Becca Genne-Bacon showed me her garden on a cold November morning, a day when a layer of frost was covering most of the city. In the warmth of a Union Square coffee shop, she lifted her shirt just enough to reveal a glimpse of a green leaf below the edge of her blouse. It gave way to twelve flawless flowers inked onto her abdomen–a perfectly preserved spring in the dead of winter. Two yellow daffodils, two purple pansies, four primroses in varying shades of indigo, two oriental lilies with smatterings of fuchsia freckles, and two roses, a shy pink bloom peeking out from behind the bouquet and one blood red blossom dominating the front.

Genne-Bacon got her flower piece when she was eighteen, but she didn't stop there. Three years later, she not only has seven tattoos of her own, but is now completing her final year at New York's School of Visual Arts, where she is learning how to ink them onto others.

In the age of television series like Miami Ink and heavily tatted celebrities like Angelina Jolie and Lil Wayne, the growing popularity of body art has helped tattooing evolve from what once seemed like work for the down-and-out into a viable, perhaps even glamorous, occupation. As the industry expands into both the fine art and commercial worlds, doctors and district attorneys have joined the drunks and drug addicts in tattooing their bodies to signify important junctures in their lives, mark their individuality, or simply to own a piece of art that is not so easily stolen or lost. From the street to the workplace to the walls of a Chelsea gallery, ink is flowing fast into the mainstream.

Click to enlarge

A tattoo from sketch to finish, done by Josh Payne of Artfuel, Inc. (Source: Josh Payne)

A 2006 Pew survey found that forty percent of Americans between the ages of twenty-six and forty admit to having at least one piece of body art. The Wall Street Journal suggests that upper middle-class women between the ages of twenty and forty comprise most of the growth. Yet in 2008, a study published in the Journal of American College Health found that undergraduates at a New Jersey college perceived people with tattoos more negatively than they did those without them. Similar research conducted by Viren Swami and Adrian Furnham in 2008 showed that tattooed females were rated "less physically attractive, more sexually promiscuous and heavier drinkers" than their unmarked peers.

Despite the seven tattoos scattered all over Genne-Bacon's body, those negative stereotypes do not apply to her. The daughter of a schoolteacher father and a social worker mother, Genne-Bacon grew up in the suburbs of Flemington, New Jersey. A pretty brunette with long wavy hair and a cute button nose, she got her flower piece to cover up a large scar left behind by a series of abdominal surgeries, an idea gleaned from an article she read about a burn victim who chose to accentuate her scars by tattooing an outline around them. Genne-Bacon admired the girl's effort to seem beautiful not despite her scar but because of it. "If people stare at my stomach," Genne-Bacon said, "in my head, they're staring at my beautiful flowers and not my scar." Although her mother was dubious at first, she has come around to liking Genne-Bacon's flowers but still has issues with the small shark inked on her daughter's left calf and the little pig on her left foot and the rooster on her right. The pig and rooster totems were once popular among sailors because they were thought to protect the wearer from drowning.

Studies conducted from the 1970s to the late 1990s perpetuated the negative stereotypes still so often attached to people with tattoos. Most of these studies focused on the body art of prisoners, gang members and the mentally challenged, associating the tattoo with risky behavior, aggressiveness and mental disorder. However, more recent studies, such as the one conducted by the Canadian tattoo scholar Michael Atkinson, suggest "a giant schism between social scientific interpretations of tattooing and contemporary sensibilities about the act."

As part of his research, Atkinson spent three years observing tattoo artists and their clients in Calgary and Toronto. The ethnographic data he collected suggests that tattooing is now a routine way of expressing one's identity or marking social position. Clinton Sanders of the University of Connecticut, a pioneer in the field of tattoo sociology with more than twenty years of experience, corroborates Atkinson's findings. "While there are some crazy people getting tattooed," he said, "it is not a pathological phenomenon."

In Sanders's book, Customizing the Body, he observes that the spread of tattoo consumption has "decreased its power to symbolize rebellion." "It's hard to have something that is stigmatizing when a third of Americans have that thing," he told me. "It's sort of like being stigmatized by having a Chevrolet."

Several researchers whose studies suggest there is a lingering stigma attached to tattoos acknowledge Sanders's point. Swami and Furnham, who studied tattooed females, found an interesting anomaly in their results. Although a majority of the study's participants admitted to having negative views of women with tattoos, more than two-thirds of the same group paradoxically said that they would consider getting a tattoo themselves. David Wiseman, who co-authored the study with New Jersey college undergraduates, agrees that attitudes toward body art are changing. "I think that tattoos would be shown to harm perceptions to a much greater degree had my studies been done ten to fifteen years ago," he said.

Jason June of the Brooklyn shop Three Kings Tattoo, offered a simple explanation. "Everyone is getting tattoos now, so it doesn't segregate you into any sort of social sect," he said. "I think that idea of tattoos is slowly going away." Josh Payne agrees. He works out of Artfuel Inc., a tattoo shop in Wilmington, North Carolina. "I tattoo every walk of life, from your scumbag, dirtbag–and those are still out there–to doctors and lawyers," he said. "There is no norm anymore in terms of tattooed people."

Tattooist Stephano Alcantara of Last Rites Tattoo Theatre in New York City grinned as he recalled a surprising client he met on a tattoo tour in South Dakota some time back. "I did a tattoo on an eighty-four-year-old girl, I mean, lady," he said, making a small circle with his hands to estimate the size of the flower he inked onto her skin. "She came into the shop and was so optimistic about getting tattoos, saying, 'I'm a little late, but I'm just starting!'"

Whatever Alcantara's client's reason for delaying, legal impediments would have also been a factor fifty years ago. For much of the latter half of the twentieth century, many states outlawed tattooing. In fact, the last state to legalize tattooing was South Carolina in 2006. Tattoo legislation is usually regulated at a municipal level, however, and in many U.S. cities it is still illegal to set up a tattoo shop. Due to a local outbreak of blood-borne hepatitis, in the 1960s, New York City prohibited tattoo shops; the ban wasn't lifted until 1997. One of the largest victories for tattoo legislation was won in September of 2010, when a California federal court overthrew a Hermosa Beach ban on tattoo parlors. The court decision described tattooing as a "purely expressive activity fully protected by the First Amendment," and was the first instance where doing and getting body art were successfully tied legally to Constitutional rights.

However, the holdouts remain. Recently, the Palatine Village Council in Illinois voted down a proposal to open a local tattoo shop, saying that "tattoo parlors carry a stigma." But across the United States, shops continue to pop up. In March of this year, the Hanover Planning Board in Massachusetts approved a permit to open an upscale "tattoo salon" in the town mall between a Dunkin' Donuts and a Subway sandwich shop. If tattoo businesses continue along this path, getting tattooed at your local mall may soon be as common as getting your ears pierced at Claire's.

"The prevalence of tattoos in mainstream culture has opened up a new territory of people who would not have considered it before," explained Dr. Mary Kosut, an assistant professor of Media, Society and the Arts at Purchase College, which is part of the State University of New York school system. "The negative cultural stereotypes are now taken away because tattoos are more accepted."

Among those in this new territory is Ross Hammond, who grew up in a small town of three thousand in suburban Maine, where the only people he ever saw with tattoos were the truck drivers passing through. But in 2009, when he was eighteen, Hammond's older sister Whitney died suddenly in a car accident. As a result, Hammond became clinically depressed. He was receiving treatment in a hospital when he came across a poem in a book that his sister had given him. It was called "The Bare Arms of Trees," by John Tagliabue, and it gave him an idea.

I think of immovable whiteness and lean coldness and fear

And the terrible longing between people stretched apart as these

branches

And the cold space between

The poem goes on to describe how with spring and the "play of leaves," the branches would touch again. To Hammond, Tagliabue's tree signified a journey he hoped to make–from the desolation of his family's mourning to their ability to celebrate his sister's life. His father helped him sketch an image of the tree and he worked with a tattoo artist to refine it.

Hammond pushed up the sleeve of his plaid shirt to show me the result. A wizened tree stretched across the underside of his right forearm, its twisted trunk extending downward to his wrist, bearing dark branches that curled outward in heavily tattooed lines on his skin. The branches were bare, save for two tiny red leaves clinging desperately to the tips of the boughs, as if buffeted by a strong wind. Hammond explained that he first planned on getting a tree covered in foliage. "It is the leaves that make the tree a good thing," he said. "But then I thought it should be bare, because at the time I felt that it should be."

The tree remained naked for almost a year, until Hammond decided to add a new leaf annually on Whitney's birthday to commemorate both her death and her life. He smiled as he described the yearly event, when his family comes together–he from New York, his parents from Maine, and his older brother from England–to celebrate his sister. "Getting my tattoo definitely helped me through," Hammond said, tracing his fingers over the tree's empty branches. Describing how he would eventually progress from getting red leaves to getting green ones, he likened the tree's transition to his own process of moving on. "The first year the tree was bare and I thought about what that meant," he said. "In a few years, it will be different. It will be back alive."

Hammond, Genne-Bacon, and Alcantara's eighty-four-year-old client are only a few examples of the ever-expanding tattooed community. But as tattooed individuals become part of the general population–studies suggest that as many as fourteen to thirty-five percent of adolescents and young adults in the Western world are now tattooed–how apparent is body art becoming in the workplace?

In the more creative industries, the answer seems to be "very." Take Angelina Jolie's most recent Vogue cover. Standing with her back to the camera and peering coyly at the lens from over her shoulder, Jolie doesn't grab your attention like she usually does–with her trademark full lips or plunging décolletage. Instead, your eyes are drawn to the large tattoo inked in Gothic lettering on the nape of her neck, and the five lines of Cambodian script just visible over her left shoulder. Despite Jolie having appeared on three previous Vogue covers, this is the only one where any of her tattoos show, no mean feat considering that she has at least a dozen. Vogue's editing decision was the official stamp of approval on the tattoo trend that has been sweeping the modeling world, where body art is no longer just something to airbrush out.

"Remember the Calvin Klein guy with the big panther on his stomach?" Barrett Pall, a model and aspiring actor, asked me, referring to the iconic underwear ads that featured the Swedish soccer player, Fredrik Ljungberg. In the ad, Ljungberg poses in white boxer briefs, unadorned save for a large panther tattoo above his right hip bone. "They took him because of that panther," Pall said. "It worked for him." In fact, Ljungberg's tattoo was also digitally enhanced, moved from its actual place on his back to the more prominent spot on his hip.

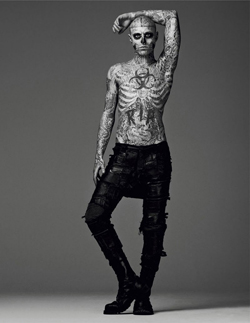

The modeling world is now rife with body art, with catwalk regulars like Heidi Klum and Kate Moss all sporting visible tattoos. Just this fall, the high fashion label Thierry Mugler chose Rick Genest, once homeless and living in Montreal, as the new face of the brand. Genest is tattooed entirely from his waist to the top of his head. Much of his ink works like an x-ray would, depicting the bones that lie under his skin, thus Genest's nickname, "Zombie Boy." Discovered by Mugler's creative director Nicola Formichetti, Genest walked in the Mugler show

Barrett Pall himself has two tattoos. Mars (french for March, his birth month) is scrawled across his ankle, a piece inspired by the time Pall spent studying abroad in Paris. His second tattoo, the word "Imagine" stamped on the right side of his lower back, reflects his love for the music of John Lennon, a passion Pall shares with his mother, who chose the placement of the piece. The tattoo is inked on the same spot Mattel stamps its brand on its iconic Barbies. The comparison is apt. With his blond hair, blue eyes and chiseled jaw, Pall could be a real-life Ken doll. Now a modeling veteran at twenty-two, he says that both pieces have been included in his photographs multiple times. "They like seeing your individual self and what's cool to you," he said of the casting directors and bookings editors who choose him for jobs. "You're cast not just on how you look, but how you style yourself."

Click to enlarge

Rick Genest modeling for the Thierry Mugler Autumn/Winter 2011/12 Men's Collection, shot by Mariano Vivanco (Source)

Style also helped Michael Ronan clinch an internship at a music magazine. Handed a checklist of interests to choose from, one of the options the New York University senior picked was "tattoos." Seeing his choice, his interviewers then asked if he had any. "I was wearing a shirt where you couldn't see them," Ronan remembered. "So I took it off and they were like, 'WOW.' But I got the job."

"Wow" is a common reaction to Ronan's tattoos. He has about a thousand dollars and fourteen hours worth of ink depicting a grim reaper and a large phoenix, along with a few smaller images, streaming down from his shoulder caps. "All the places I've worked have had people with visible tattoos," Ronan said, listing coworkers at Spin magazine and at a financial firm where he did I.T. work.

While body art can convey style and individuality, it can also suggest strength. In Samoa, where tattooing existed long before the Europeans set foot on the island in the 1700s, getting tattooed is considered a mark of manhood. "To the Samoan man, it is a crucial event in a lifetime, from which all other happenings are dated," wrote Frances Flaherty, who in 1925 traveled with her husband, Robert, a documentary filmmaker, to the island to film the ritual. "Until he is tattooed, no matter how old he may be, the Samoan man is still considered and treated as a boy." Flaherty suggested that this belief stemmed from the idea of "a common human need, the need for struggle and for some test of endurance, some supreme mark of individual worth and proof of the quality of the man . . . tattooing stands for valor and courage and all those qualities in which a man takes pride." In fact, as the anthropologist Augustin Kramer observed in 1903, if a Samoan man tried to avoid the tattoo ritual, he was immediately shunned as a social pariah who "no father would accept . . . as a mate for his daughter." Both Flaherty's and Kramer's experiences appear in Steve Gilbert's comprehensive Tattoo History Source Book.

Perhaps this historical viewpoint can explain the preponderance of tattoos among professional athletes, in whose field body art has none of its usual taboos. Celebrated sports figures like David Beckham and Kobe Bryant cover most of their bodies in tattoos and also enjoy multi-million dollar endorsement deals. Every time Beckham gets a new piece, he generates a frenzy of media coverage speculating on the possible meanings of the ink. The 2003 book, In the Paint: Tattoos of the NBA and the Stories Behind Them, suggests that up to seventy percent of the National Basketball Association's players are tattooed and an ESPN review of the book observed that "body art dominates the NBA, and for many players, their number of tattoos is higher than their nightly scoring average."

Dr. Mary Kosut, the tattoo scholar who teaches at Purchase, noted that even in her own profession, tattoos are becoming more accepted. "There are some colleges where tattooed professors are a good little mascot," she said. Explaining how Purchase uses body art on its webpage to depict the college as more hip or fashionable, she said, "There are students that they carefully brand themselves for. There are students on some of our [web] pages with full sleeves. Now tattoos are being used as this obvious marker of cool or alternative."

However, she acknowledges that this might not be the case in all industries. "Some people definitely have to go undercover with their tattoos," she said. "You might be disadvantaged if you work at Morgan Stanley, or as a lawyer, or in other more conservative professions. I think that tattoos are going to be read pretty negatively within those contexts."

As someone in such an industry, Stephanie Chung has had mixed experiences. Chung worked her way through high school and college at a law firm, where at one point she had eight tattoos, bright pink hair, and twenty-two piercings. "It was frowned upon by certain people," she said. "But to others, who already knew me and knew that I did a good job, it didn't matter what I looked like." However, she admitted that this could have largely been because she had an administrative role without much client interaction.

Indeed, in many businesses in the service industry, such as at McDonald's and Starbucks, official dress codes still explicitly prohibit employees from displaying visible body art. Chung has three visible tattoos, two on the insides of her upper arms and one on her ankle. "I personally don't think anything more would have been acceptable. I wouldn't have gotten the job here," she said, referring to her current position at Citigroup as an undergraduate recruiter for the bank's internship programs.

After graduating from college, Chung took out her piercings and dyed her pink hair back to black, covering her tattoos when she went for interviews. After four years at Citi, she now feels comfortable enough to occasionally go without a jacket at work, exposing her two visible arm tattoos. When she wears a skirt or dress, her ankle tattoo can also be seen. "Once you get to where you want to be and you show that you do your job well, you can be yourself a bit more," she said. "But coming in, you have to play the game. It's unfortunate, but people will judge you for what you have on your body. As much as that sucks, I don't want to sacrifice moving forward in my career just because I have tattoos."

As a recruiter, when Chung visits campuses or does presentations, she makes sure to wear a sweater or suit jacket. "There's just this stigma around people with tattoos and it's really funny that I would put them in that box as well," she said. "I think it's just what is ingrained in us by society – that we should be a certain way in our suits."

Chung isn't the only one who still feels this way. A 2007 survey conducted by the career information website Vault.com found that although forty-four percent of managers have tattoos or piercings other than in their ears, forty-two percent of that group would still have a lower opinion of an employee with visible body art. Seventy-six percent of all participating managers thought that visible tattoos were unprofessional. "Having tattoos is a normal thing to do," Chung explained. "But it's also normal to know that we can't expose them in a corporate environment."

Analia Alonso, Morgan Stanley's head of corporate campus recruiting, had a similar response. Undergraduate job candidates at Morgan Stanley go through several rounds of interviews in a process similar to those of many other large financial institutions. "You could have an interviewer with a very liberal mindset who doesn't think twice about someone who comes in with a tattoo," Alonso said. "But you might have another interviewer who is more conservative and doesn't think it is appropriate. I think your best bet is still to cover it up."

Even tattoo artists are mindful of the corporate mindset. "Tattooing hasn't got so far that the same person with the same résumé who doesn't have a skull over their throat isn't going to get hired over you," said Timothy Boor, a tattoo artist working with Alcantara at Last Rites. "If you're covered in horrible artwork, it shows your self-respect level [and] your decision-making skills."

Josh Payne of Artfuel added, "It's not just what I perceive but what the public still perceives." "Even in my profession, knowing that it really means nothing, I'd be hesitant purely for the fact that the person is a representative of my business, and what everybody else is going to perceive [is] based on that."

But based on the progress so far, Barrett Pall, the model, foresees a future where full acceptance of body ink spreads beyond the creative industries. "We were told by our parents, "You can't go to work and have a tattoo," he said. "But now our generation in general has tattoos. In the future, we're all going to be sitting in the same boardroom with tattoos."

Pall's vision seems a logical progression of the large strides made by the tattoo industry in the last hundred years, as tattooing moves increasingly away from commercial "street-level" work to the more advanced level of fine art. While there have always been recognized artists in the field, such as Samuel O'Reilly and Don Ed Hardy, for much of the twentieth century, the majority operated out of shops that offered a few hundred standard pre-drawn designs, known in the industry as "flash," in only a handful of hues. Most of these would be boldly colored in reds and blacks, with heavy outlines, a style now classified as Traditional American. While there were a handful of good artists at the time, Last Rite's Timothy Boor said, "everyone else was kind of home-job, [doing] prison art with little machines that they made out of car parts."

In an essay entitled "A Trip Down Memory Lane," George L. "Doc" Webb, a prominent tattooist in the mid-1900s, remembers such a time. Most tattoo shops were located in Navy towns, as sailors represented a large percentage of the clientele. This was mostly for practical reasons. Seamen were employed year-round and paid more frequently than other military men–twice a month instead of once. Loggers and construction workers lost their income in the winter, so they too were unreliable customers. Thus, tattoo shops were most common in port towns, and were often confined to the local "Skid Row," next to the "burlesque houses, the fifteen-cent theatres, the nickel arcades," and the brothels. "We were all classed alike," Webb wrote, "the dregs at the bottom of the barrel."

In the 1930s, Webb continued, most flash pieces ranged in price from twenty-five to seventy-five cents. The bulk of the artist's income came from twenty-five cent pieces that clients chose from a large-sized "pork-chop sheet," so named because the money it brought in allowed the tattooist the luxury of buying pork chops instead of hamburger meat. Besides the pork-chop sheet, most tattoo parlors only offered five or six other sheets of flash. Tattoos only came in two colors then, red and black, although green was later added. Brown became available after World War II.

After the war, however, escalating rental prices led to higher prices for body art, too."Instead of large pieces for five dollars, small pieces were going for twenty dollars," Webb observed. "Tattooing had changed. The client had changed."

Since Webb wrote those words, the tattoo clientele has continued to change. No longer are tattoo studios relegated to the slums - the Hanover Mall, with its Macy's and MacDonald's, is quite the upgrade from the grittier company Webb's shops used to keep. These shops also attract a much more diverse group of patrons than their 1930s counterparts. In fact, most branches of the military have now enacted strict body art regulations. In the Navy, tattoos cannot be placed on the head or neck, and cannot be visible through the seaman's white uniform. Any body art on the lower arm must be no larger than the wearer's fist. And even though a sailor can obtain a waiver for pre-existing pieces, naval commanders can recommend removal or even military discharge if the former is not feasible.

Body art removal is another aspect of the industry that has made large advances in the last few years. Tattoo ink is no longer as indelible as it once was; new laser techniques can now help fade away the ill-conceived ex-girlfriend tattoo inked on your upper arm. A few years back, the only places people could get such treatment was from dermatologists, many of whom didn't know much about tattoos and simply zapped away general areas. Now, many tattoo shops employ in-house technicians who can laser very specific parts of the body, a preferable option for those who only want one section of their full sleeve washed off. And in his book Customizing the Body, Clinton Sanders wrote about a new tattoo pigment, Freedom-2, that may be removed with just one treatment (after as many as five treatments, tinges of most tattoos can still be seen on the skin.) These new innovations, Sanders wrote, "require somewhat less commitment on the part of tattooees."

But some argue that this lesser commitment can also be dangerous. "You should at least have the mindset that a tattoo is a timeline of your life," Timothy Boor said. Looking down at his first tattoo, a small tribal design on his wrist, he laughed at its silliness. "But when I see it, I remember my twenty-one-ness and I didn't give a shit and wanted my tattoo on my wrist and I have no desire to cover it up," he said. "At the minimum, you should at least have that."

Instead, Boor advocates that tattooists emphasize technique, considering not only the style of a piece, but also how it will age over time. He described a detailed painting he was going to ink on a client and explained how he was trying to convince him to make it bigger so that the detail would endure. Jason June also stressed the importance of technical skill. "Your solid colors should balance with enough contrast to bring them forward - if you don't have those things, they will fade out over time," he said. "Solid ink and the proper application. [Otherwise] even if the picture looks great, its not going to stay in."

Boor's and June's technical expertise reflect another industry change: the mainstream embrace of tattoo as an art form has attracted a slew of talented new artists, many with professional training. And they are hardly confined to Doc Webb's red, black, green and brown, but have a full spectrum of colors to work with, opening the way to new styles such as full-color portraiture, photorealism, and what is known as biomechanical

Boor began his artistic career as a graphic designer for Chrysler. In 2007, about the time he turned thirty, Boor was doing a part-time tattoo apprenticeship when the recession gave him the opportunity to take a buy-out that came with a fifty thousand dollar check. Boor used the money as a cushion to throw himself into tattooing. He now works out of New York tattoo shop Last Rites Tattoo Theatre, owned by famous tattooist Paul Booth. Boor likens his work to that of commissioned painters in the old world. Citing artistic influences like Da Vinci and Caravaggio, he explained, "Back in the day, all the artists I like were pretty much commissioned artists for the Pope, and he went to their art studios with what he wanted to hang in his home and they did it. That's how tattoo shops are now, in a way."

Today, high-end tattooists can command hundreds of dollars an hour for their work. Doc Webb wrote that in the 1930s, a large chest piece cost seven dollars and fifty cents. Last year, my own tattoo, a thin line of script spanning about three inches, set me back one hundred dollars. Thus it is not surprising that an increasing number of people have begun to see tattooing as an aspirational occupation rather than the fallback it usually was in the past. Becca Genne-Bacon graduates in May 2011 with a degree in illustration from the School of Visual Arts. "I think there is a difference between tattooists and tattoo artists," she said. "There are a lot of people who can work a machine and trace a stencil, but there are also a lot of people right now, especially in New York, who are amazing fine artists. I want to be a tattoo artist, and that's why I'm paying thirty grand a year [for tuition]."

Click to enlarge

Timothy Boor proves that tattooists are artists too with this tribute to Caravaggio's Medusa inked onto a client's balled fist. (Source: Timothy Boor)

Three Kings's Jason June took a grittier route to a career in fine-art tattooing by seeking out what he described as some "colorful" people from whom to learn the craft. That was fifteen years ago, in 1995. "[They] would tattoo whomever as long as you could buy your own equipment and you could pay them in beer or in pot or whatever," he said. "It was pretty raw, pretty fucking sketchy–you kind of had to know somebody to get a tattoo and it was really more dangerous."

Like Boor, June now mostly does custom work for a number of recurring clients out of Three Kings, but he remembers that things weren't always so comfortable. "We did whatever we could to make ends meet," he said, citing stints working warehouse jobs and at Best Buy. "You kind of did [tattooing] on your own until it became profitable enough for you to live off of."

June said that it is only in the last couple of years that he has had experience working directly with people from "extreme art backgrounds," referring to those artists who have had professional art training before deciding to pick up a tattoo machine. "It's amazing to see the things those people can bring to the table," he said. But he also acknowledged some friction between "old-school" artists and this new breed. "Sometimes [other artists] hate on people who come from a cushier background like that – there's a huge tradition of grit and grime [in the industry]," he said. "It is important not to get threatened by it but to actually look and see what the good things are that those people bring to the table. In a history of assholes, a couple of nice kids are not the worst things that could happen."

And as skilled artists join the industry, the fine art world has begun to take notice. June recalls a popular 2010 summer show held at Manhattan's PJS gallery in Chelsea, where six tattoo artists were invited to display some of their artwork. "We were told 'Here's a space – just fill it,'" he remembered. "'Have a good time with it and do whatever you want.'" The result was Metanoia, named for the Greek word for the reforming of one's mind. Featuring the work of top tattooists like Thomas Hooper and Chris O'Donnell, the show included drawings, paintings, and sculpture, much of it tattoo-inspired.

Paul Booth's Last Rites Tattoo Theatre has a permanent gallery space, which I visited one afternoon in March. Located in Manhattan's Hell's Kitchen, the gallery caters to the darker side of artists' imaginations, and my own imagination was running wild as I waited for the slow-moving service elevator to cart me up to the third floor. It felt like a trip up the Tower of Terror in the Twilight Zone. Luckily instead of a drop, the doors opened and I pushed through a second door into the Tattoo Theatre.

My first thought was, So this is why they picked Hell's Kitchen. Everything was dark and painted in black and red and I half-expected something to jump at me from the shadows. Paintings of skulls and ghouls and fantastic monsters that only appear in nightmares hung from the wall. The haunting opening notes of Gothic metal band Lacuna Coil's "Heaven's a Lie" floated ominously through the darkness. But then the hallway opened into the tattoo studio, a large square room with high ceilings decorated in a Gothic style, where the three house artists–Boor, Alcantara, and their colleague Toxyc–sat at three pristine work stations. They were professional and friendly and as I greeted them, my anxiety slowly dissipated.

Any lingering hesitation evaporated when I walked toward the art gallery section. Connected by a single walkway, the darkness of the studio gave way to bright lights, stark white walls, and giant oil paintings of brilliant flowers and luminous pearls draped over two-foot skulls. It was beautiful with a touch of the macabre. And at the end of the room, I found Paola Duran, the soft-spoken gallery assistant from Colombia whose giggle could put anyone at ease.

"It used to be from my point of view like it was from another world, or even tacky or tasteless, before I worked here," Duran said of tattoo art. "Now I see it in an artistic way." She described recent shows and famous artists who the gallery has hosted, pausing to introduce me to Fred Harper, an artist whose illustrations appear frequently in The Week magazine, as well as in the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and Time. After a bit of coaxing from Duran, Harper, who has shown repeatedly at Last Rites, obligingly rolled up his shirtsleeve to reveal a stunning black and grey portrait done by Paul Booth that ran down the entire length of his arm.

To illustrate how the fine art world has begun to embrace the notion of tattoo as art, Duran described a routine show opening at Last Rites. "All the people from the tattoo world and the gallery people, and you mix them together," she said, gesturing in large circles to show the scale of the events. "You have the director of the National Arts Club, this very posh guy, next to the motorcycle guy with the tattoos. They mix well."

Until it happened, Boor never never thought he would find entrance into the world of fine art through his way with a tattoo machine. "It seems a little backward," he said, showing me a Caravaggio that he was going to replicate on a British client flying in especially to have Boor do the job. "But Paul [Booth] has sold paintings for thousands upon thousands of dollars."

Most major museums still favor a real Caravaggio over the work of a tattoo artist but many smaller, edgier galleries are beginning to showcase the work tattooists do on canvas, not on skin. "I think, in certain contexts it can be framed under the rubric of art, but the contexts have to be typically either ethnographic or historical, like at the Museum of Natural History or under the category of folk art," Dr. Kosut suggested. "But there hasn't been a museum show or a 'sanctioned' gallery that has taken on tattoo art as a legitimate art form with a capital 'A.' And the reason is: What do you show? A body?"

Boor advanced the thought. "There is no question that the tattooist is an artist; there is no question that the art is art," he said. "But there's that fine line of displaying it and buying it. You can't buy someone's back." After a pause, though, he brought up the medical museum at Tokyo University, where a collection of thirty tattooed human skins are available for viewing to a private audience, mostly comprised of visiting doctors. "That one guy crossed the line in a big way with the Bodies exhibit," Boor said, "If that's fine and legal for me to donate my body and for it to end up being artwork, why can't it be with tattoos?"

The art cognoscenti may still be grappling with how to define and display tattoo as art, but the public has been quicker to embrace the notion. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than at a tattoo convention, where people congregate to pay hundreds or even thousands of dollars to get tattooed by their favorite artists. Since their inception in the 1970s, there are now more than fifty conventions annually in the United States alone.

As I walked though the glass sliding doors into the lobby of the Sheraton Philadelphia City Center Hotel, I heard it immediately. A thick, incessant high-pitched buzz that managed to drown out the loud rock music playing over the speakers, as if I had just walked into a hive swarming with a hundred angry bees. The sound was a hundred tattoo needles buzzing away at once, all weekend long at the Philadelphia Tattoo Arts Convention in February.

Two hundred and twenty-five booths were packed into approximately ten aisles, representing more than one hundred different shops from all over the country and the world. The artists came from Texas, New York, Michigan, Florida, and even South Korea, a country where tattooing is still technically illegal. There was a veritable army of chairs and massage tables set up, one or two for every shop, and as I walked down the aisle, I saw a woman to my left balancing on a table while getting her calf inked with a bright tangle of roses. To my right, an artist leaned over a young man, tattooing the top of his head as he tapped away on his BlackBerry, as casually as he would in a chair at the barbershop. Three feet away, a girl tilted her neck to receive a small butterfly. Everywhere sleeves were pushed back and pant legs rolled up, the endless buzz the only obvious difference between this and getting your face painted at the state fair.

This was clearly an artistic community–people greeted each other like old friends, some having met at other conventions. Many came to get tattoos from specific artists and they recognized each other's ink like art students picking out the Monets from the Pissaros. Most artists talked shop, comparing tattoos and techniques, but they also inquired about each other's families and how life was going on up there in New Hampshire. Artists were doing custom sketching and many also had paintings or drawings for sale, ranging from life-like renderings of bucks and bears to the bold Traditional American pin-up girls. Their résumés were as varied as their portfolios–apprentices sat next to artists who had been tattooing for decades. But even more striking was the size and diversity of the crowd.

Looking at the number of people packing the aisles, it was hard to imagine that tattoo has ever been seen as a counter-cultural phenomenon. The air was punctuated with "Excuse me's" as people jostled to watch the tattooing or flip through the portfolios on display. The crowd was mostly young, in their twenties and thirties; most were heavily inked and many had multiple piercings. My fist twitched involuntarily as I imagined fitting it through the gauges in the ears of the man standing two booths down from me. I faced a sea of Mohawks, fishnets, combat boots, and black eyeliner. Punks love tattoos. But then there was the father calmly pushing his daughter in a pink stroller, stopping occasionally to let her point out pictures she liked. There were a few curious teenagers flipping through portfolios and a grandmother perched on the edge of a chair to watch her grandson go under the needle.

Tattoo artists attribute this broad acceptance in part to the mainstream media's embrace of tattoo culture, for which they are largely grateful. "Before, it was a very secretive thing, tattooing," said Artfuel's Josh Payne, who traveled to the convention from North Carolina. "You didn't go and get a tattoo knowing about it. It was scary and weird. So it's cool that it's out there and people know about it and what to expect."

Jason June agreed that the entertainment industry's depictions of the lives of talented tattoo artists has both made the field attractive to many others and has educated the public in the ways of the craft."We wouldn't have people in here painting stuff and putting it on people just because they're good artists as much if [the entertainment industry] hadn't put those shows on," he said, nor would clients be walking into shops for the first time as knowledgeable as they have become over the past five years, sometimes even allowing the artist the freedom to choose the image himself, with minimal direction from the client. Becca Genne-Bacon said she never brings many pictures when she gets a new piece. "When I got my iris [tattoo], I went and said, 'I want an iris on my arm and I want something pretty traditional,' that's it," she said.

In 2005, TLC began broadcasting Miami Ink, the hit reality TV show set in a Florida tattoo shop. Now in its fourth season, the show's runaway popularity led to two spin-offs, LA Ink and London Ink, and the network is scheduled to launch NY Ink in June 2011. The franchise also spawned several copycat shows, like A&E's Inked and Spike's Inkmasters, a competitive tattooing show set to premier this summer.

Like many other artists, Boor says that the biggest problem he has with television's portrayal of the tattoo world is its propensity to perpetuate the industry's negative stereotypes. "It's like any other reality show–it has nothing to do with what the show is actually supposed to be about," he said. "I've seen tattoo shows where they're just taking shots and smoking in the shop. I'm not trying to be a priest and say I would never drink, but there is a professionalism that that kills. The average nice shop takes itself seriously; you're not just sitting there tattooing with a cigarette sticking out of your mouth."

More controversial than its move to reality TV was the debut of tattoos on children's programming. In late 2008, Sesame Street aired a segment featuring Nebraskan indie pop group Tilly and the Wall, in which one of the band members, Kianna Alarid, sang the alphabet while dancing in a sleeveless day-glo dress, her full sleeves of tattoos on display. Sesame Street later uploaded the video to YouTube, where it garnered more than four million views and set off a heated debate in Youtube's comments section about whether showing body art on a children's program was appropriate. One of the more popular comments, posted by user aaronldaley, read, "You must lead an awfully sheltered life if you think tattoos and wheelchairs are strange… what colour [sic] is the sky in your world." The post garnered 49 "likes" from other YouTube users.

USA Today, which has the second highest national circulation after the Wall Street Journal, runs a weekly online feature entitled "Tattoo Tuesday," in which readers are encouraged to submit pictures of their body art. And the advertising world has jumped on the bandwagon as well. In 2010, Pilot Extrafine pens launched a series of print advertisements in which Pilot pens were used to draw intricate tattoos onto six Lego figurines to demonstrate the fineness of Pilot's pen nibs. In the same year, Yahoo! ran an ad featuring a young woman with her two arms fully covered in tattoos of popular social networking logos with the tagline, "Your own personal everything." Ford Motors, citing research findings that forty percent of Millennials (those born between 1980 and 1995) and thirty-two percent of Gen X-ers have body art, recently announced a line of vinyl decals for the 2012 Ford Focus, marketed as "tattoos" for your car. A Ford news release quotes the brand's manager, KC Dallia saying, "Millennials have a very personalized, artistic side to their lifestyle, and their vehicle is a very important part of that."

But while most tattooists are grateful for the business that such campaigns have brought into their shops, at times the onslaught of tattoo marketing can seem a bit too much. "It kind of sucks to hear that [the tattoo industry] has gotten bigger than us," Jason June said. "Over years of being independent businessmen and subcontractors and being in control of our own world, essentially, it's hard to say now that this one thing that we've created is now too big for us."

"The counter-cultural value of being tattooed has certainly changed as it has become a marketed element of popular culture," Clinton Sanders, the tattoo expert, added. "It takes it away from the folk art element that I find very appealing… it's right up there with interior decorating and that does move it away from the gritty, appealing historical elements."

There is also the worry among those in the tattoo world that as body art moves away from its darker historical roots, it will be diluted into just another passing fad. Many artists and tattoo experts, for example, respect the work of tattooists such as Norman "Sailor Jerry" Collins or Don Ed Hardy , but they also lament the blanket popularity of their eponymous clothing lines, now thrust into infamy on shows like MTV's Jersey Shore. "Now that [tattoo culture] is more popular and its been adopted into the mainstream, there are other parts of it that seem a bit more commercial, too mass..." Dr. Mary Kosut said, trailing off. Taking a breath, she continued, "I will say this. It makes me cringe when I go into the bar and I see Sailor Jerry signs or sneakers and Ed Hardy t-shirts."

Click to enlarge

Pilot Extrafine Pen inked tattoos onto Lego figurines to demonstrate the fineness of the Pilot pen nib. (Source: Ads of the World)

Sanders is more concerned with the transitory nature of the fads themselves. "It is the nature of popular culture, that it runs in cycles," he said. "As things become much more popular, people get tired of them, in the same way people are tired of reality programming or Harry Potter."

Josh Payne expressed a similar thought. "[Tattoo] is now going in the other direction of being bad – it's getting too popular. And that's almost worse," he said. "The next generation will be a very un-tattooed generation. Think about it. Why did people our age get them? Because it was a rebellious thing. We were trying to defy what our parents wanted. Well, you always want to grow up different than your parents. When we are all heavily-tattooed people, the younger ones are going to go the other way."

If Sanders and Payne are right, it wouldn't be the first time that the tattoo has fallen quickly into and out of public favor. In Customizing the Body, Sanders mentioned a 1897 article in the New York Herald that asked its readers, "Have you had your monogram inscribed on your arm? Is your shoulder blade embellished with your crest? No? Then, gracious madame and gentle sir, you cannot be au courant with society's very latest fad." Yet by the early twentieth century, Sanders noted, the popularity of body art had begun to flag and tattoo became increasingly associated with much more unsavory characters than the aristocrats who had borne them previously.

Despite that history, however, many artists and tattoo enthusiasts maintain that tattoo culture, like the ink itself, will not be so easily eradicated. "For the people who are just getting a tribal armband right now, that's definitely a trend," Becca Genne-Bacon suggested. "They'll get over it. But for people getting the big tattoos, full sleeves and body suits and back pieces, that's obviously not a trend for them. They're not spending thousands of dollars and undergoing painful work just to be cool."

Boor said he thinks the tattoo trend is an indelible one. "I don't think it'll ever go away," he said. "There may be swells–ups and downs–in the mainstream world, but [tattoos] have been popular since they began." To illustrate his point, he refers to Ötzi the Iceman, Europe's oldest natural human mummy, who was found to have fifty-seven tattoos, mostly simple short lines and markings.

To Jason June, the enduring appeal of the tattoo is more basic than that, tied to an inherent characteristic of the human body. "[The body] is really the only thing you can ever hope to own in life and you can now alter it," he said. "And that expression and appreciation for your own form, that's something that I hope to pass on to my kids."

Jill can be contacted at