The Curwin girls, ages ten, eight and six, move between French and English the way their figure skates glide over ice. Their parents have to stand outside the rink. Roxanne Mendoza, their mother, understands about half of what they say when they talk among themselves or with their French-speaking nanny, one of several the Curwins have employed over the years. Their father, Gary Curwin, is left out entirely. He understands not a word, "pas un mot," as the girls like to say.

Children from families like the Curwins make up one third of the student body, grades pre-kindergarten to twelfth, of the Lycée Français, falling into the enrollment category of "U.S. Citizens." Another third of the students have French citizenship and the last third have dual French-American citizenship. In Manhattan, the two other private, French-English schools with consistent bilingual instruction beyond the preschool level have comparable demographics. Parent interest in all three schools is high.

This passion for studying French is not limited to those who can afford an annual tuition of around twenty-five thousand dollars. At public schools in four of New York's five boroughs, advocacy groups have helped institute dual language programs in French in elementary schools, where Spanish programs are much more prevalent. And in addition to the Lycée Français, the Lyceum Kennedy and L'Ecole Internationale de New York, there are five other private elementary and preschools in New York City that cater to French families and those who seek French culture. Three of these have opened just in the past five years. Why and why now? For the three hundred thousand New Yorkers with a French connection, it is, as it has always been, primarily an effort to preserve their cultural and linguistic bonds. Those sans French background see bilingual education as aspirational, a way to gain what they see as important cultural capital for their families.

Yet this renaissance of enthusiasm for bilingual French-English education stops at exit 31 on Interstate 495. Outside of Manhattan and its sister boroughs, budget cuts within the past couple of years have led four Long Island public school districts to remove French instruction at the middle school level; at least two more plan to phase out the language next year. The trend reaches beyond the borders of the state of New York, affecting public schools in districts managing budget cuts throughout the United States.

What makes New York stand out in the renewed interest in Francophilia appears to be a combination of the relatively large number of French or Francophone nationals who live in the city permanently or temporarily, and the affinity of many New Yorkers for French language and society. As immigrants from France move to this cultural mecca, American residents latch onto the history and culture they bring with them. The French value what many New Yorkers do--the arts, fine food and intellectual pursuits--and the language's pleasing sound lends it an air of sophistication that some feel English lacks. To a certain New York set, French equals chic.

On a Wednesday morning in February, Leo, who is three years old, took a black beret from a box of dress-up clothes, plopped it on his head and posed proudly. Sophie joined him, grabbing other mismatched articles of clothing from the plastic bin against the wall, deciding who would be who in the area of the large room marked off with blue tape for imaginative play. Leo turned away from the bin to lift a doll from its cradle. "Petit bébé," he said as he handed the doll to Sophie, giggling, perhaps at his brief inclusion of French in their game. They exchanged other three-year-old thoughts in English and were interrupted only briefly when one of the French teachers walked through the play area from the back room.

"Je suis le papa de Sophie!" Leo declared.

"Mais, non!" the teacher replied in mock horror.

Leo attends Le Petit Paradis, a Montessori preschool on the Upper East Side of Manhattan that offers instruction in French and English. Its name is French for "little paradise" and the school is small. Made up of just two rooms, the preschool has had full enrollment since opening day three years ago, when a large group of Manhattan parents, including Madonna, chose it for their toddlers' bilingual instruction. Here, two classes of fifteen students each speak French and English throughout the day with one French- and one English-speaking teacher.

As the children play in the safari-themed room, they switch between languages as comfortably as they would their favorite toys, effortlessly responding in French to the French teachers and in English to the American ones. As for the students, there are a few giveaways as to what their first language might be. I hear one native Francophone child, Elsa, command her growing tower of wooden blocks, "Ça va pas tomber! Ça va pas tomber! Ça va pas tomber!"

Leo is what Christina Houri, the school's founder, would call an international student. His parents speak five languages between them. His Chinese mother, Elaine Hsu-Sanchez is conversant in English, Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese and a little Spanish. Her Latin American husband is fluent in English and Spanish. They have imparted three of these languages to their two children, Leo and his older sister, Lina. The children, though, speak a total of four languages in varying degrees of fluency: English, Spanish, Mandarin and French.

Still in his first year at Le Petit Paradis, Leo picked up French after only a few months. When he started at the bilingual preschool, he understood Mandarin and some English. He had Chinese nannies, not French ones. Now he has no trouble telling Sophie he will play the dad and his French teacher that he is indeed Sophie's papa.

Houri, who speaks six languages herself, estimates that about eighty percent of the students at Le Petit Paradis come from French families, ten percent from international families and ten percent from American families. She would like to see this last group grow. "There is such a limited percentage [of Americans] that really are keen on languages," she said. "It's not because America has all the states that are speaking one language that we should not have children learn more languages, so hopefully that mentality will change."

Although the percentage of American families at Houri's school is small, this number would have been smaller almost thirty years ago when Le Jardin à L'Ouest first opened for Manhattan's French-speaking families. In 1972, Dominique Bordereaux-Hiigli and her husband, John Hiigli, began a nursery program for two- to five-year-olds in their duplex apartment on the Upper West Side. The school opened officially in 1975, and since then has provided childcare and education to some thirty students at a time, exclusively in French. "We were the only school for many, many years and of course this decade everything seems to have changed," Bordereaux-Hiigli said.

Le Jardin à L'Ouest was, in the beginning, more of a daycare center than a structured preschool. Today, its five-person staff prepares children for kindergarten with half-day programs that focus on art as well as the French language. And the school has just begun to acquire company, at least in the French aspect of its program. In recent years, Bordereaux-Hiigli has offered advice to educators wishing to start a preschool like hers. Houri, once a student teacher at Le Jardin à L'Ouest, was one such educator.

Yves Rivaud, founder of L'Ecole Internationale de New York, also became involved with bilingual French education at another New York school. He used to be the head of Lyceum Kennedy, a French American school in midtown. In its third year, L'Ecole Internationale de New York is a more recent addition to the schools that start French education in pre-school. When Rivaud decided to open L'Ecole Internationale de New York in the Gramercy area of Manhattan in September 2009, he felt certain he would fill the spots for students from the nursery school level to fifth grade. "We decided to [create] this school because so far you have only two French schools in Manhattan and knowing that you have eight million people in Manhattan, we definitely need a third school," he said, adding that the spots for the youngest students are highest in demand.

Parents understand that the earlier children take on a new language, the easier it will be for them to become and remain bilingual. Houri, a strong believer in the benefits of early bilingualism, gives prospective parents a list of ten reasons to choose bilingual education over more traditional options, including possible benefits to brain development and later academic progress. She believes that children tend to be more creative, have stronger analytical skills and are much more likely to speak their second languages as well as native speakers. Houri points out in her list that this combination makes it easier for bilingual children who attend French preschools to gain acceptance to prestigious elementary schools, like the Lycée Français. "Otherwise," she said, "the way the American system is going it's too late. It's just, unfortunately, a lot of kids will learn [languages] when the brain is just not absorbing as much as earlier on."

A 2001 study titled "Bilingualism in Development: Language, Literacy and Cognition" by Ellen Bialystok, a professor of psychology at York University, reports that early bilingualism benefits cognitive development but does not necessarily make children smarter. While children who become bilingual during preschool are able to better "selectively attend to relevant information," they may have smaller vocabularies in one or the other language than monolingual preschoolers. Hsu-Sanchez, though, says that her children are able to speak multiple languages without issue.

Though Leo and Lina might not yet be able to make use of all four of the languages they are able to speak and comprehend, their parents see their multilingualism as beneficial to their cultural and cognitive development. "It's like taking piano lessons," Hsu-Sanchez said. "You don't necessarily want to make sure your children become pianists but it's working a different part of the brain." It would be easier, though, for Hsu-Sanchez's children to stick to the languages their parents already speak fluently, begging the question, "Pourquoi le Français?"

Actually, there is a logical reason for Lina to have started speaking French. She began learning the language at the preschool she attended when the family was living in Paris. When they moved to New York, her parents thought it best to continue with her French instruction. At age four, but just for a year, she attended Le Petit Paradis the first year it opened. Lina, now six, does not attend the Lycée Français, and this is a bit unusual for having attended a preschool Houri describes as a "feeder" for the bilingual elementary and high school. Instead she attends P.S. 6, a highly regarded public school that only offers foreign language instruction in Spanish and Mandarin during classes after school. This doesn't mean that Lina has stopped speaking French. With a French tutor, she spends two-and-a-half hours twice a week in French conversation and play.

Her brother will likely follow the same course. "I think it would be a major decision if we were going to put them on the French path," Hsu-Sanchez said. "So we decided a few years of French when they are young and then we'll continue to hire tutors and babysitters to speak French." To Hsu-Sanchez, French is no less important than any of the other languages her children speak. "French, we like it because it's very beautiful and very difficult to learn and so we see them using it for really a kind of personal cultivation and to open their minds to different cultures," she said.

The Curwins' mother, Roxanne Mendoza, was also attracted to French for its beauty. And like Hsu-Sanchez, she is familiar with the need for a French nanny in a non-French-speaking household. When her first daughter, Bridget, was eight months old, her mother enrolled her in a French class at the Language Workshop for Children. During one of these classes, Mendoza heard another child with an American mother speaking beautiful unaccented French. She was moved to ask how this was possible. The girl's mother told her that she had a French-speaking nanny.

To Mendoza, the idea seemed like a good one. When Mia, her second child, was born, the family's nanny had just left and Mendoza began the search for one who spoke French. Bridget was two-and-a-half years old and Mia was about six months old when the first French nanny came to work for them. Speaking French was also a requirement for the occasional evening babysitter. By the time Ashley came along a year later, the set up for the youngest daughter's eventual bilingualism was in place. For eight to ten hours a day, someone was speaking in French to the Curwin girls.

Any questions as to whether the hours of French exposure were working towards the girls' fluency were answered for Mendoza when she noticed Ashley talking in her sleep. Her words were neither English nor the nonsensical sounds of sleep-speech. The Curwins' youngest daughter was dreaming in French.

A casual search on the Childcare section of Craigslist brings up almost seventy postings from people either seeking French nannies or from nannies advertising their French fluency. These nannies likely have their pick of employer. This was the case with Sarah Gray's nanny. Gray posted an advertisement on Craigslist requesting a part-time French-speaking nanny to care for her one-year-old son, Hagan. She asked that the applicants reply by email in both English and French. About seven or eight people responded but she knew as soon as she saw Melinda Ramos's e-mail that she didn't want to interview anyone else. Ramos is a French-speaking native of Paris who can "just ramble on in French without thinking about it," a requirement for Gray, who does not speak French but has always regretted not attending a French school while growing up in Sarnia, a small city in Southwestern Ontario.

Luckily for Gray and her son, Ramos accepted the part-time job although she already had a position with another family—a French one. From this other employer, Gray was happy to learn that unlike many French nannies in the city, hers speaks proper French, devoid of slang or incorrect grammar. The French mother also told Gray that it's not easy to find a well-educated French nanny for young, French-speaking city children.

The insistence that nannies be native speakers seems to be universal, whether the family speaks French or not. One post I came across on Craigslist specifically requested a "TRUE French governess." But there is one major downside to hiring exclusively native French speakers as nannies and babysitters: their visas expire and they go home. This is a problem Hsu-Sanchez has encountered. Although she prefers sitters from Paris for their accents, she recently settled on a woman from Luxembourg, acceptable because she attended a French school. "It's difficult," Hsu-Sanchez said, "because they usually finish their studies and go back."

Mendoza has had more than ten nannies over the past eight years, but hiring new nannies to supplement the French her daughters hear in school at the Lycée seems a necessary inconvenience. She wants Bridget, Mia and Ashley to speak as beautifully as their nannies do, with all of the idiomatic expressions and turns of phrase that will mark them as truly bilingual.

Mendoza was never fluent in French, though she studied it for four years beginning in middle school. Her French teacher was not French, but American. While Mendoza was her student, the teacher took a trip to Paris. When she returned, she expressed to her students her astonishment at the speed with which the French people spoke. "We were all thinking, 'You're the French teacher though, I mean, wasn't it easy for you?'" When Mendoza realized that not even her French teacher was adept at speaking French, continuing to study the language seemed a bit futile. Unlike her children, she did not have what she describes as the "infrastructure" to help her master the language.

Mendoza said she is most drawn to French for the way it sounds, but the reasons for French's long-held position as the second most taught language in the United States likely go deeper than its mellifluousness. French was the lingua franca of the educated class in Europe from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries—a status achieved as a result of France's widespread cultural and diplomatic influence during the rule of Louis XIV. In the twentieth century, the strength of the British Empire coupled with American dominance caused English to begin to supplant French as the language of international commerce. This may have also led to our country's predominantly monolingual ideology when compared to educational language policies of other first world nations. But in recent years this has started to change, at least in metropolitan areas.

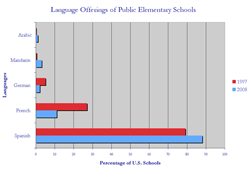

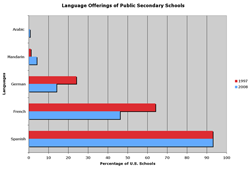

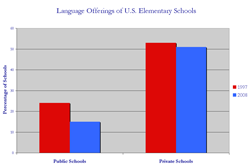

In the United States, most students who study any foreign language do not begin to do so before the age of fourteen and, as indicated in a 2008 study by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), the number of students below high school level who study foreign languages has decreased over the years. From 1997 to 2008 there was a noticeable decline in foreign language education in public elementary and middle schools. While foreign language education held steady in private schools, schools in rural areas and schools with students of lower socioeconomic status had increasingly limited access to language instruction. The disparity is significant. Private elementary schools are actually three times more likely to offer language classes than public schools at the same grade levels. Public schools that must rely on state budgets for programming are apt to cut languages. French, like art and music, is often seen as expendable.

During the eleven-year-period between these two studies, not all languages were taught less frequently in American schools. Arabic and Mandarin, for instance, were offered more at both the elementary and secondary school levels in 2008 than in 1997. The number of Spanish classes at the elementary level also increased. French, however, was not among the languages to gain in popularity. In fact, French instruction decreased by sixteen percent at the elementary level and by almost twenty percent at the secondary level in that same period.

Although French no longer has primary status as the world's language, it continues to be one of the most common studied in schools. That, however, seems to be changing. In New York State, budget cuts have forced school administrators to make choices-- they see that fewer students enroll in French classes than in Spanish classes, so French instruction becomes more vulnerable to the cut. That is what happened on Long Island, where districts in both Nassau and Suffolk counties have phased out French in middle schools.

Madeline Turan, vice-president of the American Association of Teachers of French, taught French and Spanish on Long Island for years and is now active in foreign language planning in the area. She said the issue is complex. "There are so many things chipping away at language education in this state," she said. Budget cuts coupled with the popularity of Spanish and, more recently, Mandarin are the chisels chipping away at Rodin's native language.

Chinese has become a very popular choice at New York schools in recent years. Even in the bilingual English-French private schools, particularly Lycée Français and L'Ecole Internationale de New York, Mandarin is introduced in the third grade. Some administrators see Mandarin as emerging as the new English in international commerce. The New York Times City Room blog has highlighted New York City's former schools chancellor Cathleen Black's commitment to placing Mandarin language programs in public schools.

Mandarin may seem to be more useful than French to the modern, business-minded parent but, as Turan pointed out, it is also much more difficult to learn. She said languages such as French and Spanish are level one languages, while Mandarin is a level four language, meaning it takes four times as long to gain proficiency. However, Mandarin has become increasingly present in schools, at least in New York State, partly because of advocacy on the part of the Chinese government. "I believe that there's a strong interest in Chinese and money out there for districts to offer Chinese," Turan said. "The Chinese government has made a phenomenal amount of funds available to adopt Mandarin and for people to go to China, to take advantage of trips to China where they can see the language in action."

As Mandarin's usefulness abroad is just becoming apparent, parents have long been aware of the utility of Spanish in America as well as overseas. Higher enrollment in Spanish classes solidifies its place in public schools despite budget cuts that put learning a second language on the low end of priority lists. The dwindling support for French, comparatively, is evident in the College Board's 2009 decision to cut the Advanced Placement French Literature exam. (The Spanish equivalent still exists). But although you'd be hard pressed to find a public school that does not offer Spanish instruction beginning in middle school, you would be harder pressed to find a bilingual Spanish-English private school. In Manhattan, at least, French has this distinction.

Turan feels that "suburban attitudes" are partly to blame for the contrast between the presence of French within Manhattan and its absence outside the borough. "[In Manhattan] they see more French," she said. "There's more out there so it's more living than what we have here." Some people just don't see how useful French can be. The language, more than others once of equal popularity, requires advocacy. When French is threatened, parents need to prove its worth to school administrations.

A bit before two on a Monday afternoon in February, shouting children filled the concrete yard adjacent to the building currently home to P.S. 133. Just five minutes later recess was over and they were back inside the large brick building on the corner of Eighth Street and Fourth Avenue in Park Slope, Brooklyn. Inside, the hallways were quiet, though the presence of children was evident in the bright colors of student artwork covering the walls. A female security guard seated at a folding table at the front of the hallway directed me to the offices where a second woman told me that the principal was in a meeting and would just be a moment.

As I waited, three women in the outer section of the principal's office went about their work while listening to the soft sounds of an R&B radio station. I was reminded of the public elementary school I attended in Philadelphia. The women working at their desks seemed in a way familiar, and when the principal's meeting ended, two girls that could have been my classmates at age nine or ten exited the office. But this New York City public school isn't typical. Beginning in September 2011, P.S. 133, or William A. Butler, will introduce a dual language French-English program.

The French government has begun its own counteroffensive to keep French going in the public schools of America. The French Embassy's Education Attaché, Fabrice Jaumont, has teamed up with a consortium of Francophile organizations, including the French-American Cultural Exchange, the Florence Gould Foundation, the Grand Marnier Foundation, the Alfred & Jane Ross Foundation, Education Française à New York, or EFNY, and Friends of New York French-American Bilingual and Multicultural Education, Inc.. Together, they have helped establish programs in schools in Manhattan, Queens, the Bronx and Brooklyn. P.S. 133 will become the seventh local public elementary school to offer a dual language program in French.

The principal of P.S. 133 is Heather Foster-Mann, who hopes her own five-year-old son will be bilingual but in Spanish and English, not French. She herself does not speak French. The proposal for a French program at P.S. 133 came from a local parent with a son in pre-K, a Swiss father who wanted the school in his district to offer what some other public schools did. "He said, 'Before I sign on the dotted line and say I'm coming to your school, what else do you have to offer—Here's my idea," Foster-Mann explained. In May, the parent brought Foster-Mann a long list of other parents interested in having their children speak French in school. This made Foster-Mann aware for the first time of the large, local Francophone population in the district. She soon found out that French-speaking families weren't the only ones eager for French instruction for their children.

Although the official bilingual program has not yet begun, the school is gearing up for the changes. In October, EFNY, a group of parents that hopes to develop bilingual programs in New York's public schools, partnered with P.S. 133 on Thursdays after school to sponsor classes in French for both French-speaking and English-speaking children from the school or beyond. On Fridays, the same instructor who teaches French to the two playgroups also volunteers her time to teach French to the kindergartners.

Initially, Foster-Mann thought she would be "begging for kids" from American families to join the after school playgroup, but she ended up having to cap the class at about fifteen students, upsetting parents whose children did not make the cut. Now during application time for the new bilingual program, Foster-Mann gets almost daily emails from both Francophone and American parents expressing interest.

When I told Foster-Mann that I speak French, she jokingly asked if I had any interest in teaching. "I'm trying to recruit people," she said. The teacher she is hoping to recruit for September will teach a kindergarten class of twenty-four—twelve Francophone children and twelve native English-speakers. Half of the day the students will be taught in English and half the day they will follow the standard New York State public school curriculum in French.

In its first year, this one class will make up the bilingual program, but Foster-Mann hopes to see the number of participating students increase in time. "It's my dream that it'll grow our school in a whole other direction," she said. Ideally, she would start with two classes next year, but the Eighth Street and Fourth Avenue location is temporary, as the school's original building is undergoing renovation. When P.S. 133 moves back to its permanent home at Butler Street and Fourth Avenue, more of its two hundred forty students will be able to take part in the program, which will serve students in kindergarten through fifth grade.

Foster-Mann believes that it will take only three things to make this dual language program work: support from parents, a great teacher and support from the administration. The parental support has been in place since May and was further solidified with the involvement of EFNY. Foster-Mann will worry more about finding a qualified teacher this summer, as most teachers don't begin to look for teaching posts until June. As to the last of her requirements, Foster-Mann has got that covered. But it does take a bit more than a supportive attitude to get a bilingual program started.

The new class will also need two sets of books—one set in English and one in French for all subjects and two sets of general school supplies in two different colors, such as markers, tape and bins, so that the eyes of young children can easily distinguish between languages. Luckily, schools like P.S. 133 can find some funding for this. The French Embassy gives five thousand dollars to public schools starting bilingual programs in French, which Foster-Mann said will likely go toward furnishing two libraries in the two different languages. The school is also applying for a Dual Language Grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Any funds from this planning grant will support professional development for teachers.

What has helped to make possible the future bilingual program at P.S. 133 and public school programs like it, however, is parental encouragement. Foster-Mann had considered introducing a bilingual Spanish program to the school but said she just didn't get the "buy in." Parents in her district want French. "Parents and kids are really at the heart of these programs, you know, so it's really a partnership," Foster-Mann said. "It's not going to work if you don't have parents supporting it. So I work for parents, I work for kids. You know, whatever you want—within reason."

The six French dual language programs currently in place in New York City public schools are evidence of a trend of which certain New York City families have already been able to take advantage. From early on, the Curwins latched on to the idea that their American children would follow a French educational path. Another Lycée parent, Caroline Schleifer, made the decision in a more impromptu way. Her daughter Liliane was not even two when she applied for her to attend the pre-K section of the Lycée Français at the insistence of a friend who said it was time to think about schools.

Though Schleifer's mother is French, she grew up hearing the language more than speaking it and realized when she began studying French in seventh grade that she did not have a proper grasp of the grammar. Schleifer sang to Liliane in French, stocked shelves with French CDs and books and when the child was nine months old, she began taking her to a French class at the Language Workshop for Children. But Schleifer hadn't thought much about formal bilingual education. She describes the decision to send her daughter to a French school as "a little bit last minute" and though Liliane has some French in her background, the link to the country is such that her mother likens her family's French connection to that of families like the Curwins.

Liliane just started becoming fluent this year. "What is 'gaining fluency?'" she asked when I asked her mother about her French progress. In French, Schleifer told her daughter that it means that if Liliane were placed in the middle of Paris alone she'd be able to get around just fine. The seven-year-old gave her mother a dubious look and shook her head. This probably had more to do with the prospect of being left alone in Paris, though. Liliane seemed to understand the language perfectly.

At the Lycée Français, children who are not French learn not only the language but a French curriculum. Liliane understands currency in terms of the Euro, not the dollar, and when I asked her about the units she measures in, it took her a moment to answer. "Centimetres et...," she said and trailed off, and then translated, "Centimeters and..."

"Inches," her mother finished for her. Liliane confirmed that this is the word she couldn't find in either language.As her mother and I spoke in their Upper East Side apartment, Liliane flipped through a book, occasionally interjecting to ask the definition of a word or to add to her mother's responses. She gave her homework, splayed out on the carpet, just a mild amount of attention. All of her focus shifted to her schoolwork, however, when Schleifer brought up her handwriting. "Have you seen any of [the Lycée students'] homework?" she asked me. "It never fails to amaze me that they write like this compared to a second grader from any other school."

At the Lycée, students complete their work in cursive, as is done in elementary schools in France. Liliane actually has trouble writing in print (she gets her N's and H's mixed up) and the homework she showed me is filled with lines of neat cursive on the gridded pages typical of French cahiers. Schleifer, who has lived all her life in the United States, admitted that she could never, and still can't, write like that. Liliane offered proudly, "I can write like that!" In the mood to show me more things she can do, she began to play the piano.

The Lycée Français prides itself on combining the best of both American and French cultures and educational systems. The school website states that the Lycée's curriculum parallels that promoted by the French Ministry of National Education while incorporating the most important elements of U.S. private school education, making for "a sound combination superior to either alternative."

The Lycée Français de New York was established in 1935 by Charles de Ferry de Fontnouvelle, the Consul General of France in New York. It had strong support from both French nationals and Americans, excited by the prospect of a secondary school comparable to the best high schools in France. At the time, just twenty-four students attended three classes in the French Institute's building, now the French Institute Alliance Française. But by the 1970s, the Lycée had more than a thousand students and had acquired its own space. Since its opening, close to thirty thousand students of more than an estimated one hundred and fifty nationalities have opted to study at the school.

Around the time the Lycée Français was gaining prestige and students, the Lyceum opened in 1964 with similar goals, but with a commitment to following New York State regent standards, ensuring an easy transition to an American school. Though initially established for French families, today more than half the children enrolled in pre-K through fifth grade did not speak French before attending the school, while a third of the student population speaks a language other than French or English at home.

L'Ecole Internationale de New York joined the other two private bilingual schools in September 2009, filling three floors above French chef Laurent Tourondel's BLT restaurant near Gramercy Park. The school has just one class per grade level of sixteen to eighteen students. Rivaud described it as "family sized" and as such, it has the ability to provide personalized attention to students, such as speech therapy to help children struggling with one or the other language. Now, the school is at about seventy percent capacity but Rivaud believes it will reach full capacity by the 2011-2012 academic year. He is open to the idea of expansion. "Well voila," he said, as we toured the three floors. "This is our small school who wants to become big."

Rivaud thinks his school's bilingual education model may well help that happen. The students at l'Ecole Internationale de New York spend forty percent of their time learning in English and the other sixty percent in French. Rivaud said the French parents are enthusiastic about the English aspect of the program while the American parents are very pleased to have their children learn French. " The French program has kind of a prestige. It's very academic," he said. "And when it's combined with English and the American program it just fuses the two languages and the two cultures in a very efficient way."

The tuition at these bilingual schools ranges from twenty four thousand six hundred dollars, for one year at L'Ecole Internationale de New York to twenty five thousand two hundred thirty dollars, the cost of the final year at Lyceum Kennedy (the tuition changes year to year, at its lowest in first grade at nineteen thousand six hundred thirty dollars). These prices are less expensive than most Manhattan private schools, where tuition can reach well over thirty five thousand dollars by the senior year.

American parents who send their children to these schools are not only paying for a New York City private school education but also for integration into another culture. "It's amazing how fast the child is able to integrate the language and listen to the teachers," Rivaud said. "For some of them so fast, so fast it's absolutely amazing." But this would not be possible, he said, without strong support at home.

"Oiseaux," French for bird, was Bridget Curwin's first word. Since she began taking classes at the Language Workshop for Children, her mother has purchased French books and DVDs and of course has hired French nannies. When Bridget was about five years old, she attended an American school, having been denied acceptance to the Lycée Français. The Lycée, where her younger sisters were in the "petite section," recommended that Mendoza teach her to read in French. "It was definitely harder," she said of teaching her daughter to read in a foreign language. If Mendoza hadn't given Bridget consistent support and the tools to learn, attaining fluency would have been almost impossible, but she was committed to having her daughters "really own the language." After learning to read, Bridget left the American school she was attending to enroll in second grade mid-year at the Lycée.

When she signed up for classes at the Language Workshop for Children, Mendoza didn't know how involved with French her children would end up becoming. But when it came time to enroll in schools, she "got closer to the idea that they really had to go to [the Lycée Français] to really, have a really deep knowledge of the language." Now the three girls no longer need their mother to read to them. Not only that, but they provide Mendoza with the definitions of French words and correct her when she makes a French grammatical mistake.

Schleifer, already fluent in French, has always been able to help her daughter with her homework. Liliane's father, like the Curwin girls' father, cannot. Schleifer said he only gets excluded once in a while, but Liliane corrected her. "Every once in a while when I do my homework which is every day," she said. "That's not once in a while."

Families such as the Curwins, Shleifers, and the Sanchezes are the kind of parents who make bilingual education in New York thrive. "They travel a lot, they're more into the globalization aspect of life and they're more educated and cultured," Houri said. They also can afford it.

But as bilingualism is made more available to parents—parents willing to advocate for its inclusion in their local public schools—the question, "why French?" is ever-present. Mendoza admits that Spanish would be more practical. Though her father is Spanish, she never learned to speak the language, finding French so much prettier. She added that her girls, since being old enough to choose a language for themselves, have expressed interest in learning Spanish. Schleifer said Liliane also wants to learn Spanish because many of her friends from school speak the language at home.

But as Rivaud said, these committed families "have been touched by the French language" in one way or another, helped by New York's receptivity. "New Yorkers are very much in tune with French culture, French good taste of French food, of French language," Rivaud said.

It is a very particular segment of the non-French, New York population that can act on a love of all things French because, at the moment, French, more than other languages requires advocacy. In New York, its diminishing presence in public schools enforces French's status as an elite language— available to the children of families who happen to fall within a district with a newly instituted dual language program or to those who can afford to commit to private schools and nannies.

Mendoza could provide these things for her children. Now they speak the beautiful, "prestigious" language that seemed inaccessible when she was just a few years older than her ten-year-old, Bridget. For Bridget, Mia and Ashley, French is not only a language spoken in school, but a language in which to discuss movies, share secrets and, for at least one of the girls, a language attached to a culture included in fantasies of the future. Eight-year-old Mia likes to say she will attend the Sorbonne, marry a Frenchman and live in France. Her mother will be allowed to join her though. After all, learning French was maman's idea.

Monica can be contacted at