disappearing. Tenzin S. welcomes young Tibetans into his home, sits them down on the daybed that he uses as a couch, serves them milky tea, and helps them with their Tibetan language homework. During one of my visits, he even gave me two books on learning the Tibetan alphabet. “You practice, then next time we talk about it,” he tells me. Over the years he has also taught a handful of adult students; one woman without a drop of Tibetan in her blood was simply fascinated by the culture and found her way to Tenzin S. She became one of his most diligent students.

When he tells the story of his imprisonment, of being forced to do heavy, manual labor for 14 hours a day, of being beaten with metal rods, and of being forced to sleep on the hard, stone floor of a tiny prison cell with 18 other prisoners, he seems unfazed by the brutality of his experience. When he recounts how he and his fellow prisoners used to steal food from the horses when they weren’t given enough to eat, his eyes light up with a mischievous glint and he laughs before continuing. Though he does not talk directly about how harrowing this experience was, Tenzin S. is very active in raising awareness about the cultural genocide occurring in his homeland. In addition to teaching young Tibetans every Sunday, he has traveled to Washington D.C. to speak to Congress about the current situation in Tibet.

One day, Diki envisions expanding the daycare center into a public school. She wants to have a place where anyone can go and learn Tibetan five days a week, because even though the Tibetan children growing up here may attend the Sunday School, “they’re really American.”

“But I know it’s a long way away,” she says. “Every time His Holiness is here, he always requesting the Tibetan community to keep the Tibetan language and culture alive by speaking Tibetan,” Diki says. The Dalai Lama also asks Tibetan parents to do their part as well, by only speaking to their children in Tibetan. “The exile community is good at keeping up the culture. Here we are free to make our own community centers, to set up our own Tibetan school. In Tibet, that doesn’t exist.” The freedom that exists in the U.S. has enabled the community to freely practice their religion. There is no government telling them to denounce the Dalai Lama, there is no alteration of their history or snuffing out of their culture. Aspects of the culture have changed and continue to do so with each new generation, but ultimately they can shape their culture and practice their religion as they see fit. Here, they are able to create their ideal Tibet, away from the suffocating presence of an oppressive government.

And yet, the Tibetan community in New York is not without its struggles. “So many Tibetan parents, they having problems with their teenagers,” Diki says. “The teenagers are turning to drugs, and they’re not listening, just like regular American teenagers.” In Tibet, the common method of dealing with an unruly child is to use physical discipline. “The Tibetan parents don’t know about having a time out, or grounding their children. In Tibet they don’t even treat you as a human being until you’re 18 or 20,” she laughs. “Even my grandmother has a little hole in her right cheek that is from her teacher.” Her grandmother, it turns out, didn’t do her homework properly, so the teacher; and here Diki pauses, asking her assistant in a blur of Tibetan the name of the instrument used as punishment. “He used a very sharp thing on her cheeks.” Her grandmother’s parents brought many gifts and gave words of thanks to the teacher for disciplining the young girl.

Such strict punishment is now no longer practiced in Tibet, but Diki says that light physical discipline such as spanking is still very common. “There is a saying, in Tibetan, that children’s ears are in their butts,” she says. Diki hopes to put together a workshop for the parents to attend on how to discipline their children in the ‘American way.’

As the interview is wrapping up, Diki suddenly starts talking in a low, quieter voice, leaning in toward me. “It’s so hard here, for Tibetan people, all of a sudden you’re expected to follow all of the rules and the husbands beat their wife back in Tibet and they’re no longer allowed to do that here, and everything is a shock to everybody.” She says that the husband of one family that used to attend the daycare is currently in jail for beating his wife.

The freedom of growing up in America is allowing the current generation of Tibetan children to explore their culture in a way that their peers in Tibet are unable to do. They're learning a history of their parents' homeland that hasn't been altered to accomplish the agenda of a repressive government. They can choose their own identity and can practice their culture and religion as much or as little as they please. The Tibetan community and culture that exists in the U.S. is theirs to shape. Tibetan school provides them with further insight into their roots. Its influence, combined with that of their parents, no doubt plays a large part in the interest of the current generation in their heritage and religion. But they are ultimately the ones who will decide whether to one day pass down the traditions that they learn each Sunday. At this point they are eager to learn about their ancestry and want to help their fellow Tibetans. They are proud when they talk about their culture and it’s clear that they feel a deep connection with the region and culture of their parents.

At the same time, going to public school in a city like New York means that they have friends from all over the world. One of Tensang's best friends is African; another is Chinese. Talk of Halloween and Hollywood movies flow easily. When the Tibetan children reach the point where there is nothing more for them to be taught at Sunday School, will their interest in maintaining their heritage still be as strong? Will they want to carry the heavy load of Tibet's problems or will the homogenization of American culture pull them instead? As the culture continues to disappear in Tibet, it is the generation of young Tibetan-Americans who have not only the ability, but the responsibility in the eyes of the elder generation, of keeping it from being lost.

“My mom always tells me, you can’t forget where your blood is from,” Tensang says.